The Paris Commune at 150

France’s second revolutionary sequel was a failure. But it looks better than its successors.

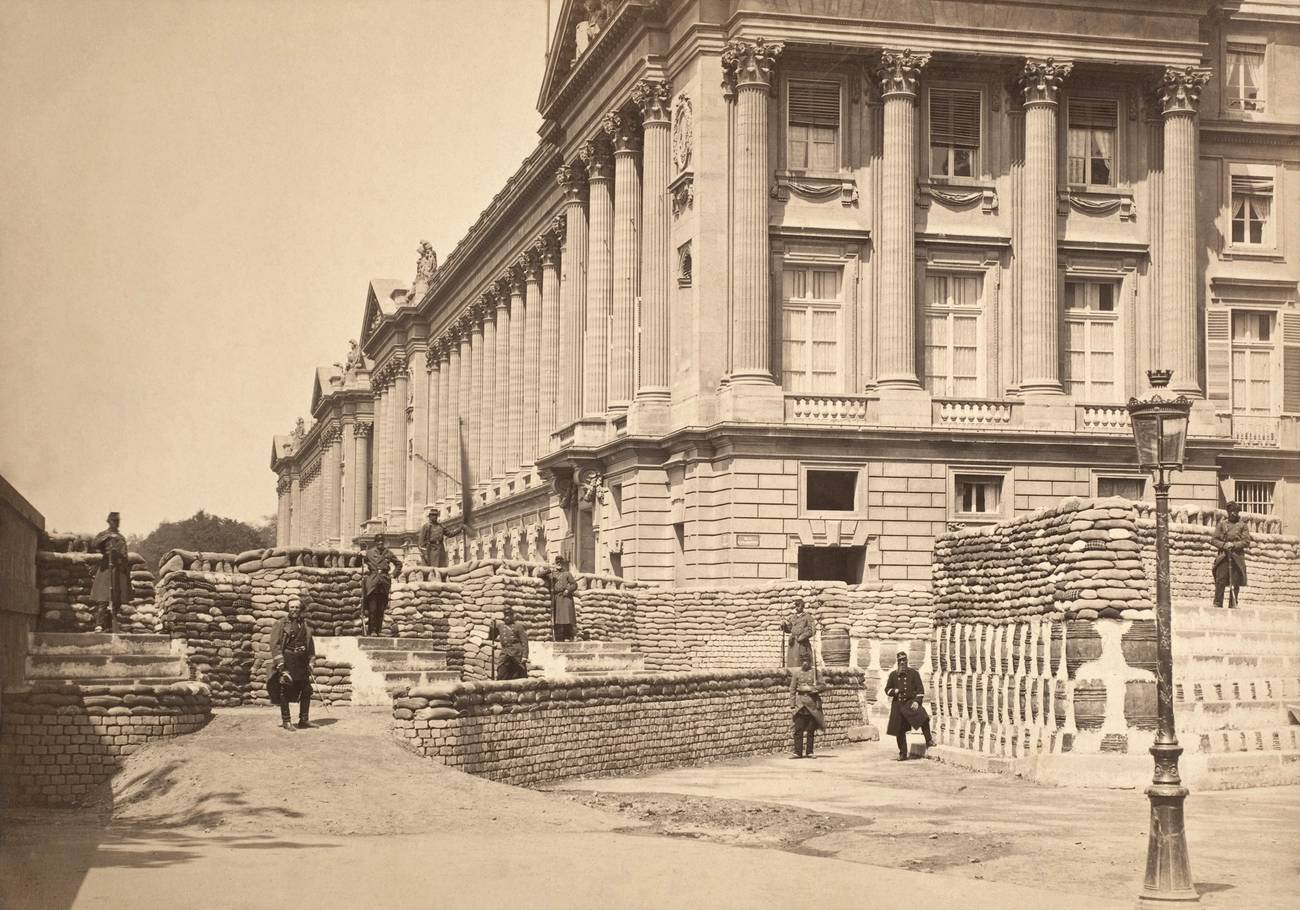

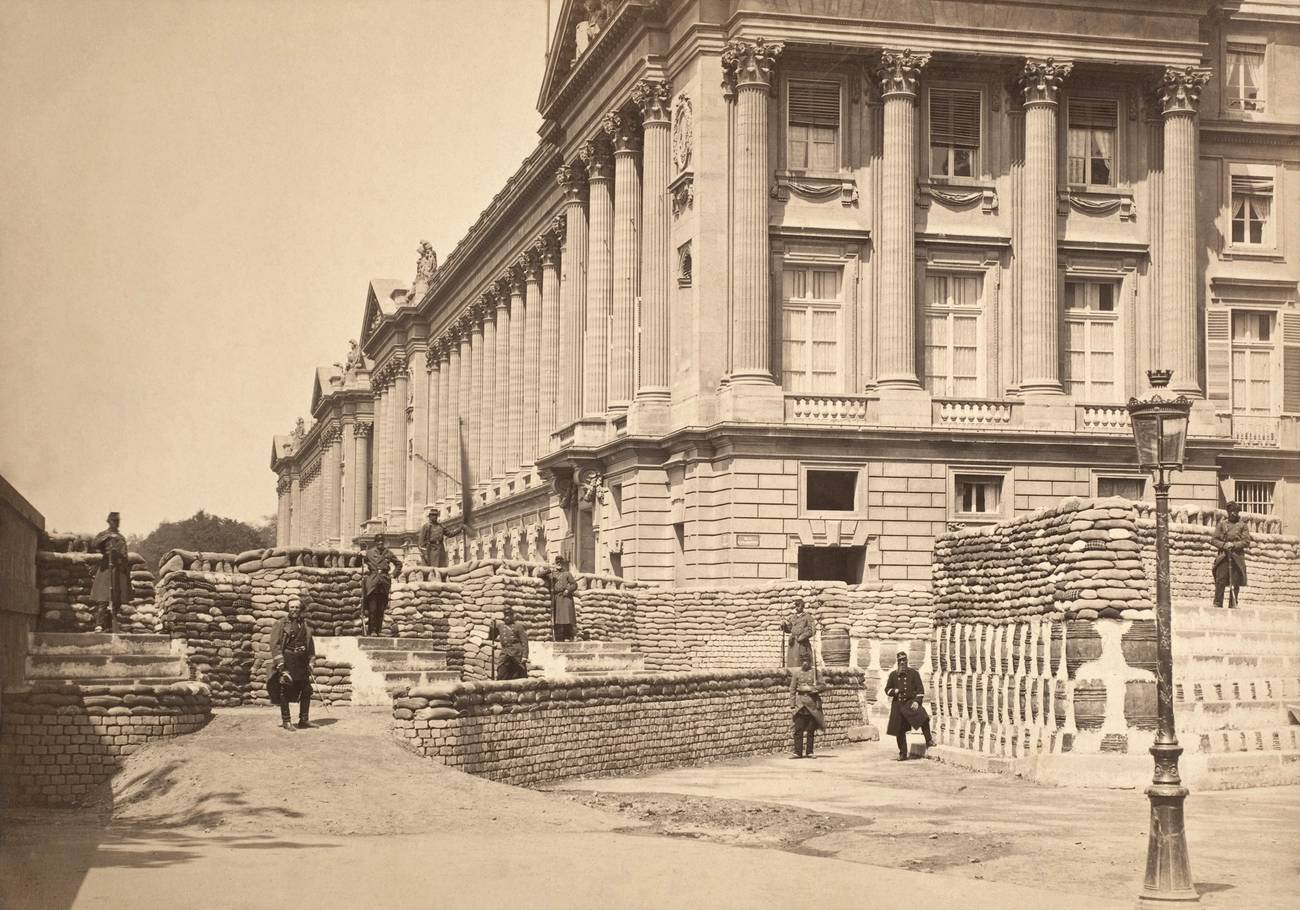

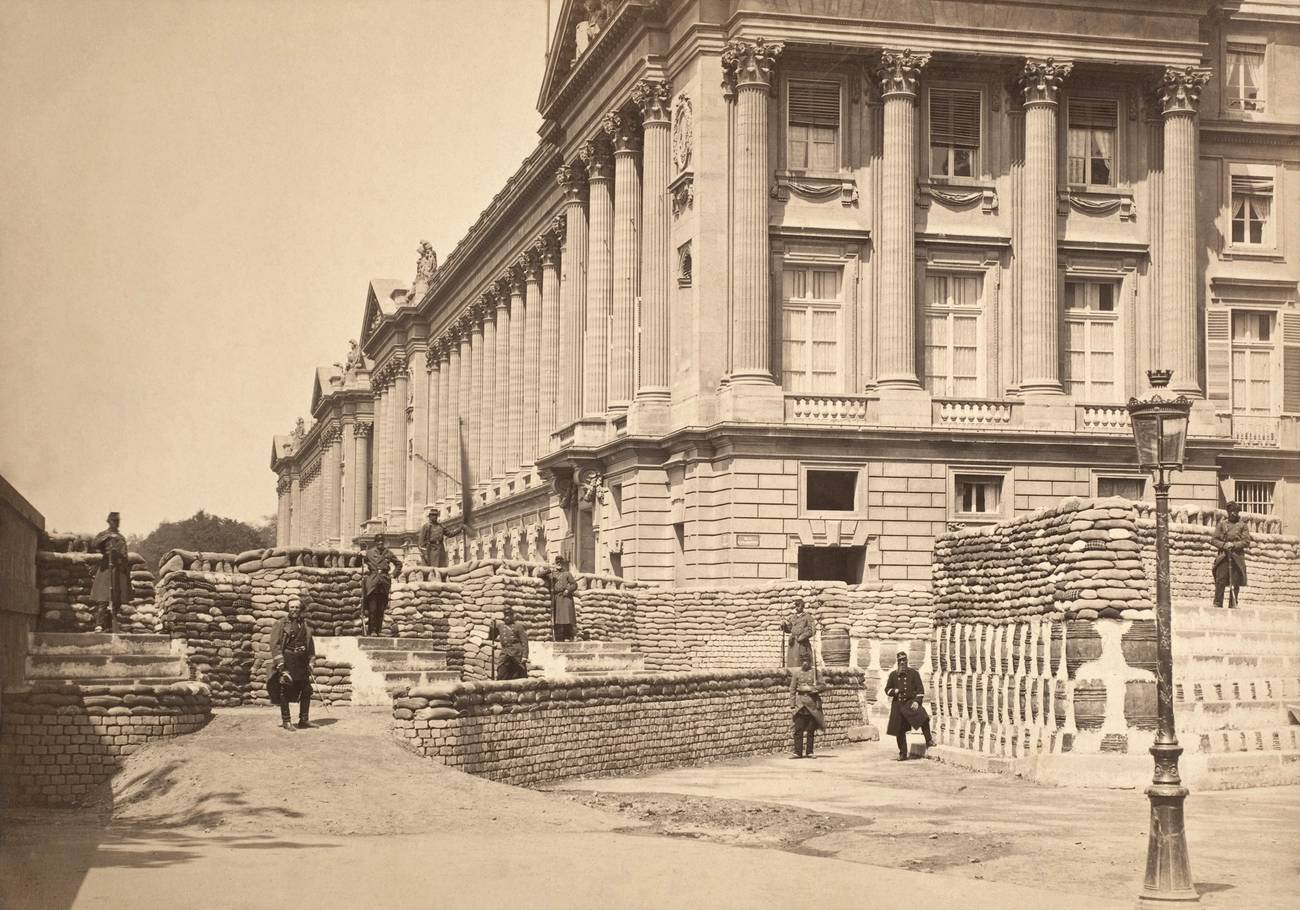

On March 18, 1871, troops of the new Third French Republic were ordered to seize the 250 cannons stationed around Paris. France had just been defeated by the Prussians in a war that their now-former emperor, Napoleon III, had provoked. Paris had suffered a horrific siege lasting from September 1870 to January 1871, during which its residents had been reduced to eating, among other things, salami made from rats. When the siege was finally lifted, Parisians were forced to submit to the indignity of Prussian troops marching through the city and to pay an enormous indemnity to the victors. So when word spread of the plan to seize the cannons in the working-class quarter of Montmartre, cannons paid for by the workers themselves, the residents in the heights of the city rebelled. By the late afternoon, the crowd had killed two generals leading the troops to remove the artillery, and within hours the people had seized the Hotel de Ville and placed the city under the rule of the Central Committee of the National Guard. Only they, and not the regularly constituted government, which had fled to Versailles behind its leader, Adolphe Thiers, could properly defend the city and the republic.

