Life After Brisket

Veganism in Israel is taking hold among the Orthodox, who use textual sources to argue against all meat consumption

A little more than two years ago, 36-year-old Jeremy Gimpel, a Modern Orthodox Israeli rabbi, political activist, and radio and television host, finally watched a YouTube video taken in a kosher-certified chicken slaughtering plant. A vegan friend had encouraged him for months to take a look at various videos about the ugly side of industrial food production. But Gimpel, who back then found vegans annoying, had dismissed his friend, pointing out that halakha not only allows for eating meat, but also prohibits the sort of animal torture that such slaughterhouse videos purported to show.

“I was like, that’s what goyim do,” Gimpel told me. “But then he sent me YouTube links to a kosher slaughtering house. And I couldn’t stop watching. I was shocked. I was like, that’s not kosher. I don’t care what the rabbinate says.”

Gimpel immediately stopped eating all animal products, forgoing the schnitzel and meat-laden cholent that were once the staples of his Shabbat lunch. Gimpel, who unsuccessfully ran for 2013 Knesset on the right-wing HaBayit HaYehudi ticket and is now vice chairman of the World Mizrahi Movement, then dedicated an episode of his weekly “Israel Inspired” podcast to American animal-rights activist Gary Yourofsky.

With his frequent comparisons of animal slaughter to the Holocaust, Yourofsky was an unlikely topic for Gimpel, who usually dedicates his show to the right of Jews to pray on the Temple Mount and other religious-political topics.

On this particular episode, Gimpel not only looked at the way animals are treated in food production but also delved into the Bible, Talmud, and strains of Jewish thought focusing on animal consumption. “There is a deep, deep Jewish belief that there is a sanctity to life,” Gimpel said on the podcast. “Gary Yoroufsky is tapping into something very Jewish here.”

Even though Jewish tradition has embraced meat-eating and the laws of kashrut outline how to slaughter animals, today’s industrial meat production causes animal suffering, which is prohibited in the Torah, Gimpel told me. That nefarious production process includes, he went on, milk and egg production.

“The spirit of the law is being trampled by modern-day factory farming,” Gimpel told me. This line of thinking explains veganism’s growing popularity among Israel’s religious populations, mainly in Modern Orthodox quarters, but also, in part, in the more insular haredi world. Although no rabbi has yet issued a psak, or official declaration, against eating meat and dairy products, about a year ago, Beit Hillel, a consortium of 120 Orthodox rabbis, scholars, and community leaders in Jerusalem, issued a paper calling on Jews to reduce their meat consumption in order to alleviate animal suffering.

Among the Orthodox in Israel, veganism is “getting stronger,” said Yossi Wolfson, an animal-rights activist, vegetarian since 1975, vegan since 1992, and coordinator of the Ginger Vegetarian Community Center in Jerusalem. “It’s not a revolution, but it’s a process.”

And Ori Shavit, a writer who founded the blog Vegans on Top, says she has seen a rise in inquiries from Orthodox vegans about vegan cooking workshops she runs. “More and more people ask me if it’s kosher,” she said.

Veganism in Israel got a movement-defining boost in 2010, when local animal-rights activists added Hebrew subtitles to one of Yourofsky’s speeches on YouTube. Now 13 percent of Israelis identity as vegetarian or vegan, and about 5 percent are strictly vegan, eschewing fish, milk, eggs, and honey, according to Wolfson. Israel is the only market in the world where international chain Domino’s offers a soy-cheese vegan pizza.

Vegans in Israel are driven more by animal rights than by health concerns and adopt a militant stance in defense and promotion of their cause; members of the animal-rights group 269 Life once publicly branded themselves with hot irons to show solidarity with animals, and there have been incidents of scattered heads of cattle, dead chickens, and fake blood sprayed on streets and inside agricultural-related offices to protest meat production and consumption. Besides that, the movement manifests itself peacefully, with dozens of new vegan restaurants opening up and established restaurants adding vegan dishes to their menus. Arguably the strongest sign that veganism is here to stay is that the IDF now offers not only vegan food, but boots made of faux leather and berets made from fake wool.

