The Hasidic Rebbe Who Helped Defeat Napoleon

Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi stood up to the secular French revolutionary, lighting a flame of resistance that still burns today

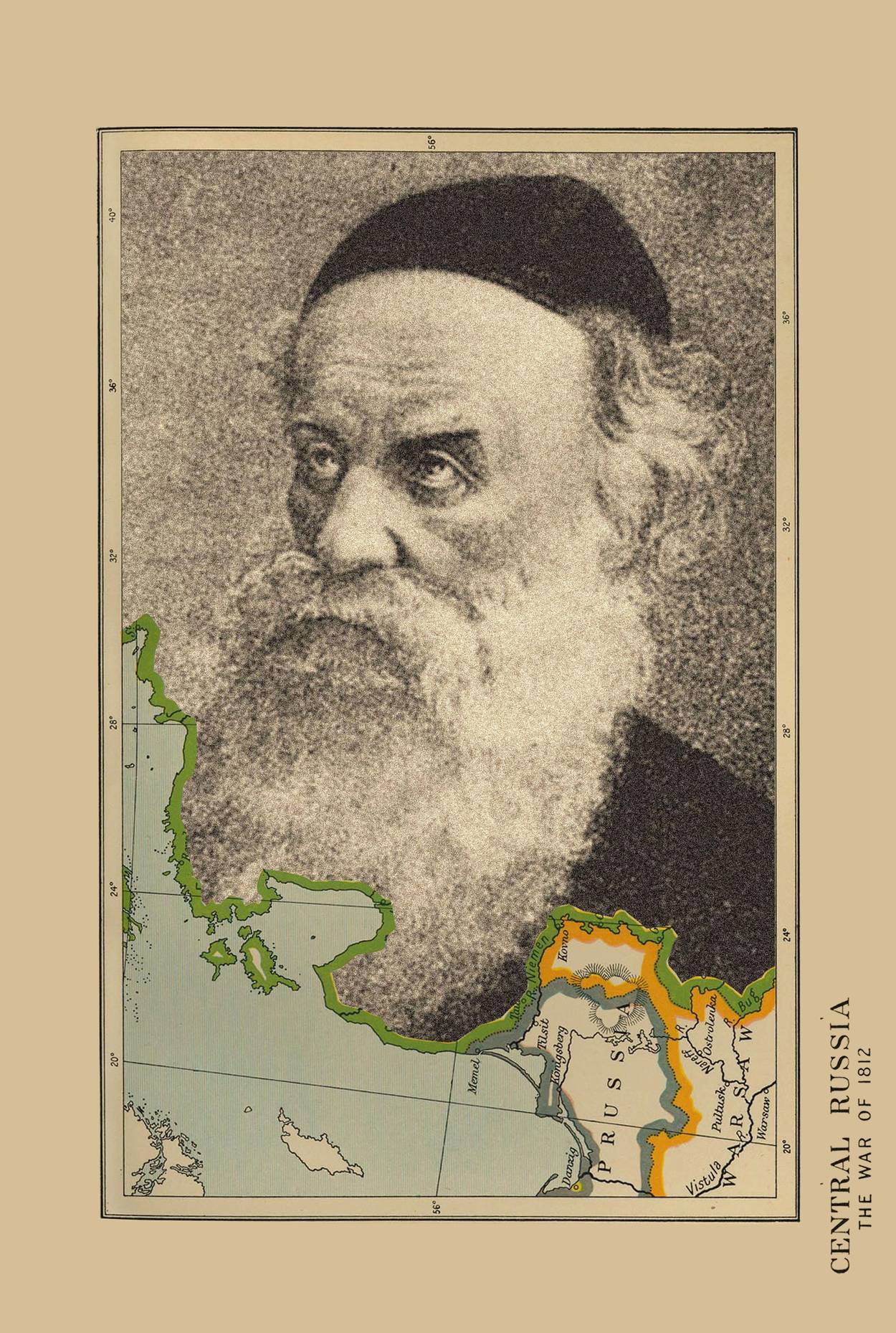

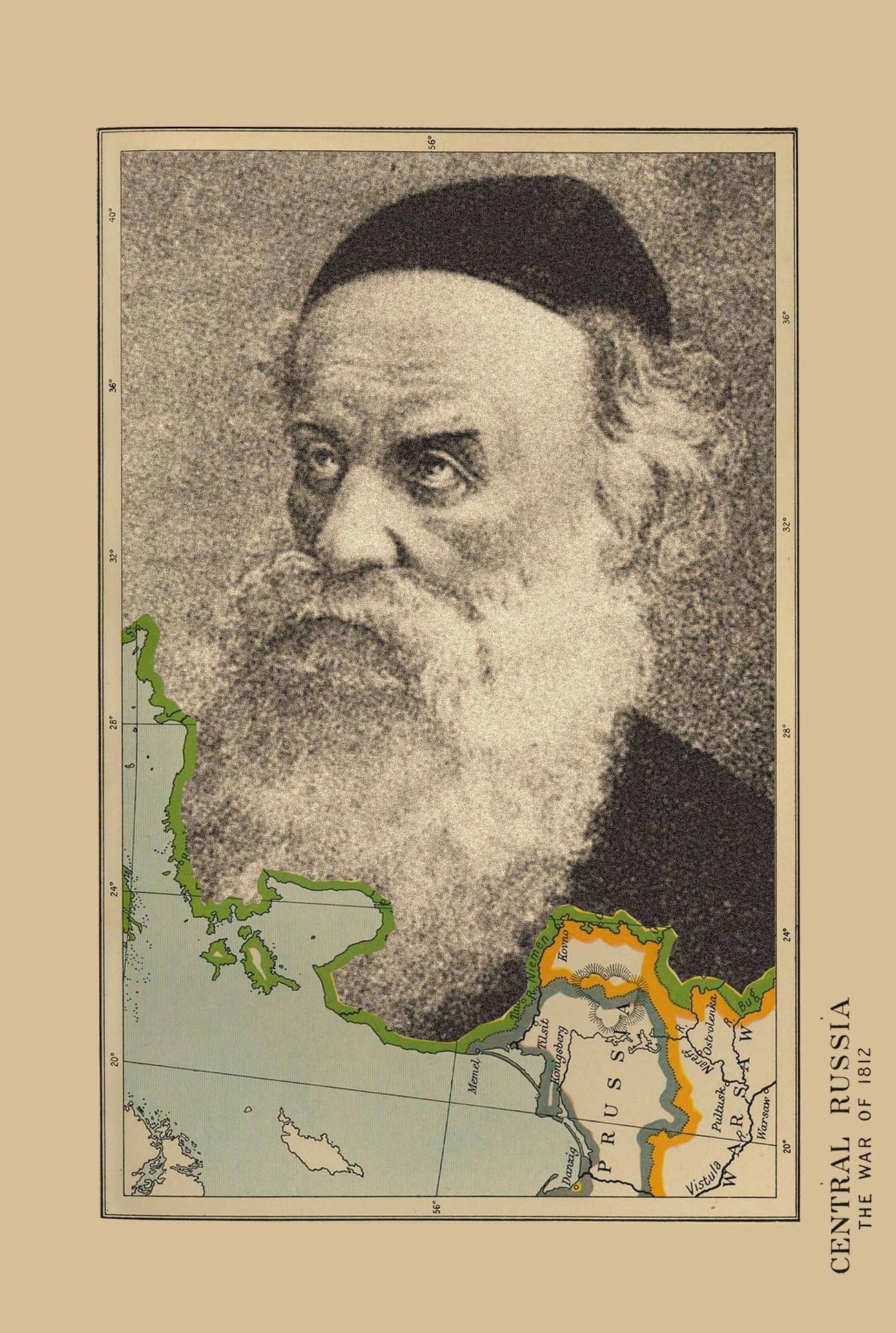

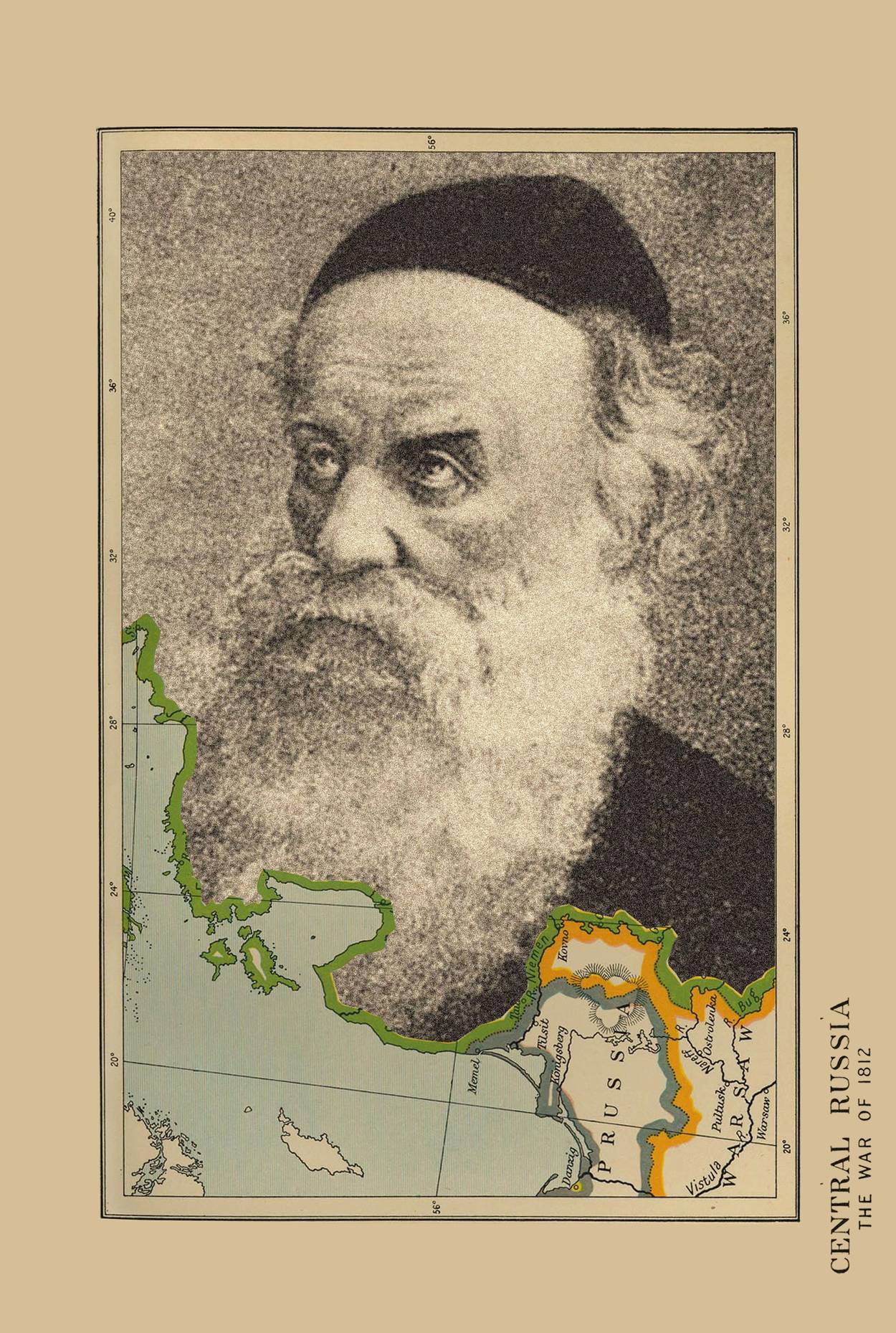

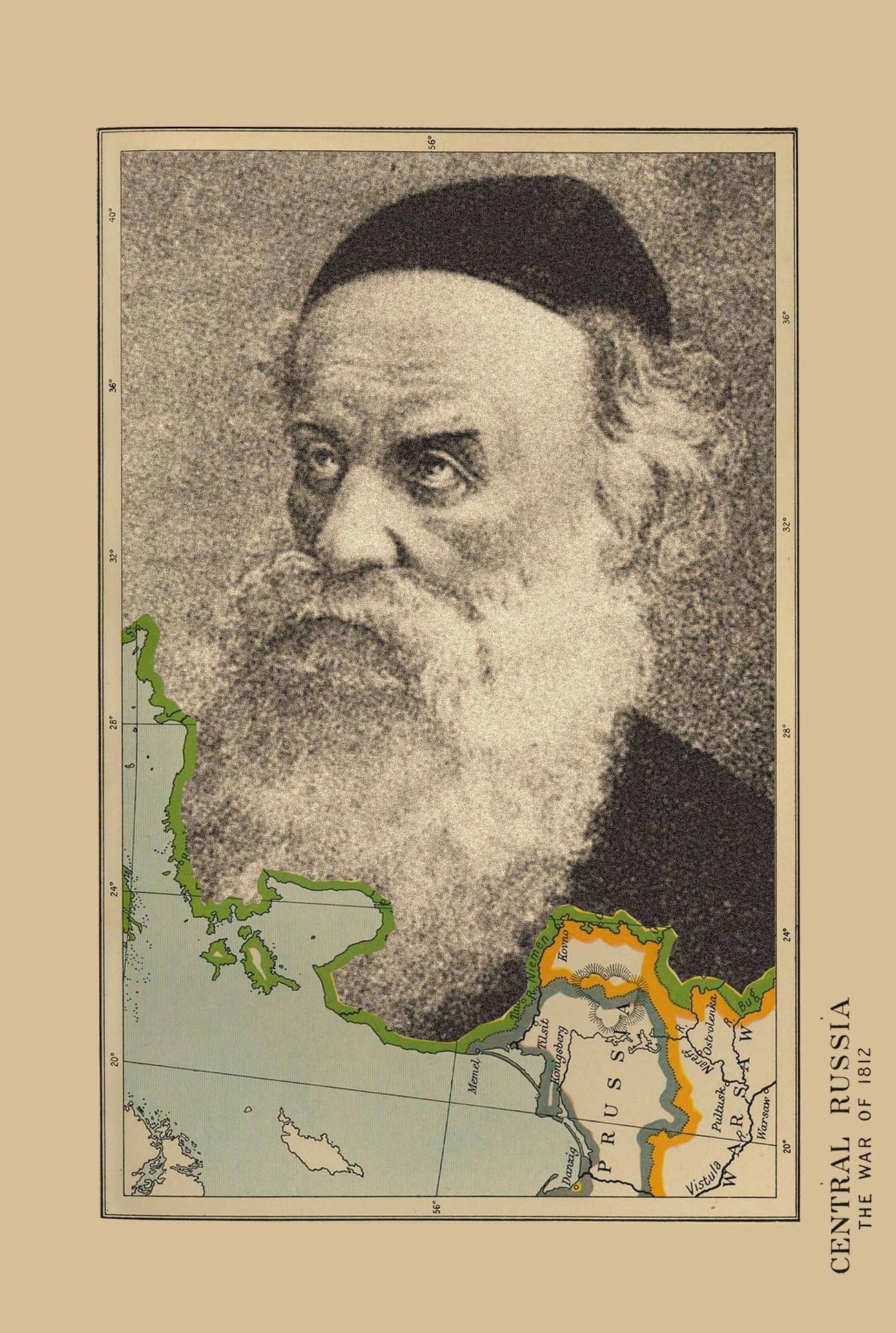

The old, sloping Jewish cemetery in Haditch, Ukraine, is one of those rare windows into the past. Look out from the hilltop, as I did recently, and a vista nearly unchanged in two centuries opens up below. During the winter you’ll see a frozen, grassy clearing dotted with barren birch trees descending to the banks of the placid Psel River. There, at the bottom and to the right, sits the original red brick mausoleum of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812), the Alter Rebbe.