The spark that set off the revolution established it as something sui generis among working-class uprisings. As Antoine Brunel, a member of the National Guard and the Commune’s elected council, wrote years later, “The insurrection of 1871 is still misunderstood. It was first provoked by a patriotic sentiment and by the determination to prevent the monarchical form of government from taking possession of the country.” Only in France could a revolutionary seizure of power be set off by love for the patrie, the fatherland defended by the revolutionary army of 1793. It is commonly said that generals refight the last wars. The Paris Commune, for its part, refought the greatest of France’s revolutions, the one that began with the taking of the Bastille on July 14, 1789.

On March 26, elections were held for the council of the newly declared Paris Commune, the world’s first working-class government. The existing state was abolished, and a totally new social and democratic order put in its place. The enemy was no longer the troops of Bismarck, but the forces of the bourgeois republic. The true republic, spelled with an uppercase “R,” was inspired by the one founded by the heroes of the French Revolution.

The Commune lasted just 72 days, its final defenders slaughtered on May 28 as they fought among the graves at Père Lachaise Cemetery. But the very brevity of the Commune’s existence added to its luster; it became history’s great might-have-been.

After its demise, the Commune became all things to all people on the left; for some, the first socialist state, for others, anarchism in action. For Friedrich Engels, as he wrote in his postscript to Marx’s The Civil War in France, it was the “dictatorship of the proletariat” that he and Marx and the First International had long called for. It was, in reality, not just the first revolution of its kind, but in many ways the last, above all a product and prisoner of France’s particular conditions and history. The measures implemented by the Commune, a form of government that, like so much else about its foundations, harked back to the French Revolution, would be echoed through the decades, inspiring movements around the world and playing an essential role in the rise of the left. But if Engels is right and the Paris Commune was the embodiment of the dictatorship of the proletariat, many of those who later invoked their ideas ultimately betrayed them.

Elections for the Commune council took place a week after the attempted seizure of the cannons. They were carried out in every arrondissement of Paris, though those elected to the Commune’s council from the bourgeois neighborhoods did not take their seats. The resulting body had three factions, confirming the hold still maintained by Robespierre, with the main victors in the election being the neo-Jacobins.

This fidelity to the past held as well for the second-largest group of Communards elected, the followers of the eternal conspirator Auguste Blanqui. As Gaston DaCosta, a leading figure among the Blanquists, wrote in his memoir of the period, “At the time the Blanquists were the only thing that they could be: Jacobin revolutionaries rising up to defend the threatened republic.”

The Blanquists, with their conspiratorial groups, putschist tendencies, and fealty to a unique leader, were precursors to the Bolsheviks of Lenin. But in March 1871, they were Bolsheviks without a Lenin, for their leader had been imprisoned for his part in a failed uprising in January of that year. When the Commune took hostages in an attempt to halt the massacres of Communards by the troops of Versailles (known as the Versaillais, or ruraux), they offered to trade all of their hostages for Blanqui. Adolphe Thiers refused the exchange.

The third group within the Commune was the members of Karl Marx’s First International. Given the later history of the movement, the role and positions of the followers of the International were, on the surface, unexpected.

