God’s Daily Schedule

How does He spend his divine time?

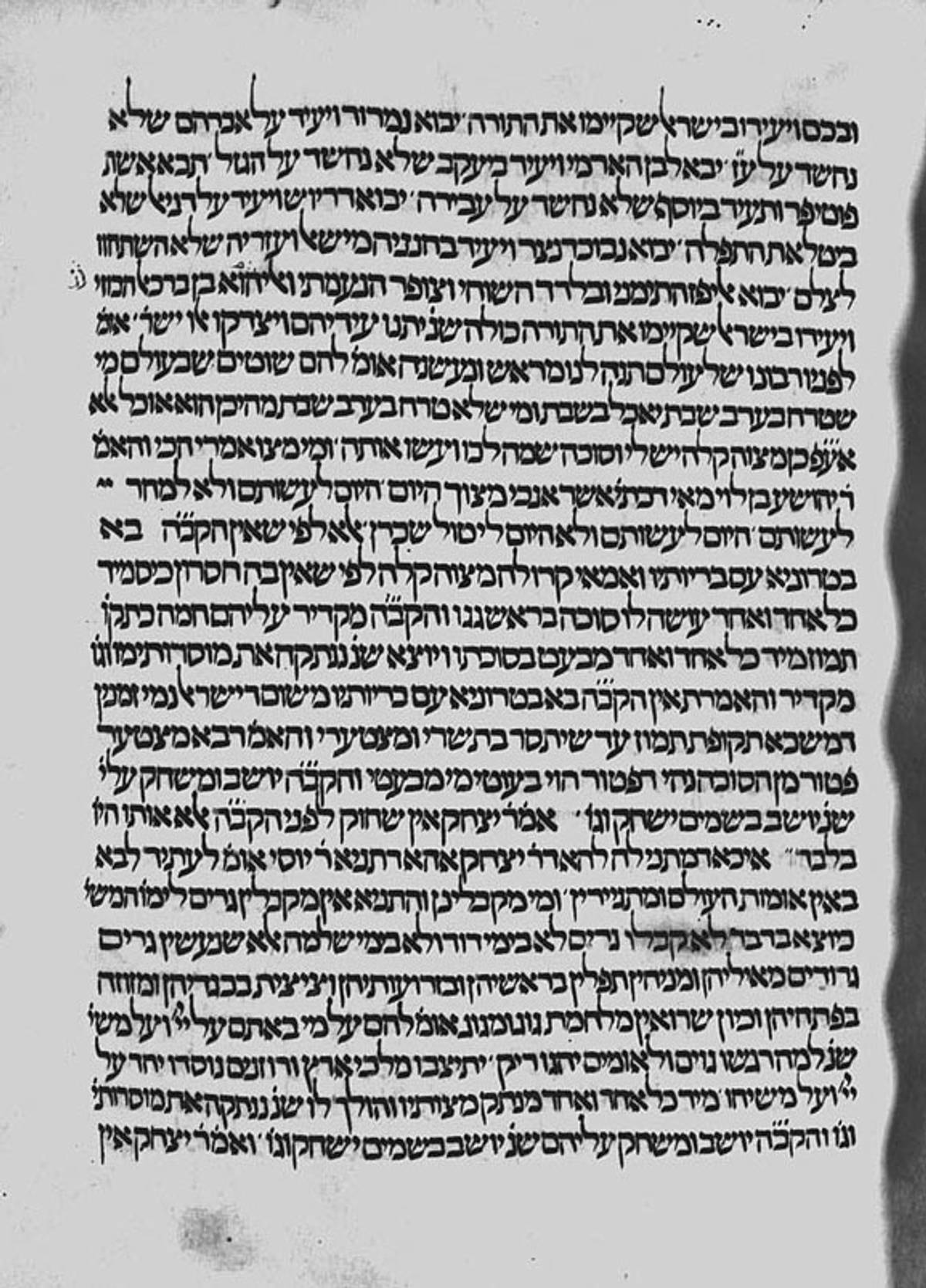

An excerpt from the author’s recent book, Time and Difference in Rabbinic Judaism.

God’s Time Since Creation

The tendency to juxtapose human and divine time underpins rabbinic accounts that imagine what God does with the seemingly infinite free time after the work of creation has been completed. Leviticus Rabbah portrays an exchange between Matrona and Rabbi Yose in which a skeptical Matrona tries to figure out what keeps God so busy during the many hours of each day:

