A Win for My Baby

Instead of the tragedy I had anticipated, the pain I felt during my high-risk pregnancy was a small victory

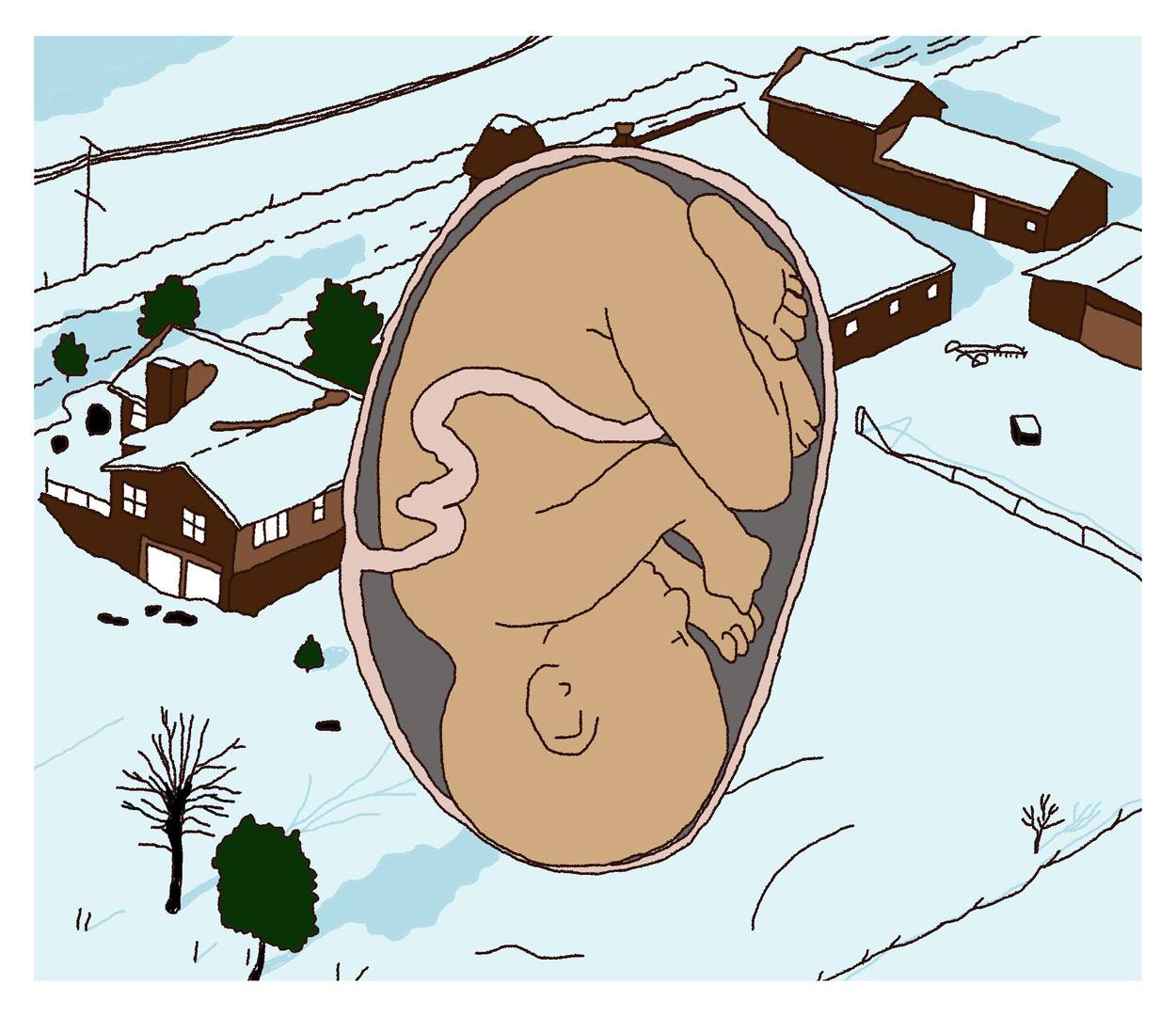

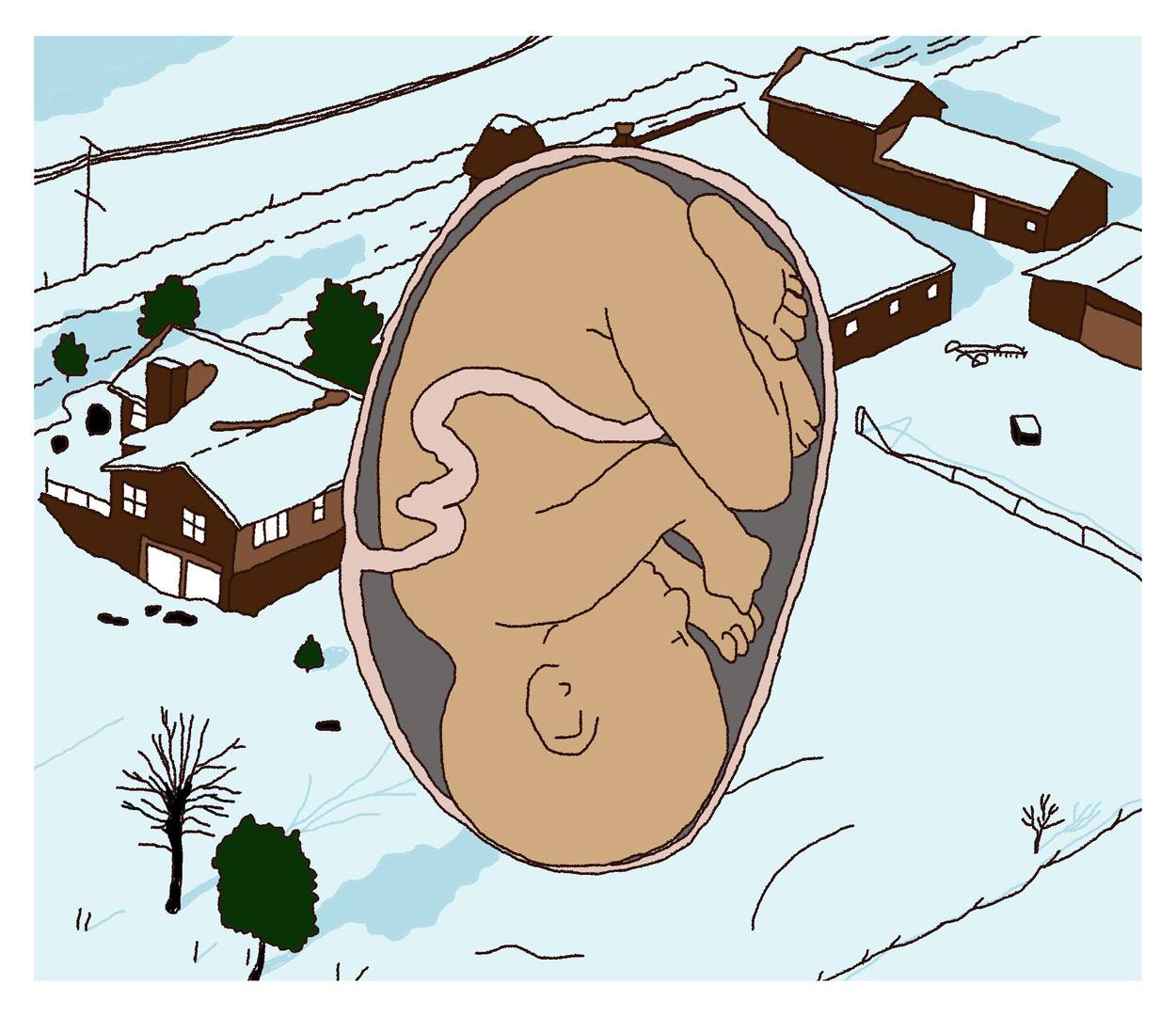

I was four months pregnant and walking around Manhattan with my new husband when I felt an unusual pain in my lower belly. The next day, an emergency sonogram showed I had three huge fibroids growing in my uterus right alongside the baby, and one of them was pressing on my cervix causing early effacement. The doctor told me to go to bed and stay there for the next five months. I’d made it through almost three months after that initial diagnosis, staring at the same four walls in my rickety old Hudson Valley farmhouse on a good and steady course.

My eyes shot open. In my sleepy fog, I could almost make out the red-orange glow of the sunrise peeking through the window. Something was amiss. A sharp stabbing pain in my lower right abdomen forced me to take a harsh breath in. I’d dismissed it the first time a few days back, but now it was much more severe. I was so close to the finish line now. Only 10 more weeks to go. I was afraid to breathe out. I pushed my sweaty, matted hair off my face. With another sharp pain, I braced for the worst and then placed my hand under the sheets to feel for blood. My hand came back dry. I turned to my husband, Chris, but he wasn’t there. Holding back tears, I called out that we needed to go to the doctor now. He didn’t hear me. He was on the other side of the house working on the renovations. I shouted his name in panic, but to no avail. Finally he appeared, ready to leave for work. I had already called the doctor, my face hot with fear.

Chris helped me to the car. He didn’t say anything that would lead me to think he was concerned, but when he held my arm as I navigated the stone steps, he grabbed it so tight he cut off my circulation, and I knew he was as worried as I was. I squirmed and wiggled, trying to contort my body into a comfortable position. Was this the culmination of all these months?

The baby leaving my body too soon? I hadn’t been good enough after all. Tears welled not only for the pain but for my failure. I prayed to God and I struck a bargain with my father whose death I was still mourning. “You will not let me lose this baby. I will not lose this child the way I lost you. If you do one last thing for me, keep this baby inside my body, alive. In return, I will pray for your eternal soul every day, lifting you up higher in the Lord’s eyes.” Suddenly I was a religious zealot, but I meant to keep my promise. Jews believe that each time you pray for a person’s soul, it rises higher in heaven. I swore if this baby lived, I’d pray so hard that my father’s soul would be catapulted right up to Yahweh’s throne.