The founder of the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement, Rabbi Schneur Zalman lived and taught in White Russia all his life. How he came to rest in central Ukraine’s Poltava region, 600 kilometers south of Liadi, is part of the dramatic tale of the Hasidic master’s last journey in this world. It is also the story of a Jewish leader who, during the great and terrible year of 1812 confronted and ultimately helped to destroy Napoleon Bonaparte, the emperor of the French and torchbearer of the Revolution, changing the trajectory of Jewish history and with it the world.

Rabbi Schneur Zalman was born in 1745 in the White Russian town of Liozna. As a young married man, he traveled to the Volhynian town of Mezritch where he first met the Baal Shem Tov’s successor, Rabbi Dovber, the great Maggid of Mezritch, becoming one of his leading students. In the aftermath of the Maggid’s death in 1772, his students divided Eastern Europe into spheres within which each one would continue the work of spreading the Baal Shem Tov’s message.

Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s territory was Lithuania, White Russia, and eastern Ukraine. It was here that, expounding upon the core ideas of the Baal Shem Tov and the Maggid, he developed a comprehensive intellectual framework for exploring the unity of God as it manifests itself in the world and man. It was among the Jews of this vast territory that his vision of the “mind’s dominion over the heart” first gained hold, and among them and their descendants that he came to be known simply as the Alter Rebbe, the Old Rebbe.

By 1812, the eve of Napoleon’s world-historic invasion of Russia, the Alter Rebbe’s name as a mystic and Halachic authority was well known. Just 14 years earlier he had been imprisoned on false treason charges in St. Petersburg, and his subsequent vindication and release by Czar Pavel on the 19th of Kislev was celebrated far and wide.

Despite his own suffering at the hands of the Russian Empire, when the emperor’s eastward designs became clear that summer, the Alter Rebbe announced his unconditional opposition to Napoleon. He was, writes biographer Andrew Roberts, “the Enlightenment on horseback.” He was the apex of the French Revolution, heralding the dawn of modernity and rule by, in the words of French historian François Furet, “the force of ideology and … the militants who embodied it.” Far more than simply a reflection of Russian Jewry’s broader loyalty to the czarist order, the Alter Rebbe saw in Napoleon an unprecedented threat to God’s world.

The Alter Rebbe’s son and successor as Lubavitcher rebbe, Rabbi Dovber Schneuri, penned a vivid description of the fateful summer, fall and winter of 1812 and his father’s opposition to Napoleon:

“As soon as the enemy, the notorious oppressor and wholesale murderer [Napoleon], entered the borders of Poland, into Kovno and Vilna, etc., [my father] began to deliberate with us about fleeing into the interior of Russia … ,” he wrote. If Napoleon were not arrogant, the Alter Rebbe observed, he would remain in Poland and fortify himself; persistence in his foolish belief in the military prowess vested in his own self, would be the root of his ultimate downfall. “At any rate,” the Alter Rebbe declared, “it is a great distress for the Jews, for not one will remain [steadfast] in his Judaism, nor retain his possessions.”

The Alter Rebbe’s stark rejection of Napoleon was on the surface not an easy or obvious position to take. It placed him in direct opposition to other great contemporary Polish and Galician Hasidic leaders, including Rabbi Yisroel Hopstein, the Maggid of Kozhnitz, and Rabbi Mendel of Riminov, who insisted that the liberation promised by Napoleon would be preferable to Russia’s oppression of its Jews. After all, “[i]t was the ideology of the French Revolution, incarnated in Napoleon, that liberated European Jewry from confinement in the ghetto,” as Irving Kristol observed in a 1988 Commentary essay.

Napoleon saw himself as nothing less than the secular Messiah. “I am called to change the face of the world; at least I believe so,” he wrote to his brother. “If I ruled a people of Jews, I would rebuild the Temple of Solomon!” he remarked another time. But Napoleon believed in nothing other than power and himself. “Were I obliged to have a religion,” the French emperor once said, “I would worship the sun—the source of all life—the real god of the earth.”

