A Recipe for Connection

My mother, her cobbler, and a trailblazing cookbook author

My mother’s recipe for blueberry cobbler has been on our fridge for as long as I can remember. If I close my eyes I can picture her curling handwriting perfectly, the little flourish at the end of her c’s. I watched her bake that cobbler countless times, rarely measuring and almost never actually referencing the recipe.

After my mom died that cobbler recipe became even more important. A happy, easy memory that we could return to in the midst of all the grief and confusion. My sister embroidered it for myself and my brother, so we could hang it in our own kitchens. I smile every time I see it, because, just like my mother, I almost never actually look at the recipe when I’m making blueberry cobbler.

Recipes are important to my family. They’re links to past generations, to our heritage and religion. Our beloved recipes reflect the unique blend that makes up my family—the Judaism, the Lithuanian heritage, the more-than-a-dash of Kentucky Southern, all blended in a Midwestern casserole dish.

The act of cooking or baking for someone is, in my family, the ultimate act of love.

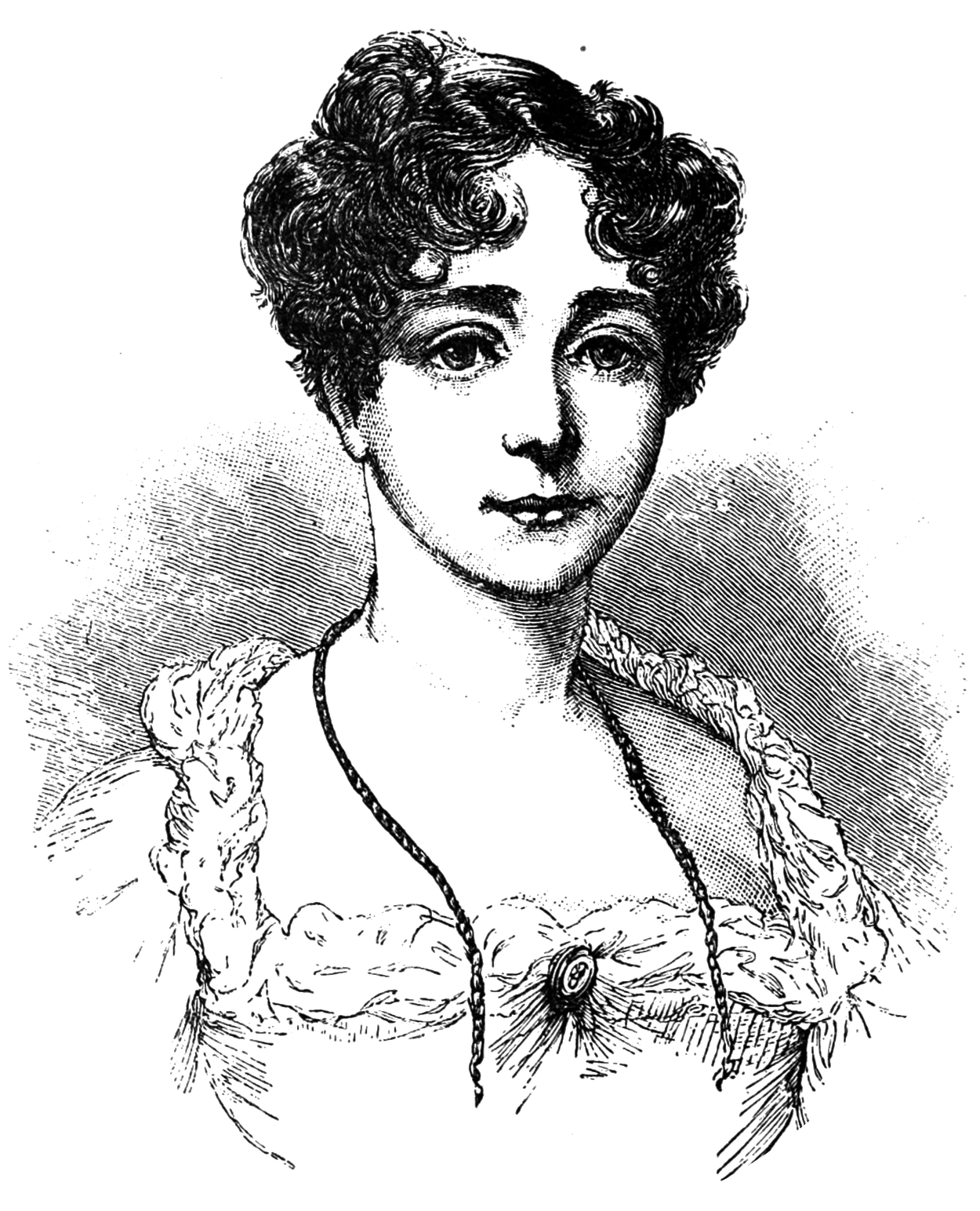

So I felt immediately emotional when I read about Judith Montefiore, the Jewish woman who wrote the first English-language cookbook, published in 1846.

Judith was born into a wealthy Jewish family and married into another. She and her husband, Moses, were passionate about their faith and education and they traveled and worked together to achieve their shared goals. But the cookbook, titled The Jewish Manual: or Practical Information in Jewish & Modern Cookery; with a Collection of Valuable Recipes and Hints Relating to the Toilette has always been associated with Judith alone.

In her introduction, Judith tells us she wrote it “to guide the young Jewish housekeeper in the luxury and economy of ‘The Table,’ on which so much of the pleasure of social intercourse depends.”

The cookbook, and the considerable amount of work it must have taken to get it together, felt instantly recognizable to me.

As a historian, I am always searching for those moments of recognition. While some encourage historians to maintain a healthy distance and detachment from their subjects, that is never the way I have approached history. I love finding stories that touch my heart and stick in my head.

It was my mother who encouraged me to study history in whatever way I wanted to, long before she probably even knew what she was doing. The part of my childhood not spent in the kitchen was often spent in a bookstore or a library, where my mom gave us completely free rein to read whatever we wanted. I chose historical fiction and romance, and while it’s not at all the literature she tended toward, she never once belittled my choices.