Matrona asked Rabbi Yose ben Halafta, saying: For how many days did the Holy One, blessed be He, create His world? He said to her: For six days, as it says “For six days God created the heavens and earth …” (Exodus 31:17). She said to him: And since then [or: from that hour until now], what does God sit and do? He said to her: “He sits and creates matches, so-and-so’s daughter to so-and-so, so-and-so’s wife to so-and-so, so-and-so’s wealth to so-and-so.” She said to him: How many slaves and maidservants do I have, and easily within a single hour. I could match them up! He said to her: If it is easy in your eyes, it is as difficult for God as splitting the Sea of Reeds, as it says “God makes the solitary dwell in a house … ” (Psalms 68:7). Rabbi Yose ben Halafta went to his home. What did [Matrona] do? She sent for and brought a thousand slaves and a thousand maidservants and she stood them in rows. She said to them: so-and-so will go with so-and-so, and so-and-so will go with so-and-so. In the morning, they came to her, this one’s head disheveled (as in mourning), this one’s eyes blinded, this one’s arm broken, this one’s leg broken. One said: I do not want this one, and another said: I do not want this one. She sent for [the rabbi] and said: Good is your Torah, beautiful and praiseworthy. He said to her: I did not tell you this, rather I said that if it is simple in your eyes it is as difficult for God as the splitting of the Sea of Reeds, as it says, “God makes the solitary to dwell in a house, He brings out the prisoners into prosperity …” (Psalms 68:7)

After learning that God created the world in six days, Matrona wonders what God has been doing in all of the hours since the final day of creation. Rabbi Yose explains that God acts as a matchmaker, matching marriage partners based on family status, wealth, and other considerations, and making all sorts of other matches for the sake of social order. Matrona is dubious about God’s time management. She remarks: “How many slaves and maidservants do I have, and easily within a single hour I could match them up!” Matrona’s reference to hours at this point in the narrative indicates either a relatively short duration that is still long enough to complete a task (as it does in Rabban Gamliel’s declaration that he would not allow even a single hour to pass without declaring his devotion to God in m. Berakhot 2:5, discussed in the previous. chapter) or a seasonal hour, meaning a twelfth of the day. Either way, in her remark, Matrona equates the entirety of God’s time (all of the hours since the world’s creation, as Matrona states earlier in the story) to a single hour of her own time. To prove her case, Matrona matches up the many men and women she has enslaved with one another (the lightness with which Matrona treats the intimate needs of those she has enslaved in this narrative is troubling, and yet the power and status differential between the characters is central to the dynamics of this story). She does this task hastily, in the course of a short afternoon, perhaps even in a single hour as she had predicted and sends them off with their new partners for the evening. In the morning, all of the couples she had created return in a severe state of marital disharmony: bruised, unhappy, and traumatized.

The narrative describes God as spending all of divine time matchmaking in heaven. The narrative might function exegetically, picking up on Genesis 2:18–21, which explains God’s reasoning for creating Eve as a partner for Adam: “Then the Lord God said: ‘It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper as his partner … but for the man there was not found a helper as his partner. So the Lord God caused a deep sleep.’” All other creatures have pairs, God notes, and Adam should have one too. God as creator, that is, already functions as a matchmaker (and, indeed, matchmaking is God’s final act of creation), and so it makes sense, according to the midrash’s logic, that God continues in this role after the creation of the world. Other midrashim and targumim develop the theme of God as matchmaker more specifically. Genesis Rabbah 18:1, for instance, describes God adorning Eve as a bride before presenting her to Adam. Numerous sources depict God braiding the first woman’s hair on the sixth day of creation, before introducing her to Adam. In Genesis Rabbah 18:4, God’s creation of a first wife does not work out and thus God creates a second wife, Eve, in her place. These traditions emphasize that finding an appropriate spouse takes considerable amounts of time and effort and that God is committed to this task. In the rabbinic interpretation developed in the dialogue between Matrona and Rabbi Yose, God initiates the matching of pairs among animals and eventually between Adam and Eve during the week of creation (and specifically on the sixth day of creation). Thereafter, in the time following the world’s creation, God is imagined to continue this work of producing pairs by playing the permanent daily—even hourly—role of heavenly matchmaker for each and every human couple, and perhaps not only for humans but for all beings and things that require pairing. In the midrash, after all, God not only matches couples but is also responsible for other types of matches, ordering the entire cosmos and ensuring its equilibrium.

This story might also function polemically. The failed figure, Matrona, is an obvious foil to the wildly successful deity. This rabbinic dialogue could be engaging with ideas about creationism in Greco-Roman philosophical thought. Matrona, who represents the view that the world no longer requires a deity after the world’s initial creation, is controverted because her shortcomings as a matchmaker show that the universe cannot continue to exist in harmony without the direct, ongoing intervention of God during each hour of each day. The central debate here is one about the beginning of time and the eternity of the universe, and God’s place within it. From the perspective of this rabbinic story, God not only still exists actively in the world, God also exists within time, on a daily and hourly basis, and God is busy with the tasks involved in maintaining cosmic harmony. Indeed, the task at hand exemplifies God’s keeping order: God ordered the world during the process of creation, which entailed creating pairs of both animals and humans, and now God needs to keep it ordered by continuing the work of human matchmaking. It is an exact science, like telling exact time. It is also a way of perpetuating creation through the generation of generations, because couples are often assumed in rabbinic sources to have children (though this is an idealized view of the world, as in reality couples often cannot). Such matchmaking, that is, presents God as laboring in an unceasing hourly creation, necessary for the world to continue to exist.

