American Blood Libel

It did happen here

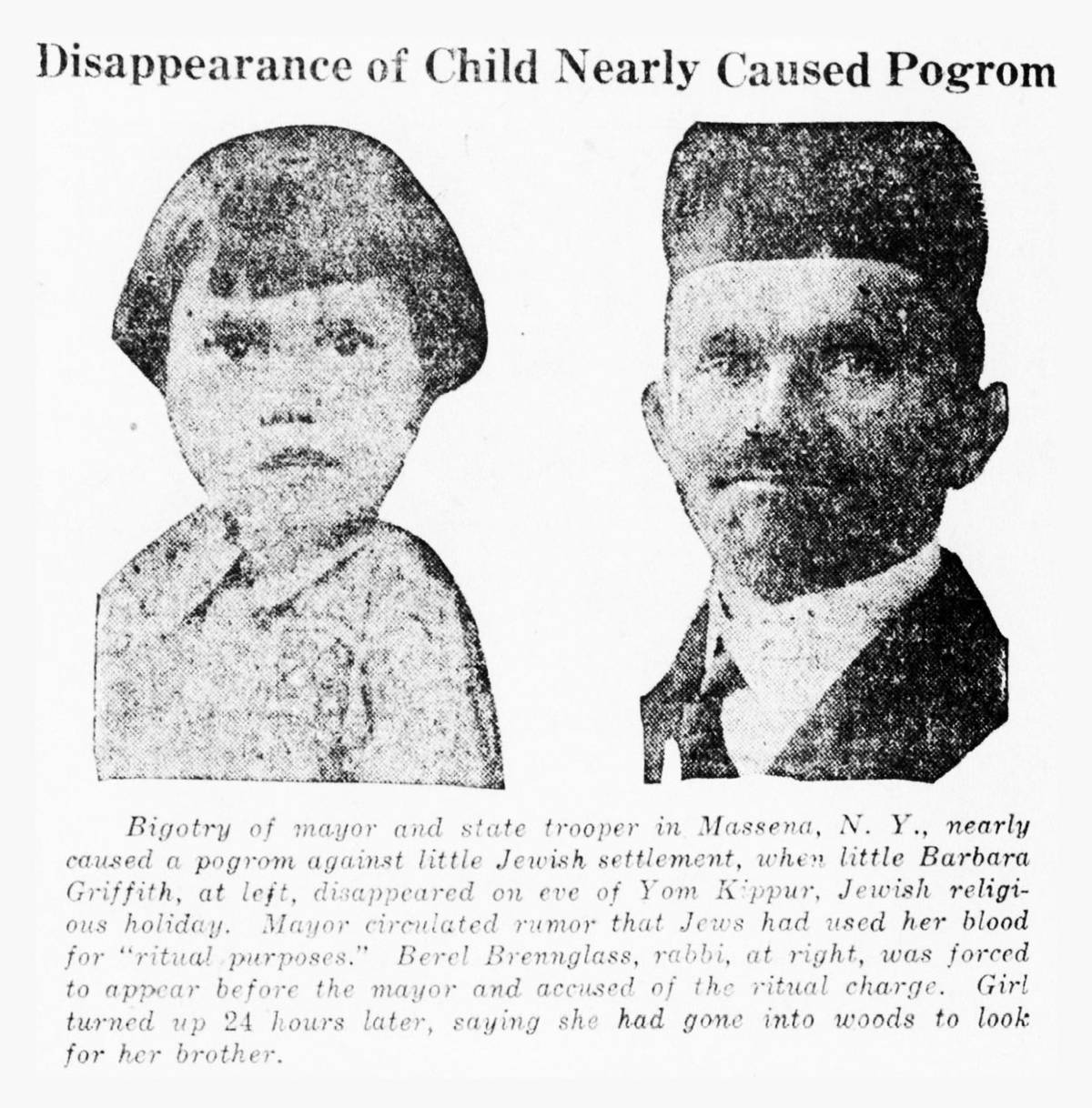

Massena is an undistinguished small town with a population of about 10,000 in upstate New York. But in the fall of 1928, an incident occurred that brought the town national newspaper coverage and frightened Jews across America. On Sept. 22, a few days before Yom Kippur, Barbara Griffiths, a 4-year-old girl, wandered into the woods surrounding the village and disappeared. When she did not return home hours later, her frantic parents contacted the mayor and the local police. Thus began the tale of the only blood libel accusation against Jews in American history.

The blood libel is the accusation that Jews murdered Christian children at Passover to use their blood for making matzo. The charge first appeared in Norwich, England, in 1144, and from then on it popped up repeatedly throughout European history. It even appears in Chaucer’s “The Prioress’s Tale,” which is included in his Canterbury Tales. The myth never received any official backing from the popes, but that did not prevent local Catholic parish priests from referring to it on Good Friday and in Easter services.

