The Glory of the Kings

Our ‘History Detective’ columnist provides a chronological dictionary of key people and terms that tells the story of Ethiopian Jews

Terminology: Here I use “Ethiopian” and “Abyssinian” almost interchangeably. However, the Classical (Greco-Roman) authors called by name “Ethiopians” those Black Africans who lived outside the Greco-Roman world and beyond its/their control. The country we now know as Ethiopia rose from the Aksum kingdom of the first Christian centuries and was later called Abyssinia, from Arabic Ḥabash, itself from South-Arabian ḤBŚT in Yemen.

In the last centuries, the word “Abyssinia/Ḥabash” began to seem offensive to many Abyssinians/Ethiopians, and in the wake of the invasion of Fascist Italia in 1935, some local supporters of Mussolini were among those who promoted the change of the name of the country from Abyssinia to Ethiopia (though the Fascist “Ethiopian Empire” included Eritrea and Italian Somali). In recent years, especially in the U.S. diaspora, the name Abyssinia is in vogue again. Many Ethiopians, Eritreans, Djibouties, and Somalians are not part of the U.S. dichotomy of “Blacks and whites” and insist they are racially Ḥabesha/Habeshi, etc.

The term “Ethiopian” was adopted, mainly in the past, by many Afro-American and Afro-Caribbean intellectuals, among others, as a continuation of the Classical usage for all Black Africans. This usage had a role in the acceptance of the Abyssianian Crown Prince Ras Tafari as a Pan-African messianic figure. Nowadays, some claim that the Ethiopian state has no right to usurp the term for itself.

Kebra Nagast (The Glory of the Kings), Solomon, the Queen of Sheba, and the Abyssinian/Ethiopian self-image

The book called “the Ethiopian Second Bible,” Kebra Nagast, the Glory of the Kings, tells how the Queen of Sheba seduced King Solomon and gave birth to their son, Menelik I, the founder of the Solomonic Dynasty of Ethiopia. When he grew up, Menelik visited his father and returned to his country with the sons of the best men of Jerusalem and Judea. These were the ancestors of the present-day Ethiopian Christians.

As a real son of her trickster mother, he trickstered the Ark of the Covenant from Jerusalem. This is kept in the Church of the Virgin of Sion at Aksum. Nobody has seen it, no one, not even the man in charge who may not leave the precincts. That’s what Ethiopians and some Westerners believe. All Ethiopian churches contain a replica of the original Ark.

As physical descendants of Judean aristocracy of Solomon’s age, Ethiopian Christians are the real Israel of flesh. As Christians, they are the real Israel in spiritu (just as other Christians are), being thus Israel twice. And they are thrice Israel, as the only correct Christians after Chalcedon (well, together with Copts, Armenians, and Syriac Jacobites).

Aksum and Yemen/Ḥimyar

Ethiopian civilization was an offshoot of that of Southern Arabia, Arabia Felix, roughly Yemen. Ethiopia shared with Southern Arabia language, script, and many common features. Ethiopia became a Christian nation in the 330s, alongside the Roman Empire, Armenia, and Georgia.

In Southern Arabia, Judaism became a widespread religion in the fourth and fifth centuries (alongside at least two versions of Christianity), and in the first quarter of the sixth century the two countries, Christian Aksum and (by then jihādi) Jewish Ḥimyar, clashed in a Byzantino-Sasanian proxy war, something like a Sovieto-Sino-American Vietnam War. Jews lost in Yemen, but so did the Aksumites, too: After the 525 Jewish-Ḥimyarite defeat, both countries began to disintegrate, and then what we know as Early Islam arose on the ruins, borrowing from the heritage of both countries, but especially of that of Ḥimyar (with the original Judeo-Ḥimyarite idea of gehād, the Epiphany of the Jewish God of Armies here and now, reinterpreted).

The nascent Islam and Aksum Najāshi

Al-Najāshi (Negus) was the king of Aksum who sheltered the first Muslims of Mecca from persecution in their city during the First Hijra of 613-615/6 CE (9-7 BH), after the Sassanian Persians, supported by Jews, captured Jerusalem in 614 from the Byzantines. Eleven men and four women in the first group to cross the sea to Aksum included Muḥammad’s daughter Ruqayyah and her husband ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān, to later become the third Islamic Khalifah. The second group was much bigger, 83 men and 18 women. When asked what they believe in, the Muslim representative quoted the opening verses of the surat Maryam that retell the prayer of Zachariah in the Temple on account of his desire to have a son (the future John the Baptist).

