Tel Aviv’s Original Culinary Scene

A century before the city became the trendy ‘bubble’ that it is today, pioneering restaurants and cafes set a cosmopolitan tone

On a rainy day in January 1939, thousands of Tel Avivians gathered at the seashore to watch a local landmark sink into the Mediterranean. It is odd to talk about landmarks in a city barely 20 years old, but Casino Galey Aviv certainly was one.

Its story started in 1920, when one Solomon Kraznovsky arrived in Tel Aviv with deep pockets and an ambition to give his new hometown a modicum of cosmopolitan chic. He persuaded Meir Dizengoff, the first mayor of Tel Aviv, to grant him permission to build and operate a seaside casino. His only request was that there would be a proper access road. This is why Allenby Street, the main drag in those days, takes a sharp turn west at its northernmost point, leading up to the beach. Construction began in 1921. An ornate, rather small three-story building was erected on concrete pillars sunk into the sand. On the first floor there was a reception hall; the second floor housed a restaurant and a winter garden; and on the top floor, there was a roof cafe. The grand opening in the summer of 1922 was a momentous event in the city’s short history. Despite its name, not a single game of chance was played there (the permit for gambling was never obtained), but the casino did brisk business entertaining Tel Aviv’s elite.

Troubles started when the winter came. The sea level rose, flooding the ground floor, and gusty winds ripped off doors and smashed windowpanes. The place closed down, and Kraznovsky, whose funds turned out to be skimpier than he cared to disclose to the authorities, went bankrupt. Moshe Abarbanell and Mordechai Weisser, a pair of successful businessmen and founders of Eden, the first cinema in Tel Aviv, took over the casino. Undeterred by weather conditions, they spent a fortune revamping the place. Fountains spitting water and “cold fire” were installed at the entrance, a huge new bar dominated the lower floor, and a small army of dinner-jacket-clad waiters served the clients “in the best European tradition.” To maintain an exclusive atmosphere (and boost profits) the owners decided to charge an entrance fee. “If we don’t apply this measure,” they wrote in the petition to the municipality, “the place will be swamped with families littering the floor with sunflower seeds and tending to squealing children.”

