What Is ‘Jewish Food’?

It is profoundly global, deeply regional, and eminently adaptable. And it is often not exclusively Jewish.

As a Jewish cookbook author who leads culinary workshops around the country, I get a fair number of repeat questions from audience members. “Can you help me track down my grandmother’s lost gefilte fish recipe?” is a common one. “Can I leave out the nuts (or flour, milk, eggplant, etc.) in the dish you are making?” is another. But there is one question that comes up more than most: “How exactly do you define Jewish food?”

It is a great question, and also a really complicated one. I love it because it indicates to me that people are thinking both critically and broadly about what it means to “eat Jewish.” Jewish cuisine is often reduced to a short list of latkes, pastrami, matzo ball soup, and other Eastern European hits. It is also regarded as immutable—a fixed thing, passed down from generation to generation since time immemorial. (And woe to the cook who takes creative license with Bubbe’s kugel recipe.) But in reality Jews have moved around a lot throughout history—by choice and by force—and so have lived and cooked just about everywhere. The Jewish merchants who once traded along the Silk Road and elsewhere, meanwhile, swapped not only spices and other goods but also ideas. As a result, Jewish cuisine is at once profoundly global, deeply regional, and eminently adaptable.

“For thousands of years, wherever Jews lived they created their own micro-cuisines based on the kosher laws and the local terroir and food traditions,” said Naama Shefi, founder of the Jewish Food Society. In some cases, they adapted a local dish to fit their dietary or ritual needs. Hungarian Jews, for example, serve chicken paprikash without the sour cream most other Hungarians stir into the sauce. In others cases, a traditional recipe was changed to incorporate regional flavors. Take the slow-cooked Sabbath stew called cholent by Ashkenazi Jews and hamin or dafina in Sephardi communities. “It has endless variations, which are based on local ingredients—fragrant rice and chicken in Iraq, fatty beef, potatoes, and beans in Poland, and chickpeas, cracked wheat, and turmeric in Morocco,” Shefi said.

Cookbook author Flower Silliman grew up in Kolkata in the 1930s, where the Jewish community primarily consisted of immigrants from Iraq and Syria. As a result, Kolkata’s Jewish cuisine is a delicious mashup of Baghdadi dishes filtered through a prism of ginger, coconut milk, chiles, and other Indian ingredients. “We had the dishes from the past and we saw what our neighbors were making and what looked good, and we invented a new dish,” she said. “That is how recipes evolve.”

