Yiddish in the Catskills

Rokhl’s Golden City: Why attention must be paid to the history of the Borscht Belt

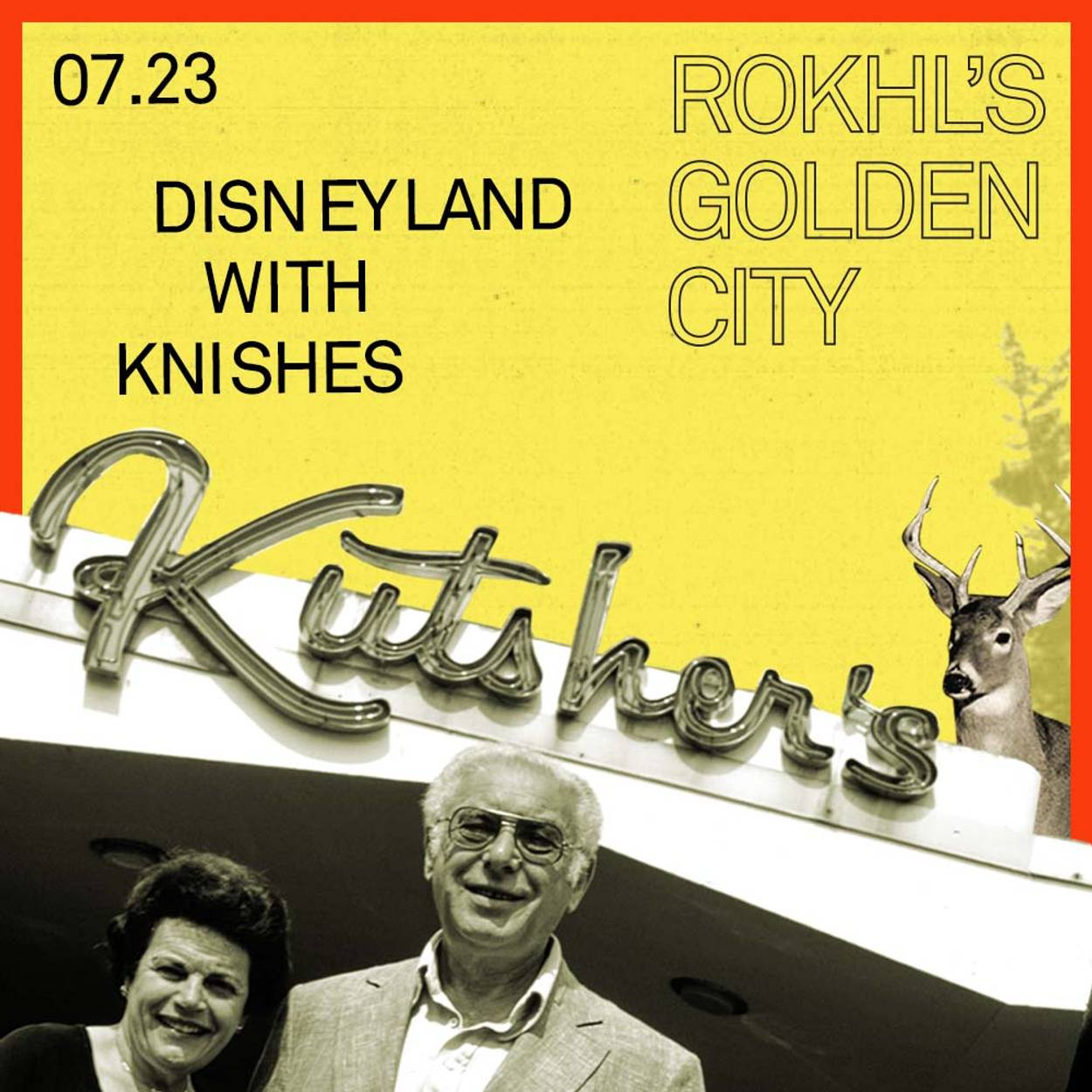

“A Disneyland with knishes.” That’s how Canadian novelist Mordecai Richler wryly described the Catskills he found on a 1965 visit for Holiday, a magazine dedicated to “civilized entertainment.”

The area was alternately known as the Sour Cream Sierras and the Jewish Alps in its heyday; today there is only the Borscht Belt (of blessed memory). More than a geographic locale, the Borscht Belt “signified a loose confederation of some thousand Catskill Mountain resorts, named for the Eastern European Jewish clientele who filled the rooms with laughter and rumor, wandered the greenery, searched for mates, and consumed four Lucullan meals a day, including a midnight snack.” That’s Stefan Kanfer’s description in A Summer World, his 1989 history of the Jewish Catskills. “In between, they cheered the tummlers, a Yiddish word for the manic, all-purpose entertainers who were the mainsprings of these resorts.”

That image of the Catskills persists today: a shrieking, shpritzing, fressing, Jews-only paradise (and antisemite’s nightmare), where mating was pursued with the kind of collective single-mindedness to make a salmon pause upstream in admiration. With some degree of ambivalence, Richler called the hotel guests “sitting ducks for satire.” Weren’t these Jews simply living the American dream of abundance and security?, he wondered. In any case, he assured us, hotel guests had a sense of humor about themselves. Whatever you might say about them, they had already said, loudly, and worse.

