The Best Booze-Busters in Brooklyn

The government’s most successful Prohibition agents were two overweight Jewish guys from New York, who arrested 4,932 people and regularly wore fake mustaches

In 1917, the United States government passed the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, making it a crime to manufacture, sell, or transport alcoholic beverages. The act was ratified by the necessary three-quarters of the states in 1919, and the Volstead Act enforcing the 18th Amendment went into effect in 1920, officially making the federal government responsible for keeping the nation dry. To do so, the government created the Prohibition Bureau.

The 18th Amendment was the culmination of a decadeslong campaign by small-town Protestant Americans who believed that alcohol lay at the core of most big-city social ills, such as crime, vice, and broken families. They felt that a sober America was a greater and more successful America. This view was joyfully expressed by Billy Sunday, a former baseball player turned evangelist. “Goodbye, John Barleycorn,” he exulted. “You were God’s worst enemy. You were hell’s best friend. The reign of tears is over.” How wrong he was.

The ban on alcohol went into effect at midnight, Jan. 16, 1920, and from that moment on it seemed that every American over the age of 12 had to have a drink. Two hundred thousand unlicensed saloons selling illegal, or “bootleg,” whiskey sprang up across the United States. These bars and restaurants were euphemistically called “speakeasies” and “blind pigs.”

The criminal underworld also stepped in to quench the great American thirst by providing Americans with booze. Prohibition provided an opportunity for organized crime, especially in its violent forms, to blossom into an important force in American society. As Al Capone would put it, Jews, gentiles, the government, and a lot of “respectable” Americans as well, would soon learn, “You can’t cure a thirst by law.”

In 1929, the police commissioner of New York City estimated that there were 32,000 speakeasies in the metropolis, double the number of saloons before Prohibition. The city of Chicago contained over 10,000 illegal speakeasies by 1925. In Detroit, there were over 7,000 speakeasies in the city in 1920. By 1928, the figure had risen to 25,000. The Detroit News reported that in some parts of the city speakeasy. One of the newspaper’s investigative journalists found 150 separate speakeasies on a single block.

In New Orleans, rum-running became a way of life for many people after the official codification of Prohibition. Hundreds of New Orleans’ citizens brewed their own alcoholic drinks in their bathtubs at home. As early as 1920, city officials estimated that more than 10,000 residents of New Orleans had already broken the law. Newspaper reporters openly chilled their beer in the city morgue because the morgue was kept extremely cold to preserve the bodies.

To combat this drinking binge, the government made 17,972 appointments to the federal Prohibition Bureau in the first 11 years of its existence. Sixteen thousand of these appointees were dismissed for cause. The grounds for these dismissals included bribery, extortion, theft, violation of the National Prohibition Act, falsification of records, conspiracy, forgery, perjury, and more. The rapid turnover of agents in the Prohibition service and the notoriety of some of them gave the service a bad name. One disgruntled agent called the bureau “a training school for bootleggers,” because so many agents who left the service promptly sold their expert knowledge.

Article 7 of the Volstead Act exempted the production and sale of wine for sacramental purposes. This led to a huge increase in false rabbis who served as conduits for the sale of “sacramental wine.” One Prohibition agent mused that there was no discipline and no control in the Jewish faith. “Anybody can become a rabbi, and the bootlegger has taken advantage of it.” In New York City alone almost 3 million gallons of sacramental wine, more than a gallon for each Jewish man, woman, and child, were consumed during the fiscal year ending June 1924. Many of these so-called “wine rabbis” established fictional congregations in the wine localities of California in order to peddle their wares.