DaCosta described these men as “nothing but dreamers,” lacking a “defined socialist program,” which certainly seems an odd characterization for those aligned with Marx’s International. But few of the members of the International in Paris were Marxists, and Engels described them as followers of Proudhon. Some were, but this characterization is inaccurate. The French section included the most unflinching republicans, those most dedicated to a republic that was free and just, to what they called “La sociale.” “Communists,” i.e., Marxists, were rare among the French members of the International, and anarchism had no role in the Commune; in fact, the movement did not yet exist in France. The followers of the International, who came to be called the Minority, were the only members of the Commune who admired the French Revolution but weren’t in thrall to it.

Among Communards, it was the members of the International who were the strongest defenders of the broadest possible democracy within the walls of Paris. Jules Vallès, their greatest writer, even defended the right of the conservative newspaper Le Figaro to publish while the city was being attacked by the forces of Versailles. But they went further still. In the final weeks of the Commune, the two larger factions, taking their Jacobin and sans-culotte roots to their ultimate extremes, proposed the establishment of a dictatorial Committee of Public Safety and the execution of the Communard-held hostages in response to the killing of Commune fighters by the Versaillais. The Minority then announced that it would no longer attend the sittings of the Commune’s council and that its members would retire to their arrondissements to participate in the fight alongside their constituents. Though they relented and took their places on the council, it is nonetheless important to remember that it was the members of the International who were, if not followers of Marx and Engels, certainly the closest to them and their movement, who, amid a bloody revolution, refused dictatorial measures.

Along with the establishment of a state of, by, and for the working class, the Commune’s claim to greatness is the remarkable range of measures it passed. Rent payments were deferred, as were debt obligations for a period of three years, with no accrual of interest; goods held in the government pawnshop were released to their owners; the separation of church and state was declared, with the government no longer funding church operations and all religious emblems removed from classrooms; the standing army was abolished, replaced by the National Guard, with its officers elected by its members; the guillotine was publicly burned; all elected members of the Commune’s council were made revocable, with their wages limited to those of a worker; factories closed down by their owners during the siege and Commune were to be turned into cooperative enterprises under worker control; and night work for bakers was banned. The Vendome Column, the symbol of Napoleonic military glory, was torn down, its demolition organized by Gustave Courbet.

The Commune also opened the way for the emancipation of women, allowing them a greater role in politics than they had previously enjoyed. The name of Louise Michel, who headed a vigilance committee and organized an ambulance service, is the best known of the female Communards, but there were others of note. The most important organization was the Union of Women for the Defense of Paris and the Care of the Wounded, co-founded by the Russian emigré Elisabeth Dmitrieff, who also fought at the barricades in the final days of the Commune and later fled to Switzerland. Women weren’t granted the vote or the right to sit on the Commune, but they played a key role at the barricades and were involved in the fight from its first day. The Communards famously set fire to many of Paris’ most famous and important buildings, the arson attributed to roving bands of revolutionary women known as Les Petroleuses. Some historians have cast doubt on the existence of these vandals, but legend or fact, they elevated the women of the Paris Commune to a fearsome role in the uprising.

Many of the measures passed by the Commune were dead on arrival, the expression of pious wishes unrealizable given the circumstances and the time allowed them. Jean Grave, one of the major voices of French anarchism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, would say a quarter of a century later that most of the measures passed weren’t implemented “because those they were aimed at realized that the Commune legislated much but acted little.” They still mattered; in his classic novel about the final days of the Second Empire and the Commune, L’Insurgé, Jules Vallès quotes a Communard as saying that it was important to show “what we wanted (even) if we can’t do what we want.”

These measures were not the fruit of spontaneous outbursts of the people, but of parliamentary action. The Commune was not an anarchist body or a general assembly in the spirit of Occupy; it was not the people who were engaged in direct democracy. The election of officers of the National Guard, which might be considered a sign of its anarchist foundations, predated the Commune. When the newly elected council of the Commune swept away the old state, it replaced it with a number of different departments, called commissions, all headed by a délégué. Despite its Robespierrist leanings, the Commune did not have a permanent head, its sessions run instead by a revolving series of presiding officers. Measures were proposed and discussed and parliamentary order was scrupulously followed. Like any French government, it had a Journal Officiel, which reported the debates in the Commune. Faithful to the traditions of French democracy, elected officials even wore a sash of office, replacing the blue, white, and red sash of the republic with a simple red one.