There is an additional twist in this narrative. God’s time is spent creating the conditions for human relationships—marriage, business partnerships, and so on. This narrative is preceded by an exegesis of Proverbs 19:14, “Property and riches are bequeathed by fathers, but an efficient wife comes from the Lord.” This scriptural passage explains that wealth is inherited from one’s father but that a wife is provided by God. Thus, this passage provides a biblical underpinning for the portrayal of God as ultimately responsible for finding a good spouse. This exegetical context frames the story as one about God’s role in the marriage process as well as in the related process of wealth inheritance. Understood from this perspective, perhaps the story also engages with Christian privileging of abstinence and asceticism as the highest form of piety. In some contemporary Christian texts, the metaphorical system for describing the choice of an ascetic life is that of marriage: to be a virgin is not to remain unmarried but to be “married to Christ”; a virgin becomes Christ’s “bride”; and in some sources there is even mention of a wedding chamber. In his correspondence to the Emperor Constantius II in the mid-fourth century, the Patriarch Athanasius of Alexandria goes so far as to suggest not only that through a state of virginity Christians achieve angelic holiness on earth but also that attaining such stature proves the truth of Christian claims over those of Jews and heretics: “Accordingly such as have attained this virtue, the Catholic Church has been accustomed to call the brides of Christ. And the heathen who see them express their admiration of them as the temples of the Christ. For indeed this holy and heavenly profession is nowhere established, but only among us Christians, and it is a very strong argument that with us is to be found the genuine and true religion.” To be clear, marriage itself was not portrayed as illicit or negative by Paul, Clement, Athanasius, and others—such an attitude was vehemently opposed, for example, by the heresiologists, including Irenaeus, and used in polemics against Valentinians and other so-called “heretics.” Rather, virginity was a preferable choice that conferred elevated status. Here, this story might subtly argue against such a lifestyle, claiming that God not only condones marriage but that, indeed, all of God’s time is spent ensuring that marriages can continue in the most efficient and harmonious fashion possible. Regardless of the various possible apologetic or polemical undertones of the story (whether intended by the authors and tellers of this midrash or not), the narrative ultimately serves as a meditation on God’s devotion to the wellbeing and reproduction of humanity. Unlike Matrona, who allots virtually no time or effort to matching up couples for marriage, God is willing to spend all the time necessary—indeed, all the hours since creation—on an activity that is wholly directed at upgrading humanity’s quality of life.

This same ethos of divine care for humanity is conveyed in an alternative tradition about Matrona’s question, also preserved in Leviticus Rabbah. This second tradition records that Rabbi Yose ben Halafta did not tell Matrona that God spends all of God’s hours making matches but rather that, ever since the world’s creation, God “sits and makes ladders, by which He makes one go down and another go up.” Leviticus Rabbah explains that God is constantly elevating and downgrading people, probably in the context of judging them, as the midrash cites Psalm 75:8: “but it is God who executes judgment, putting down one and lifting up another.” In this image, God devotes all the hours of the day to bridging the spheres of heaven and earth not only through time but also through space. This midrashic tradition, too, might implicitly connect God’s time to the festival of Rosh Hashanah on which all human beings are judged.

God’s Daily Schedule

The idea that God spends all or a portion of the day making matches in heaven also appears in a number of interrelated ancient Jewish sources that present a detailed schedule of God’s entire day. The Palestinian targumic tradition on Deuteronomy 32:4 proposes that God spends a quarter of each day making matches in heaven. Deuteronomy 32:4 states: “The Rock, his work is perfect, and all his ways are just; a faithful God, without deceit, just and upright is he.” This biblical passage appears in a long chapter in the book of Deuteronomy devoted to “sin and punishment, divine favor and rejection, and … a description of certain qualities of God,” and the Aramaic translations of this biblical chapter exhibit sophisticated theological stances. In their reading of this particular passage, the targumim explicate what God’s “perfect” work entails on a daily—and even hourly—basis. The Fragment Targums, for example, explain that when Moses ascended Mount Sinai, he observed what God does each day: “Moses the prophet said: When I ascended the mountain [of Sinai], I saw there the Lord of all the world divide the day into four parts: three hours occupied with Torah, three hours occupied with judgment, three hours providing for all the world, and three hours matching men and women. Similar versions appear in Targum Pseudo-Jonathan and Targum Neofiti, which recount the same schedule but flip the order of the third and fourth quarters, so that God makes matches in the third quarter and sustains the world in the fourth. These varieties of God’s schedule are based on the division of the day into twelve hours. Each set of three hours is then considered its own unit of time, creating four distinct segments of the day, a common organization of time mentioned frequently in both rabbinic and Roman sources. In all of the targum versions that contain God’s schedule, God does the same set of four activities each day: God studies Torah, judges the world, makes matches, and provides sustenance or a livelihood for all of the world’s creations. The first activity communicates the importance of Torah study: it is such a crucial task that God prioritizes it, starting each day with three hours of learning. The subsequent three activities represent care for humanity: providing food or financial resources for them, ensuring that they have companionship, and judging them.

