Inventing the Karaites

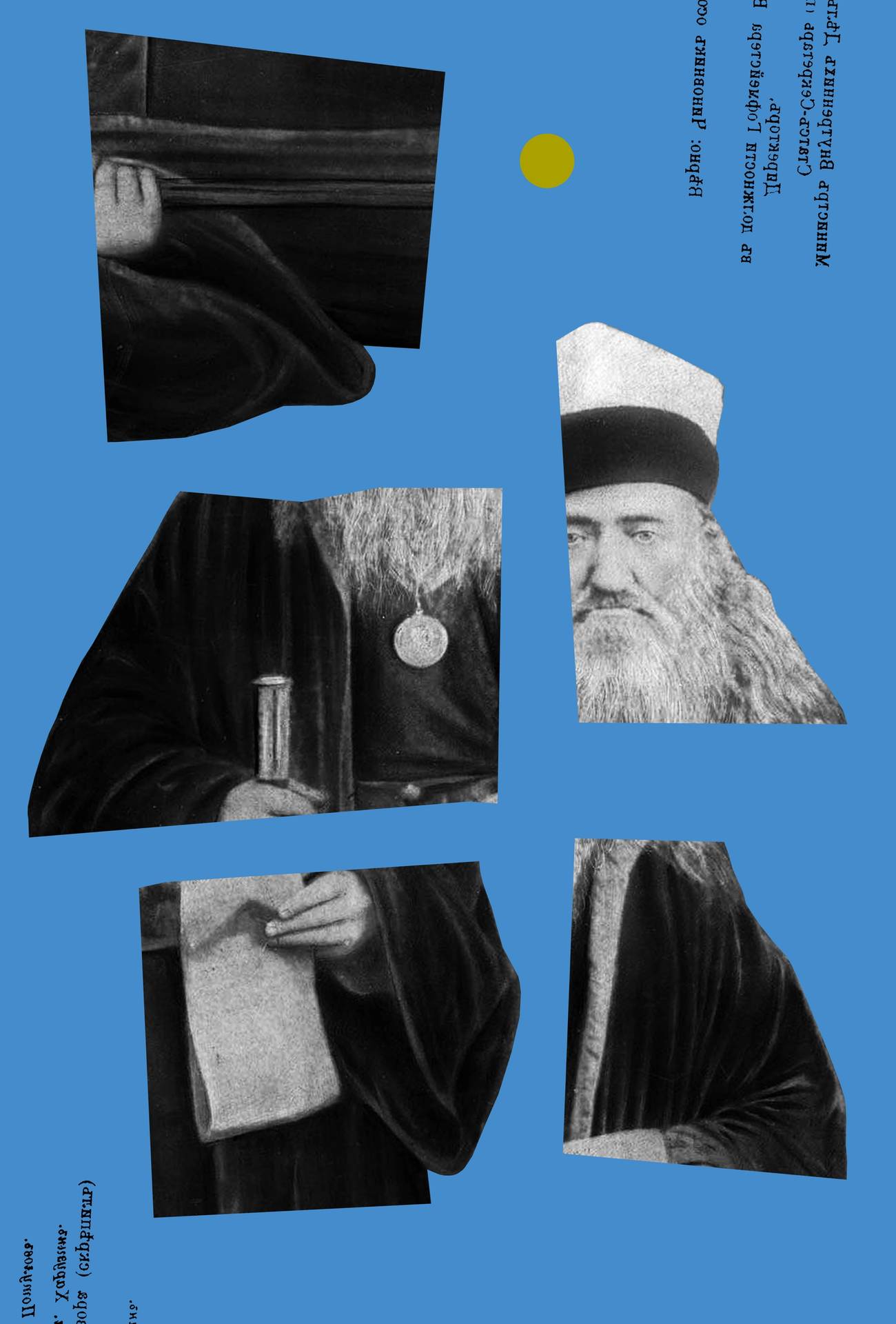

In the first installment of a two-part column, our ‘History Detective’ columnist begins tracing the story of Abraham Firkovich, the most prolific Jewish forger of all time

