Culinary Tales of Hoffman

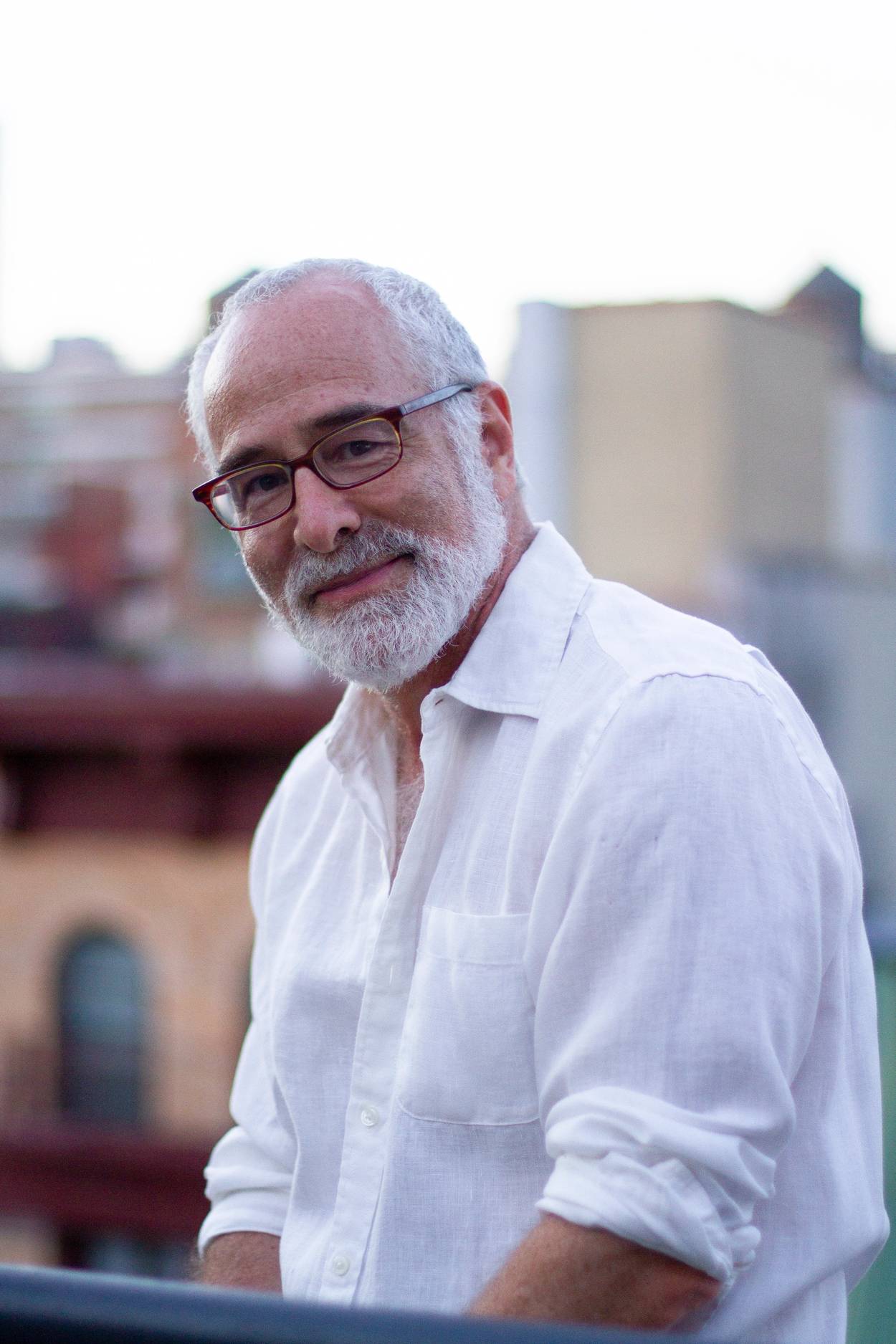

Renowned New York chef Peter Hoffman preserves the city’s past in his new memoir, ‘What’s Good?’