In the Islamic view, the al-Najāshi (Negus) who sheltered the first muhājirin accepted Islam and the Islamic prophet prayed for his soul when the news of his death arrived. The Jihād against Abyssinia was forbidden and there are several Ḥadiths about the matter.

Jews of Yemen, Jews of Aksum/Abyssinia/Ethiopia

Jews survived in Yemen for another millennium and a half; Christianity was soon wiped out.

We know zero about Jews in Aksum prior to 525; we know almost zero about them much later, too, but one can imagine Jewish prisoners of war brought from Yemen to Aksum; however, Ethiopian legends subscribe to the idea that the Jews of Ethiopia descend from the refugees of Titus (although the word ayhud was virtually unknown to Ethiopia’s Jews).

Ethiopian Christianity and Judaism share many features, like circumcision, laws of kashrut, Christians keeping both the “Jewish Sabbath” and the “Christian Sabbath.” Around 970, Aksum was destroyed, possibly by a non-Christian (Jewish? pagan?) Cushite queen, whose name was interpreted as “Judith.” The problem is, it makes sense in English only.

Eldad the Danite

Earlier, in the second part of the ninth century, one Eldad ha-Dani pretended, in Babylonia and in Qairouan, to be a citizen of a Free Hebrew State of the tribes of Dan, Asher, Gad, and Naphtali. This state was placed by scholars in Arabia or Ethiopia; the problems are that there was no place to map it in historical Arabia, and, given the fact that Eldad pretended to speak the purest Hebrew only, and no Hebrew was known in Ethiopia until the late 19th century, his country must be looked for somewhere else (if it was real). Eldad’s situation would look better had he lived just a century later: With no Aksum kingdom after 970, one could make a lot of happy speculations about a Jewish state on the plateau of Simien. But again, the Hebrew question persists: no Hebrew in Ethiopia prior to the arrival of missionaries and Jewish scholars from Europe in the second half of the 19th century.

The “Solomonic” Dynasty, New Historical Myths, and “Ethiopian Protestantism”

In 1270, the Zagwe (i.e., Cushite Agawa) Dynasty was overturned in Abyssinia by an Amharic prince from the South, Yekuno Amlāk (r. 1270-1285). It was only then that the Solomonic legend was established, the previous dynasty was declared to be unholy (and Cushite!) usurpers, icons and frescoes first appeared in Abyssinian churches, and Kebra Nagast was composed.

As a reaction to the new Iconodoulia, an itinerant preacher, Abba Estifanos established in the early 15th century a new schism in the Ethiopian Church which is seen in the late 20th century as a forerunner of Iconoclastic Protestantism. Like the later-day Calvinists, they believed in salvation by grace, veneration of God alone (no angels, no saints, no icons, no kowtow to the monarch); in addition, they rejected the claims of the Solomonic Dynasty to its connection with Solomon, rejected the replicas of the Ark of the Covenant kept in the inner debir of the churches, and, like the Protestants later in Europe, converted the Ethiopian sanctuary temples modeled on the Temple of Solomon into congregational houses. It is not impossible that some of the heavily persecuted partisans of Abba Estefanos joined some Jewish groups whose existence is mentioned in the 16th-century Ethiopian chronicles telling about their armed resistance to the Solomonic Dynasty.

Ottomans, Jihād, Crusade, a short Catholic Episode

In 1516-20, parts of Central and Eastern Turkey of today, Egypt, Syria and Hijaz were conquered by a European superpower—the Ottoman Empire. Till then, the Ottoman Empire was a post-Byzantine European-Balkan state with some possessions in Asia, disguised as an Islamic machine of rolling war. The ruler of the empire was a Roman caesar (qayser-i Rum) and a khan (called by the Franks sultan; the myth of the Ottoman ruler as an Islamic khalifah had yet 250 years to wait). It was only after the conquest of the Old Muslim (on par with “Old Christian/New Christian”) Middle East that the Ottoman Empire began to Islamize itself seriously.