This tradition about God’s hourly schedule, preserved in the targumim, is related to the aforementioned tradition about Matrona questioning God’s schedule. Though the answers differ slightly—in the Matrona story God spends all hours of the day matchmaking and in the targumim God only spends three hours each day matchmaking—it is clear that they allude to an underlying idea that a significant amount of God’s time is occupied with pairing couples. In both traditions, God’s ongoing matchmaking is linked with God’s original pairing of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.

A late antique Palestinian Aramaic poem features the same divine schedule. The opening line of the poem refers to God as “Ancient of Days,” establishing God as one who has existed since the beginning of time. In the version of God’s schedule that the poem describes, wisdom pervades the way in which God uses time: “God divides the day / wisely into four parts / for three hours God touches [i.e., engages with] the Torah / that preceded all creation / which is wisdom / that was gifted to the nation.” The reference to wisdom, made several times throughout the poem, likely alludes to Proverbs 8, in which God’s companion Wisdom accompanies God during the period of the world’s creation. The poem then describes God’s three hours of judgment and three hours of providing sustenance to the inhabitants of the world, both of which are also described as being done “in wisdom.” The remaining focus of the poem, though, is on the time that God takes to pair up couples in marriage and the celebratory spirit with which God engages in this important task.

From the perspective of this rabbinic story, God not only still exists actively in the world, God also exists within time, on a daily and hourly basis, and God is busy with the tasks involved in maintaining cosmic harmony.

Though the purpose of the poem is unknown, it is reasonable to assume, as previous scholars have, based on its theme, style, tone, and rhetoric, that it could have been recited at a marriage celebration to commend a soon-to-be-wed or newlywed couple. The poem describes how God makes perfect matches and how for three hours each day God binds together grooms with brides and adorns them with wedding crowns. Just as God created the Torah before forming the rest of the world, so too God matches couples even before their births, when they are each in their mothers’ wombs. The poem then addresses the groom directly, explaining that God weighed the man and woman to make sure that they balance each other out, creating the pair as one would a set of harmonious balances and then presenting them to the congregation. The poem continues by wishing the couple a good life ahead, that peace should dwell between them, and other blessings for good fortune, a continuous supply of wine, and a dozen sons. The poem, though fragmentary, ends with a wish that the couple should mark the day with complete joy and imminent redemption, with all who have come to join them in celebration. This poem provides one example of a context in which the idea of God’s daily schedule was not only discussed exegetically or polemically but also adapted for use in a ritual or liturgical context, in this case a wedding celebration. The tradition that God spends hours each day matchmaking is evoked in this poem to argue that a divine bond links the celebrating couple to one another and that God will continue to watch over them in their subsequent life together. The couple is quite literally, the poem insists, a match made in heaven. This is a vivid example of the way in which God’s heavenly time was imagined to have directly impacted earthly marriage on a special occasion for celebration—a wedding day.

A modified version of God’s daily schedule appears in the opening pages of tractate Avodah Zarah in the Babylonian Talmud. Though this divine daily schedule is quite similar to the Palestinian traditions, it is embedded into a different literary context, appended to the end of a polemical story about all the nations of the world approaching God on the day of judgment at the end of time. The broader homily asserts Israel’s superiority over other peoples not only in the present world but also in the eschatological future. The narrative about God’s time reads as follows:

The day consists of twelve hours. During the first three [hours], the Holy One, blessed be He, sits and occupies Himself with the Torah. During the second three [hours], He sits and judges the whole world, and when He sees that the world is so guilty as to deserve destruction, He stands from the seat of Justice and sits on the seat of Mercy. During the third three [hours], He sits and feeds the whole world, from the horned buffalo to the brood of vermin. During the fourth [three hours], He sits and plays with Leviathan, as it says, “There is Leviathan, whom you formed to play there.”

In this text, God’s day is also subdivided into four three-hour segments, but some of God’s activities differ from the activities described in the targumim.

In both the Palestinian and the Babylonian texts, God spends the first quarter of the day studying Torah. God’s second task, judging the world, appears similar in the targumim and in the Babylonian Talmud. There is a key difference, however, inserted into the description of God’s judgment. In the targumic traditions, God simply “deals with justice” or “sits in judgment.” In the Babylonian Talmud, in contrast, God begins this segment of the day by sitting in the seat of judgment. The problem is that when God applies only strict justice to the world, the verdict is too harsh because, inevitably, humanity deserves to be completely eradicated (this sentiment resembles the gloomy ending to the Babylonian Talmud’s account of the final hours of the sixth day of creation). Upon realizing that the world would be destroyed if justice is the only value used to judge it, God stands up, gains perspective, and considers the world through the lens of mercy. God plays “musical chairs,” moving from the seat of justice and choosing the seat of mercy—a shift in perspective that allows the world to continue to exist. In the Babylonian Talmud, as in the targumim, God then spends three hours feeding the creatures of the earth. Perhaps the activity of feeding all of the world’s creations highlights God’s supreme power. Most significantly, however, whereas God creates matches between couples in all of the Palestinian targumic texts (sometimes in the third segment of the days, sometimes in the fourth) as well as in the Aramaic wedding poem, this dominant Palestinian motif is absent in the Babylonian Talmud’s narrative of God’s day. Instead, God spends three hours of each day laughing or playing with Leviathan. This last daily activity might relate to matchmaking more than appears at first glance.