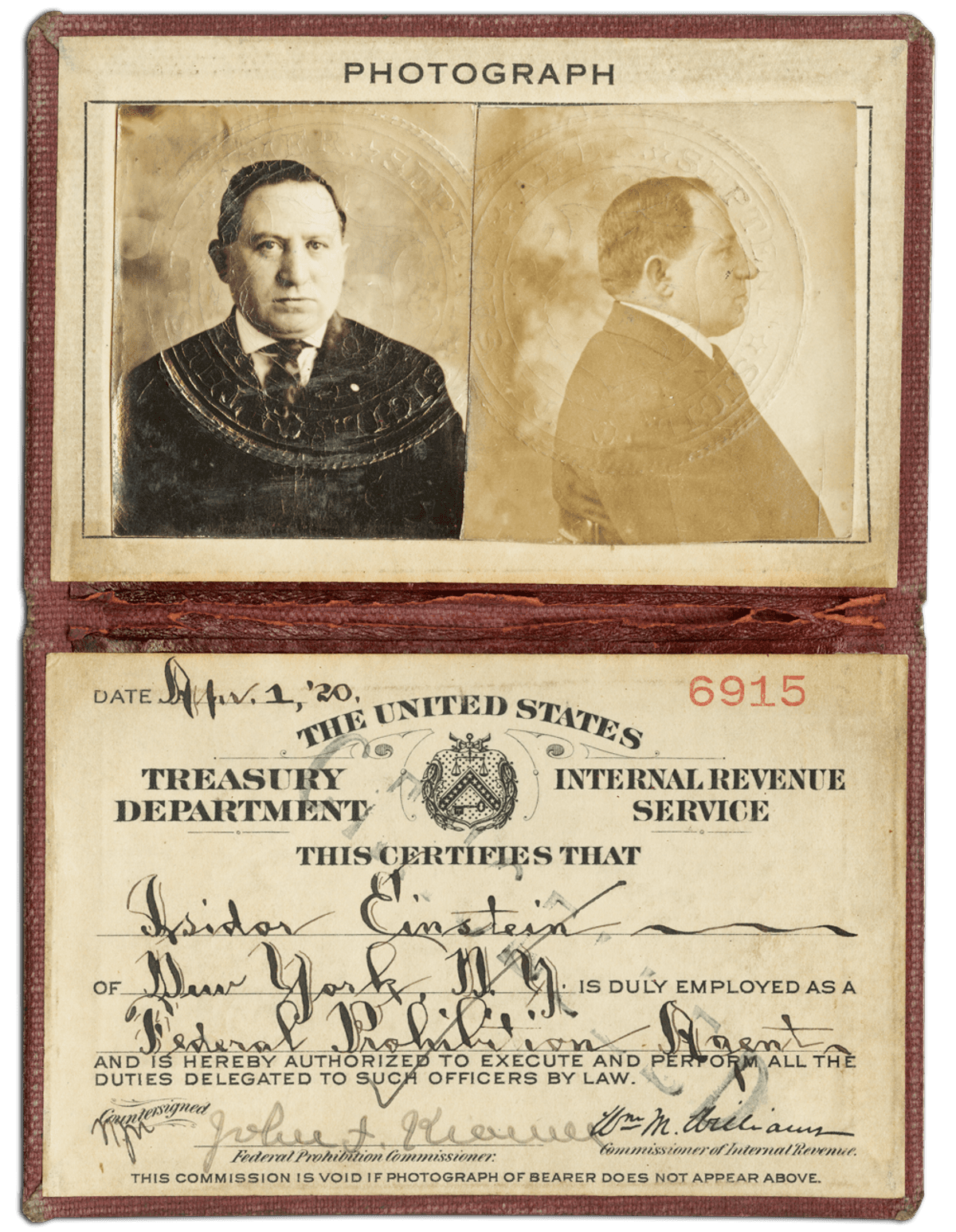

Despite its many failures, the Prohibition Bureau employed some outstanding and incorruptible agents. Two of them were Jewish friends from Brooklyn: Isidor “Izzy” Einstein and Moe Smith. They became known nationally for successfully blowing up and destroying illegal speakeasies and for using all manner of disguises in their work, with Izzy becoming the more famous of the two. He was so successful at nabbing lawbreakers that he was considered to be the federal government’s No. 1 Prohibition agent.

Both men were short and fat, each weighing over 200 pounds. They looked nothing like government agents—and certainly nothing like the image later projected in Hollywood movies. But their unassuming appearances proved to be the secret of their success. They became so successful that some speakeasies posted pictures of them as a warning to customers. Hundreds of hilarious newspaper stories were written about the pair and the public enjoyed reading about them.

Izzy was born in Austria or Hungary in 1880, but grew up in New York’s Lower East Side. He was likely educated in a yeshiva and spoke fluent Yiddish, Italian, Hungarian, German, Bohemian, and Polish. He had been a dry goods salesman and post office mail sorter before becoming a Prohibition agent. This upset his Orthodox father, who hoped Izzy would become a rabbi.

When Izzy applied to the Prohibition unit’s Manhattan office in 1920, the office initially rejected him as an unconvincing law enforcer. He would be the first to admit that he didn’t look like a detective. Prohibition agents were supposed to be athletically built with a menacing look. Izzy was neither. Time magazine once described him as a “fat, little Austrian Jew.” (Time had a predilection for always identifying Jewish criminals as “Jews.”)

But Izzy made the case that the bureau could use his tubby stature, waddling stride, and ethnic Jewish-looking features to his advantage. He could be successful as an agent, he said, because no one could imagine that someone looking and walking like him could possibly be a detective. He promised the bureau that he could get results that the regular plainclothes men couldn’t. He might not be able to outrun bootleggers and saloonkeepers, but he believed that he could outwit them by looking like one of their customers—and he was right. Despite his crusades against them, even the bootleggers loved hearing about his exploits and regarded him with humorous affection. One Georgia moonshiner even named his dog after him.