Anyone who has ever lived in New York City for any reasonable stretch of time has two relationships with the ever-changing metropolis. The first is defined by a love for the city exactly as it was when they arrived, paired with a lamenting over all the ways it has changed. The second is a (rarely admitted) wish to have experienced the city in another of its golden eras. For me, reading What’s Good?, the newly published memoir by chef Peter Hoffman, evoked powerful feelings in the latter category.

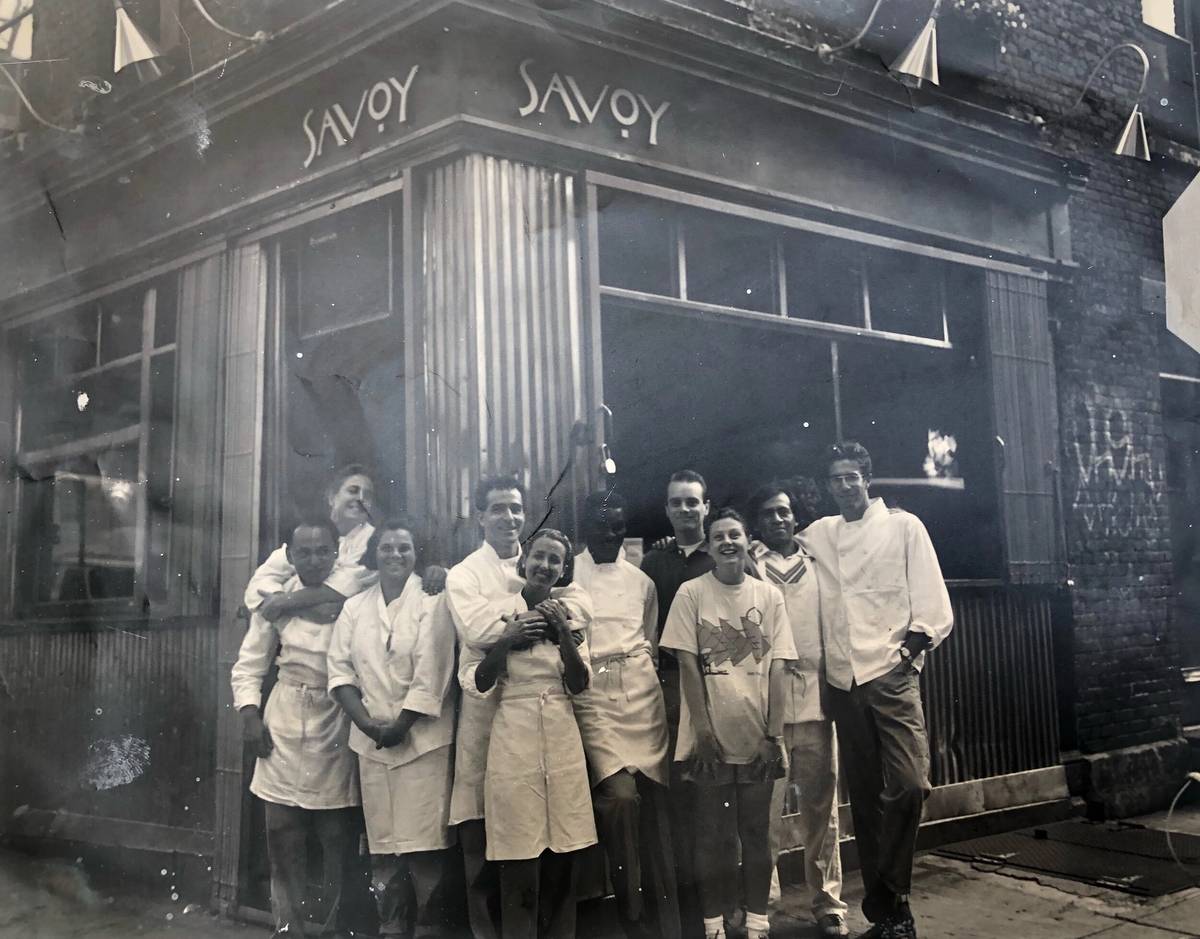

Hoffman is best known as the chef and co-founder, along with his wife Susan, of Savoy—the celebrated neighborhood restaurant he opened in 1990 and ran for two decades—as well as its sister restaurant Back Forty. Savoy was located in Manhattan’s SoHo district, when it was a haven for artists rather than an upscale shopping mall. And Hoffman’s Mediterranean-influenced, improvisational cooking style both reflected and helped shape the neighborhood zeitgeist.

Along with ahead-of-their-time chefs like Edna Lewis and Alice Waters, Hoffman also approached food and cooking with an eye toward seasonality, and devotedly sourced ingredients from local producers. Long before concepts like farm-to-table or nose-to-tail cooking entered the mainstream culinary lexicon, he was a regular at Manhattan’s Union Square farmers market.

“In the early Savoy days, my English three-speed bike with a front basket and rear panniers sufficed to haul my purchases to the restaurant,” Hoffman writes of his forays to the market. He soon graduated to a larger rig, which he describes as “a front-loaded stretch-limo bicycle.” The new bike allowed him to drop his children off at school, then load up with crates of squash and Brussels sprouts, or kegs of locally fermented apple cider before most people had had their morning coffee.

What’s Good? (the title refers to a standard market greeting that means both, “What’s happening?” and also “What produce is freshest today?”) includes several essays on ingredients—things like maple syrup, strawberries, pears, and rosemary—that have been resonant to Hoffman as a chef. In these chapters, readers discover that ceramic models of