Was Elia R. Karmona the Sholem Aleichem of Ladino?

The prolific author wrote stories with a satirist’s keen eye, but remains relatively unknown today

In the Sephardic diaspora cities of Istanbul and Seattle, the history of Ladino is being rewritten as new discoveries surface from dusty piles of periodicals and books in Arabic, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin scripts among Ottoman ephemera, including many trans-Atlantic steamship tickets. If Sholem Aleichem is a measure of Yiddish as a literary—and in that sense an international—cross-cultural language, based on the global popularity of theatrical adaptations of his short story “Tevye the Dairyman,” then Elia R. Karmona could be an apt candidate by which to assess the universal humanism of Ladino’s expression in writing, and a source to begin reckoning with it as literature.

This April, Chicago University Press publishes Sephardic Trajectories: Archives, Objects, and the Ottoman Jewish Past in the United States, with scholarly contributions from Ty Alhadeff at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies of the University of Washington, and Kerem Tınaz of Koç University in Istanbul. Initially produced to accompany an exhibition of heirloom objects tracing the history of remembrance and preservation, Sephardic Trajectories is a landmark demonstration of international collaboration between Turkey and the United States, advancing Jewish historiography by integrating the latest digital technology to copy, itemize, and disseminate Ladino literature. Sephardic Trajectories is not a sole beneficiary of state or foundational backing, but a collective labor of love involving over 80 community members from organizations as diverse as Koç University’s Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations (ANAMED) in downtown Istanbul and the Sephardic congregation of Bikur Holim in Seattle. The collections of Sephardic material, largely originating from printers and manufacturers in the Ottoman Empire, currently housed at the University of Washington, exemplifies the potential of community-led archives.

It was the poverty afflicting Ottoman Jewish publishers that led Karmona to serialize popular fiction, beginning with folkloric konsejikas (Ladino for “bits of advice”), as told by his mother. According to Laurent Mignon, professor of Turkish at the University of Oxford, writing in Sephardic Trajectories, it was arguably his Jewish mother in Istanbul, and her storytelling, which prompted modernism in Ladino literature. Her succinct morality tales struck a chord with the peculiarly entrepreneurial and creative editorial ear of Karmona. Her yarns sold, and soon he had the finances to set up his own printing press.

As soon as Karmona earned enough money, he worked with the Greek printer Alexandros Numismatidis. When his mother’s tales tapered off, Karmona went to Armenian theater director Mardiros Minakyan for material. Minakyan and Ladino translators promoted Shakespeare and the latest Western literature in Ottoman Turkey.

Whether onstage, on the street, or at home, Ladino texts were written with the knowledge that most would listen to them recited. As Mignon explains: “The Ottoman Turkish novelist, just like Eliya Karmona and other Ladino novelists, would have been conscious of the fact that their books were read aloud, and in many ways performed, and embraced a style that kept the listeners’ attention continuously, taking them by the hand through the many exploits of their heroes and, indeed, heroines.” Mignon goes on to compare Karmona to canonical Turkish novelists Ahmet Midhat Efendi and Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar. While readers of Ladino enjoyed Karmona’s originality, they also read Gallicized translations of Emile Zola’s Nantas, published in Cairo in 1904 by M. Menashe, who Mignon asserted, “was attempting to establish a literary language” out of Ladino.