The Jewish Catskills experienced a decline in the 1960s, hurt by the ubiquity of television, air conditioning, cheap airfare, and the curse of social mobility. (Not to mention that hotels in other regions that had once proudly closed their doors to Jews were now legally prohibited from doing so.) But before that, the Borscht Belt was more than a place, it was a densely populated world of its own, an engine of American Jewish culture, producing an astounding array of comic talent and shaping American comedy for decades.

Richler notes that at a big hotel like Grossinger’s (“the G”), you could expect to be entertained by top-shelf TV comics: “They reveal the authentic joke behind the bland story they had to tell on TV because Yiddish punchlines do not make for happy Nielsen ratings.” At Grossinger’s, making it in America sounded like a comic at home with Yiddish punchlines, and the laughter of the audiences that craved hearing them.

But not every hotel was Grossinger’s, and things sounded very different when shrieks of laughter were replaced by defiant silence. Kanfer recounts the experience of Joan Rivers, who cut her teeth as a young comic in the Catskills, and whose audiences she called “the worst in the world.” Guests didn’t pay for entertainment, and felt at total liberty to express their disdain. But the worst of the worst, according to Rivers, was “the Benz Hotel where nobody spoke English and the interpreter onstage repeated everything I said in Yiddish … Every line bombed twice.”

At Grossinger’s, the sound of Yiddish was a secret handshake, something that connected comic and audience in a mostly English-language milieu. What happened at the Benz, however, points to a very different genre of Jewish presence in the Catskills, one that resisted translation.

In the late 1930s, for example, a group of families established a new bungalow colony where Yiddish would be the language of high culture, not punch lines. Novelist Martin Boris describes the Grine Felder (Green Fields) colony as “summer home to the most concentrated assemblage of Yiddishist elite anywhere on Earth.” Opera, classical music, literature, and drama were important activities, and children were an integral part of that cultural life. Those who wanted to summer at Grine Felder first had to be “evaluated by the cultural committee as to his or her possible contribution to the various cultural activities going on.”

Despite the idealism of the organizers, they still had to contend with material realities. Yiddish theater in New York was in a period of decline. Director Zygmunt Salkin met that depressing reality with an absurd plan. He took I.L. Peretz’s play Bay nakht afn altn mark (At Night in the Old Marketplace) and created a new English translation. He then dragged his friend I.B. Singer up to Grine Felder to oversee the staging of the (previously considered to be unstageable) play.

By the end of the summer of 1938, the play had come together. It still failed to find a theatrical home in New York’s shrinking Yiddish theater scene. Those who could transition to the mainstream American stage were doing so, with the husband and wife acting team Joseph Buloff and Luba Kadison among them. Buloff was successful enough that he would originate the role of Ali Hakim when Oklahoma! premiered on Broadway in 1943.

Despite his success, Buloff never abandoned the Yiddish stage. With Kadison, he created a Yiddish adaptation of the play that shook the foundations of American theater at midcentury, Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. Salesman premiered in 1949, and Miller personally kept tight control over subsequent stagings and adaptations, with one notable exception. In her fascinating essay “Attention Must Be Paid: Death of a Salesman’s Counter-Adapted Yiddish Homecoming,” historian Debra Caplan tells the amazing story of how Buloff and Kadison simply walked around Miller’s many stipulations (along the way, premiering their Yiddish Toyt fun a seylsman in Argentina) and even gained his enthusiastic consent for their successful Brooklyn production of Toyt fun a seylsman in 1951.

After the triumph of their Death of a Salesman adaptation, Buloff found quite a bit of work in American television, getting roles on Ben Casey, Naked City, and other shows. But what interests me most is his 1954 summertime arc on the extraordinarily long-lived sitcom The Goldbergs.

Over seven episodes in the summer of 1954, Buloff played Mr. Pincus, owner of Pincus Pines, the hotel where Molly and Jake Goldberg bring their family for a Catskills holiday. The episodes themselves aren’t terribly interesting. And that’s not surprising. In 1956, Gertrude Berg (herself the daughter of Catskills hoteliers) told Commentary:

You see, darling … I don’t bring up anything that will bother people. That’s very important. Unions, politics, fundraising, Zionism, socialism, inter-group relations, I don’t stress them. ... After all, aren’t such things secondary to daily family living? The Goldbergs are not defensive about their Jewishness or especially aware of it. ... I like to keep things average. ... I don’t want to lose friends. (Quoted in Donald Weber’s 1998 article “Taking Jewish American Popular Culture Seriously: The Yinglish Worlds of Gertrude Berg, Milton Berle, and Mickey Katz.”)

“I like to keep things average” isn’t exactly the kind of credo from which timeless art emerges. But that wasn’t the point. For its legions of viewers, The Goldbergs was comfort viewing, a heymish (but not too heymish) example of an average American family that just happened to be Jewish.

The Pincus Pines episodes touch on familiar Catskills tropes: quality of the dining room food, distribution of tips among the hotel staff, romantic intrigue among young singles, romantic intrigue among old marrieds, and gossiping on the porch. (You can even catch the elegant Luba Kadison as one of the gossiping women in this episode.)