And though, until recently, the trend was most obvious in secular Tel Aviv, interest in veganism is growing among the Orthodox, who draw inspiration and proofs from Torah to defend their position that halakha forbids causing animals to suffer. Chief among these is a Genesis passage in which God forbids man from severing the limbs of living creatures. The precept to avoid cruelty to animals—or tzaar baalei chayim—is also taken up in the Talmud in Tractate Shabbat, by Maimonides in his Mishneh Torah, and in the Shulchan Aruch, the most widely consulted code of Jewish law.

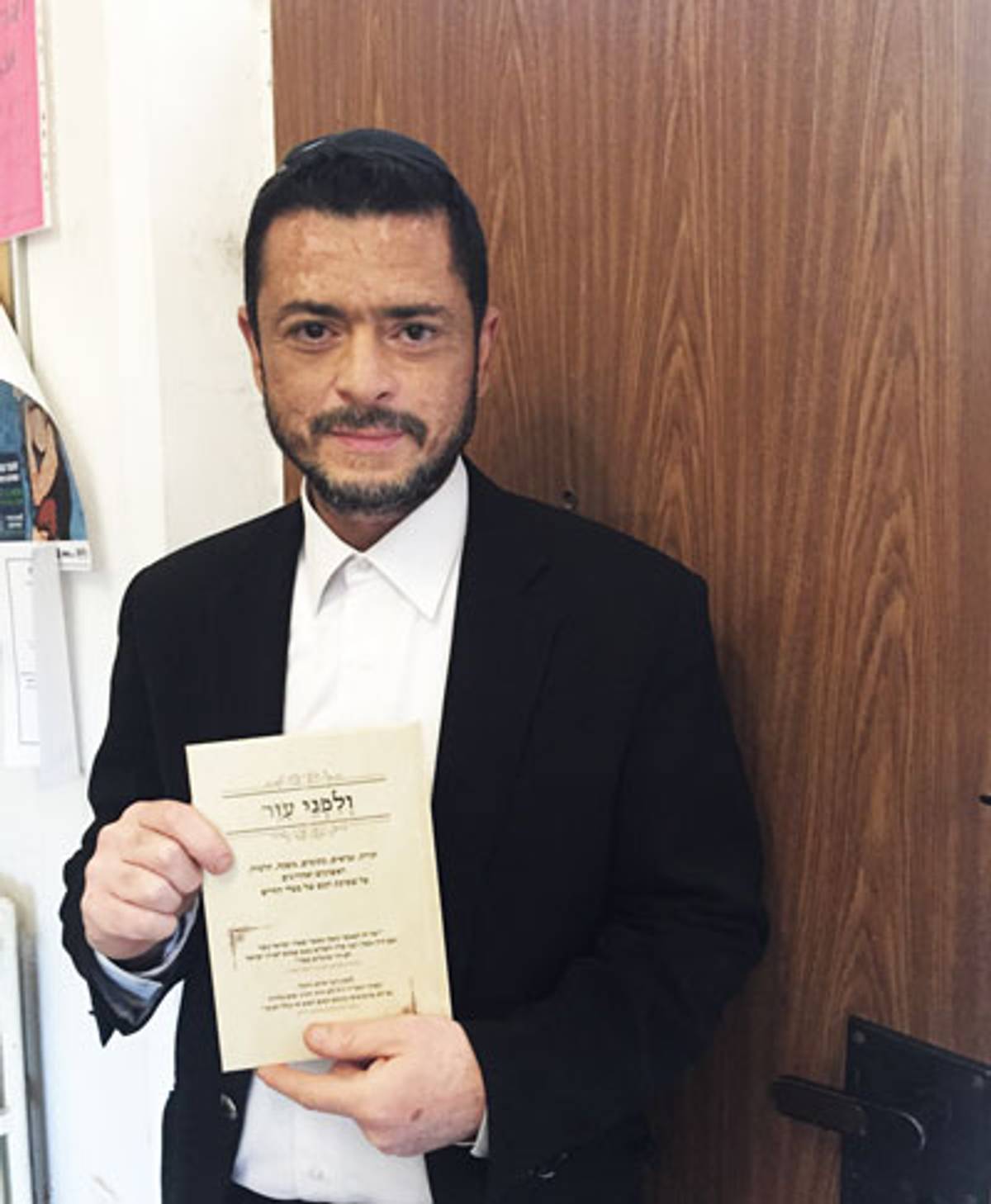

One of the most prominent religious voices belongs to Asa Keisar, a second-generation religious vegetarian, and now vegan, from the central town of Petah Tikva. He recently began giving lectures on veganism in yeshivas and synagogues around the country. Last month, he printed 11,000 booklets on the topic, which he and volunteers plan to distribute to yeshivas throughout Israel. They’ve also printed 10,000 posters promoting veganism to hang in ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods. “The Lecture Every Jew Has To Watch,” a video in which Keisar preaches the glory of veganism, has been viewed more than 200,000 times since it was posted six months ago.

“I do this because I believe in God,” Keisar told me on a recent afternoon in Jerusalem. “It’s a Torah idea, and that’s all. It is not about social consciousness.”

Growing up in Kiryat Ono, outside of Tel Aviv, Keisar, now 42, said he knew only one other vegetarian: his father, also a religious man.

“Back then, it was only my father who said meat was murder,” Keisar said.

In his lecture, Keisar takes his audience on a journey through what the Bible, the Talmud, and scholars have to say on meat consumption.

Interspersed in his yeshiva-lesson-like talk are graphic images showing, for example, a machine clipping the beaks of baby chickens off so they don’t peck each other in captivity. Keisar claims that this, and other practices, such as separating newborn calves from their mothers, violate the religious prohibition of causing harm to animals. He goes further, stating that people who buy or eat animal products are not only sinning themselves, but are causing others–those working in the food and agricultural sectors—to sin.

“It is like putting a stumbling block in front of a blind man,” he said of those who buy animal products. “There is halakha that it is forbidden by Torah to buy animal products. Clear cut,” he concludes.