Judith’s story has stayed with me for years. I’ve debated all the ways to tell it. I started writing (and shelved) a romance novel inspired by her. The more I learned about her, the more I realized that the truth was, in this instance, better than fiction.

Judith married Moses Montefiore in 1812 and the couple were famously devoted to one another. They worked and traveled together, donating money to Jewish education everywhere they went. Judith even traveled to Israel five times!

In the end, I wanted to tell Judith’s story in its historical context. I wanted to tell the stories of lots of inspiring, fascinating, rule-breaking women from the Regency period so other people could have their moment of recognition. That’s why I included Mary Seacole, a British Jamaican nurse who worked during the Crimean War, and Anne Lister, a British lesbian landowner who lived openly with her wife during the 19th century, in my book Mad and Bad.

All the women in the book speak to me because of the exciting realities of their lives. They’re all examples of the true Regency—one that is even more fascinating because of its diversity of thought and appearance. But learning Judith’s story is the first time I felt a more personal connection to the time period I have been so immersed in for so long. Our shared love for our faith and food, and the belief that the latter can help educate about the former, felt like a sign I couldn’t ignore.

Of course I went looking for a cobbler(-esque) recipe in The Jewish Manual.

While there’s no exact recipe for cobbler, cobblers are really not all that dissimilar from pies (a mixture of baked fruit and crust of some kind), so I turned to Chapter IV, Pastry, and turned to page 106.

Under the heading “Fruit Tarts or Pies” Judith writes, “A fruit tart is so common a sweet that it is scarcely necessary to give any directions concerning it.”

I honestly burst out laughing when I read that. It’s so like my mother. It felt almost too perfect to find, here in this book full of recipes, Judith saying, you know how to make a cobbler, what do you need me for?

I do need Judith. I need all Jewish women throughout history. Seeing myself, my mother, and generations of Jewish women in that (not a) recipe made me feel connected to history in an entirely new way, even after studying it my whole life.

And at the risk of sounding corny, there is something magical in that.

Bea Koch is the author of Mad and Bad: Real Heroines of the Regency and the co-owner of the Ripped Bodice, a romance-focused bookstore in Culver City, Calif.