The world’s biggest collections of Jewish and Samaritan manuscripts are kept in Sankt-Petersburg, the former Russian capital sometimes known in the West as Saint-Petersburg, which has also been known as Petrograd (since WWI) and Leningrad (after Lenin’s death). They are lodged in what used to be the Imperial Public Library, which is now known as the Russian National Library, named after Saltykov-Shchedrin (a very high Imperial official and hysterically funny author). There are three Jewish and Samaritan collections located there: the First Firkovich Collection, the Samaritan Collection of Firkovich, and the Second Firkovich Collection.

The First Collection was acquired by Czar Alexander II in 1862 for a scandalously high price from Abraham Firkovich and his son-in-law, Gabriel, whose second name was Firkovich as well (both men were very distant relatives), though nobody called it “the First Collection” back in 1862.

The time was that of the “Great Reforms” in the Russian Empire. Slavery (sometimes translated as “serfdom”, but this European term was non-adequate) of the Russian peasantry was abolished in 1861, and 23 million former slaves were set free. Slaves in Alabama and Atlanta, Georgia, had to wait until the next year, and Jewish slaves in Tiflis (Tbilisi), Georgia, then part of the Russian Empire, had to wait until 1864-67.

Censorship on books was lightened, jury courts were set, the special Jewish draft (“Cantonists”) was abolished, glasnost was introduced (Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost of the 1980s was a homage to that 19th-century glasnost), and the status of Jews improved drastically. There was talk of total equality of rights of the Jews in Russia; Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky published their famous novels in the span of a couple of years. The economy boomed, with railways built everywhere by everyone at once. Abraham and Gabriel Firkovich invested almost all the incredibly high sum they got for their Hebrew manuscripts in the railway speculations and lost all the money. That was the background for building two more collections—the Samaritan Collection and the Second Firkovich Collection. Beyond many other motives, Abraham Firkovich was in desperate need of a new fortune.

Abraham Firkovich was born a subject of the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1787 in Łuck (Lutsk or Lutzk in Volhynia), and this is why I prefer the Polish spelling (Firkowicz) of his name. The town of his birth was once a capital to a European empire, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the local folks used to talk of ancient treasures hidden in the castle or in caves in the surrounding woods. It was home to Ashkenazi Yiddish-speaking Jews, Polish Catholics, Greek Orthodox “Russians” (now they are called Ukrainians), and a tiny Turkic-speaking community of Jewish religious dissidents, the Karaites. Abraham was a Karaite and lived in a double ghetto—a Jew among Gentiles, a “sectarian” speaking a strange tongue with an Oriental twist among other Jews. The family “exercized the craft of vodka artisanship,” to quote from an official document.

Firkowicz was, to a large degree, a medieval character. Born in an independent Poland-Lithuania, in the period of the early Jewish Enlightenment and of the persecution of the Hasidim by misnaggedim, he was witness to major transitions affecting the Jews. He lived through the emergence—and consolidation—of the Reform Movement, through the heyday of the Wissenschaft des Judenthums’s Movement, and through the surge of both the specific Russian Jewish civilization and the Hebrew and Yiddish literatures. He is a unique example of an Orientalic orientalist, marketing, with extraordinary success, an exotic biblical-Turkic community, an impossible combination, pretending to fulfill the role expected of him by the outer world. He was a Karaite Jew who was faithful to his religious and cultural heritage; he regarded his community as the only remnant of verus Israel, and he sought a means of ensuring the survival of his small community in a large and threatening world. It was not that the Karaites, God forbid, were not Jews in his eyes. On the contrary, the name of the Jews became usurped, in his eyes, by millions of Ashkenazi heretics and infidels.