The first Ottoman attempt to conquer Yemen occurred in 1538, and in 1529–1543, Christian Abyssinia was the arena of a Jihād by the Somali (or, Harari) Sultan Aḥmad “the left-handed.” Ethiopians were able, with crucial assistance of 400 Portuguese musketeers brought by Christopher da Gama, the son of navigator Vasco da Gama, to overcome Aḥmad “the left-handed.”

In 1554, the Ottoman eyālet of Ḥabesh (Abyssinia) was established in theory, and three years later, Özdemir Pasha was sent to implement the conquest. For his conquest of Northern Abyssinia/Eritrea he became known as Habeşistan fâtihi, the “conqueror of Habeshistan.” Özdemir Pasha passed away in Debarwa in Eritrea in 1559/60.

The everlasting effect of the Ottoman conquest of the Abyssinian coast was the appearance of bun in Istanbul; fond of rare Arabic words to be found hidden deep in Arabic dictionaries, Ottoman intellectuals called the new beverage qahwah (some intoxicating drink), and about a century later, coffee arrived in Italy and began its march across the world.

Isac Akrish and RaDBaZ

In 1552, RaDBaZ (David b. Solomon ibn Abi Zimra) concluded that the members of what we call Beta Israel are Jews. At some unspecified period of time, between 1548-1554, Isaac ‘Akrish (c. 1530–1577/8?) mentioned that the Ottoman governor of Egypt showed him the letter sent by the Ottoman governor of Ḥabesh, DWSDWMWR [*Özdemir Pasha] where Özdemir wrote that “if not for the military assistance of a Jewish prince who had assisted me with 12,000 cavalry men, I would find myself in a grave danger losing all my armies.” In the same text, ‘Akrish mentioned an Italian sopher in Egypt who went crazy searching for information about Abyssinian Jews (a recurrent pattern, it seems; cf. further on Oheb-Ger Luzatto), and quoted other bits of news in Egypt about Jews in Abyssinia. The problem is chronological: Özdemir Pasha did not reach his still-theoretical Abyssinian eyālet when ‘Akrish left Egypt to Candia in 1554.

Isaac ‘Akrish was a Jewish Saloniki-born collector of books and publisher of rare rabbinic works. In many ways, he was a precursor of Avraham Firkowicz (cf. further). He went to Egypt c. 1548 where he got engaged as the tutor of grandchildren of David b. Solomon ibn Abi Zimra (1479–1573), the RaDBaZ, who served as the head of Egyptian Jewry (in 1517/8, the office of nagid was liquidated by the new Ottoman rulers and a new office, that of Ḥākām-bašı, was established instead).

‘Akrish spent all his money on purchasing manuscripts, and devoted all his spare time to copying those in Ibn Zimra’s library. It seems that among these or those was the 12th-century copy of the reply of the last Khazar king, Joseph, to the letter of Ḥasday ibn Shaprut. ‘Akrish apparently prepared an abridged copy for himself; the original longer copy was left somewhere in Egypt and came into possession of Abraham Firkowicz in 1864-65.

Leaving Egypt for Candia in 1554, ‘Akrish got into trouble with the Venetian authorities there who sought to confiscate and burn Talmud copies. Succeeding in rescuing his books, ‘Akrish got to Constantinopolis, then went back in 1562 to Egypt. After a while he returned to Constantinopolis and found there such patrons as Don Joseph ha-Nasi and Esther Kiera. They assisted him in hiring professional scribes to copy manuscripts. In 1569 a fire destroyed most of his books. He lived then for four years in the old Romaniot community of Castoria in poverty.

Back in Constantinopolis between 1575 and 1578, he began to print some of his books, without title pages or specific titles.

The first collection published was that of polemical writings, Iggeret Ogeret, including Profiat Duran’s Al Tehi ka-Abotekha; Shem Tov ibn Falaquera; and Qunteres Ḥibbut ha-Keber by ‘Akrish himself.

The second collection, Qol Mebasser, contained items about the Ten Lost Tribes, ‘Akrish’s introduction (quoted above), the letter of Ḥasdai ibn Shaprut to the king of the Khazars and the king’s reply mentioned above, and Ma‘aseh Beit David bi-Ymei Malkhut Paras, the story of Bustanai.

