German Jewish Women Resist the Nazis

Remembering and honoring the courageous, often deadly, fight to defy and defeat National Socialism

From the time Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, numbers of German Jews resisted his regime. Jewish women played a significant part in this opposition. Until recently, their role has been overlooked. German Jewish women who defied the Nazi regime took great risks in doing so. They faced sexual assault, sadistic torture, and being gruesomely executed, oftentimes by beheading. Despite these dangers, a number of them continued to defy Hitler’s government. Their acts of daring in the face of the Nazi plan to annihilate all Jews has received little scholarly or public attention.

These women deviated from the opinion that the role of women should only be “children, kitchen, church,” and they persisted in defying the Nazis. Against all odds, these women stayed true to their convictions. Without them, the Jewish resistance groups in Germany would have collapsed. Generally, the women were members of mixed groups of men and women. The only known Jewish group consisting entirely of women was active in and around Berlin, which contained 160,000 Jews, out of a total German Jewish population of 505,000.

Marion A. Kaplan, in her book Between Dignity and Despair: Jewish Life in Nazi Germany (1998), offers an incisive portrait of Jewish resistance to the Nazi regime. She explains that hiding from the Nazis was frequently an isolated move by Jewish individuals, or by Jews from the same family. In all cases, they tried to support one another. Those Jews who were fugitives in Berlin tried to relieve their isolation by meeting in cafés and by setting up a Jewish grapevine. They used the grapevine to warn each other of the locations of persons who wanted to catch them. And they traded information about where to get false identity cards and about border runners who were willing and able to smuggle Jews out of Germany. Some of the women formed groups that augmented those of Jews already in hiding, and who had shelters and false documents prepared for other Jews. Berlin was an ideal place for this kind of activity, since Jews there were able to connect with one another fairly easily. Jews who had to shift from village to village or hide in small towns had few other Jews with whom to communicate.