garlic have been discovered in 5,000-year-old Egyptian tombs, and that it takes 40 gallons of maple sap to produce a gallon of pancake-ready syrup. These interludes are enlightening, but the book shines brightest when Hoffman digs into his personal narrative, which tracks alongside the city’s (and country’s) larger awakening around food.

Hoffman grew up in a staunchly secular Jewish home in Tenafly, New Jersey, with a father whose complete rejection of organized religion snuffed out any opportunity for exploration. “He’d blurt out venomous words before even entertaining a spiritual consideration,” Hoffman writes. As a child in the 1960s, he did not attend synagogue or Hebrew school, and had only a passing connection to Jewish holidays. “We lit Chanukah candles and left juice out for Santa under a small tree,” he writes of his family’s winter celebration.

But what Hoffman did not receive in religious exposure, his parents made up for by introducing him to the delights of eating across the river in New York City: strudel from the Upper East Side’s Hungarian bakeries, singed Armenian lavash in the Bronx, feijoada at Casa Brasil, and babka, bagels, and smoked fish at Zabar’s. It was there, late on Saturday nights when theatergoers packed the fish counter to stock up for their Sunday morning appetizing spreads, that Hoffman writes, “I became convinced that the city’s round-the-clock vibrancy was ... a necessity of life. The intense verve was an intoxicant and I couldn’t wait until I would be of age to partake; I was going to live here.”

Hoffman’s parents also encouraged the personal and professional meanderings that led toward his career as a chef and restaurant owner—even when polite society (read: his parents’ friends) didn’t approve. Along the way, Hoffman worked in kitchens in Vermont, California, and New York, joined a crew of shad fishermen on the Hudson River (an experience that would later inspire Savoy’s annual spring shad feasts), studied under chef Madeleine Kamman in France, and practically took up residence at Dean & DeLuca’s cookbook section, where authors like Marcella Hazan, Diana Kennedy, Paula Wolfert, and Richard Olney provided a global culinary education.

