When the Bronx Was Burning

As a child accompanying my father to funerals in the 1970s, I witnessed the death of the borough’s Jewish community, one person at a time

On many a Sunday when I was a child, I accompanied my father not to baseball games but to funerals. A rabbi, he officiated at these deathly occasions near and far, but mostly in the Bronx.

This was the 1970s, and the Bronx—specifically the Jewish Bronx—was dying out. Those who remained in the West Bronx off the Grand Concourse had seen their children flee to the suburbs, where they made grand bargains to become “Americans” by giving up the collective identity they once shared through religious observance. They were artists and long-haired musicians, sculptors and playwrights with blonde women at their sides. Even as a boy, I understood that these folks had much more mischief under their belts than the law allowed. Yet in death and bereavement they returned to the Bronx and were, if not quite Jewish angels clothed in lily white, at least faithful to tradition.

These funerals were multilayered, funerals within funerals. Not only were they a swan song for the deceased and the bereaved—they were a final goodbye to the Bronx itself.

***

The Bronx was mythologized in my father’s countless retellings: When he grew up there, it was home to a quarter million Jews, to De Witt Clinton High School, to the Hebrew Institute of University Heights where 1,500 people came on the High Holidays to hear the WWII artillery gunner-hero Cantor Abe Veroba, to the live-chicken markets and endless kosher butchers, and of course, to stickball games that were as long as summer itself.