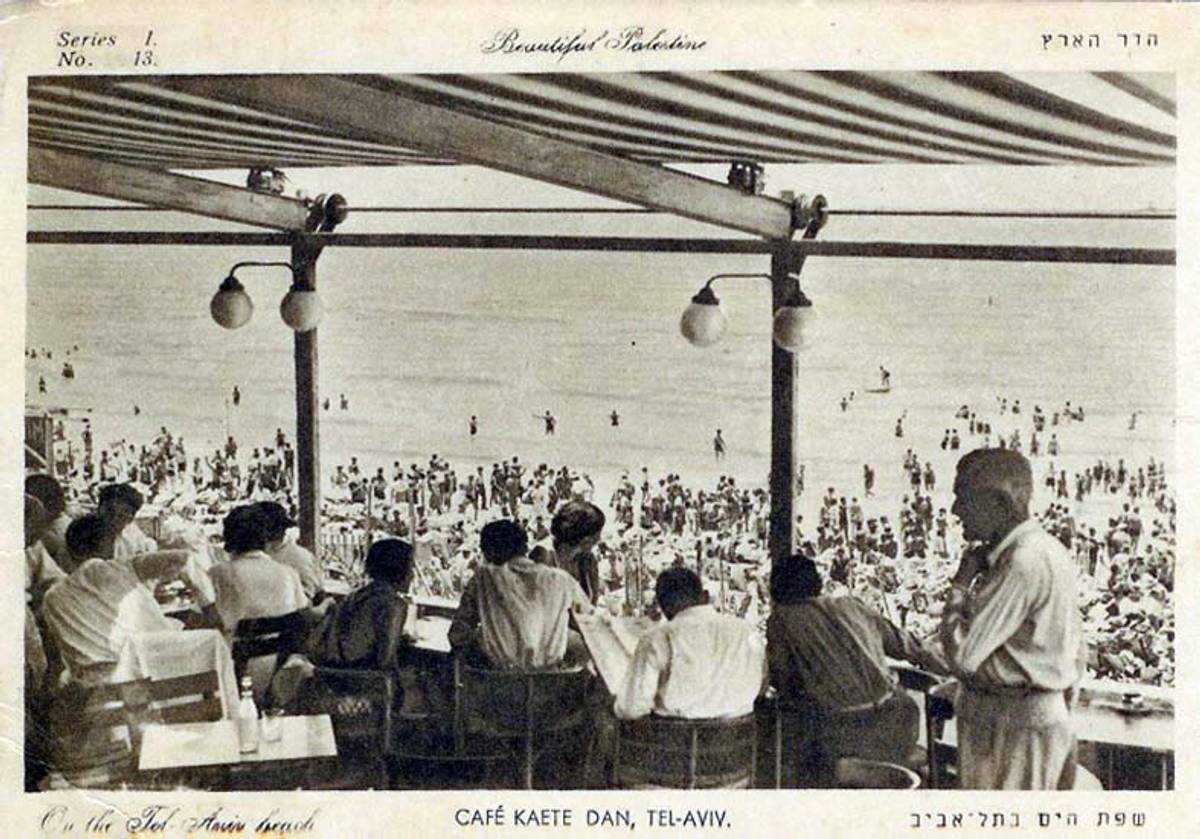

Casino Galey Aviv was famous for its parties and banquets and was regularly written up in local newspapers. Curiously, there is hardly any mention of what was actually served there. According to one source, it was the first restaurant in Palestine to serve steak and french fries, while other sources mention the decidedly inelegant Hungarian cholent. Whatever the truth, the main draw of the place was not the food but the location. Abraham Cahan, the legendary editor of The Forward, visited the casino in 1925 and was impressed. He called it “a balcony at the edge of the sea” and compared it to Rockaway, Arverne, or Edgemere—seaside communities in Queens, New York. He appreciated how cool it was in the afternoon “when the sun scorches all around” and even liked the orchestra (“not big but good”).

The casino survived until 1936, changing ownership a few times, but with each winter falling more into a state of disrepair. In 1939, the municipality decided to rescue the building from its misery. The winds of war were already blowing and there was a fear that a building conspicuously jutting into the sea would be too visible for the bombers.

The demise of Casino Galey Aviv in 1939 symbolically marked an end of a fascinating and largely untold chapter in the history of Tel Aviv, one that presaged the culinary and urban renaissance of the city that would come some 60 years later.

Tel Aviv today is often described as “the bubble” because of its defiant insistence on hedonism, secularity, and liberalism. Apparently, this bubble has been around for more than a century. From its inception in 1909, Tel Aviv was unlike any other town or settlement in Palestine. The early Zionist ethos spoke of farming, making the wilderness bloom, and creating a new Jew: proud, strong, and connected to the land.

Anything reeking of the “sorrowful diaspora” or bourgeois lifestyle was denounced. Tel Aviv’s agenda was different: The founders of “The First Hebrew City” imagined a town as beautiful and lively as Odessa, Warsaw, or Vienna, with buzzing cultural life, leafy boulevards, and a seaside resort vibe. They did not want to break away from the past, but to improve on it. Accordingly, new immigrants drawn to Tel Aviv were mostly secular city dwellers. Many had money and an entrepreneurial streak and were not averse to creature comforts. By the mid-1920s, when the city’s population was around 30,000, there were already over 100 eating and drinking establishments—from simple, family-owned workers’ kitchens to kiosks offering drinks and refreshments, to cafes and nightclubs, like Casino Galey Aviv. One such place was Hotel Palatin on Nahalat Binyamin Street. Prices there were even higher than in the casino, the ambience more snobbish, and the afternoon dances were notorious for bringing together pretty Tel Avivian girls and British officers.

Tel Aviv’s first food market, known today as the Carmel Market, opened in 1920, operated by several families of formerly prosperous Russian Jews. Seven years earlier, these families had purchased some land in the newly established city. They did so for philanthropic reasons, never intending to immigrate to Palestine. But in 1917 the October Revolution broke out and the families fled Russia, leaving their fortunes behind. The land they had purchased in Tel Aviv was their only source of livelihood and after a battle with the municipality, they were allowed to found and operate a food market on their property. Carmel Market offered basic goods, fruits and vegetables from the neighboring villages, and freshly slaughtered chickens and geese.

The latter evolved into one of the more famous delicacies of the time. The king and queen of the goose business in Tel Aviv were Baruch Chaim Fenigstein and his wife, Surele. The couple emigrated from Warsaw in the early 20th century, settled in Jaffa, and then moved with their children to Tel Aviv, where they opened up a family restaurant serving fresh beer and goose—rubbed with a secret spice mix and roasted whole in the Fenigsteins’ private bathroom. Rabbi Fenigstein (he was not really a rabbi, but was called so because he was an observant Jew with a long white beard) and his wife were talented and creative cooks and the restaurant was always packed. One of their specialties was salad dressed with a sweet-tart syrup that the rabbi made himself by boiling down prickly pears.