He and his partner, Moe, gained national fame because of their productivity. From 1920 to 1925 the pair confiscated 5 million bottles of liquor and arrested 4,392 persons. Ninety-five percent of those arrested were convicted, setting an agency record.

Reporters were particularly drawn to “Izzy and Moe” because of their investigatory methods, which were often distinctive and comical. Izzy used his knowledge of languages to infiltrate immigrant communities in cities all over the country, which most native-born bureau agents could not do. The variety of disguises they used when making their raids seemed endless. They wore false whiskers and noses. They put on blackface. They dressed as society dandies, pickle peddlers, streetcar conductors, gravediggers, fishermen, icemen, opera singers, college athletes, and as the state of Kentucky delegates to the Democratic National Convention of 1924 held in New York City, where they found only soda being served. Once they donned football uniforms to bust a speakeasy serving thirsty athletes playing in a Brooklyn park. A few times Einstein went into a bar and identified himself as a Prohibition agent. The bouncer, thinking he was joking, laughed and let him in. One time he took bets from customers in a saloon that he was the agent whose picture was on the wall. When the customers paid up, he arrested them.

Izzy busted one particular Coney Island speakeasy in midwinter by swimming with a polar bear club, and almost froze to death. A concerned Moe rushed the shivering Izzy into the clubhouse. “Quick,” he cried, “some liquor for my friend before he freezes to death.” When the bartender quickly provided the liquor, Moe arrested him.

On one occasion, he was served liquor at a midtown club by convincing the bartender that he was a rabbi. On another occasion, he convinced a saloonkeeper who recognized him that he was not Izzy Einstein by pretending to eat a ham sandwich, something the real Izzy, who kept kosher, would never do. Izzy reveled in the role of a Jewish trickster and his stereotypical Jewish look. He once told a reporter in Mobile, Alabama, that he fooled saloonkeepers so well because he was regularly taken for granted as a traveling salesman.

Once, Izzy happened to meet the famous Albert Einstein. Not knowing him, Izzy asked Einstein what he did for a living. “I discover stars in the sky,” replied the scientist. I am a discoverer too,” said Izzy. “Only I discover in the basements.”

The team worked primarily in the New York area, but their reputation led to local bureaus in other cities to ask for their help in busting the Prohibition problems in their towns. Thus it was that Izzy was invited to come to Detroit. Izzy’s method proved successful there. Sporting a mustache and dressed as an autoworker, Izzy walked into a Woodward Avenue speakeasy and asked for a drink. Generally, most illegal drinking saloons refused to serve a prospective customer if he was not known to the bartender or other customers. As an added protection, many speakeasies kept photographs of local and federal enforcement officers in an album behind the bar.

The Detroit bartender refused to serve Izzy because, he said, pointing to a black-framed photograph of Einstein, “Izzy Epstein’s in town.”

You mean Einstein, don’t you?” asked Izzy.

“Epstein,” insisted the bartender.

“I bet you a drink it’s Einstein,” said Izzy.

“You’re on,” said the bartender.

The bartender poured Izzy a shot of whiskey, which Izzy emptied into a secret funnel sewed to his breast pocket and connected by a long rubber tube to a concealed flask he used to gather evidence.

“There’s sad news here,” Izzy announced in a mournful voice. “You’re under arrest.”

Izzy and Moe further used the press to build support by scheduling their raids to suit the convenience and the newspaper photographers. They quickly learned that there was more room in the newspapers on Monday mornings than on any other day of the week. One Sunday, accompanied by a swarm of eager reporters, they established a record by making 71 raids in less than 12 hours.

Izzy and Moe retired in 1925—or more accurately, they were relieved of their duties because the heads of the Prohibition Bureau were jealous of all the good publicity they got. They made the front pages of the newspapers more often than anyone except the president and the British Prince of Wales.

In their retirement, both men went into the insurance business and soon numbered among their clients many of those they had once arrested. In 1932, he wrote an autobiography titled Prohibition Agent No. 1, which he dedicated to all the people he’d arrested. Their adventures were also immortalized in a movie called Izzy & Moe.

Izzy died at age 57 on Feb. 17, 1938, several days after having a leg amputated. He was buried at Mount Zion Cemetery, in Queens, New York. Moe Smith lived until 1960, when he died from a stroke in Yonkers, New York.

After their deaths, each man was featured in an obituary in the national magazine Time, which noted their joint achievements during Prohibition as the “funniest and most effective team” of federal agents, who made almost 5,000 arrests and confiscated an estimated 5 million bottles of liquor.

Robert Rockaway is professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University, and the author of But He Was Good to His Mother: The Lives and Crimes of Jewish Gangsters.