This was something the Alter Rebbe could not abide. True, millions would be emancipated, Jews among them—at least for a time—but at what price? For the Alter Rebbe, a devoted lover of his people, there could be no excuse to support a man, and through him a Revolution, whose legitimacy and powerbase was rooted in a denial of the divine. An ideology that denied the very existence of one God threatened nothing less than the destruction of who the Jews were in their essence, and thus the destruction, God forbid, of the Jewish people.

On one level, the Alter Rebbe’s argument with his Hasidic opponents was a simple one. While the material condition of the Jews might improve under the freedom promised by Napoleon, their spiritual circumstances would certainly falter. The Kozhnitzer Maggid and Rabbi Mendel of Riminov felt this risk was worth taking; the Alter Rebbe did not. On another level, however, the Alter Rebbe saw this as an existential battle to save the Jewish people, spiritually and materially.

On June 24, 1812, Napoleon tempted history by invading the Russian Empire, an endeavor no military commander had ever emerged from successfully. The Grande Armée’s advance cut straight through the heavily Jewish White Russian region that the Alter Rebbe called home. The Alter Rebbe vowed he would not live under the emperor’s rule for a moment, and on Friday, Aug. 7, he fled Liadi with his family and a circle of followers. Before leaving, he instructed that his remaining belongings be burned so as not to fall into Napoleon’s possession.

As the late Rabbi Yehoshua Mondshine has carefully documented in his The Last Journey (Ha’Maasa HaAcharon), the Alter Rebbe’s party was met by the Russian Army 20 kilometers east, at Krasny, where General Dmitry Neverovski was engaging in a heated rearguard action with the advancing French Grande Armée. Neverovski immediately issued documents granting the party right of passage and commanding soldiers and authorities to aid them. These documents survive until today, and allowed Mondshine to reconstruct the Alter Rebbe’s journey in meticulous detail. At many of the places along the Alter Rebbe’s route, he and his party left mere hours before the arrival of Napoleon and his advancing vanguard.

Throughout the next five months of arduous wandering—along a circular route that took him more than 1,500 kilometers through Smolensk, Moscow, Vladimir, Tambov, Orel, and then down to the tiny village of Piena, in Kursk province—the Alter Rebbe did all within his power to defeat Napoleon. He instructed his followers, among them the influential polyglot Moshe Meisels of Vilna, to spy on the French High Command on Russia’s behalf. When Napoleon’s armies entered the region he sent more emissaries to spy on their positions and report back to the Russians. Predicting that Napoleon would be forced to turn back and would wreak carnage on the Jewish villages sitting in the path of his eventual retreat, he worked to set up emergency housing for White Russian Jewry in Ukraine’s Poltava region.

As the war was being waged all around him, the Alter Rebbe spent what would be the final year of his life writing and reciting Hasidic discourses, many of them crystalizing core concepts of his revolutionary teachings. As the scholar Rabbi Dovid Olidort pointed out in a 2006 article in the Hasidic journal Heichal HaBaal Shem Tov, the Alter Rebbe’s foundational discourse of Adam Ki Yakriv (“When a man from [among] you brings a sacrifice”) printed in Likutei Torah (Zhitomir, 1848), in which he articulates the uniquely Chabad approach demanding the toil of personal development and negating the spiritual inspiration driven by proximity to the Tzaddik or witnessing a miracle, was taught in the spring of 1812. Moreover, Epistle Twenty in Tanya (Ihu Vichayohi Chad, or “He and His Emanations are One”), in which the Alter Rebbe explains fundamentals of Chabad thought such as the ascendency of concrete performance of mitzvot over actionless contemplation, was written just days before his passing.

Another of that year’s discourses offers an even more concrete window into the Alter Rebbe’s vehement hostility to Napoleon. In it, the Alter Rebbe delves into the lowliest expression of evil represented by the figure of Sennacherib, the king of Assyria and banisher of the 10 tribes of Israel. Unlike the other idolatrous kings of his time, who recognized the idea of a God of gods, Sennacherib rejected the very existence of a Creator. The Alter Rebbe alludes to the tradition that the Baal Shem Tov refused to travel in a wagon driven by a gentile who did not make the sign of the cross while passing a church along the road: “There is more repair for a non-Jewish believer than for a heretic,” the Alter Rebbe explained in the discourse. And so the lines were drawn: On one hand, there was Czar Alexander’s religious faith in the one Master of the Universe who created and controls the world, and on the other hand was Napoleon’s egocentric and heretical belief in his own divinity.

