Cooking Up Spain’s Jewish Past

Medieval Sephardic recipes come out of hiding at La Vara, a new restaurant in Brooklyn that reconnects Spanish cuisine with its Jewish roots

Downstairs in the kitchen at La Vara, a 44-seat Spanish restaurant that opened in Brooklyn’s Cobble Hill neighborhood a few weeks ago, a line cook tosses hunks of marinated lamb into a pressure cooker. Nearby, another cook mixes preserved kumquat peel into a tub of olives before turning around to plate an order of beef tongue braised in tomato-caper sauce. As in all new kitchens, the pace is hectic as the staff learns its way around an unfamiliar space. But for chef Alex Raij, everything feels like it’s in exactly the right place.

La Vara joins a small but growing cluster of nouveau Jewish eateries in the neighborhood: The Montreal-style delicatessen Mile End, the appetizing store Shelsky’s Smoked Fish, and the egg-cream-pushing Brooklyn Farmacy & Soda Fountain are all a short walk away. But unlike its neighbors, La Vara’s culinary explorations are Sephardic—and Raij said she does not aim to “elevate nostalgic comfort food,” as many of her contemporaries are credited with doing.

La Vara is the newest venture for Raij and her husband, Eder Montero, who co-own two Spanish restaurants in Manhattan, the tapas bar El Quinto Pino and the Basque-inspired Txikito. La Vara is also Spanish (pork and seafood dishes are scattered liberally across the menu), but with a twist: Many of the restaurant’s dishes are inspired by the medieval Jewish and Islamic cuisines that shaped the food of southern Spain—a legacy that virtually vanished for centuries but is now being revived by Raij.

Raij isn’t Spanish; she was raised in Minnesota by Argentine-Jewish immigrant parents. “My husband is the Spanish one, he’s Basque,” she said of Montero, who moved from Bilbao to New York City in 1999 to work as a chef, and whom Raij met shortly after in the kitchen of the now-closed restaurant Meigas. “I have always looked for ways to feel more personally tied to his food.” The Sephardic legacies woven through La Vara’s dishes serve as a point of connection between their respective Spanish and Jewish backgrounds.