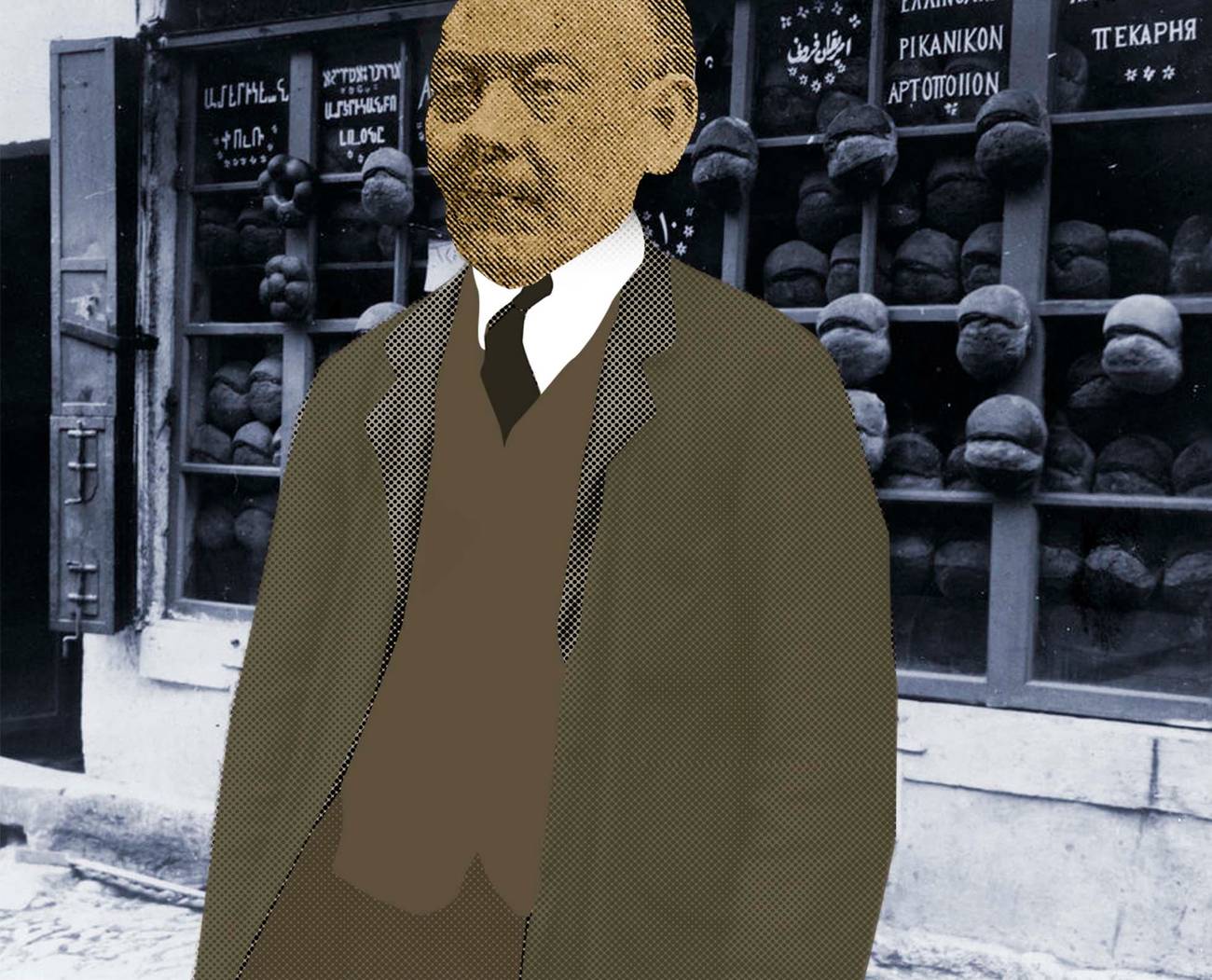

Karmona, who was born in Istanbul in 1869, wrote about Ottoman Jewish immigration to Europe and America, yet remained within the realm of the sultan throughout his career as a newspaperman and novelist in the heyday of Ottoman publishing, serializing over 50 books of fiction in his satirical broadsheet, El Jugeton (translated as The Big Clown, or The Joker).

The first issue of El Jugeton came out in 1909 following the Young Turk Revolution, which reinstated constitutional rule during the despotic Hamidian era, an infamous chapter in Ottoman history when Abdul Hamid II provoked unprecedented violence against Christians, ultimately disintegrating Ottoman multiculturalism and setting the stage for WWI.