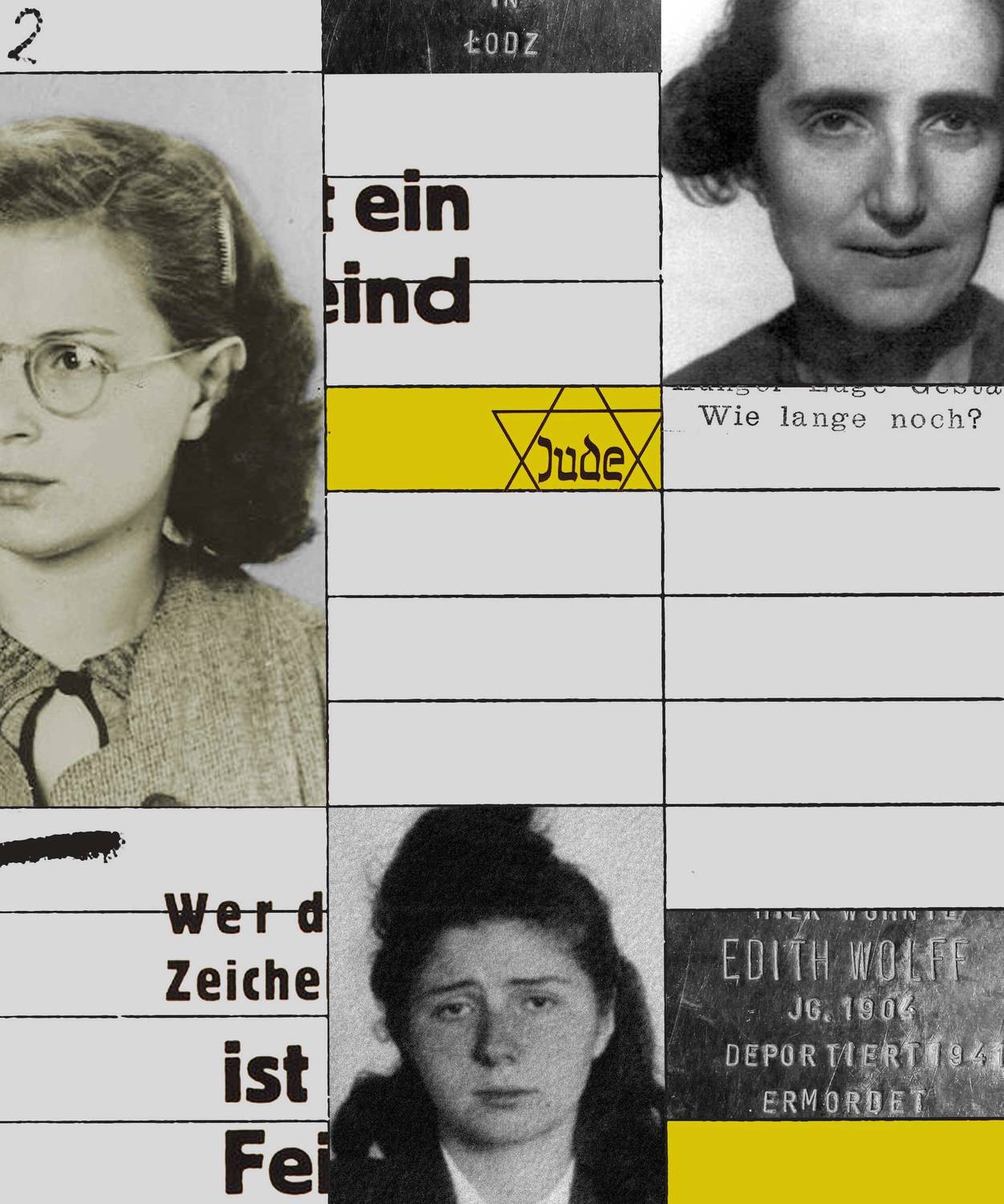

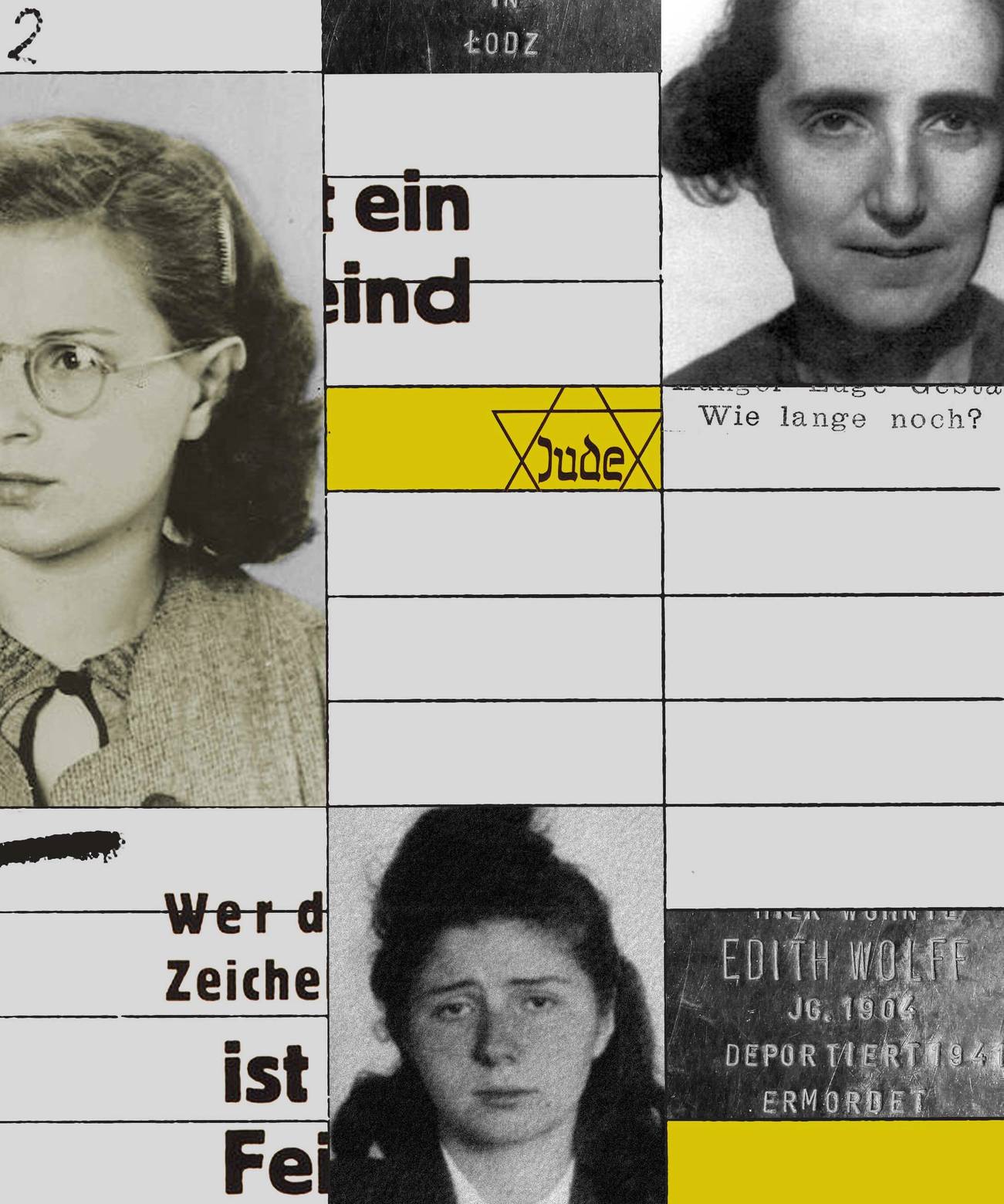

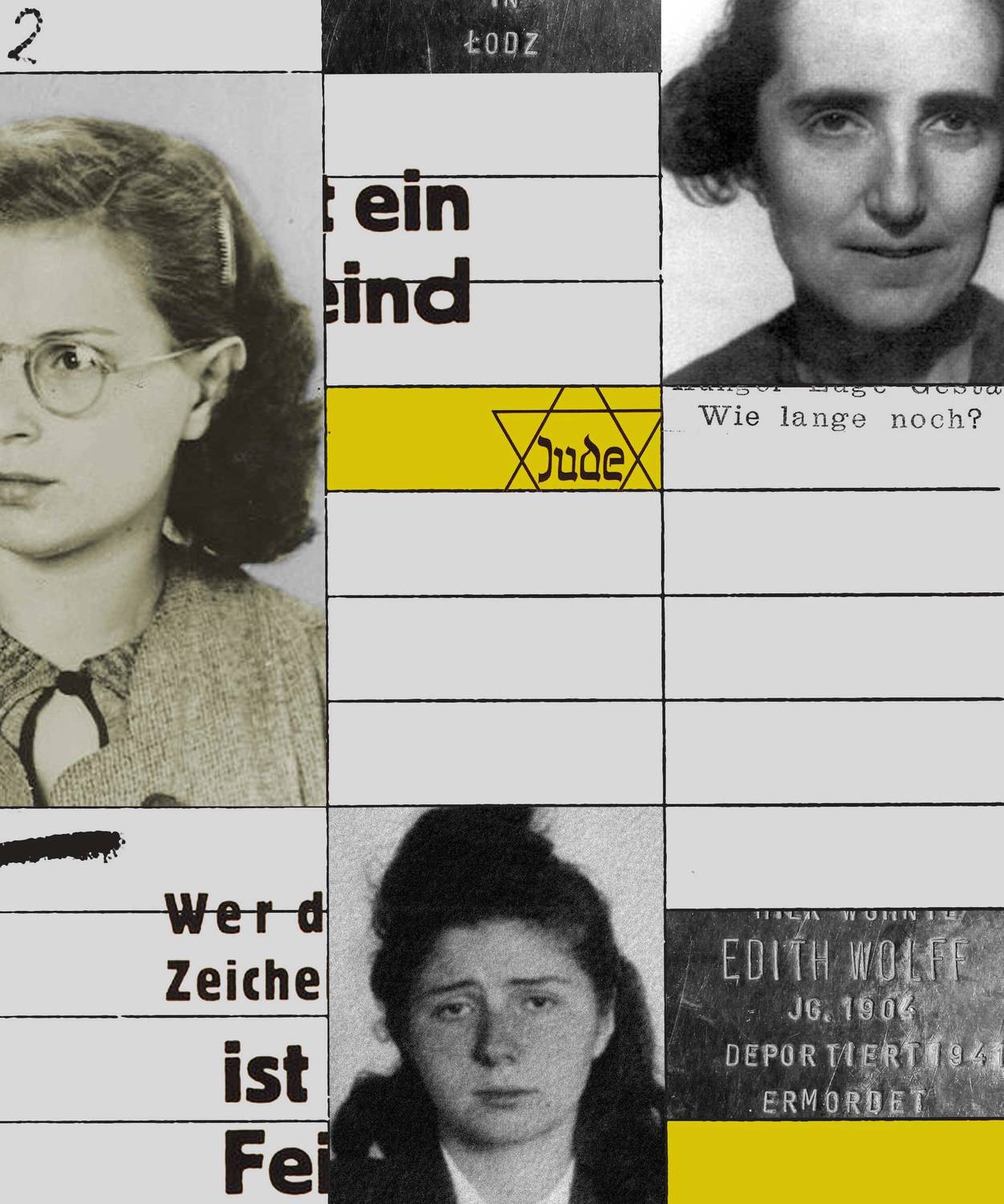

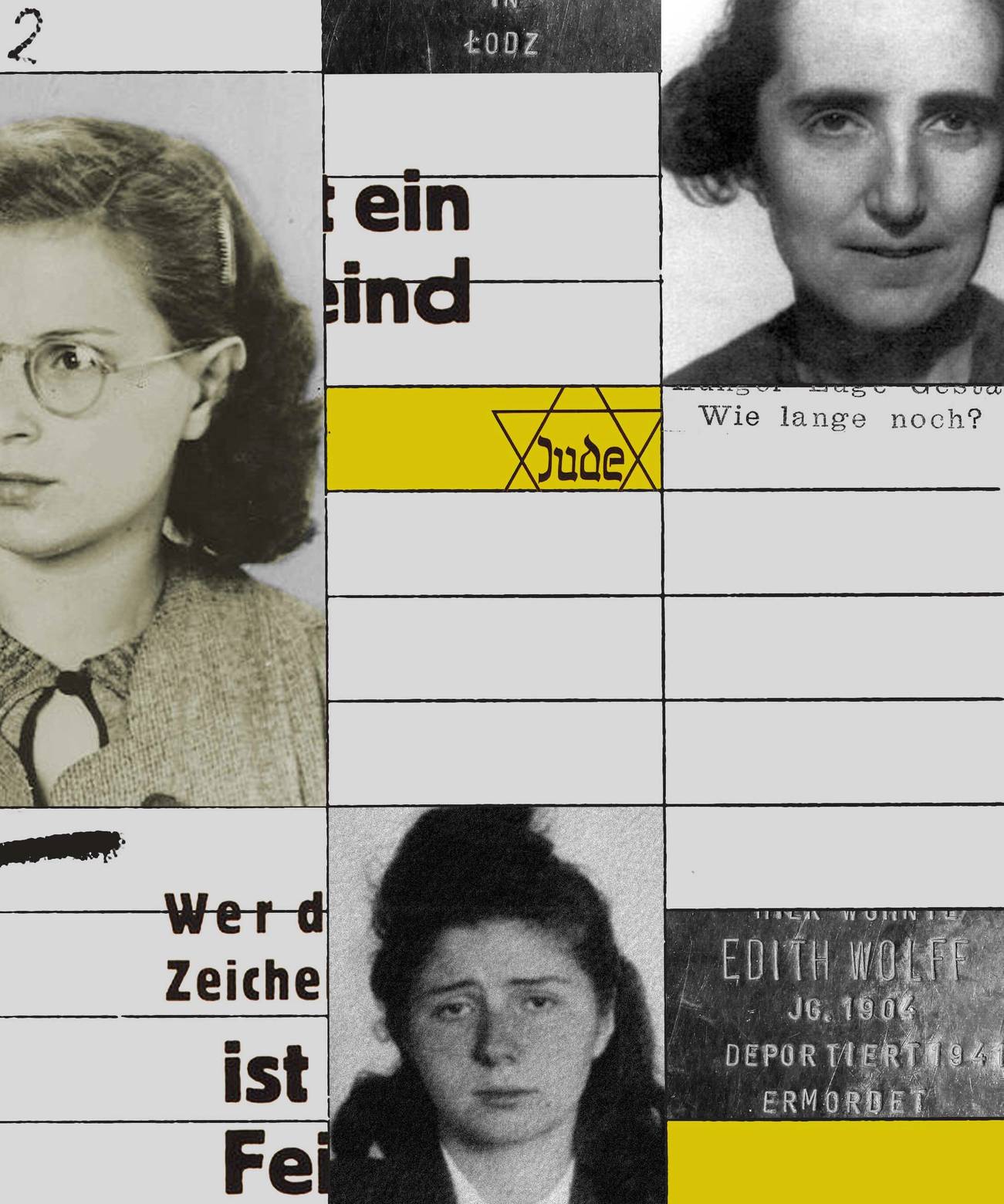

The Chug Chaluzi (Pioneer Circle) was one such German Jewish resistance group. Edith Wolff, a young woman who had been brought up as a Protestant, but turned to Judaism and Zionism in protest against the National Socialists, organized the group in her home together with her boyfriend, Jizchak Schwersenz, a teacher, Zionist, and youth leader, on Feb. 27, 1943. This was the same day that all Jewish forced laborers were arrested and most of them deported. The group originally had 11 members, all of whom had been members of Zionist youth groups. Between 1943 and 1945, the group supported an estimated 50 Jews in hiding. Most of them lived illegally in Berlin. Group members helped each other obtain food, false ID cards, and places to stay. At the end of the war, Chug Chaluzi had approximately 40 members.