The way he chose to separate his community from the encroachments of the Rabbanite majority was by presenting it to the authorities as an ancient exotic Hebrew group that split from the rest of Israel 2,000 years ago. He could consequently claim that his community was not responsible for those things that Christians accuse the Jews of, including the crucifixion of Jesus, the creation of the Talmud, various superstitions, and a parasitical way of life. Contrary to the widely held impression, Firkowicz never claimed that the Karaites of the Crimea and Eastern Europe were a separate people of Turkic origin, though he constantly stressed, obtusely, their Turkicness. Furthermore, the only connection that he made between the Karaites and the Khazars was the (inaccurate) claim that the Khazars received the Karaite and not Rabbanite version of Judaism. The significance of this claim was both polemical and apologetic. It reproached the Rabbanite Jews by implying that a large Turkic people received Karaite and not Rabbanite Judaism, and it removed the sense of offense felt by many Russians that in their early history they had been enslaved to vagrant Jews.

Firkowicz was terrified by the possibility that the Karaites would once again be at the same footing as the Rabbanites, for in the Rabbanite humiliation he saw the confirmation of the Karaite truth. He explained to the Russians that their forefathers were not subservient to the familiar jargon-speaking (that is, Yiddish) and Talmud-following Jews, but to other Jews, exotic and proud Orientals. He never presented this idea as an organized theory, but he sowed allusions and created an atmosphere. The theory was based on tombstone inscriptions from the Crimea, and on colophons and marginalia to manuscripts, both of which underwent careful “treatment” at Firkowicz’s hands and which became part of one of the most complex and systematic historical forgeries of all time.

Russian power, not always benevolent and sometimes capable of arbitrary destruction, was something that the young Firkowicz always kept in mind. Like many other local Karaites, Firkowicz spent much of his youth in the countryside, toiling over his land and trading with the Gentiles, working for a while as a flour miller and running other small businesses. Nevertheless, he studied, first by correspondence, with prominent Karaites in Halicz and the Crimea. He sought guidance in his studies from Rabbanites as well, mostly the maskilim (members of the Haskalah Movement), some of them in Austrian Brody, where Nachman Krochmal was then active.

Practically speaking, all the Karaite literature available at that time existed in manuscript form only, because the limited potential market for the Karaite books made printing commercially senseless. In this situation, Firkowicz was fully aware already as a young man of the fact that one should pursue handwritten books if one wishes to acquire knowledge. In Łuck, he copied a considerable quantity of manuscripts and was engaged in attempts to acquire others from other communities.

One of his local tutors in Łuck became his relative Mordekhay Sultanski (1771-1862), who served then as the ḥazzan (something like a rabbi with the Karaites) in Łuck and was one of the most important Karaite maśkils of his generation. Sultanski was interested in history, Bible criticism, Rabbanite Halacha, and apologetics emphasizing the parallels between the Karaite and Christian beliefs, ethics, and practices—a familiar subject with the Eastern European Karaites who had a history of being studied by Protestant scholars interested to find out the genuine, uncorrupted Judaism of Jesus, unspoiled by the Rabbinical Pharisees.

In the 1810s and 1820s, Sultanski penned in Łuck Zekher Ṣaddiqim, a historiographic work presenting his own version of Karaite history, the sources of which perished in a fire—such sources perishing in fire or flood and preserved only in copies or secondary sources would become familiar to Firkowicz scholars. The influence of Sultanski’s way of thinking and even of some minor details of his interests would be felt throughout Firkowicz’s career, and it is hardly possible to understand Firkowicz’s theories without comparing them against Sultanski’s background.

Firkowicz succeeded in his studies and was appointed as assistant teacher in Łuck, filling this role until 1820. But his temper was always his worst advisor. In 1817-1818, he got into a nasty quarrel with Sultanski, with the dispute being arbitrated in Gözleve (now Jevpatoria, Yevpatoria, Eupatoria) in the Crimea. The letters submitted to the Court of Gözleve or hidden from it included passages such as:

… he amassed a gang of followers whom he seduced to join himself in order to trample them and revile and provoke them and when they gathered together they dictated upon them dangers and falsehoods and entered them into the gates of the laws of the our lord, the Czar, may his Majesty be exulted, into danger and eternal shame, and afterwards, many a time they delivered those same writings and dangerous protests to the authorities and to such a great extent did they increase their malice that they raised their arms to strike them and we did not save them …