Whereas the targumim anchor God’s schedule to their interpretation of Deuteronomy 32:4, the Babylonian Talmud relates its conceptualization of God’s time to a set of verses from Psalm 104. Psalm 104:26, about the creation of Leviathan and its playing in the sea, is explicitly cited as a proof text for the role of Leviathan in God’s day. A closer look at the text, however, suggests that the Psalm not only is evoked in relation to Leviathan but also offers a broader outline of God’s creation of the world and how God has been spending time since then. The text from Psalms reads:

He made the moon to mark the seasons; the sun knows its time for setting. You make darkness, and it is night, when all the animals of the forest come creeping out. The young lions roar for their prey, seeking their food from God. When the sun rises, they withdraw and lie down in their dens. People go out to their work and to their labor until evening. O Lord, how manifold are your works! In wisdom you have made them all; the earth is full of your creatures. Yonder is the sea, great and wide, creeping things innumerable are there, living things both small and great. There go the ships, and Leviathan that you formed to play in it. These all look to you to give them their food at their appropriate time [ותעב םלכא תתל]; when you give to them, they gather it up; when you open your hand, they are filled with good things. When you hide your face, they are dismayed; when you take away their breath, they die and return to their dust. When you send forth your spirit, they are created; and you renew the face of the ground.

This passage offers a biblical basis for what God does during each segment of the day: God feeds various animals, forms Leviathan to play in the waters, creates and takes away life. The text does not mention when God performs each activity, nor does it so neatly divide God’s activities into distinct categories. The specific timing of God’s acts, though, does have some basis in the proof text. The passage begins by referring to God’s creation of the heavenly bodies, which “mark the seasons” along with the cycle of days. Night and day are described with the hustle and bustle of animals and people. Food is distributed “at the appropriate time.” The narrative in the Babylonian Talmud assimilates these general time-related references, along with the activities the passage describes, into a daily schedule for the divine. Through a playful rereading of Psalm 104:26, in which Leviathan no longer frolics in the waters created by God but rather sports with God, the rabbinic passage also establishes Leviathan as a creature created specifically for divine play.

Why does God spend part of each day playing with Leviathan? Leviathan is associated in other ancient Jewish and rabbinic sources with the primordial past, the eschatological age, the World to Come, and the divine realm, and this narrative about God’s daily schedule is embedded within a longer homily about the eschatological age. This portion of God’s day thus connects divine activity both with the world’s creation (during which God created Leviathan, in some rabbinic traditions during the mysterious period of twilight in the transition between the sixth and seventh days, before the onset of the Sabbath when Israel is already required to cease from work but when God is permitted to continue the work of creation) and with the world’s eschatological end (during which Leviathan’s flesh serves as the main course of the eschatological heavenly banquet, and when Leviathan’s skin will become a sukkah, a protective hut, for Israel). God and Leviathan both find themselves in heaven during the period between the world’s creation and the eschatological age. They are the only two beings without partners, and so they fill their time by keeping each other company between the beginning and the end of time.

God’s playdate with Leviathan communicates God’s superiority over this creature, as Debra Scoggins Ballentine notes about other biblical, Second Temple, and rabbinic Leviathan traditions: “These narrative details contribute to the texts’ shared claim that Yahweh/Theos has universal dominion by implying the following: first, he is not threatened by any rival divine beings because he created everything, including Leviathan and Behemoth; and second, Yahweh/Theos has made preparations for the eschaton from the time of creation, which provides narrative proof that he controls the present.” Notwithstanding the assertion of God’s power over Leviathan, by evoking Psalm 104, which depicts Leviathan as a plaything, the rabbinic text also presents Leviathan as God’s partner. Job 40–41, too, presents Leviathan as a marvelous being created for God, interlacing the language of military conquest with that of romantic courting in its description of Leviathan (the word קחש, translated here as “to play,” can have sexual connotations, as in “to frolic”). In the mythological background of the ancient Near East, from which the Leviathan motif derives, epic sea battles often unfolded between partner-adversaries, those simultaneously coupled and warring. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Leviathan only appears in the Babylonian version of God’s daily schedule, perhaps signaling long-standing local Mesopotamian traditions. B. Baba Batra 74b preserves a tradition that God created two Leviathans, one male and one female, in language similar to the way in which God is said to create the first human as male and female:

All that the Holy One, blessed be He, created in His world He created male and female. Even Leviathan, He created male and female, and lest they mate with one another they would have destroyed the whole world. What did the Holy One, blessed be He, do? He castrated the male and killed the female, preserving it in salt for the righteous in the future.