As much as possible, they continued their youth group activities, which included Hebrew lessons, illegal visits to the theater, outings in the woods, and celebrations of the Jewish holidays. Its recognized leader was Schwersenz who lived under the assumed name Ernst Hallermann in Berlin from August 1942 until February 1944, when he fled to Switzerland. After his escape, Gad Beck became the leader of the group.

Beck had been born Gerhard Beck in Berlin along with his twin sister, Margot. His father was born Jewish, and his German mother, originally a Protestant, had converted to Judaism. As a person of partial Jewish ancestry (a Mischling in Nazi terminology), he was not deported with other German Jews. Instead, he remained in Berlin. Beck joined an underground effort to supply food and hiding places to Jews escaping to neutral Switzerland.

Beck remained its leader until early 1945, when a Jewish spy for the Gestapo betrayed him and some of his underground friends. He was subsequently interrogated and interned in a Jewish transit camp in Berlin. His parents and sister survived the war thanks to help from their Christian relatives on his mother’s side. Beck survived the war and helped organize efforts to bring Jewish Holocaust survivors to Israel. He himself emigrated in 1947. In 1979 he returned to Berlin where he was the director of the Jewish Adult Education Center. He died in Berlin in 2012.

Although the Nuremberg Race Laws classified Edith Wolff as a “First Degree Mischlinge,” a person of mixed Jewish and non-Jewish blood, she willingly exposed herself to peril because she sustained contacts with persecuted Jews and helped many of them to escape. She maximized the risk to herself by stubbornly leaving her own anti-Nazi leaflets in library books, telephone booths, and other public places. She also pasted anti-Nazi slogans wherever she could and mailed threatening postcards to Nazi bureaucrats.

When the first Berlin Jews were deported in the autumn of 1941, she decided to take part in organized forms of resistance. She found ways to help young Jews and her friends to go underground or to leave the country. She persuaded a reluctant Jizchak Schwersenz to go underground himself. She assured him, “Only in this way can you save the children.” Wolff and he began to prepare to save children and young people from deportations.

In 1942, Schwersenz received news about the “chimney” in Birkenau and the fate of Jews who had been deported there. He also learned about Auschwitz by listening to the BBC. He followed Wolff’s advice and went into hiding in Berlin in August 1942.