1920s America was rife with such antisemitic narratives. These feelings were undoubtedly stoked by Henry Ford’s libelous series, “The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem,” which was first published in his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, from 1920 to 1922. The newspaper had a wider circulation than The New York Times. The articles were also collected and republished in pamphlets by the same title. Everyone who bought a Ford automobile received a copy. He was the most popular American, and millions of Americans bought his automobiles, and they believed and trusted him.

Thus it was easy for Protestant Americans, unnerved by the massive immigration and perceived social threat of Catholics and Jews into the United States during the early 20th century, to believe what Ford wrote. The Ku Klux Klan, which had been dormant, subsequently attracted large numbers of disaffected Protestants and reached a nationwide membership of 3 million by 1925. The Klansman’s creed concluded with the pledge, “I am a native-born American citizen and I believe my rights in this country superior to those of foreigners.” A contemporary observer remembered that Massena was awash in flyers advertising Klan meetings and hundreds of locals showed up at them.

Antisemitic attitudes were also reflected in the passage of restrictive national immigration laws in 1921, especially in the 1924 act severely limiting immigration from Eastern Europe (where most Jewish immigrants hailed from.) Magazines catering to Protestant readers consistently warned about America becoming the “dumping ground” for Europe’s refuse. The 1924 Immigration Act, and its openly discriminatory quotas, also catered to this audience, with disastrous consequences for Jews. Most of the would-be immigrants remained in Eastern Europe and perished in the Holocaust.

The presidential election of 1928 manifested these trends and was especially contentious. It pitted Alfred E. Smith, the Democratic governor of New York and a Roman Catholic who was aligned with urban immigrants, against Herbert Hoover, a Protestant from the Midwest of the Republican Party and the embodiment of old-stock America. To his supporters, who were primarily white Protestants from England and northern Europe, Hoover represented their traditional understanding of who Americans should be.

The 1928 campaign was also infused with religious animosity. Al Smith was the first Catholic to ever run for the presidency, which was upsetting enough. But some of his closest advisers were Jews, and everybody knew it. This added to the Protestant unease, and during the campaign, antisemitic sentiments were publicly expressed by Smith’s opponents. This election brought together all these negative attitudes that were percolating in America throughout the 1920s, setting the stage for the events in Massena.

Within hours of the little girl’s disappearance, the authorities assumed they had a murder case on their hands. After a long search by townspeople and the state police, a rumor began circulating that the girl had been kidnapped and murdered by the town’s Jews for a religious ritual associated with their impending Yom Kippur holiday. In 1928, the town contained 20 Jewish families.

The large Alcoa plant near Massena attracted immigrant workers from the parts of Europe and Canada where antisemitic attitudes were common—and where the blood libel narrative was frequently accepted. It is probable that many of these immigrants believed that the Jews indeed murdered children for their religious rituals.

Corporal H.M. McCann, a state trooper, showed up late that night with two other troopers and forced the Jewish clothing store owner to open his store so it could be searched for the little girl’s body. A local Jewish boy, Jacob Shaulkin, came forward and had what was later called a “rambling conversation” with the troopers. The girl, he said, “could be anywhere.” The boy was sent home and his testimony disregarded because the troopers believed he had a “low mentality.” Nonetheless, the troopers were left with uneasy feelings about what they heard.

The next day, the state police summoned members of the tiny Jewish community for interrogation. They first questioned Morris Goldberg, a local Jew with minimal knowledge of the Jewish religion and traditions. Goldberg’s imprecise answers left the police with the impression that there might be some truth to the rumor that the Jewish faith did involve blood sacrifice.

The next morning, another local Jew was brought to the investigators and asked about the alleged custom. He said he knew nothing about it and told the police to talk to the town’s rabbi, Berel Brennglass, who headed the town’s Adath Israel synagogue. Brennglass was summoned to police headquarters, allegedly at the behest of Massena’s mayor, Gilbert Hawes.

Trooper McCann interrogated Rabbi Brennglass for more than an hour. McCann asked the rabbi, “Can you give any information as to whether your people in the old country offer human sacrifices?” Brennglass, appalled by his questions, told the police and Mayor Hawes, who was also present, that they should be ashamed of themselves. “I am dreadfully surprised,” he said, “to hear such a foolish, ridiculous, and contemptible question from you.”

Meanwhile, as the rabbi was being questioned, little Barbara Griffiths was found. She had become tired while looking for her brother and fell asleep in some tall grass. Except for some small tears in her clothing, she was unharmed. The local newspaper The Observer noted that “Her clothing was somewhat torn and she was pretty tired and hungry, but otherwise none the worse for her experience.”

But the mob of townspeople was still unaware that Griffiths had been found safe. They confronted the rabbi as he left town hall, blaming him for killing and sacrificing her. Even after her discovery became public, many of these people still believed that she had been abducted and was only released by Jewish leaders after the discovery of the plot. They called for a boycott of Jewish businesses, but no boycotts occurred.

On the night of his interrogation, Rabbi Brennglass spoke to his congregation at Kol Nidre services. “We must forever remind ourselves that this happened in America, not tsarist Russia among people we have come to regard as our friends. We must tell the world this story, so it will never happen again.”