In a recent compilation of research and writing titled “From Our Fathers’ Newspapers,” Turkish translators Ninet Bivas and Leon Keribar printed the brief, picaresque autobiography of Elia R. Karmona in Turkish, Ladino, and English. On the 18th anniversary of El Jugeton, Karmona wrote “How Eliya Karmona Was Born” with his characteristic levity. His autobiography details his trials as a working Ottoman Jewish journalist in Cairo and Istanbul on the fringes of Western society. He was like Jacob Riis, recounting economic hardship firsthand with a muckraking sensibility, yet Karmona’s proto-metafiction adds a hefty dose of Jewish humor.

“How Eliya Karmona Was Born” chronicles the author’s work history, beginning with his birth on Oct. 21, 1869, or 16 Heshvan 5630: “Old women say that Heshvan is not a lucky month and this is probably true, since throughout my life I had to face an unending series of problems, and miseries that you are about to read in the present story.” Karmona was the coddled, only son of a Jewish patriarch whose family wealth had declined since the early 19th-century reign of Mahmud II, when the sultan strangled their ancestor Behor Karmona. After a short-lived ordeal in the stock market, his father became a tramway ticket seller and sent him to Talmud Torah school in the waterfront quarter of Ortaköy.

While the teenage Karmona learned French at a newly opened Alliance school in Ortaköy, where the Tree of Life synagogue still stands along its busiest thoroughfare, his father landed him a job teaching French, the world’s lingua franca, to the children of Abdul Hamid’s grand vizier. But he was still learning French himself, and soon fell out with the palace. He became one of those pesky children who continue to roam the streets of Istanbul, most now from Roma families, selling matches and tissues for spare change. But his mother would not see him, a Karmona, as a lowly street peddler. His forebears had monopolized Ottoman imperial banking and walked with the Sabbatai Zevi.

It was by chance that one of Karmona’s powerful relatives saw him arguing in the street with an Iranian patron over 5 kurush (cents). While at the Tree of Life synagogue in Ortakoy, David Karmona caught wind of the embarrassing, public pickle. The young Karmona answered his call, came to see him blushing, and got an earful about family honor.

In 1877, David Karmona was one of two Jewish senators in the first Turkish parliament. The son of Behor Yitzhak, assassinated by Sultan Mahmud II, his cousin was Rafael Karmona, Elia’s father. David Effendi, as he was respectfully titled, got Elia a job at El Tyempo, one of the first Ottoman Jewish newspapers, founded in 1872, launching his career in journalism. Karmona worked as a printer for Moshe Kohen and David Ben Shelomo out of their workshop in the old Italian colony of Galata. While friendly, they underpaid despite promoting him to chief typographer when Shelomo left to work for a new magazine, El Enstruktor. Karmona ran into the philanthropist Baron Hirsch the day he quit.

He used his street smarts to tease out the route of the wealthy man’s carriage, and catching him by Dolmabahçe Palace, loaded a tray with cigarette papers, presenting himself as the poor Alliance student he was. “I am the son of an old Jewish family that had once been very rich but has now fallen into poverty,” he yelled out to the rich baron, who would only finance a quarter of the cost of a printing machine and typographic characters. Karmona started an itinerant garment trade in the hopes that he would one day afford the equipment. But walking the streets, shouting, “Clean Woolen Flannels” attracted a thief, and he was left penniless once again.

Karmona’s next short-lived venture was with a Jewish rag and rope merchant in Besiktas at the southern end of the Bosphorus not far from Elia’s childhood quarter of Ortakoy. Soon, he was a printer’s mechanic again. He wrote, “I met a beautiful girl who lived near our house” (he lived with his parents), and “it was she who taught me how to write love stories.”

On Dec. 4, 1893, the first night of Hanukkah, the father of his anonymous fiancée gave Karmona a lira at their home engagement. Soon after, he went to an all-night ball, and met a woman named Rosa. They danced the Cadrille and Lansey, and drank till dawn. “No one had the nerve to hug a girl and get nearer to her than squeezing her hand,” he wrote. He slept at work the next day, and was awoken by a courier carrying a letter from Rosa. She was the only child of a wealthy antique dealer, and gave him an English pound every time they parted. He was now in a bind, whether to stay true to his poor fiancée, who might be as good as orphaned after a bad engagement, or take the money and run with Rosa.