There is something impressive, moving, and quixotic about an assembly of workingmen and old-time opponents of the expired empire establishing a legislative body that discussed policy matters freely, refusing, almost till the end, to imitate the enemy’s brutality.

The Commune was the first step in the rise of the left, but despite all hopes and expectations, that rise was the beginning of its fall.

The Commune was defeated, and during the last week of its existence, the Bloody Week, 20,000 workers were killed by the forces of Versailles. Thousands more were driven into exile, imprisoned, or deported to penal colonies. The French working-class movement was decapitated and its momentum delayed for years until a general amnesty was granted in 1879.

A victory of the Commune was likely never possible. Abortive attempts at the establishment of Communes elsewhere in France at the time of the Paris uprising were quickly extinguished. In essence, Paris had seceded from France. If the Communards of Paris dreamed of a federation of Communes (from which they derived their name of fédérés), they had no one to federate with. Blanqui, the greatest figure on the left, might have been a leader around whom all could unite, but his history of failure in his many revolutionary putsch attempts hardly leads one to believe that he would have turned things around and led the forces of the Commune to victory. In any case, he was, as mentioned above, in prison during the Commune. Victor Jaclard, an officer in the National Guard, later wrote that Blanqui might have had the necessary “decisiveness,” but if things had been different and Blanqui was available to lead the fight, “he would have been, like so many others, an impotent force paralyzed by circumstances. Locked within Paris, the Commune was buried before it was dead.”

Under any circumstances, even an army as highly motivated as the Commune’s National Guard would have had an almost impossible task in defeating the army of Versailles. The National Guard was essentially the people in arms, which fulfills a romantic notion of a revolutionary army, but in reality, the people of one city taking on the forces of an entire country—in this case, their own country—is a monumental and likely hopeless undertaking. The Commune’s strategy wavered between sending its armed forces out to meet the army of the Republic outside the city’s walls or waiting within the walls and making it clear they were the victims. Failed sorties early on forced them to remain on the defensive, and their generals rotated through command at a dizzying pace, replaced when defeated in battle and, more often than not, accused of treason.

Enemies of the Commune inside Paris are said to have allowed the first troops of Versailles to enter the city, and the defense was poorly organized, with Communard fighters concentrating mainly, and sometimes solely, on the battles and barricades in their individual arrondissements or streets. No general defense plan was developed, and the result was a revolutionary sauve qui peut.

It’s often forgotten that even had the Communards defeated the Versaillais militarily, the Prussians were still on French soil. A breakthrough of Versaillais lines or a defeat of Thiers’ army would have led to the return of the Prussians and the certain crushing of the Commune. Jean-Baptiste Clément, a member of the Commune and the International and the author of one of the most famous French songs, “Le Temps des cerises,” later said that “Paris could have won out over Versailles, but to believe that would have implied the triumph of the social revolution would be naïve, for the Prussians weren’t far away and the provinces were all around us”.

In 1897 the literary magazine La Revue blanche, which included among its contributors many of France’s greatest minds, published a symposium on the Commune featuring contributors who were participants in the movement.

Some veterans now viewed it with a jaundiced eye. Jean-Louis Pindy, who became an anarchist and lived in Switzerland after the Commune’s fall, and who had ordered the setting aflame of the Hotel de Ville, felt the Commune hadn’t been harsh enough in its measures: “I think we acted like children who try to imitate grownups whose names and reputations subjugate them, and not like men with force … should have done in the face of the eternal enemy.”

Simon Dereure, a cobbler and member of the Minority faction of the International, felt that the Commune “concerned itself far too much with details it would have been preferable to see to only after the military victory.” Jean Grave, concurred with Dereure, saying that the Commune “was too parliamentary, financial, military, and administrative, and not revolutionary enough.” As a result, he mocked the idea that the Communards were revolutionaries.“ That’s … what they thought they were, but only in words and parades. So little were they truly revolutionaries that even invested with the suffrage of the Parisians they continued to consider themselves intruders in the halls of power.”