By the time Barbara was located, the claim of blood libel in Massena had received national coverage in the press. The New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Atlanta Constitution, and Los Angeles Times, as well as numerous small papers, all published stories about the incident.

The 1928 accusation had frightened and infuriated the Jews of Massena because they did not know how to defend themselves against the charge. Many older Jews remembered with trepidation the 1915 case where a Jew, Leo Frank, was tried and lynched on spurious grounds of gentile defilement—accused of killing a young girl for ritual purposes.

Two days after Barbara’s reappearance, with news stories circulating, a contingent of officials including Mayor Hawes, state trooper McCann, McCann’s boss, and the town attorney showed up at Massena’s synagogue to offer their apology in person. The apology was not accepted. The congregation’s leaders felt the matter was now in the hands of the national Jewish leaders whom they had alerted—Louis Marshall, head of the American Jewish Committee, and Dr. Stephen Wise, of the American Jewish Congress.

Marshall was born in Syracuse, New York, to a family of German Jewish immigrants. He graduated from Columbia University Law School in 1877 and became a partner in the law firm of Guggenheimer & Untermeyer. His legal career was marked by his defense of the constitutional rights of minorities. Rabbi Stephen Wise was a Reform rabbi and Zionist leader. He served two terms as president of the Zionist Organization of America.

The two men pursued a vigorous course of action, with Marshall addressing a letter to the mayor, roundly condemning him for failing to put down the “abominable superstition ... which might have resulted in one of those many calamities recorded on the bloody pages of medieval, and even modern, European history.” Wise, acting on behalf of the American Jewish Congress, had already also demanded formal apologies. Gov. Al Smith denounced the mayor; the commander of the Jewish War Veterans threatened to institute a suit; newspapers expressed editorial horror; the Permanent Commission on Better Understanding Between Christians and Jews in America appealed to American citizens to prevent the spread of the blood libel.

Mayor Hawes then wrote a personal letter to Dr. Wise expressing regret if he had caused offense to the Jewish people. Wise found it “too vague to constitute an apology.” At Wise’s urging, Gov. Smith, at the time the Democratic nominee for president, convened a hearing in Albany, New York, to investigate the investigators on how they had come to pursue what Smith called the “absurd” claim of ritual murder.

At the end of the hearing on Oct. 4, 1928, Hawes finally issued a formal written apology that satisfied Wise. Hawes admitted he had committed “a serious error of judgment” and expressed “clearly and unequivocally” his “deep and sincere regret” that he had “seemed to lend countenance, even for a moment, to what I ought to have known to be a cruel libel imputing human sacrifice as a practice now or at any time in the history of the Jewish people. Far from giving hospitable ear to the suggestion, I should have repelled it with indignation and advised the state trooper to desist from his intention of making an inquiry of the respected rabbi of the Jewish community of Massena concerning a rumor so monstrous and fantastic.”

Corporal McCann issued his own written apology, addressed to Rabbi Brennglass, the same day. He wrote that he was “very, very sorry for my part in the incident at Massena” and now realized “how wrong it was of me to request you come to the police station at Massena to be questioned concerning a rumor which I should have known to be absolutely false.” Both these apologies were dictated by Rabbi Stephen Wise.

Although there were other allegations of blood libel in America, the happenings in Massena are unique because Mayor Hawes, the town’s top public official, gave the rumor credence, authorizing the police to investigate it and interrogate the town’s rabbi. While Hawes was likely not immune from the common prejudices against Jews of that era, there is no evidence that prior to this incident he harbored any deep-seated anti-Jewish sentiment. He served with Jewish businessmen on the boards of the Massena Chamber of Commerce and the Massena Savings and Loan Bank. He defended himself during the scandal by forcefully stating that “I have daily business intercourse with Jews and am on friendly terms with them.” He also claimed that his “best friends growing up “were mostly Jewish boys” whom he met when he lived in Newton, Boston, Brooklyn, and New Rochelle. And the Jews in Massena themselves had previously never felt any prejudice from him.

Even though Barbara Griffiths was found in the woods that afternoon a mile from her home, and told authorities she had become lost during her walk and slept in the forest, some citizens of Massena still believed for years that she had been kidnapped by the Jews. They attributed her safe return to the discovery of the Jewish plot.

For her part, Barbara had a nice life after the ruckus. Her family remained in the north country following her jaunt into the woods. She graduated from Massena High School, and in 1947 from St. Lawrence University in Canton with a degree in physics (during a time when not many women studied science.) In 1947, she married John F. Klemens of Brooklyn, in Massena.

Barbara had many passions, ranging from her love of the outdoors and St. Lawrence University’s hockey team. She received a number of awards for her knitting skills. For 50 years she was the proprietor of the Yarn Shop in Canton and was a committed evening bridge player. She also created her own archives of press clippings about the libel incident. Although she did not have any memories of the incident, she did remember many things that happened afterward. She died in August 2019 at the age of 94.

Robert Rockaway is professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University, and the author of But He Was Good to His Mother: The Lives and Crimes of Jewish Gangsters.