As a young seeker in the 1970s, he gravitated toward the Eastern-influenced, psychedelic-infused lessons espoused by Ram Dass rather than the medieval Jewish wisdom of Rambam. Later, the writings of farmer-activist Wendell Berry, particularly his watershed treatise The Pleasures of Eating, in which Berry radically pronounces, “Eating is an agricultural act,” became his scripture. Berry’s words, Hoffman writes, “are as close to a religious text as I ever hope to embrace.”

And yet, there is something palpably “Jewish” about Hoffman’s pursuit of community, as well as his approach to food. In the anxious months leading up to Savoy’s opening, Hoffman found a model in the story of Nachshon, the Israelite elder who stepped first into the Red Sea, before the waters had parted. “I first encountered Nachshon reading Michael Walzer’s Exodus and Revolution, a left-wing interpretation of the biblical journey (my dad begrudgingly approved),” he writes. “Nachshon’s courage was inspirational for me—diving into unknown waters was imperative if I was going to create the future I envisioned.”

Along with a long-running dinner series, where Hoffman invited speakers (including a young Michael Pollan, then an editor at Harper’s) to enlighten diners about various food-related topics while they ate, Savoy also hosted annual Passover Seders. Growing up, Hoffman spent the Seders at his grandparents’ house, feeling “infinitely bored” and “hiding under the table ... anxious to know how soon we would be getting to the eating part of the evening.” And yet those meals made a lasting impression.

The first Passover of Savoy’s tenure, the restaurant stayed open. “I wanted to be a nondenominational chef-owner who just happened to be Jewish,” Hoffman said. But he admitted that missing the Seder hurt his heart. So he and another Jewish chef on staff pulled together an impromptu Seder plate—herbs, a quick chop of apples and walnuts for charoset, a roasted lamb bone and egg, and freshly grated horseradish—and speedily reenacted the Passover story for their fellow cooks at the pre-dinner service staff meal. That fully improvised moment evolved into a long-running Seder for diners, featuring global Jewish dishes and even a house Haggada.

Meanwhile, at Savoy and Back Forty, Hoffman maintained his unwavering stance on seasonal cooking. “It’s easy to find April menus from ‘market-driven’ chefs that abound in English peas, favas, string beans, and sugar snaps even though none of these vegetables could possibly be growing in our region yet,” he writes. “Should I give in, jump-start the season, and serve flashier ‘spring’ foods or should I hold my ground …?” Ultimately, he decided, “I prefer the truths of my inconveniences,” sounding not unlike a traditional kashrut observer, who chooses to forgo momentary culinary comforts for something they deem more meaningful.

My own tenure in New York City, which began immediately after college graduation in 2004, overlapped by several years with Savoy and Back Forty. Unfortunately, I was in my early 20s, foolish, and too busy chasing a night’s worth of drinking with $1 slices of pizza to ever eat at either.

Meanwhile, Hoffman began to see the writing on the wall. The neighborhood had shifted, as New York City neighborhoods do—and soaring rents, plus an influx of diners who craved more mainstream tastes, made survival tenuous. In 2011, Hoffman closed Savoy after 21 years and turned it into Back Forty West, serving the same hamburger-focused menu as Back Forty’s East Village location. The burgers were impeccably made with carefully sourced beef, but the change sapped Hoffman’s creative energy. “It was one thing to have the East Village burger location as a complement to my fine-dining restaurant establishment in SoHo,” he writes. “It was a whole other thing for casual burger joints to be the sum of what I did.

In 2016, Hoffman turned the lights off one last time and sold off the entirety of the restaurants’ contents—wall art, tables, glassware, pepper mills, espresso spoons—to longtime customers and friends. “I participated in the gentrification of the neighborhood and gentrified myself right out of a job,” Hoffman writes.

I mourn having squandered my chance to experience Hoffman’s cooking, and to time-travel to a magical era of possibility in a SoHo that no longer existed beyond Savoy’s corner windows. Fortunately, like a pickler packing cucumbers and tomatoes with salt into ceramic crocks to be enjoyed long after the season has ended, Hoffman’s What’s Good? preserves the messy, wild beauty of that moment for others to enjoy.