In this passage, God destroys the female Leviathan and preserves her flesh in brine for the eschatological era, when Israel will feast on her body during the eschatological banquet. After God’s slaying of the female Leviathan, a single castrated male Leviathan remains in the world. This surviving Leviathan and God are left as the only unpartnered entities in the world; the image of the two sporting together conveys the latter’s dominance as well as enjoyment of the former’s company. Rather than arranging human partnering during this quarter of the day, as the Palestinian traditions suggest, here God partners in play with Leviathan. The rabbinic text in b. Avodah Zarah 3b holds these two dimensions of Leviathan’s identity—Leviathan as companion and as adversary— together in God’s daily encounter with it.

The passage immediately following the description of God’s daily playdate with Leviathan, however, has a rabbi objecting to the idea that God still plays or laughs with this creature. This rabbi recalls a competing rabbinic tradition that states that God has not laughed since the destruction of the temple: “Rav Aha said to Rav Nahman bar Isaac: Since the day of the destruction of the temple, there is no laughter for the Holy One, blessed be He.” The word used to connote laughter can mean both play and laughter, interrelated as they are. A slightly revised schedule is thus proposed to accommodate Rabbi Nahman bar Isaac’s objection. The text explains that since the temple’s destruction God spends the last quarter of each day instructing schoolchildren. This tradition is itself based on a passage from Isaiah 28:9 that depicts God teaching children weaned from their mothers’ milk. The talmudic text then asks who taught these children before the destruction of the temple and answers that either the angel Metatron did or, alternatively, God took care of this task even while the temple still stood, in addition to God’s other responsibilities. Whereas God plays and laughs with Leviathan before the fall of Jerusalem, God does not play and laugh with these children after the temple’s fall. Instead, God, in the role of a serious pedagogue, instructs them as their rabbi and teaches them as they grow.

God’s first activity of each day—the study of Torah—is absent from the Psalms passage, and it appears to be based on Palestinian rabbinic traditions unrelated to the biblical proof text (and is indeed found in targumic traditions). Foregrounding Torah study comes as no surprise in a rabbinic text: God begins the day participating in the activity rabbis most esteem, a reflection of their own values, which they project onto God. Immediately following this narrative, the pericope adds several passages praising those who devote their time to Torah study and outlining the punishment deserved by those who do not: “Anyone who ceases from [learning] words of the Torah and indulges in idle gossip will be fed glowing coals of juniper,” “Anyone who engages in Torah at night, the Holy One, blessed be He, extends a thread of grace to him during the day,” “Anyone who engages in the study of the Torah in this world, which resembles night, the Holy One, blessed be He, extends a thread of grace to him in the World to Come, which resembles the day.” A redactor might even have appended these passages here precisely because of their similar insistence that specific time each day be devoted to Torah study by those on earth just as it is by God in heaven.

Eliyahu Rabbah, a later rabbinic midrash probably compiled in the region of Palestine, combines God’s time during the creation of the world with the divine daily schedule thereafter. The midrash explains that God tells the People of Israel that God sat for 974 generations before the world’s creation, and during this long period of time God expounded all of the words of the entire Torah. God then explains that “since the day when I created the world and I sat myself down on my throne of glory, a third of the day I read and study; a third of the day I mete out judgment to the whole world; and a third of the day I do charity [הקדצ] and I feed and sustain the entire world and all that I created with my hands; and I only have a single hour of laughter [קוחש] each day!” Unlike God’s daily schedule in b. Avodah Zarah 3b, in this midrash, the divine day is divided into only three blocks of time. God engages in serious activities throughout the day and only manages a short time—an hour—at the end of the day for leisure. This midrash appears in a chapter devoted to the idea that a person should not waste too much time with קוחש; the midrash therefore expends much of its energy trying to define what קוחש entails. It offers different possibilities based on various biblical passages that use the terms קחש and קחצ: gossip, inappropriate sexual activity, idolatrous worship, foolishness. The verb קוחש is also the word used to describe God’s play or laughter with Leviathan for the last three hours of each day in b. Avodah Zarah 3b. In contrast to the tradition in the Babylonian Talmud, here God only laughs for a single hour (and the text does not specify that God spends that hour with Leviathan).

In this midrash, God’s schedule explicitly serves a pedagogical function, modeling for people how to spend their daily hours and warning them not to waste too much time on leisure or pleasurable activities that do not have a higher or deeper purpose. The midrash ends by recounting a conversation that transpires between God and each person who has reached the end of life. God approaches each person and asks: “my son, why did you not learn from your father in heaven, who sits on his throne of glory, a third of the day he reads and studies, a third of the day he metes out judgment to the whole world, and a third of the day he engages in charity … and he only has a single hour of laughter [קוחש] each day?” Everyone is held accountable, in this conversation, for having applied their Torah studies to their actions or having wasted too much time on nonsensical activities. God’s daily schedule, the midrash explicitly argues, should be emulated in human organization and use of daily time.