German Jewish women who defied the Nazi regime took great risks in doing so. They faced sexual assault, sadistic torture, and being gruesomely executed, oftentimes by beheading.

In the meanwhile, Edith Wolff actively prepared to save children and young people from deportations. She used the Chug Chaluzi group and coordinated help for Jews attempting to escape. This group consisted primarily of young, mainly unmarried persons bound by ideology and friendship, and committed to common goals. The Jewish activists of political movements and of the anti-Nazi resistance were recruited from just such a milieu.

The group was the only known underground Zionist group of its kind in Germany. It survived for more than a year. In addition to its rescue activities, the group prayed for deported parents and friends, but recited the traditional Mourner’s Kaddish only for those whom the Nazis had murdered before they had been deported.

Wolff viewed saving Jewish lives as a form of political resistance. “We’re combating Hitler with every life we save,” she said. She was eventually caught, but miraculously survived 18 concentration camps and prisons. She later immigrated to Israel, where she died in Haifa in 1997.

A plaque to Edith Wolff and Chug Chaluzi was installed on Bundesallee 79, the street where the Chug Chaluzi was founded. It reads: “Lived in this house: Edith Wolff, called ‘Ewo’ (1904-1997). Grew up in a Christian-Jewish family home and founded the youth resistance group here on February 27, 1943 with Jizchak Schwersenz and other submerged Jewish friends. Chug Chaluzi. On June 19, 1943, Ewo was arrested and survived 18 concentration camps and prisons.”

Chug Chaluzi members sought to develop Jewish consciousness, to strengthen Jewish solidarity, and to prepare its members for a Jewish life in Palestine after the war. It divided its illegal work between physical survival and cultural survival.

Members met regularly, often daily, to exchange information and to organize meals and lodgings for each other. They also attended public theaters, concerts, operas, and movies. In the summer they met in parks, and in the winter met in a variety of hiding places. Bombings did not stop them, and they would gather one hour after the all-clear signal. Their cultural activities had a socialist and Zionist orientation and included study groups, religious practice, and visits to cultural events in Berlin. These activities served as a kind of intellectual passive resistance.

So as not to draw attention to themselves, they rarely went anywhere in groups of more than two. And if they traveled in larger groups, they pretended not to know each other. When the entire group met, only two people would arrive at the destination every 15 minutes.

Their weekly schedule included hiking and sports on Sundays, attending Berlin cultural events on Mondays, studying Hebrew or English on Tuesdays, discussing Palestine and Zionist history on Wednesdays, analyzing the Hebrew Bible on Thursdays, and meeting and general discussions on Friday. They planned their most important meetings for Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, when they prepared for the cultural event they would attend the following week. At these sessions, they would read the opera or play they planned to see. They also read Jewish history and Jewish literature on the Sabbath. Then they engaged in political discussions and themes of general interest. They ended the Sabbath with the traditional Havdalah ceremony (that differentiates between the Sabbath and the work day) using a flashlight, leaves, and a taste of cognac, in place of the customary candle, spices, and wine.

Members of the Chug Chaluzi had to guess the dates for the Jewish holidays, since the last Jewish calendar they had was for the year 5700 (1939-1940). When the holidays arrived, they decorated whatever meeting place they had chosen with flowers and candles. Then, in place of the challah, they shared some plain war rolls. Sometimes they prayed together, although they could not hold actual services. Despite these difficulties, most members of the group’s inner circle survived, likely because of help they received from non-Jews, particularly those connected to the communist resistance movement. They also received financial aid from Zionist organizations abroad. They exuded a great deal of youthful nerve and brashness.

Group member Liane Berkowitz was born on Aug. 7, 1923, in Berlin. She was the daughter of the Russian orchestra conductor Viktor Vasilyev, who had fled the Soviet Union. After the death of her father in 1930, she was adopted by Henry Berkowitz and took his name. She spoke fluent Russian and was educated in private schools. She participated along with others in an action against the anti-Soviet propaganda exhibition, The Soviet Paradise, in August 1942. She was arrested in September and sentenced to death by the Reich Court Martial on Jan. 18, 1943. On April 12, 1943, she gave birth to her daughter Irene in the women’s prison in Berlin. The baby was cared for by Liane’s grandmother. Later the child was killed by the Nazis. Hitler rejected a clemency plea to spare her and Liane was executed by the Nazis in August 1943.