The “Hebrew Khazar Correspondence,” as it is known, was published by ‘Akrish to “strengthen the people in order that they should believe firmly that the Jews have a kingdom and dominion.” ‘Akrish wrote in his introduction that “I heard from many men, those of great importance and those of little importance, who talk about the matter of the Tribes, i.e., that there are certain places where there are kings of Israel who exercise might and power and lack nothing except the Temple Worship and Prophecy; that in every place where they are, they sit, each man under his vine and under his fig tree, ‘quietness and assurance for ever’ (Isa 32:17). They have nations and kings from amongst the nations of the world who are conquered by them, and they make war against the nations when they revolt against them. There are some who say that their place of living near the river Sabbathion, some say across the river Sabbathion, for thus is written in many places, and some say that they are after the Kingdom of Yemen inlands, and some say–across the river Gozan, as R. Binyamin [de Tudela] mentioned in his Travels, and so it is written recording the kings whom Sennacherib had exiled. Some say they are under the Mountains of Darkness, as mentioned Ben Gorion in his book regarding Alexandros. There are some amongst them who say they are beyond the Kingdom of Ḥabash, near Priesti Gouan [Priester John]. All these things are difficult in my eyes, as well as in the eyes of many men of more importance than I am, and this for many reasons.”

Oheb-Ger Luzzato, d’Abbadie, Stern, Rosenthal

In 1845, Oheb-Ger (Philoxène) Luzzato (1829-1854), a student of Ge‘ez and son of Samuel David Luzzatto (1800-1865), sent questions to the Jews of Ethiopia by hand of the explorer of the sources of the Nile (and many things more), Antoine Thomson d’Abbadie d’Arrast (1810-1897), an Irish-Basque in French service. In 1848, d’Abbadie returned to Europe with answers written by the highest leader of Beta Israel, Abba Isaac. Abba Isaac wrote that Shabbath prevents Beta Israel from traveling by sea (sounds like a motif from the tribes beyond Sambation); that they are poor (cf. further); and that they have no rist (hereditary plots of land, from the same root as Hebrew yərushah, and cf. further). They ask to send somebody from Jerusalem or Europe to visit them in Ethiopia in order to learn more about the faith, and ask what is the opinion of non-Ethiopian Jews about the coming of Tewodros (a Messianic figure based on Theodoros I, whose nine-month long reign in 1413/4 was seen as a golden age; Tewodros II who ruled in 1855-1868, and on whom further, chose his throne name on the basis of these Messianic expectations).

In 1860, the Anglican missionary of Jewish-German extraction (a rather common phenomenon among Anglican missionaries in the 19th century), Henry Aaron Stern (1820-1885) arrived in Abyssinia. Tewodros II first greeted Stern and his fellow German Jew turned Anglican missionary, Rosenthal, but they were forbidden to convert Jews to any form of Western Christianity, but to the traditional local Christian faith only. Stern attacked harshly such institutions of Beta Israel that they shared with their Christian compatriots as monasticism (monks served as religious leaders of Jews and Judaizants in Ethiopia), sacrifices, and priesthood. Stern’s most ominous adversary turned out to be a Jewish monk, Abba Mehari.

Abba Mehari and Flad

In 1862, Abba Mehari led masses of thousands from Northern Ethiopia to Jerusalem. Probably his decision was indirectly provoked by Stern’s attacks on his leadership. The so-called “shamans contest” is a phenomenon well known in religious disputes everywhere.

When they reached a big river, it was the rainy season already. Abba Mehari was not successful in splitting the waters like Moses did, and thousands drowned. One of the results was distress and disillusion that led many to embrace Protestant missionaries. One of those was the Lutheran German, Johann Martin Flad (who happened to know Abba Mehari personally), whom Stern left in Ethiopia as his own deputy when he departed to Britain to see his book, Wanderings Among the Falashas in Abyssinia: Together with Descriptions of the Country and Its Various Inhabitants, London, 1862, to be published. Flad used to preach clad in black like a raven, and on account of his black clothes, those converted by him became known as “Raven’s horses,” paras muqra, to become corrupted later into Falash-Mura. This is a popular etymology, of course. The word Falasha has nothing to do, as many tend to think, neither with Philistines nor with poləšīm, “intruders” in Hebrew. In fact, this is from falāšā, “landless person,” or more precisely, “one who has no right to take part in ‘the Amhara national sport’ of putting claims of possession of this or that spot of land.”