Tel Aviv’s culinary scene exploded in the 1930s with the arrival of German-speaking immigrants fleeing the Nazi regime. The city’s population leaped from about 30,000 in 1924 to almost 160,000 in 1936. The newcomers were mostly affluent, fiercely proud of their Germanic heritage, and intent on maintaining the lifestyle they were accustomed to in the Old Country. In a span of a few short years, they completely transformed Tel Avivian architecture, cultural life, nightlife, and gastronomy. Dozens of restaurants serving Wiener schnitzel and other Central European specialties sprang up around city, but the hallmark of the Germanic exodus to Tel Aviv were pastry shops and cafes. Many opened on Ben Yehuda Street, sarcastically referred to as Ben Yehuda Strasse by Tel Avivians. “The streets of Tel Aviv have been transformed by Herr Hitler,” wrote The Palestine Post in 1933. “In fact, they are no longer streets. The have become Strassen. Tel Aviv can change her color as quickly as a chameleon, responding to the whims of the Russian czar, a brown-shirted chancellor, or even Wall Street quotations. Once little Odessa, then little Warsaw, now little Berlin.”

Two of the most famous cafes of the time—Ginati and Noga—were situated right across from each other. Each boasted a huge open garden that could seat up to 800 diners, and an orchestra that played during the summer months; both served homemade cakes, light meals, coffee and tea; both had German menus, German-speaking waiters, and mostly German-speaking patrons. The waiters were notorious for their haughty service, especially toward those who addressed them in Hebrew. The women showed up in silk gowns in summer and their best furs in winter, and the men never parted with their jackets even at the height of summer.

While 800 diners is a very impressive number, Noga and Ginati weren’t the largest eating establishments in Tel Aviv. That title went to Beit Brenner. Situated in the headquarters of The Hebrew Trade Union (Histadrut Hapoalim), this cooperative eatery fed about 2,500 diners a day, making it the biggest restaurant in Palestine. In the summer the number would leap to 3,000. The reason: “Thousands of people trek into Tel Aviv from the outlying rural settlements to bathe in the sea and many of the Tel Aviv housewives declare an unofficial ‘strike’ during the hot weather and take a holiday from the kitchen,” explained an article published in 1937 in The Palestine Post. The hit of the summer menu was fruit soup, cooked by “a fruit soup specialist who does nothing else but prepare this delicacy.” German influence was apparent there as well: “Lately, Palestine has become ‘cake conscious’ … now the kitchen employs a Belgian baker who knows all the secrets of fluffy crusts and creamy fillings.” Beit Brenner was not a place for leisurely meals: “People have been schooled to eat their meal and leave.”

The kind of folks who frequented Beit Brenner and other communal restaurants did not wear silk gowns or dinner jackets. They were clerks, builders, and other members of the working class. Many lived in rented rooms with no kitchen of their own. They depended on eating out so much that when restaurant workers went on strike in 1935 it caused a “small panic” (to quote The Palestine Post), and the authorities quickly settled the dispute. Other high-profile conflicts involved lockdown on Shabbat (a compromise was reached, which most restaurateurs ignored), closing hours (neighbors complained about unbearable noise that went on well after midnight), and permission to put up tables on the sidewalk (cafes and restaurants invaded the sidewalks even if the license was refused). Sound like Tel Aviv today?

Absolutely.

Cramped living conditions and hot weather drew Tel Avivians out to the streets, the parks, and the seaside. During summer, the beaches and the promenade were packed. The masses sipped espresso, drank soda (locally called gazoz) or nibbled piping hot corn on the cob, which vendors fished from huge tubs filled with boiling water. The favorite summer treat was ice cream, a novelty that descended upon Tel Aviv in the mid 1930s (another contribution of German-speaking immigrants) and caused a sensation. Over a dozen ice cream parlors popped up around the city. Electric ice cream makers were prominently placed at the windows to attract customers and many places offered a dozen flavors of freshly made ice cream.

Last but not least were the literary cafes. Every famous (and not so famous) writer or poet had a cafe of choice where he would come on a daily basis to write, muse, and meet fellow writers and fans. More social clubs than eateries, these places evolved into one of the symbols of Tel Aviv, and their stories deserve an article of their own.

Toward the end of the 1930s, the party that was Tel Aviv started to wind down. WWII, the Holocaust, Israel’s War of Independence, and the huge waves of immigration that brought about deep economic crises in the early 1950s gradually robbed the city of its chic and joie de vivre. Hastily built drab housing projects dominated the cityscape, putting to shame exquisite Bauhaus buildings that by that time looked crumbling and dilapidated. What remained of the restaurant scene was basic and unexciting. The young city aged quickly and not gracefully. But then, toward the end of the century, things miraculously started to turn around—culturally, architecturally, and gastronomically. Tel Aviv today is again a gorgeous cosmopolitan city that dances, eats and drinks around the clock, and does so with its unique blend of laid-backness and style. The bubble remains firmly in place, and even the pandemic didn’t manage to take away Tel Avivians’ unrelenting strife for normalcy and fun.

(Author’s note: A big thank you to Shula Widrich, a scholar of Tel Aviv history, who helped me with the research for this article.)

Janna Gur is a Tel Aviv-based writer and journalist. She is the author of The Book of New Israeli Food, Jewish Soul Food from Minsk and Marrakesh, and Shuk (with Einat Admony).