Killing Jewish children was part of Nazi policy. In an Oct. 8, 1943, speech by Heinrich Himmler to SS members, he explained that the Jewish children must be killed lest they grow up to avenge what the Germans were doing to the Jews. “I did not feel that I had the right to exterminate the men, that is to murder them, or have them murdered, and then allow their children to grow into avengers, threatening our sons and grandchildren. A fateful decision had to be made: This people had to vanish from the earth.” This is what German Jews were up against. They had no choice but to resist.

Cora Berliner was another bold German Jewish resister. She was born in 1890 and earned a doctorate in mathematics and law at Heidelberg University in 1916. She later served as a managing director and chair of the board of the Federation of Jewish Youth Associations in Heidelberg. In 1923 she joined the civil service and managed the Reich Economics Office. In 1930 she became a professor of economics at the Institute for Vocational Education in Berlin. As a Jew, she was dismissed from the civil service in 1933. She then went on to work for the Reich Association of Jews in Germany. She also headed its emigration department. As the vice chairman of the Jewish Women’s Association, she was involved in assisting Jewish women and girls to emigrate from Germany. On June 24, 1942, she was deported in the so-called “punishment transport” to Minsk in Belarus. When she arrived, the Germans lined her up with other Jews in front of a pit outside the city and shot them all.

The majority of Jewish women who resisted National Socialism and the Nazi regime came from the political left. Sala Rosenbaum-Kochmann, who was a leading figure in the pro-communist Herbert Baum group in Berlin, exemplifies this.

The Baum group was a circle of young Jewish resisters to National Socialism and the Nazi regime who were living in Berlin and congregated around Herbert Baum. Baum was active in the German Jewish youth movement and in Zionist youth leagues, before becoming involved in the outlawed Berlin communist youth organization. Baum recruited most of the members of his resistance group from young Jews who, like himself, were employed in the Siemens plant doing forced labor. Up until June 1941 the group engaged only in internal indoctrination at the plant. The group did not begin activities, such as printing and distributing leaflets, until after the start of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union.

Kochmann encouraged young Jews to stick together in conditions of increasing isolation and exclusion under the Nazi regime. She was one of the Baum group members who participated in a May 1942 arson attack against a Nazi propaganda exhibit sponsored by Joseph Goebbels in Berlin. They, together with a group of non-Jewish communists, planted incendiary bombs in the exhibition. The fire was quickly extinguished and, after a few days, most members had been arrested by the Gestapo. In March and September of 1943, 22 members of Baum’s group were tried and executed. By then, the vast majority of German Jews had already been deported, murdered, or interned at Theresienstadt.

Kochmann was captured shortly after this event. She was condemned at a swift trial and executed the morning of Aug. 18, 1942. Tipped off by an acquaintance, her husband, Martin Kochmann, managed to evade his Nazi pursuers until October 1942, when he was arrested by the Gestapo and executed.

The resister Marianne Prager-Joachim was born in November 1921 in Berlin. She completed her schooling and trained as a caregiver for children at the city’s Jewish orphanage. In the summer of 1940, she was forced to give up this profession to become an agricultural laborer. She married Heinz Joachim in August 1941. The Germans classified both her parents as Jewish. Her newly acquired father-in-law was classified as Jewish, but her mother-in-law was not. After her marriage, she was sent back to Berlin where she worked in an automobile parts plant.

When she returned to Berlin, she and her husband became members of the Baum resistance group. At night Marianne and Heinz held secret weekly meetings at their apartment with comrades to plan whatever actions they might take, however small, to undermine the Nazi government. As a result of these meetings, the group embarked on a series of actions against the Nazi regime. They printed leaflets begging people to join their struggle against the Nazis. They wrote letters to German doctors describing the real conditions suffered by German soldiers at the front. Defying the curfew, they painted anti-Hitler slogans on fences and walls around Berlin. In the factory, Baum constantly encouraged Jewish workers to slow down production and to sabotage equipment.