Napier

Stern was back in Abyssinia in 1863. News about his book containing derogatory statements about the mother of Emperor Tewodros II reached the capital; Stern was thrown in jail and flagellated. In prison, he soon met Rosenthal, Hormoz Rassam (1826-1910), the man who had found the Epic of Gilgamesh and now an envoy of Queen Victoria to Tewodros II, and the British consul, Charles Duncan Cameron, all of them taken hostages. In 1867, Tewodros made friendly noises toward the British in Egypt, desiring assistance against the inroads of Khedivian Egypt in Sudan and Abyssinia. Cameron wrote in his letter to the Foreign Office from his prison: “no release until civil answer to King’s letter arrives.” Meanwhile, the missionaries and diplomats were put in irons and spent about two years in prison (with Cameron and Rassam shortly released and then rearrested) until British and Indian troops under Robert Napier arrived, burned down Amba Magdala, freed the hostages, and looted books and antiquities and curiosities. The British lost just two men.

The emperor killed himself with a pistol as the final assault at Magdala began; Robert Napier was made the First Baron of Magdala; Empress Tiruwork Wube and the emperor’s son ‘Alemayehu Tewodros (1861–1879) were taken under the protection of the British, in accordance with the wishes of the dead emperor. The empress died on her way to the seashore, the royal prince was taken to Britain, and died there a decade later. He was buried at Windsor Castle.