Alphonse Humbert, the editor of one of the most extreme newspapers of the Commune, was frankly dismissive of the whole affair. “I consider the Commune a heroic act; this and nothing else, for I don’t think it marked a date in the history of socialism.”

Many of the veterans were still angry that, despite the fact that the Commune needed funds to pay the National Guardsmen and those building barricades, they showed far too much respect for legality by not touching the money held in the Bank of France. Jean Allemane, later the leader of a faction of French socialism, complained that “instead of chattering it should have struck the bourgeoisie at its most sensitive point: the safe!”

Not everyone took so gloomy a view of the uprising. For Louise Michel, the Commune set a shining example for the struggles ahead: “Every revolution will now be social and not political; this was the final breath, the ultimate aspiration of the Commune in the ferocious grandeur of its marriage with death.” The Communard Edouard Vaillant, who would later be a founding member of the Socialist Party, evoked the Commune’s international reach: “If socialism wasn’t born of the Commune, it is from the Commune that dates that segment of the international revolution that no longer wants to give battle in a city only to be surrounded and crushed, but which instead wants, at the head of the proletarians of each and every country, to attack national and international reaction and put an end to the capitalist regime.”

The Commune’s defeat had ennobled it. The relative handful of hostages executed in its waning days, including the archbishop of Paris, paled before the mass killings carried out by the victors and the worthiness of its goals. The Communards had “stormed the heavens” and failed. Its reputation was relatively unstained. The same cannot be said of many of those it inspired.

Vaillant and Michel were right: The Commune would serve as an inspiration for almost every movement in every corner of the globe that aimed to replace capitalism with a more just order. From socialists to communists to anarchists to freethinkers and even Freemasons, all found inspiration in that brief moment of French history. Those days in 1871 fed into a vision of history in which a final violent cataclysm would bring down the old order and replace it with a world cleansed of the rot of the past, what the French called the grand soir. And yet, almost all of the heirs of the Commune failed, and the few that emerged victoriously betrayed what the Commune stood for in achieving that victory. The Commune was the first step in the rise of the left, but despite all hopes and expectations, that rise was the beginning of its fall.

The failures were many. The Spartacists of Germany in 1919, the revolution in Hungary in that same year, and the Shanghai Commune of 1927, were inspired at least in part by the Paris Commune; all ended in bloodbaths. Revolutionary Barcelona in 1936 and France in May and June 1968, both sought a different, more human way to organize society that recalled the hopes of 1871. Their barricades, banners, and slogans were imbued with the spirit of Commune, and yet they, too, succumbed.

The Commune’s example was most loudly proclaimed in Soviet Russia and People’s China. Lenin is reputed to have danced for joy in the snow the day the Bolshevik state outlived the Commune. But the same Lenin would write in The State and Revolution that, “It is still necessary to suppress the bourgeoisie and crush their resistance. This was particularly necessary for the Commune; one of the reasons for its defeat was that it did not do this with sufficient determination.” The “determination” he had in mind was embodied in a state that was the negation of the Commune until the latter was in its death throes, silencing all opposition and developing a police apparatus that did not hesitate to jail and kill its enemies.

The Russian Revolution survived, not for 72 days, but for 75 years, the span of a single lifetime. In the process of doing so, in choosing to survive by any means necessary, by resorting to dictatorship, by killing millions of its own people, it permanently sullied socialism. Its victory, which seemed to promise a new road for humanity, instead closed the road off.

China fared no better. It not only invoked the example of the Commune in 1927 with the Shanghai Commune, but 17 years after achieving power, in 1966, Mao conjured the Commune’s shade in the form of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. The Cultural Revolution, which Mao fomented in an effort to emulate the Commune’s destruction of the existing bureaucracy, resulted in millions of deaths, the ruin of the nation’s economy, famine, and even cannibalism. Its excesses caused a revulsion against socialism within China that led directly to the savage capitalism that has replaced the Maoist state.

Mitchell Abidor is a writer and translator who has published over a dozen books on French radical history.