The Alter Rebbe was 67 years old in December of 1812. He was physically frail and the months on the frozen roads had taken a heavy toll on him. In the leadup to the preceding Rosh Hashanah, the Alter Rebbe was despondent when it became clear Napoleon would soon capture Moscow. The morning of the Jewish New Year saw the bloody Battle of Borodino, the only significant engagement between the two armies of the entire war. By day’s end the path to Moscow was open to the French, but that morning the Alter Rebbe’s mood had suddenly lifted. “I saw in my prayer that good change has occurred to our benefit, and our side will be victorious,” his son would recount him as saying. “Also [I saw] that they will take Moscow, but they will not have permanence, and salvation shall stand by us ...’”

Ultimately, Napoleon reached Moscow before being forced to turn back. The historian Andrew Roberts estimates that the emperor invaded Russia with 615,000 soldiers, losing 524,000. The Russian czar recognized his victory as nothing short of a miracle.

“Almighty God has granted us a striking victory over the famous Napoleon,” Alexander would tell his adviser Prince Alexander Golitsyn after witnessing the emperor’s disastrous escape over the Berezina river. Later, on his 1813 return to St. Petersburg, the czar would refuse the title “Alexander the Blessed.” “He attributed everything, the victory, to the Lord,” Golitsyn observed.

Though Napoleon would remain in power for another year and a half, the Russia campaign was his death knell. “The spell is broken,” Alexander observed.

For the Alter Rebbe, a devoted lover of his people, there could be no excuse to support a man, and through him a Revolution, whose legitimacy and powerbase was rooted in a denial of the divine.

By this time the Alter Rebbe was gravely ill. At the end of December, his party arrived in the tiny Russian village of Piena, where for five days the Alter Rebbe remained in a Russian peasant’s simple wooden hut. There, at the conclusion of Shabbat on the eve of the 24th day of Tevet, Dec. 27, 1812, he returned his soul to his Maker.

In all accounts of the Alter Rebbe’s last months it seems clear he intended Haditch as his next destination, either in life or death. Two hundred kilometers southeast of Piena, it was the site of the closest Jewish cemetery. Just three or four people accompanied the deceased rebbe on the dangerous wartime journey through unfriendly territory, traveling by sled to reach Haditch for the final interment.

“The [Jewish] cemetery there is on state lands, in a small wood along the Psel River …,” wrote Rabbi Dovber. “We built a nice wooden dome [over the grave], and also a large house [adjacent], and have prepared bricks for a permanent structure in his honor, as in the case of our righteous forefathers in the land of Israel, where people came to pray in times of distress …”

It was Rabbi Dovber who established the customs to be observed at his father’s resting place—removing one’s shoes and knocking three times before entering, reciting a special text called Maaneh Lashon, among other practices—all of which are adhered to at Haditch and the graves of the Alter Rebbe’s successors ever since. Curiously, he also instituted that a ner tamid, or eternal light, be placed in the burial chamber, an element unique to Haditch. Per Rabbi Dovber’s instructions, this lamp was to be fueled with pure olive oil, an expensive commodity in 19th-century Russia.

In an 1815 letter, Rabbi Dovber requests his followers contribute a small yearly amount for the purchase of olive oil to keep this lamp burning at all times. Despite apparent short lapses in its upkeep, even at the height of the bloody Russian Civil War it continued to burn. “We entered the mausoleum and felt an exalted awe there … [and prayed] for all Jews who found themselves in danger,” wrote Yehuda Chitrik, a yeshivah student who traveled there by freight train in the winter of 1920. The father and son who watched over the grave, Chitrik noted, guarded the eternal flame as well.