Keisar is surprised at the number of people he encounters in yeshivas and synagogues who tell him that they are already vegan or vegetarian.“We are only at the beginning of this movement, it will grow and grow,” Keisar said.

Right now, it remains a grassroots effort, especially in Israel, where mostly lay people, not rabbis, embrace veganism. Rabbis who are themselves vegan are hesitant to be vocal about this lifestyle choice, said Ronen Lubitch, the Orthodox rabbi who organized last year’s Beit Hillel symposium.

“Even though it’s not always true, they see vegans as left-wing activists, anti-religious activists,” Lubitch said. “It also seems like it’s going against something very rooted in the tradition,” a tradition that revolves heavily around big holiday meals.

On his podcast, Gimpel said he was also advised to keep quiet about his new eating habits.

He didn’t take that counsel and has become an animal-rights activist, tying this issue into his overall agenda of religious Zionism and the connection to the land of Israel. A few months ago he became a partner in a farm run by two other families in Gush Etzion, the West Bank settlement bloc that includes the community where he lives, Neve Daniel. So far the farm includes a herd of 60 free-roaming sheep–all with names—hundreds of olive trees, grape vineyards, and chickens. There are plans to build a guesthouse so visitors can stay and learn about sustainable agriculture.

He is unsure whether he would want to eventually slaughter the sheep, or if he would eat these sheep or the meat of any animals treated in keeping with religious laws that prevent their suffering.

“I battle with that question a lot,” he said. Even if animals are raised and slaughtered humanely, he can’t help but think of the verse in Isaiah about the lion lying down with the lamb. It is here that Gimpel, Keisar, and Avraham Yitzhak Kook in his writing more than 100 years ago see a connection between avoiding meat consumption and messianic times. They see being vegan–or at least vegetarian—as a religious ideal.

“It’s not necessarily about the animals themselves,” Gimpel said on his podcast. “But rather about humanity coming to a higher sense of life, where we will not kill in order to eat.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Sara Toth Stub is a Jerusalem-based American journalist who has written for The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones Newswires, Associated Press, and other publications.