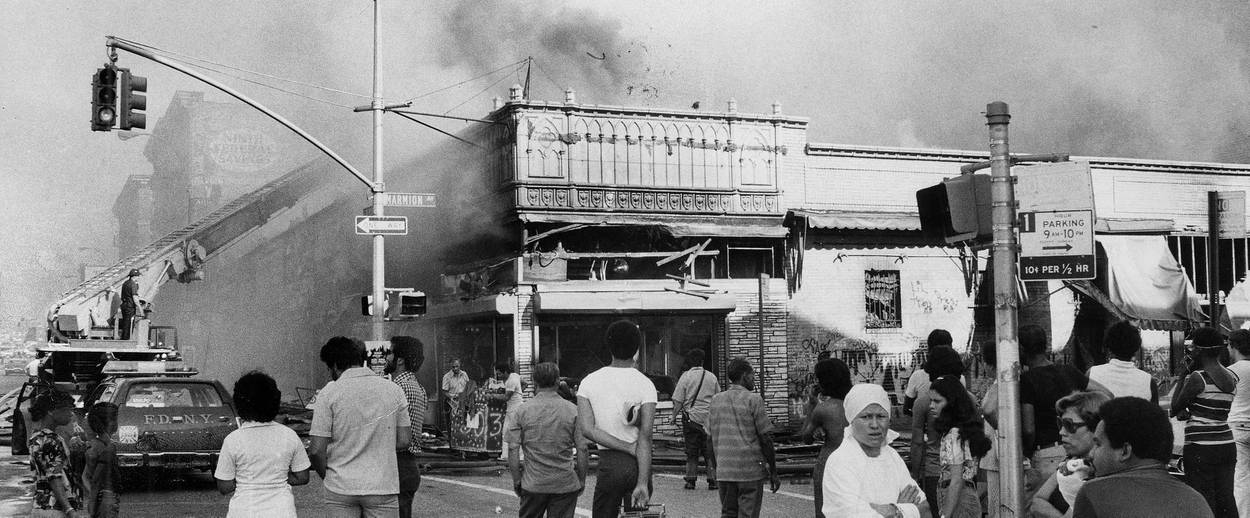

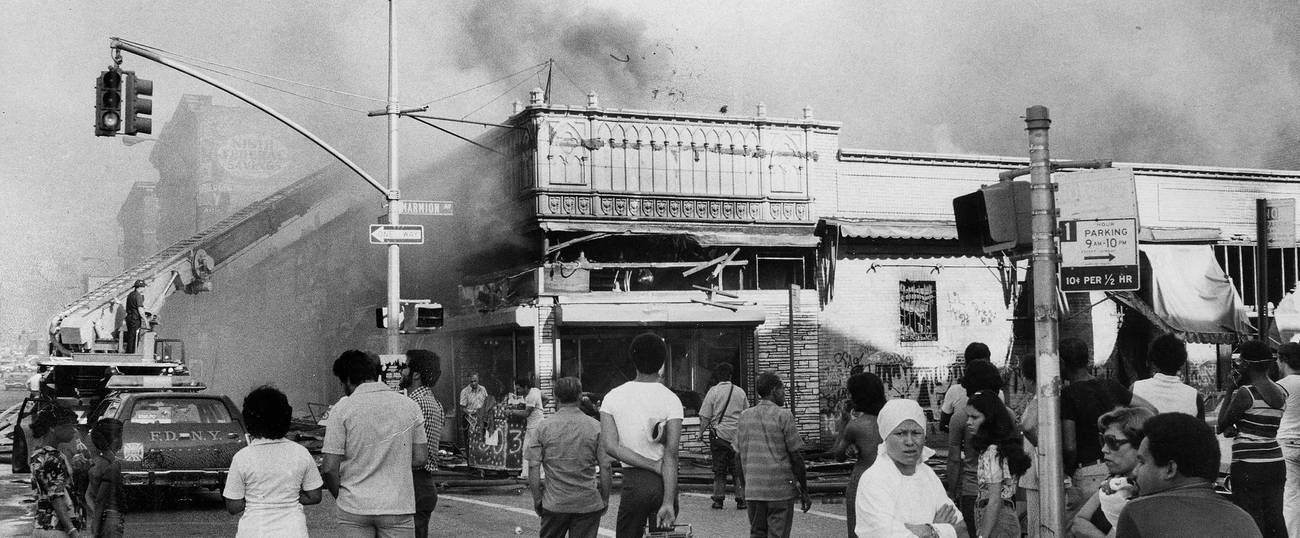

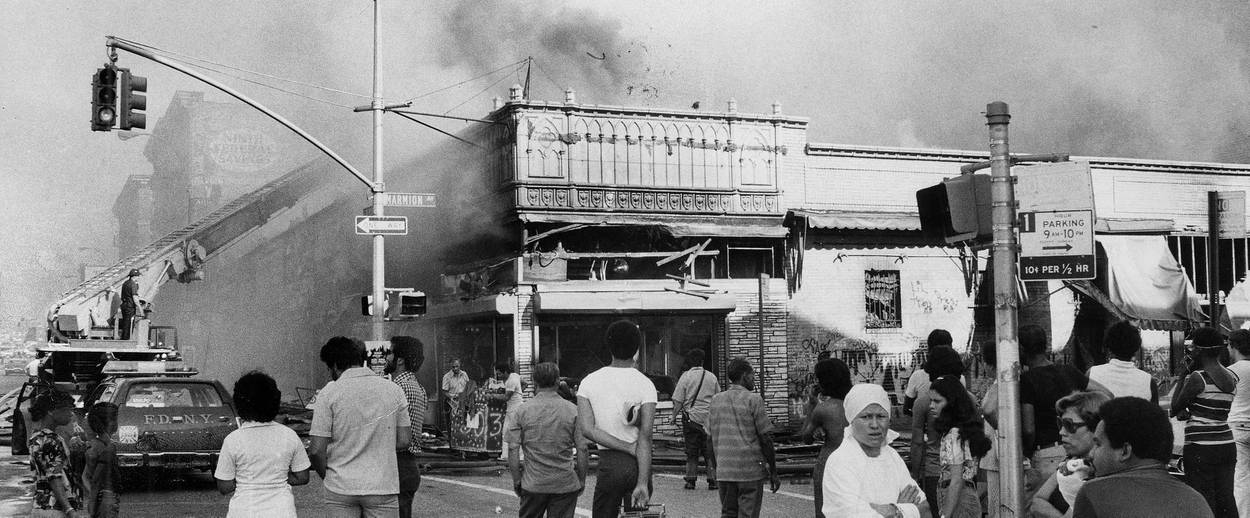

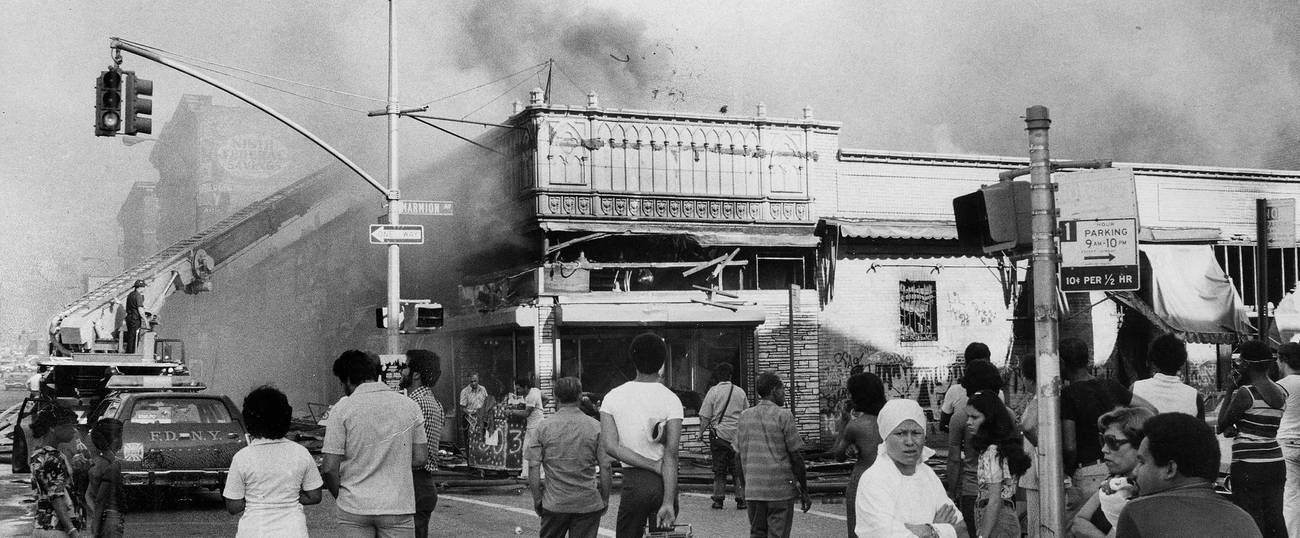

My first trip there, when I was 8, the Bronx resembled nothing of my father’s nostalgic reminiscences. It was a concrete and cobblestone jungle. This was in 1972, when fires raged in every other building and everything worthwhile had been ceded to gangs, drugs, and destruction. I got out of the car on Macombs Road and promptly stepped into fresh, mustardy dog crap.

The reason for that trip was that my grandfather’s cherished car had been stolen. Grandpa Abe, a house-painter immigrant from Kolomea, Galicia, had holed himself up on Macombs Road in his last months. A diminutive man, he walked to shul holding the jagged edge of a bottle for “protection.” His blue 1968 Chevy Impala—with air-conditioning and power steering and power brakes!—had been taken for a joy ride and was found a few short blocks away, shorn of its tires and God-knows-what-else.

Later that year Aaron Hisler—secretary of the Kolomear Friends Association, my grandfather’s landsmanschaft—died. I went with my father from our apartment in Queens to the Bronx in our 1970 Chevy to get “the books.” These were the books of the society: the by-laws, the dues levied dating back to 1903, the membership roster, the grave deeds that the society had bought for its members, and cemetery permits. My father, in a labored, rabbinical way, carried the files and notebooks down the stairs and into the car. He has carefully managed, chronicled, and documented everything for the group till this very day, dutifully sending out notices for membership (still $3 per year—it was written into the constitution that prices were forbidden to rise). Hisler cared deeply about Kolomea and he even recorded the history of the town (and its destruction at the hands of the Nazis) for posterity.

My father was one of the few of his West Bronx brethren who had entered the rabbinate and as one of the “sons” of Kolomea, the natural heir to Hisler’s work and sentiments. As such, Dad was called back to the Bronx often, when the Bronx Kolomears needed him to officiate, sometimes at Hirsch Bros. Funeral Home, sometimes at graveside. Such funerals were rapid, combustible, and built up a sizable tab (my father told me what the casket cost, the funeral home, the grave, etc.) including my father’s fee, which was always voluntary.