Other Divine Daily Activities

A number of other narratives in the Babylonian Talmud ascribe additional daily activities to God. In addition to the tradition that God spends a portion of each day playing or laughing with Leviathan, parallel passages found in b. Sanhedrin 105b, b. Berakhot 7a, and b. Avodah Zarah 4a explain that “God is angry every day.” This opinion is based on a biblical verse, Psalm 7:11, that mentions God’s daily fury: “God is a righteous judge, and a God who has indignation every day.” The rabbinic passage then inquires into the duration of God’s wrath and answers that it lasts for only a moment each day. B. Berakhot 7a and b. Avodah Zarah 4a both elaborate on this tradition by explaining that a moment (עגר) lasts for a tiny fraction of an hour—for example, “one fifty-eight thousand, eight hundred and eighty-eighth of an hour” or “one fifty-three thousand, eight hundred and forty-eighth of an hour.”10 B. Avodah Zarah 4b adds a second opinion about the length of a moment: “And how long does His wrath last? A moment. And how long is a moment? … As long as it takes to utter this word [that is, the word עגר]. And whence do we know that His wrath lasts a moment? As it is written, ‘For His anger lasts a moment, His favor lasts a lifetime (Psalm 30:6).’” Finally, the texts ask about the time of day when God is angry. The narratives explain that God is only angry “in the first three hours” of the day. B. Avodah Zarah 4b thus explains: “When is God wrathful? Abaye said: During the first three hours, when the comb of the cock is white. And is it not white at every hour? At all hours it has red streaks, but at that time there are none.” B. Berakhot 7a expounds similarly, that God is angry sometime during the first three hours of the day, when the sun whitens the crest of the rooster and it stands on one leg. When a possible objection is raised that a rooster stands on a single leg “every hour” of the day, the objection is likewise resolved by explaining that God is only angry when there are no red streaks on the rooster’s crest, which occurs only in the morning. In this set of traditions, the duration of God’s anger is incredibly short, and even though God’s wrath is predictable because it happens at the same time each day, its duration is so limited that humans cannot accurately anticipate when this anger will strike (that is, they have no control over God’s anger). Finally, b. Berakhot 7a provides an explanation for why God’s anger is a morning phenomenon: “At the hour when the sun shines, all of the kings of the east and the west put their crown on the ground and prostrate before the sun, immediately [God] grows angry.” According to this opinion, attributed to Rabbi Meir, God’s momentary daily fit of anger is caused by earthly kings who worship the sun as it rises early each morning. God, this tradition implies, throws a fleeting temper tantrum out of jealousy. God does so, moreover, at the very start of the day when the sun begins to rise—in fact, at precisely the time when one is permitted to begin reciting the morning Shema and morning prayers. The passage explains that God’s daily prayers assist God in overcoming anger toward Israel for their transgressions and finding the mercy with which to judge them. This set of traditions, which reappears in various contexts in the Babylonian Talmud, depicts God as experiencing strong daily emotions similar to a human being but also presents divine anger as predictable, brief, and temporary.

These passages about God’s anger also suggest that, despite God’s rigid schedule, God remains available to respond spontaneously and in the moment to human beings. While God directs divine fury at those who do not worship correctly, God also reacts in gentler ways to those God cherishes, especially rabbinic figures. A story found in b. Baba Metsia 59b, known as the “Oven of Akhnai,” narrates an extended debate between rabbis about an obscure purity regulation. At the end of the dramatic story—in which a tree moves, a river flows backward, a wall sways, a heavenly voice intervenes into the debate, and much interpersonal antics unfold—the Babylonian Talmud’s redactor adds a follow-up: “Years later, Rabbi Nathan encountered Elijah. He [Rabbi Nathan] asked him: What did God do at this hour [אתעש]? He [Elijah] answered: He smiled and said: My children have defeated me, my children have defeated me!” At the time when this rabbinic debate ensues, God observes them from the heavens and reacts emotionally to them—in this case smiling and muttering in approval. Even as other rabbinic passages put God on a rigid schedule, this and other narratives also suggest that God is always present, keeping track of the world’s inhabitants and their actions in real time, and able to intervene or comment at any hour of the day.

B. Berakhot 6a suggests that God also observes the paradigmatic positive time-bound commandment of wearing phylacteries every morning. By donning phylacteries, God marks the start of each day in the same way that rabbinic men who don phylacteries do. The parchment rolled into God’s phylacteries, however, does not contain words of divine praise (the Shema, Deuteronomy 6:4), as Israel’s do. They articulate, instead, God’s love of Israel by quoting 1 Chronicles 17:21, “Who is like your people Israel, one nation on the earth whom God went to redeem to be his people.” Through these matching biblical verses, the narrative explains that while Israel’s phylacteries express devotion to God, God’s phylacteries reply with enthusiastic affirmations of God’s devotion to Israel. This description of God’s morning ritual (the quintessential positive time-bound commandment), alongside God’s other daily activities, further cultivates a sense of divine-human reciprocity and focalizes God’s care for humans—and for Israel in particular. It also emphasizes, as so many sources do, that when God serves as an exemplar, it is primarily for rabbinic men, rather than for everyone.