He loved Rosa. But he was a good Jewish boy, and listened to his mother, who implored him to respect the blessing of his initial promise, although she did not know of Rosa. Yet, to his relief, Rosa was married off. Love triangles and class struggles would frequent the pages of Karmona’s novels, as would the visitation of distant relatives in search of work.

Karmona’s first trip abroad was to Salonica, where his relative, Leon Karmona was said to be one of the richest men in that ancient sister city of Istanbul on Greece’s northern Aegean coast. “Listen my boy … all sounds appear nice to your ears from far away but when you get closer you get a headache,” Leon told Elia, and gave him 5 liras to live on for the month.

Not three weeks passed when he emigrated again over the Aegean Sea to Izmir on the Anatolian shore across from Athens. That year, he spent Rosh Hashanah of 5657 (1897) depressed, alone, over a bottle of raki and salad at an inn, missing his mother and fiancée when a fellow Jewish guest joined him. The young man turned out to be a murderer on the lam.

He dreamed of Paris. Jewish migrant workers, particularly Ladino-speaking Sephardim, commonly travel between Salonica, Izmir, Istanbul and Paris in Karmona’s novels, which also came to include Marseille and New York. In the world of Ottoman Jewry, money and love are bedmates who scrounge for each other in the depths of the late modern city’s dreaming.

But he would not realize the perennial migrant dream that was fin de siècle Paris, and instead returned to Istanbul to care for his ailing father. He swapped odd jobs with Armenians. “That year, many Armenians left Istanbul for political reasons,” he wrote, observing early signs of genocidal expulsion. He ended up hawking paper marionettes on the cobblestoned streets.

Another botched French teaching assignment led Karmona back to the home of his mother, where he embarked on his seventh job. He applied his typography skills to print his mother’s stories. That year, Theodor Herzl declared the right to a Jewish state. “That night, my mother told me a story about destiny and how what’s written in the skies cannot be changed in this world,” he wrote in his autobiography. “I knew that Jews who didn’t know either Turkish or French, would read Spanish. So I started to write in the popular language which both children and adults understood.”

With a loan of 200 francs from a colleague at the Alliance school, Karmona bought a set of Spanish typographic characters and worked in the printing workshop of Numismatidis. After profiting on his first three stories, he successfully bid on a book by a Salonica-based Jewish author, and his following editions included the story “The Two Orphans.”

“The Two Orphans” was among the initial eight stories that Karmona published inspired by his mother’s tales of domestic morality: “The Rich Juliette,” “The Passion for Money,” “The Gardener’s Daughter.” In his autobiography, he boasted of transforming the “small stories” of his mother into “full-length novels.”

One tale, corresponding to the titular motif of “The Two Orphans,” Sephardi diaspora historian Devi Mays has translated as “The Two Siblings.” It is just shy of 10,000 words, hardly a novel, or even novella by current standards, though a hearty piece of short fiction. Karmona printed it in El Jugeton in 5681 (1921-1922), selling it for 100 paras (cents of an Ottoman lira).

“The Two Siblings” is a post-WWI tragedy, recounting the untimely downfall of a man named Israel Behar, whose misfortune is reminiscent of Karmona’s. Largely set in the Galata district of Istanbul, it is a succinct picture of Istanbul’s Jewish communities and its internal class struggles reflecting the broader socioeconomic context of life in late Ottoman society. “The Two Siblings” relays the efforts of a “benevolent society of women” who come to the aid of single mothers like the fictive widow, Klara Behar.

Karmona was unique for writing about the world around him, as an Ottoman Jew, writing fiction about Ottoman Jewish life. He had a keen eye for young people. His stories are about the dilemmas of maturity, from childhood to adolescence, and into adulthood, as a metaphor for Jewish modernity.

“Karmona was known as an author and a satirist, a social commentator as well in the way that we could think of Sholem Aleichem,” said the translator Mays. “In his works he’s definitely grappling with the Jewish present by framing it in terms of a Jewish past in a way that you can see Sholem Aleichem also doing with Tevye and his daughters.”

Matt Alexander Hanson is an arts and culture journalist based in Istanbul.