Napoleon was exiled to a dank home on a desolate rock in the South Atlantic, where, stripped of power and hope, he swiftly disintegrated. He died there on May 5, 1821. Meanwhile, 9,000 kilometers away, a lamp burned in a red-brick mausoleum in Ukraine.

Among those whose imagination was captured by the image of this everlasting flame aglow in the Alter Rebbe’s silent mausoleum was Zvi Preigerzon, a Hebrew writer in the Soviet Union. With both religious and secular Hebrew literature suppressed in the USSR, Preigerzon’s only work to appear during his lifetime was Aish HaTamid, or The Eternal Flame, smuggled out of the Soviet Union in 1966 and published in Israel under the pseudonym A. Tsfoni (Preigerzon’s book was released for the first time in English in 2020 by Academic Studies Press under his intended title, When the Menorah Fades). “Through summer and winter, day and night, for over a century and a quarter that menorah gave light without pause,” the Soviet Jewish writer recounts. “Its modest glow illuminated a little pocket of the world, and it was in that little pocket that the soul of numerous generations of Jews had vibrated, from the time of Napoleon on down ….”

Set just before and during the Holocaust that would consume the lives of Haditch’s Jewish inhabitants, the book made waves in Israel. “Of particular amazement was that in a country from which Hebrew had been ostracized for decades, an epic panoramic work had been written in rich Hebrew, constructed by a skillful hand, containing a colorful gallery of multidimensional characters,” the historian Yehoshua Gilboa recalled.

While Preigerzon’s book is very obviously fiction, telling the tale of characters who may or may have not existed, and recounting legends that most certainly did not, his descriptions of the place as he must have seen it during the summers he spent in Haditch in the late 1930s ring true. Though Preigerzon avoids discussion of the NKVD’s constant monitoring of the comings and goings at the Alter Rebbe’s grave, and does not mention Stalin’s Great Terror at all, he describes the deathly silence in the Soviet-era shtiebel, with prayer and holy books formerly belonging to the Jewish community scattered throughout the room and rolls of Torah scrolls lying in heaps on a long bench. He also tells of the attendant, a man whom he calls Ginsburg, sitting at a table and studying Tanya. “I haven’t yet liberated myself from the hands of the Sitra Achara,” Ginsburg tells Preigerzon’s protagonist, using the Kabbalah’s antonymic term for the force of impurity. And then Preigerzon comes to the book’s eponymous lamp, a symbol for what he calls “the very heart and soul of the Nation.”

Before the 1917 Russian Revolution petitioners had freely flocked to Haditch. Yet even after the Bolsheviks took power, the attendant, Yosef Gansburg—upon whom Preigerzon’s Ginsburg is fancifully based—continued caring for the grave and delivering written supplications he received from throughout Stalinist Russia. Even as every vestige of Jewish life and learning was suffocated by the Communists, the Alter Rebbe’s gravesite continued to inspire.

“Quite a few generations ago our forefathers built that [mausoleum] and lit the menorah over the holy grave,” Preigerzon’s protagonist observes as he stares down the hill at the Jewish cemetery. “Some sort of great hidden secret seems to hover in the air around the distant house.”

The red brick structure of the mausoleum (but not the shtiebel that stood adjacent) somehow survived the Nazi onslaught during the Holocaust as well as the malicious neglect of 70 years of Soviet rule. First restored in the 1980s, it has been updated multiple times since. Today, a modern visitors’ center and synagogue sits at the top of the hill, while the mausoleum and reconstructed shtiebel at the bottom are constantly maintained. Yet some things remain unchanged. Follow the long path down the hill, through the shtiebel and into the holy burial chamber itself, and you’ll see it. On the wall, directly across from the faded tombstone proclaiming this to be the earthly resting place of “the great and divine rav … our master and teacher Schneur Zalman, the son of Baruch,” hangs a huge glass cup filled with olive oil.

Its everlasting flame burns yet.

Dovid Margolin is an associate editor at Chabad.org, where he writes on Jewish life with a particular interest in Russian Jewish history. His work has appeared in The Weekly Standard and Mosaic.