I remember one funeral—I think it was 1974 or 1975. There were three brothers, highly successful. One was a renowned artist out west, another a Washington lawyer; I don’t know what the third one did. They stood in a row, with matching receding hairlines. The funeral began with a great deal of decorum, but at graveside, the three brothers broke into an explosion of sobs. One of them, the shortest and least successful, was held up by his brothers as they walked back and forth to the grave several times until they finally left.

Set against the backdrop of a crumbling Yiddish culture, this was the one place many could become Jews again, through grief. Here they “celebrated” (not consciously, of course) a particular kind of Jewish grief, at once restrained and explosive. This old kind of Jewish funeral mashed together the two ways of life I had learned in the bosom of my sometimes airless but always loving family: the outpouring and freedom on the one hand, and the self-control and seriousness on the other. But at these occasions, I was also exposed to something far more explosive that registered in me as a rabbi’s son: the heretical (to me) hedonism of those who had discarded the restraint of Judaism and Jewish observance.

There were men named Sid, Harry, and Jack and women named Fay, Fanny, and Shirley. The men wore gold chains; they looked prosperous in their green Buicks and maroon Oldsmobiles. The women wore pantsuits. A few had frosted hair and smoked Salem Lights.

I would listen to the men banter just before the services. They talked about the Bronx. The Bronx was dying, dead. There was nothing left. Most of them were gone by now, the hundreds of synagogues sold off to churches or to drug rehab centers. The sound of sirens could be heard during services. They asked, who killed the Bronx? But another question seemed to hang in the air over the wooden pews in the funeral chapel: What will remain of the Bronx when our time comes?

My grandfather, an old widower, lived alone. We were terrified for him. But he refused to leave. How bad did it have to get for him to pull up stakes? “Come live with us, Dad,” my father entreated. Khvet bleiben do, my grandfather replied. “I will stay here.”

My father drew a deep breath. One last time he would try. “Dad,” he said, putting his hand on his father’s shoulder. “You may not want to leave the Bronx,” he said, pausing for effect, “but the Bronx has already left you.” With that, my grandfather broke down and wept. He left his home of 55 years the next week. Six months later he died.

Our trips to the Bronx became fewer and fewer. Eventually, they stopped altogether, but my father did not stop talking about the Bronx. It was too big in his mind and in those of so many others of his time—an almost mythical place in the firmament of American culture: a place of baseball and a cauldron of both ethnicity and Americanization, and later, a symbol of urban neglect and destruction.

About a year ago, I was driving on the Cross Bronx Expressway and honored the impulse to exit at Jerome Avenue to 1664 Macombs Road near Featherbed Lane. I hadn’t been there since I was 8 years old, in 1972. The building, my father’s birthplace, was still standing and in very good condition. In fact, the whole area of late has resurged. Yes, the old synagogues are movie houses or churches, and the Jews and even their ghosts are long gone, but the neighborhood is vital.

I walked on Featherbed Lane hoping that the ghosts of my father’s life would if not reappear, at least wink at me. There was once a candy store there called Eli’s that was my father’s portal to the world, a place where he would go in his knickers to buy candies, magazines, books, and toys. My father had told me that the owner, Eli, was a nonobservant Jew but oddly, was also a substantial Talmudic scholar from the famous Slobodka yeshiva in Lithuania. Of course, there was no trace of him or the store.

As I headed back to the car I thought of a line from the late Yiddish poet Avrohom Sutzkever: Of all the shining stars in the firmament, he asks, in the end, what will remain? The star that falls into a true tear. That’s what will remain.

The Bronx of yesterday, long gone, lives still in my imagination, a kind of American shtetl where everyone spoke Yiddish and behaved like a mensch. A place where people became Americans, yet still cried and grieved like Jews.

Alter Yisrael Shimon Feuerman, a psychotherapist in New Jersey, is director of The New Center for Advanced Psychotherapy Studies. He is also author of the Yiddish novel Yankel and Leah.