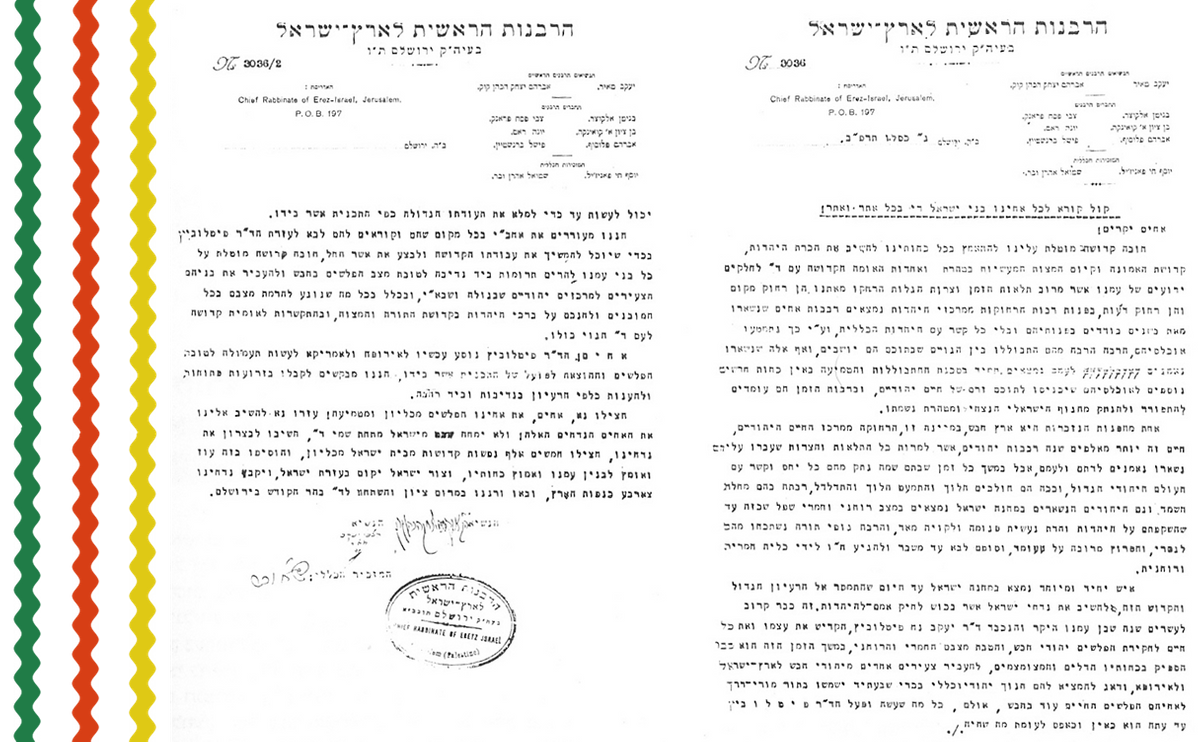

Ge‘ez-Hebrew Correspondence

This is the background of the attempts to establish a correspondence between Beta Israel or Faras Muqra and the “Priests of the Hebrews” in Jerusalem. In these attempts were involved Abba Ṣagga’ Amlāk, one of the leaders of one of the Jewish or Judaizant grouping whose name was corrupted in Arabic and Hebrew transmissions, and one Ethiopian Jew who had arrived, in 1848, into the Land of Israel by the name of Daniel ben Hananiah, father of Moses. (The name Amlāk means “Grace of God” and probably refers to the Adoptionist doctrine according to which Jesus was the Son of God by Grace of adoption, and not in flesh.) The letter was sent through Steven van Bronckhorst, a missionary who had worked in Ethiopia, then in the Land of Israel.

The letter arrived in Jerusalem around 1864, was translated from Ge‘ez into Arabic, and from Arabic into Hebrew.

H. Zotenberg, “Un document sur les falachas,” Journal Asiatique, sixième série, 9 (1867): 265-268, published the Ge‘ez original which he got from Ya‘aqov Saphir (1822-1885). Saphir had published the letter twice, in two different Hebrew translations, which are different from the Hebrew translation made from an Arabic translation and found in the private archive of Abraham Firkowicz, who was in Jerusalem in 1864-65 while on his second travel to the Levant in search of ancient Jewish manuscripts. Firkowicz got his copy of the translation from Arabic, which seems to be a crude draft, from Ya‘aqov Saphir.