Beyond the rabbinic corpus, God’s participation in thrice-daily prayers appears in the mystical text Hekhalot Rabbati, a source roughly contemporaneous with the composition of the Babylonian Talmud and from the same geographical region. In this text, God descends from the upper heaven to the seventh heaven three times each day as humans pray to God and as angels “recite hymns, play musical instruments, and dance.” Rather than receiving daily sacrifices in the temple, God accepts daily prayers as they are recited in heaven and on earth. Hekhalot Rabbati imagines God’s time to be synchronized with both angelic and human prayer times. But God also prioritizes human prayer over angelic prayer in the way that God structures the day. The text explains that “each day, when dawn appears, the ministering angels request to recite songs. At first they surround the throne of glory like mountains … the majestic King sits and blesses the Hayyot.” God blesses the heavenly beasts with these words: “May that hour when I created you be blessed, may the planet under which I formed you be exalted, may the light of that day in which you occurred to the thoughts of My heart, shine.” At first, it seems as though God begins the day—at the hour of dawn, as the text emphasizes—by praising the heavenly beings. But then the text takes a surprising turn. God asks the heavenly creatures to quiet down so that God can listen to the prayers of God’s children: “Be silent before Me, all creatures that I have made, that I may listen to the voice of the prayer of My children.” As Ithamar Gruenwald explains: “when the heavenly beings say their morning blessings, God asks them to be silent so as to enable Him to listen first to the prayers of His ‘sons,’ the People of Israel.” God listens first to humans praying and then pays attention to angelic prayer.

God’s Nightlife

Whereas God’s daily schedule accentuates God’s connection to and care of the world and its inhabitants, God’s nightly schedule more emphatically underscores divine difference, for, according to most sources, only created beings need sleep, whereas God does not—and therefore God needs to both stay busy and mark time in the heavens during the night (killing and keeping time, as it were) while those on earth get their rest.

After describing God’s daily schedule, the narrative in b. Avodah Zarah 3b turns to God’s nightlife and offers a few alternatives for how God spends the evening hours.

And at night, what does He do? If you like you may say, the kind of thing He does by day. Or if you like you may say that He rides a light cherub and floats and passes in the eighteen thousand worlds He created, as is written, “The chariots of God are myriads …” (Psalm 68:18) … Or if you like you may say that He sits and listens to singing from the mouths of the Hayyot, as is written, “By day the Lord will command His loving kindness and at night a song shall be with me” (Psalm 42:9).

This passage is remarkably different in tone from the description of God’s daytime that immediately precedes it in the text, for whereas the text presents with certainty God’s daily schedule, it leaves ambiguous God’s night by using more tentative language: God either travels through the heavens with a company of angels, enjoys a heavenly concert, or simply performs the same daytime tasks in an infinite loop. Such tentativeness adds an element of mystery about God’s whereabouts and activities during the darkened hours. There are aspects of God’s time, this passage implies, that remain unknown. Moreover, it places the angels, liminal beings, in the liminal time of night.

In antiquity and the medieval period, nighttime was not reserved exclusively for sleep. Nocturnal activities, especially prayer, worship, study, meditation, and reflection, were common, both because stars and planets made for an awe-inspiring celestial scene and because of the nighttime’s silence. Jeremy Penner, in an article about nighttime worship at Qumran, writes that in a world without inexpensive artificial lighting, “the experiences with day and night stood in much greater contrast, as did the differences in the rhythms of work and sleep and the types of activities associated with daytime and nighttime … Night was … a significant period of time for the religious person … Human sleeping patterns helped foster an active nocturnal culture nighttime was not just a hiatus from daily life, but rather an important part of it.” Sleeping patterns, as natural as they seem today, are culturally specific; in many ancient societies, nighttime sleep occurred in two periods, the first at the beginning of the evening (first sleep) and then later before the morning hours (second sleep). In between, there was a period of time during which certain activities were performed. Whatever the specific rhythms of the night during this historical period and region and within rabbinic communities, God’s active nightlife seems to have been imagined as corresponding to the kinds of practices associated with the darkened hours across the ancient Mediterranean world, including the connection between the night’s starry sky and the heavenly angels in God’s retinue. Additionally, the idea that God spends the nights singing and worshipping with the angels in the heavenly realm in “eighteen thousand worlds” resonates with other texts as well, including those in mystical traditions discussed earlier. They imagine God to reserve the evenings for the angels, leaving a free schedule with which to engage with humans during the day when they are awake.

Sarit Kattan Gribetz is an associate professor in the Theology Department at Fordham University