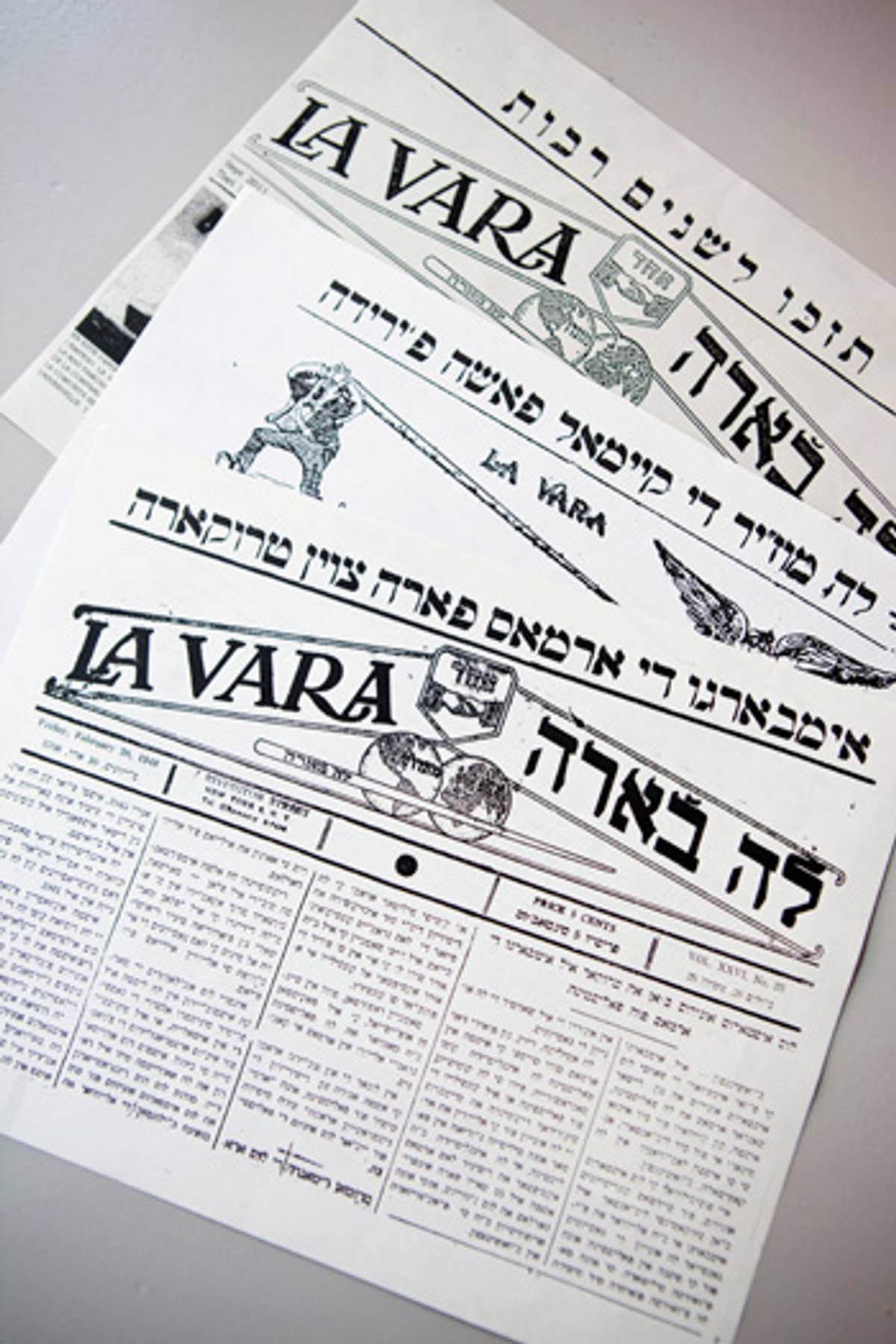

La Vara is named after the longest-running of nearly 20 Ladino-language periodicals published in the early 20th century by Sephardic immigrants in America. La Vara, which was published on the Lower East Side from 1922 to 1948, was known for its social and political satire and community news—the Ladino answer to the Forverts, the Yiddish-language Forward. Raij found the name, which translates to “branch” or “staff,” while Googling the words “Sephardic Brooklyn,” and said it immediately clicked. “We have a mural at Txikito that reads, ‘When you leave your country, your branches become your roots,’” she said. “That feels true to my parents’ experience leaving Argentina, and certainly true of my husband leaving Spain.”

The culinary landscape La Vara explores evolved over an eight-centuries-long period in southern Spain, where Jews flourished in relative peace under Arab Muslim rule. The period was defined, in part, by cultural symbiosis: “Jews … were deeply rooted in the local society, alongside the Arabs, Berbers, and Mozarab Christians,” writes Claudia Roden in The Book of Jewish Food. In addition to wearing Arab-style clothing and speaking Arabic, Jewish Spaniards for the most part ate the foods their Muslim neighbors introduced to the region—things like eggplants, chickpeas, artichokes, almonds, oranges, and quince. According to A Drizzle of Honey: The Lives and Recipes of Spain’s Secret Jews by David M. Gitlitz and Linda Kay Davidson, Jews in Spain “ate tangy meatballs” called albóndigas (which likely stems from the Arabic word for “round”) and “covered their dessert pastries with sweet sugar sauce.” And like many medieval cooks, they perfumed foods with copious, overlapping spices and herbs.

Medieval Spanish Jewish cooks did, of course, make adjustments to the local cuisine, primarily to accommodate their ritual and kosher dietary laws. They avoided pork, rabbit, and shellfish, though Gitlitz told me that there is “very little evidence that they actively separated milk and meat.” They also salted and soaked their meat, and prepared hearty, long-simmering stews called adafina (Arabic for “hidden”), which did not require active cooking during the Sabbath.

Everything changed with the Inquisition, however, when Spain’s Jews were either expelled or forcibly converted to Christianity. At that point, the same customs that once set Jews apart began to be used as testimony in trials against conversos accused of maintaining their ties to Judaism. The Inquisition turned neighbor against neighbor, as citizens exposed suspected crypto-Jews to authorities. A Drizzle of Honey recounts many of these stories of betrayal, including that of Beatriz Núñez, a convert who was burned alive after her maid testified against her for continuing to prepare a Sabbath stew made of lamb, chickpeas, and eggs. Other crypto-Jews were sentenced for getting caught lighting Shabbat candles, removing the prohibited sciatic nerve from a leg of beef or lamb, snacking on cold salads with friends on Saturday afternoon, or refusing to eat dishes made with pork.

As a result, Jewish cooking in Spain—or what little was left of it—was forced underground and, over the generations, faded almost entirely. A black-and-white graffiti-style painting on La Vara’s otherwise minimally decorated walls evokes this sense of hidden-ness: Two young girls in ruffled skirts crouch side by side, one whispering a secret into the other’s ear.

But on the menu at La Vara, traces of Islamic and Jewish cooking, both subtle and explicit, are brought out of hiding. Take the berenjena con miel, a dish of crisp-fried eggplant served with melted cheese, honey, and black nigella seeds, or the garbanzo rinconcillo, a hearty chickpea and spinach stew reminiscent of adafina. There’s also alcachofa, fried artichokes with anchovy alioli, and La Vara’s take on albóndigas, made with lamb. On the dessert menu, egipcio, a date and walnut tart, is flavored with orange blossom water, and a sweet rice custard called natillas de arroz con leche comes scented with cinnamon, rose, and rosemary.

Through its menu, La Vara helps to revive Spain’s Jewish cuisine and gives Sephardic Jews a reason to celebrate their legacy—literally. When the grandson of La Vara’s last publisher, Joe Halio from Great Neck, N.Y., heard about the restaurant opening, he immediately contacted Raij and offered to bring her archived broadsheets of the old Sephardic newspaper. Raij, in turn, invited him to their opening-night party. “Joe told me he planned to drop by and say hello,” Raij said. “But he ended up staying and partying with us the whole evening.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.