Ya‘aqov Saphir

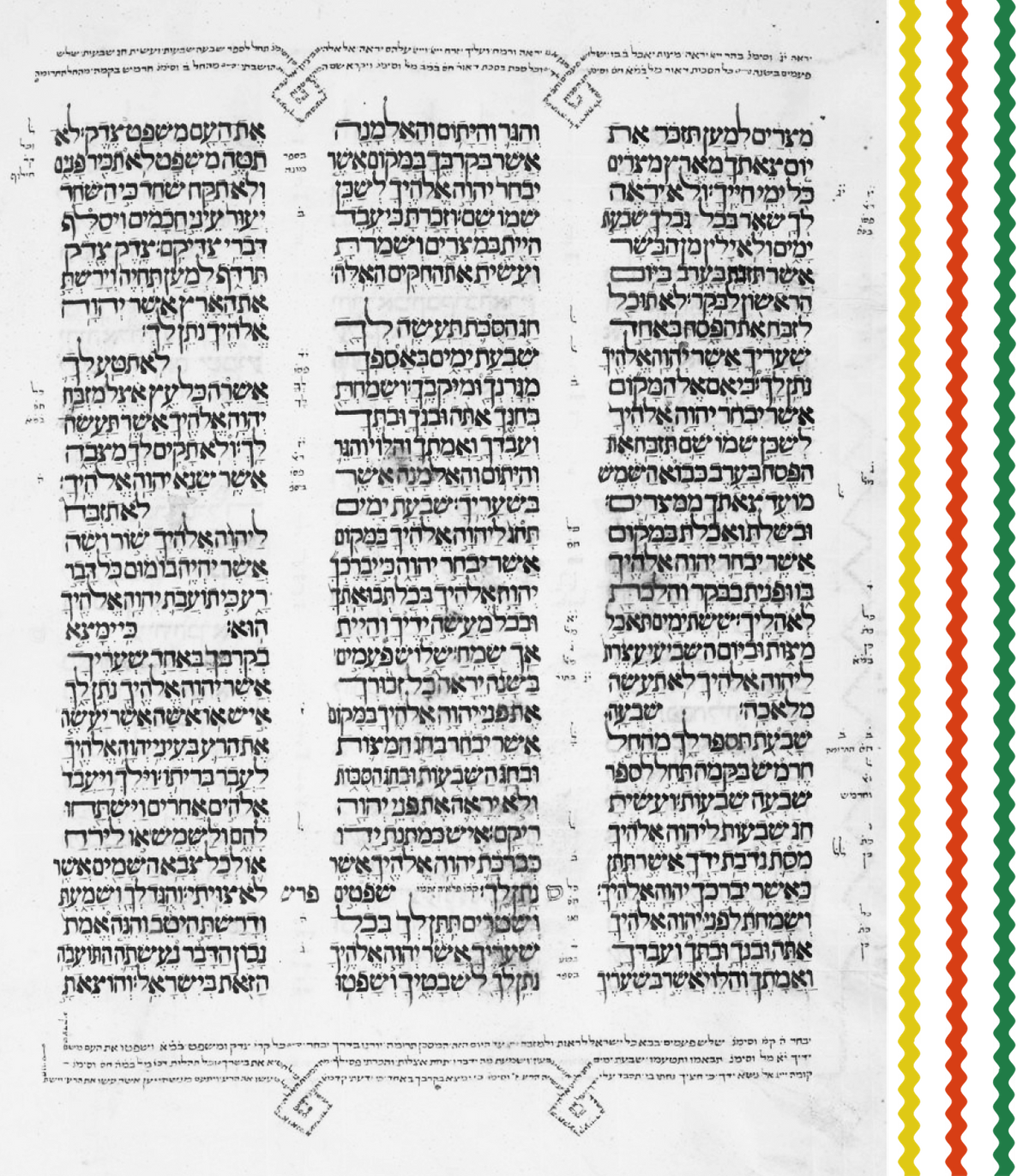

Saphir was sent in 1859 to schnorr funds in India and Australia for building what will be known as Ḥurvah Synagogue in Jerusalem. He was robbed of his money while on the ship in the Red Sea and was forcibly disembarked in Aden. This is how he met Jews of Yemen; he was especially charmed by those living in inner Yemen, in ḥadrei Teiman (‘Adani Jews were already materialistic stock making money and quickly Westernizing in the British coaling station, the process propelled a decade later, after the Suez Canal opened in 1869). In Yemen Saphir collected many ancient manuscripts. He was able to continue his journey to Bombay where he met Marathi-speaking Benei Israel on whom Saphir wrote intently, then he traveled to Dutch East India, then made his way to Australia, and in 1864 he came back to Jerusalem via Yemen. In his book Eben Saphir (1864-66) he told about his travels, discoveries, Jewish manuscripts he saw and collected, and on “exotic” Jewish communities he met, including the Jews of what we now call Ethiopia. Among the books he brought from Yemen was what is now BnF 1314-1315, or Al-Ousta Codices, a 14th- or 15th-century illuminated codex in two volumes of all the 24 books of the Bible written apparently in Spain.

The book was brought to Egypt and then to Yemen by a family of Yemeni communal leaders and royal officials of Iraqi origin.

Saphir mentioned that after he had shown Abraham Firkowicz in Jerusalem some of his Yemeni books, Firkowicz used to return them to Saphir with Firkowicz’s “corrections”! So, apparently, Firkowicz got the letter from Abyssinia from Saphir.

The Hebrew versions were published several times, two of them by Saphir, by Rabbi Menachem Waldman, and by myself. Names are distorted in the Hebrew versions made from Arabic then “polished.”

The letter says:

Written in the Abyssinian land, from Abba Ṣagga’ / Sharga’, to Joseph Tha’tubah, (a reply to the letter?) written by Daniel Wan / Ben Daniel.

Blessed be God of Israel God of every flesh and every spirit, let this letter written by Abba Ṣagga’ / Sharga’ reach the hands of the Great Priest of Jerusalem, to all the Hebrews; let this letter reach you by the effort of our brother *Borckhorst.

Peace be upon you. The first letter from Daniel ben Hananiah, father of Moses. Time had already come for us to return to where you are, to our land as well to the Holy Land and to our holy city of Jerusalem. We are miserable / poor people, without any priest / judge or prophet. If the time has come indeed, please and please, send ye us a letter about this matter, so it could arrive us, because you are better (placed) than we. Tell us what should be and what will be in the next days. As for us, there is great confusion in our midst, because people arose among us who said it was time to separate ourselves from the Messiahnists (Arabic for Christians; Ge’ez: Christians), so that we could go to your place, to the cities of Jerusalem, to join your brethren, and to offer sacrifices to God, the God of Israel, in the Holy Land, and thou, Oh Bronckhorst, Man of God, on behest of love that we love thee, please try to make sure that our brethren would send us the good reply to this letter!