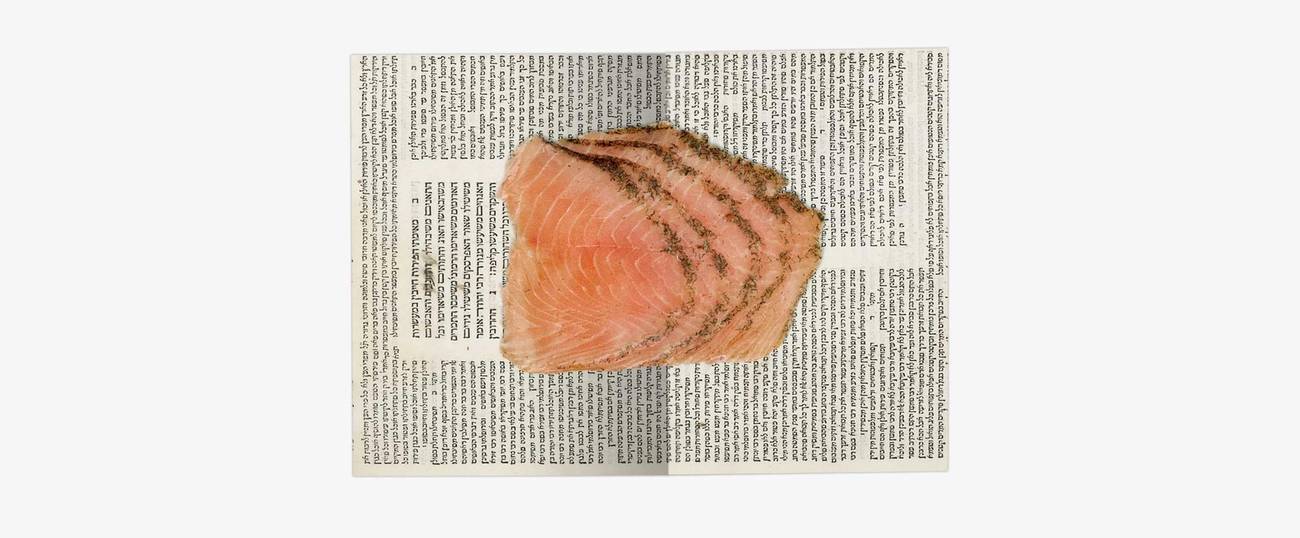

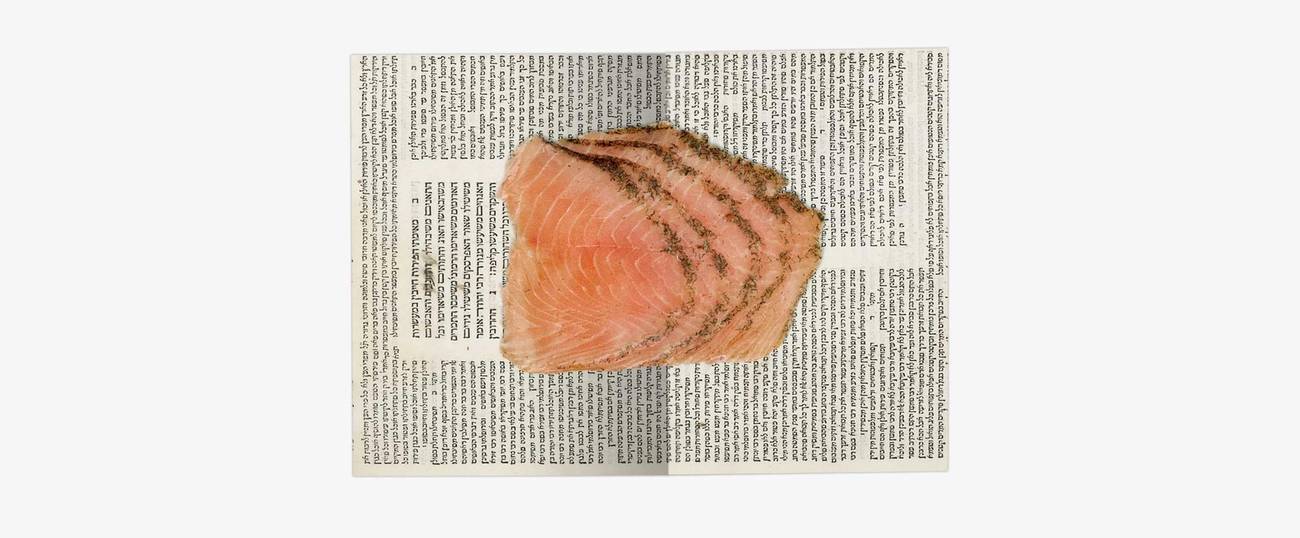

This evolution continues, as evidenced in dishes like gefilte fish a la Veracruzana, which was developed by Ashkenazi communities who settled in Mexico in the early and mid 20th-century. They took the classic Jewish fish appetizer and added tomato, oregano, olives, and other Spanish-inflected regional flavors. And then there are Nutella-filled hamantaschen, a quickly-growing favorite in America, thanks to this country’s infatuation with the Italian chocolate-hazelnut spread. Purists might call this modern creation an abomination, but others would swear their Purim celebration isn’t complete without it. Either way, the cookies serve as a sweet reminder that Jewish cuisine is as expansive as our imaginations.

And yet, it is this global nature that makes a Jewish food canon so difficult to define. Historically, kashrut has provided a natural perimeter for Jewish food. Regardless of whether home cooks were feeding their families in Bulgaria, England, or Tunisia, the kosher laws served as a constant—a sacred through-line. Even today, when plenty of Jews eat decidedly non-kosher diets, it would be difficult to make a case that BLTs, cheesy lasagna made with meat sauce, or clam chowder are “Jewish.” But beyond that, what are the boundaries?

My own definition, honed over the years of fumbling to answer the question at cooking demonstrations, is that Jewish cuisine includes any dish that holds meaningful cultural, historical, or ritual significance to Jewish communities. But—and this is an important but—to identify a dish as Jewish does not claim it as exclusively Jewish.

A handful of foods like charoset and matzo are so closely tied to a particular holiday practice that it is safe to assume they have a distinctly Jewish pedigree. And in some cases, like with eggplant caponata in Sicily, Jews were likely the first to develop and eat a dish that eventually went on to have mainstream appeal.

But most of the foods thought of as Jewish actually hold dual identities. In America, things like beet borscht, sauerkraut, stuffed cabbage, pierogi, and apple strudel are typically associated with the Jewish community because Central and Eastern European Jewish immigrants helped popularize them here. But in their home countries, everyone enjoys variations of these foods. Persian Jews, meanwhile, swoon over the same crunchy, tahdig-capped rice dishes as their non-Jewish Iranian neighbors.

In recent years, criticism has mounted against those who define Middle Eastern and North African foods like falafel, hummus, and shakshuka as Israeli (and therefore Jewish by extension). The relatively young, politically supercharged country is often accused of cultural and culinary appropriation of Arabic cuisine. Of course, Israel is filled with remarkable cultural diversity, including Arab communities living within the country, and Jews hailing from Arab countries who arguably have their own longstanding relationships with Levantine cooking. The problem comes back to those making claims of exclusivity. Yes, falafel, hummus, and the like are “Israeli” because these dishes are fundamental to the people who live there. But by no means are they Israel’s alone.

When Israeli chef Meir Adoni recently opened Nur in New York City, his first restaurant in America, he was adamant about positioning his menu as modern Middle Eastern. Adoni said customers sometimes ask why he doesn’t call Nur an Israeli restaurant. His answer is that Israel is only part of the equation. “I want to give honor to the people who this cuisine belongs to,” he said. “I am really proud that I am Israeli and Jewish, but I want to make sure I am telling the right story.” Adoni’s nuance and sensitivity toward this matter is refreshing, and not necessarily common practice.

Ultimately, borrowing is at the heart of all Jewish cuisine—and Jewish home cooks have historically played the role of adapters and transmitters of recipes, rather than innovators. But this is something to celebrate, not apologize for. Jewish cuisine’s endless geographical crisscrossing and constant evolutions certainly make it more difficult to define than a cuisine that developed within a single border. But they are also what make Jewish food so endlessly fascinating, so culturally vital and, most importantly, so memorably delicious.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.