When we saw the doctor, he was all business. He did not kiss my hand or entertain me with witty banter as he usually did. After an ultrasound and an examination, he said, “The baby is fine. You’re not miscarrying. Your fibroids are shrinking. There’s a war going on in there.”

I don’t remember the technical terms the doctor used, but he described a battle of wills between the monster fibroids and the baby for my blood supply, and even though the monsters were putting up a hell of a fight, they were losing. The pain I was feeling was from the monsters retreating. Instead of the tragedy I had anticipated, this was a small victory. It meant my little warrior was getting stronger. The doctor told me that he would prescribe painkillers, but there was something about them being bad for the baby’s kidneys, or liver, I couldn’t remember which.

When I arrived home, my mother called from Port Authority for an update and to tell me she was on her way up to our Hudson Valley farmhouse. Chris had called her while I was getting dressed at the doctor’s office. I got back into bed, relieved. Exhausted from both the morning’s events and the excruciating pain, I fell into a fitful sleep.

Hours later I awoke to my mother standing over me with a ladle in her hand. “Aileen, take the pills.”

“I’m not taking the pills.”

“You can’t just be in pain. Take the pills.”

“I’m not going to damage my baby.”

She hurried away in a huff, and soon I could hear her struggling to get the big stockpot out of the Lazy Susan. “I brought a chicken with me. I’ll throw something together,” she hollered.

I rolled over to stare out the bedroom window. If I took these pills, they would at best provide me with temporary relief, but there was a chance, however small, that my child would be born with two heads, or at the very least, half a liver. I had already given up most dairy (listeria), carbs (diabetes), and anything that tasted good (because, well, I was sure it would turn my child into a cyborg). Now painkillers had been scratched off the list, too.

“Talk to your brother,” my mother said, throwing the phone onto the bed.

“I’m not taking the pills,” I said, putting the receiver up to my ear.

“Take the pills,” my brother said.

“Don’t bully me.” I scrunched up my face as another wave of pain washed over me.

“Nobody is bullying you.”

“Dad would understand.”

“Bad argument. He died because he was stubborn and didn’t listen to his doctors.”

“Why do you care if I take the pills?” I breathed out away from the phone.

“Because you’re being selfish.”

“My pain is selfish?”

“You’re torturing your mother.”

“So, you don’t really care?”

“Only marginally. But it’s time to take care of yourself now.”

“I know you see it that way, but I’ve been fighting this war for months. This is just another skirmish. Why would I do something to screw up my chances now? Either way, it’s going to suck. I can deal with the pain now, or I can spend a lifetime maybe regretting my decision.”

After that, I thought of each stabbing rush as a win for my baby. I turned on chanting music and focused on breathing deeply, and it seemed to ease the pain.

“I brought you lunch. Eat.” My mother put a plate of carrots and hummus on my tray. We had been butting heads since I was in high school. But now that I was about to become a mother, I was beginning to see that no matter the circumstances, no matter how stubborn or angry I became, this woman would always be there, always love me, and, as a bonus, I would never go hungry.

“Thank you.”

“You’re welcome.” She stood there staring at me, waiting for me to take a bite.

Perhaps because I had come from a long line of Jewish women, I began thinking that the more I suffered, the more I would have a shot at keeping this baby alive. The waiting was almost over. I could deal with the pain. I couldn’t take the heat, though. I was on fire. That night I tossed and turned. There was something hard underneath my pillow. Half asleep, instead of looking for the culprit, I tried to roll my head away from it. Each time I’d drift off, I’d bump into it again. With eyes open and staring at the ceiling, I considered whether I wanted to pursue this knobby and unforgiving object, thinking that there was a very real possibility it was a petrified mouse. I rolled and threw my pillow to the ground, half expecting to find a carcass, but I couldn’t see in the dark and I was afraid to put my hand there.

Squinting I could just see the outline of something grayish. I put one finger out and touched it. It was cold. It had to be a dead mouse. This is what happens when you live in the country; you find vermin under your pillow. I looked again but couldn’t make out a face or limbs. Braver now, and with my curiosity piqued, I tapped it with the back of my hand.

It was a rock.

I picked it up and rolled it around between my palms, wondering if this had something to do with my mother’s bubbemeises, or old wives’ tales. I turned it over, looking for a Hebrew inscription. The woman was always putting ribbons, index-card prayers, and Jewish stars under my mattress to ward off the evil eye. There were black words on the rock, but I couldn’t make them out, so I put it on the nightstand, snuggled into my sheets, and threw my leg over Chris’ body before falling back to sleep.

The next morning, in the light of day, I picked up the rock again, turning it over, and there, written with a Sharpie pen, were the words: “I love you, baby. You rock. Chris.” I smiled.

It was a small gesture, but it meant everything.

This excerpt has been adapted from Knocked Down: A High-Risk Memoir, University of Nebraska Press.

Aileen Weintraub is the author of Knocked Down: A High-Risk Memoir. Follow her on Twitter @aileenweintraub.