On May 18, 1942, at 8 o’clock in the evening, three members of the Baum group carried out an attack against the anti-Soviet exhibition sponsored by Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s minister of propaganda. They carried briefcases containing homemade explosives into the first exhibition tent. Marianne circulated in the tent, serving as one of the lookouts. Herbert’s bomb burst into flames and he fled the exhibit. All of them left the exhibit 90 minutes after they had arrived.

Firefighters quickly put out the flames from Joachim’s bomb and cordoned off the burned area. The exhibit opened as usual the next day and attracted large crowds. The Nazi-controlled newspapers never mentioned the incident.

A dragnet was organized to find the culprits. Four days later, 11 people, including Herbert Baum and his wife were arrested. Marianne and Heinz avoided arrest until June 9. Another 48 people were also apprehended, some barely linked to any group.

Although tortured with beatings and punches to the face, many still remained defiant. Lotte Rotholz, who had been badly beaten, said, “One must utilize every opportunity to fight against the present regime.” Lise Lesèvre, another Jewish resister who belonged to an anti-Nazi group, was arrested by the Gestapo in March 1944, while she carried a letter intended for another resistance leader. She later related how she was interrogated for 19 days and tortured on nine of them.

First, she was hung up by handcuffs with spikes inside them and beaten with a rubber bar. Next, she was ordered to strip naked and get into a tub filled with freezing water. Her legs were tied to a bar across the tub and a chain attached to the bar was yanked to pull her underwater. She said, “I wanted to drink to drown myself quickly. But I wasn’t able to do it. I did not say or tell them anything. After 19 days of interrogation, they put me in a cell. They would walk by carrying the bodies of tortured people. They would look at their faces to see if it was a Jew. If they saw it was a Jew, someone would crush the face with his heel.”

During her last interrogation, she was ordered to lie flat on a chair. She was then struck on the back with a spiked ball attached to a chain that broke her vertebrae. She was condemned to death by a German military tribunal for “terrorism.” But she was placed in the wrong cell and deported instead to the Ravensbruck concentration camp where she survived the war. Her husband and son did not. They had been deported and murdered.

Herbert Baum and Heinz Joachim were arrested at work on May 22, 1942. Two weeks later Marianne was arrested at her home and imprisoned. In a summary trial lasting only one day, she was sentenced to death. She was kept in her cell for eight months before her execution and was unaware that her husband had already been killed. During her time in prison she was allowed to send and receive one letter per month. She sent letters to her parents in November and December 1942, and one letter in January 1943 and March 1943. These letters have been made available online by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., and provide some indication of her state of mind at the time. While in prison, she learned that her husband, Heinz, had been executed by the Germans. She described this discovery to his parents as the “cruelest blow of fate.”

She knew that she would be killed. She informed her parents-in-law of her impending death and mentioned to them that she had her remaining things sent to them. She believed that her husband’s parents had a better chance of surviving the Nazi nightmare because his mother was not Jewish. The 21-year-old Marianne was executed by decapitation in Berlin’s Plotzensee penitentiary on March 4, 1943. Her younger sister had managed to escape to England before the war.

Later in March 1943, her parents were deported to Auschwitz. From there they were transported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp where they were murdered. Her husband Heinz’s father died in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp at the end of 1944. His mother, Anna, was not Jewish and survived to outlive the Nazi regime.

Marianne wrote to her parents from jail, “Think of all the songs we all sang together, all is fine! Live well, my beloved parents.”

Over the next 18 months, 32 members and supporters of Baum’s group and other Jewish youth groups were murdered. Sixteen were 23 years old or younger.

The Nazis retaliated against the families of those involved. Marianne’s mother was shipped off to Auschwitz. Her father was sent to Theresienstadt. Two hundred fifty Jews, who had nothing to do with the bombings, were shot. Another 250 Jews were murdered in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

A monument to those executed stands at the western entrance to Berlin’s Weissensee Jewish Cemetery.

Robert Rockaway is professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University, and the author of But He Was Good to His Mother: The Lives and Crimes of Jewish Gangsters.