Peace be upon you Hebrew brothers. Peace be upon you who are in the Torah / Land that God gave to Moses His Slave on Mt Sinai. I, Abba Sharga’ / Ṣagga’ [Amlāk], had already sent you this second letter in the year 7,354 / 5,467 from the existence of the world, in the second month.

[Note: the first date is Anno Mundi according to one of the systems current in Ethiopia in the 19th century, the second date is the starting point BC of this system; the current (2020/1) year in Ethiopia is 2013.]

Joseph Halévy and Ḥabshush

In the wake of Napier’s Abyssinian military expedition, Joseph Halévy (1827–1917), an Ottoman rabbi, was sent in 1867/8 by the Alliance israélite universelle to Abyssinia to study the whereabouts of the Jews of Abyssinia where he worked between December 1867 till March 1868. Jews of Abyssinia asked Joseph Halévy to take with him to Europe or to Jerusalem a boy, Daniel Edhanan, a relative of Abba Jeremiah. Daniel was not accepted by the Alliance’s schools in France and he died in Alexandria on his way back to Ethiopia in 1869. Halévy’s report of his mission was highly esteemed by Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (though some claimed that never visited Ethiopia and Daniel was a Black slave he bought in Egypt).

However, Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres sent Halévy to study the antiquities and the Jews of Yemen in 1869-70. In Yemen, Halévy was highly assisted by one Ḥayyim Ḥabshush, who learned from Halévy to copy Sabaean inscriptions. In his diaries, Halévy never mentioned Ḥabshush by name, and were it not that we have Ḥabshush’s own version, in Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic, about his travels with Halévy, we would never have known his name.

Ḥabshush’s book was published: Mas‘ot Ḥabshush (מסעות חבשוש) The travels of R’ Hayyim ben Yahya alongside Joseph Halévy in Yemen and the life of Arabs and Jews living there (edited by S.D. Goitein), 1941).

Meanwhile in France, the siege of Paris and La Commune de Paris destroyed Halévy’s Ethiopian collections. Later he published Essai sur la langue agaou. Le Dialecte des Falachas (Juifs d’Abyssinie), Paris, Maisonneuve, 1873, the Ge‘ez text with his Hebrew translation of the Falasha prayers, Prières des Falachas in 1877, and Ta‘azaze Sanbat, in 1902, and since 1879 he taught Ge‘ez in the École pratique des hautes études.

Giuseppe Sapeto and other Italians, and Menelik II

Giuseppe Sapeto (1811-1895), an Italian Lazarist missionary, worked in Lebanon and Egypt, and between 1837-1858 in Northern Ethiopia. When the Suez Canal was completed in 1869, he suggested establishment of a coaling station for Italia in Eritrea. In the autumn of 1869 he was sent by the Italian government to the Red Sea to choose a suitable port. By March 1870, an Italian shipping company acquired territory at Assab Bay. The territory was claimed by the Khedivate of Egypt, a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. The Egyptian defeats in the Abyssinian–Egyptian War (1874-1876), the Mahdi’s rule in the Sudan (1881–1885) led to vacuum in Eritrea, and the highlands along the Eritrean coast were ceded by King Menelik of Shewa (a southern Ethiopian kingdom), the future Emperor Menelik II (r. 1889–1913), to Italy in the Treaty of Uccialli in exchange for guarantees of financial assistance and continuing access to European arms and ammunition.

But before that, in 1883 and then in 1889, a Russian Cossack and a Russian monk, Paissiy, tried to establish a Free Cossack Country in Abyssinia (now Djibouti), “New Moscow.” In 1889-9 and 1891-2, another Cossack, Lieutenant Mashkov, visited Abyssinia, was accepted by Menelik II, and brought 350 rifles.

This was how modern Ethiopia was born.

Dan Shapira is an interdisciplinary historian and philologist at Bar-Ilan University. He is working currently on medieval and early modern Jewish minority communities, the Crimea, and the Khazars.