But what I really love about this arc is getting to see a legendary performer like Joseph Buloff in action. Just watch him enter the Goldberg’s apartment for the first time in this episode. The man had presence.

On the Aug. 3 episode, Celia Adler, daughter of Yiddish impresario Jacob P. Adler, shows up as a guest star. She plays the wife of a kindly but delusional older man, played by Mikhail Rasumny. In 1944, Rasumny told The New York Times that he had arrived in the United States with the Moscow Art Theatre and decided to stay. He was later threatened with deportation, whereupon he was bailed out by a wealthy patron of the New York Yiddish theater and made the head of the “Yiddish Theatre Group.” It’s unclear what exactly happened next, but Rasumny left the Yiddish stage, returned to dishwashing for a time, and then headed out to Hollywood, where he found some success.

My favorite episode of the Pincus Pines storyline is the last. We get an extended peek into the lives of the hotel staff as they plan their end-of-season talent show. Watch the French pastry chef (Marcel Hillaire) steal the show with his song and dance.

Hillaire’s own story of being a Jew hiding in plain sight in Nazi Germany (at one point working for Albert Speer!) is absolutely bonkers and should have already been made into multiple Hollywood movies. The German Hillaire came to America after the war and reinvented himself as a Frenchman, playing dozens of roles similar to the one he plays here.

What I love about these episodes is that within this rather bland American sitcom gruel hides a dazzling array of performances, and surprising meanings. We may never be able to see Buloff playing his Yiddish Willy Loman, but we can see him here in English, as the long-suffering Pincus, surrounded by other luminaries of the Yiddish (and European) stage.

In Debra Caplan’s article on Buloff’s Death of a Salesman adaptation, she makes a provocative argument:

“In a landscape in which the once legendary Yiddish theatres of New York were on the brink of extinction, this production’s suggestion that the most successful post-war Broadway drama belonged to the Yiddish theatre was a powerful argument for the persistent centrality of the Yiddish stage to American theatre at large. If Willy Loman was more at home in Yiddish-speaking Brooklyn than on English-speaking Broadway, then perhaps the post-war Yiddish theatre was not, as its critics had charged, an art form on the periphery of Jewish cultural life, but rather the nucleus of mainstream American theatrical creativity.”

Caplan frames Buloff and Kadison’s Toyt fun a seylsman as a counteradaptation, a work that disrupts and enriches the original text’s reception. I can’t make any grand conceptual claims for The Goldbergs and Pincus Pines. But I do find something arresting within the placement of these particular actors in this particular dramatic location. It’s tempting to say that at Pincus Pines, one can almost read the Yiddish high culture back into the Yinglish Catskills. At minimum, as Linda Loman might say, attention must be paid.

It’s not surprising that Mordecai Richler was sent to observe the Catskills inhabitants in 1965. He made a splash with his 1959 novel, The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, whose action is set substantially in the Quebec analog to the Catskills, the Laurentian Mountains.

Though I’m a die-hard New Yorker, my family was not a Catskills family and I’ve spent far more time in the glorious Laurentian Mountains than the Catskills, thanks to the annual KlezKanada festival.

The Laurentian Mountains have always been intimately tied to the life of Jewish Montreal, and especially Yiddish Montreal. A Jewish tuberculosis sanitarium was built in 1930 to meet the special needs of Montreal’s Yiddish speaking population. The sanitarium inspired Sholem Shtern’s Yiddish novel in verse, Dos vayse hoyz (The White House). The sanitorium was located in Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts, which just happens to be the same town where KlezKanada is held (in normal, nonpandemic times).

Yiddish has always had a lively presence in the Laurentians. The only place I enjoy going to WalMart is when we’re in Sainte-Agathe, because we always end up eavesdropping on Yiddish-speaking Hasidim.

There’s still time to register for KlezKanada (Aug. 23-27), and because it will once again be held virtually, it’s easier than ever to participate. This year there will be a special theater workshop called Vu bistu geven/Where Were You, which will explore Dos vayse hoyz, as well as reflecting “on Yiddish life in the Laurentian mountains, Indigeneity, and what mutual aid could look like in this current moment.”

ALSO: My friend Aaron Bendich has a terrific Jewish music show on WJFF Radio Catskill. He has a knack for finding the deepest cuts of postwar klezmer and Yiddish music. On July 29, the Yiddish Book Center will present a multimedia program called Borscht Beat: Behind the Scenes with Aaron Bendich. Register here … Here in the Golden City, we know that Jewish linguistic maximalism is the name of the game. Sarah Aroeste, my wildly talented friend from the Ladino side of town, will be performing with Shai Bachar in Ladino Music From Yesterday to Today, Sunday, Aug. 8, at 3 p.m. You can watch online or in person at the Museum of Jewish Heritage. Tickets are required … If you’re going to be in London, you can attend the Homos and Houmous queer Jewish cabaret, hosted by Chanukah Lewinsky. With drag performance, poetry, and comedy. At the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, Aug. 9, starting at 7:30 p.m.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.