And,

You knew what I brought about with the shame that I caused to my lord my brother the sage, our honored master and rabbi, Mordekhay of Łuck [Sultanski], may his light shine! whom I cursed and slighted together with you for you, too, were helping me [...] for we intended to raise high the name of our family to show in every place that also in our family there are sages [...] we used to sign the names of many members of our community on those letters, you and I, on our own without their knowledge, and this secret is unknown to anyone besides us [...] therefore make an effort, my beloved, my brother, to use a device to remove those letters from the above-mentioned sexton and take them and hide them [...].

The letters were published in: A. Kahana, “Two Letters from Abraham Firkovich,” Hebrew Union College Annual, Vol. III (1926), pp. 359-370.

In the end, in the early 1820s, both men, Sultanski and Firkowicz, found themselves in the Crimea, which was di goldene medine for the poor, ambitious, educated, multilingual, smart, and sometimes unscrupulous Karaites of Łuck. For them, the peninsula was populated by rich, ignorant, vulgar Karaite Orientalics, who did not know what to do with their money but otherwise lacked for nothing that could not be provided by a private secretary from Luck.

Though ignorant and vulgar, the Crimean Karaite Orientalics knew how the world worked: The consiglieri from Łuck could be trusted as long as they had no local support base. When Sultanski married into an important local family, he immediately lost his job with the richest man in the Crimea and Novorossia, Śimḥah b. Šelomoh Babowicz (1788/1790?-1855). His replacement was Firkowicz, who had arrived in the Crimea accompanied by boxes full of his books, according to his much later testimony.

Simhah Babowicz wanted to become the political leader of the Crimean Karaites. Following the death of Binyamin Ağa Ne’eman Sinani-Çelebi b. Šemuʾel Ağa (the venerated leader of the community dating back to the period of the Crimean-Tatar Khans), Babowicz began to aspire to become the official head of the community. Forty years later, Firkowicz would assert that he himself was appointed in 1823 as the ḥazzan of the city and the chief Karaite teacher, but this claim seems to be a bit misleading.

In the 1820s, Firkowicz was engaged in literary and educational activities. He generated plans to re-establish a printing press at Gözleve in order to publish Karaite prayerbooks and classical Karaite works, using good manuscripts at his disposal. The first book he planned to publish was Firkowicz’s own Sepher Qodeš ha-Qodašim, dealing with the Tabernacle. However, in 1827 Śimḥah Babowicz withdrew his support from the project because of financial difficulties and, probably—if we believe Firkowicz’s much later version—because of Sultanski’s interference. Nevertheless, we know that in 1826 Sultanski finished paying his debts to Firkowicz, and both then renewed their business partnership, trading in books; in wine that was kosher for the Rabbanites; and in leather for tephillin, phylacteries used by the Rabbanite Jews but not by Karaites. As their secret language for written correspondence, both men used ungrammatical Yiddish written in non-Yiddish orthography. However, Sultanski’s financial situation continued to be helpless, and whilst on a visit to Łuck in 1827, he was arrested by the police because of his earlier debts there.

In 1822, Scottish missionaries were given a free hand to work in Southern Russia. Two societies were established there under the patronage of Czar Alexander I: the Russian Biblical Society and the Society of Israeli Christians. Both were headed by Prince Golitsyn, whose wife was deeply influenced by Barbara-Juliana Krüdener, a mystic who was close to Alexander I and had convinced him to create the Holy Alliance. Krüdener was also a strong believer in the idea that all Russians and Europeans originally came from the Israelite Lost Tribes. The Golitsyns owned an estate in Qarasubazar (now Belogorsk) in the Crimea, the residence of Babowicz. Firkowicz first met Krüdener there, probably in 1825.

At the turn of the 19th century, Anglo-Israelism—an inner-Anglican, sect-like movement—arose in England. Anglo-Israelism went hand in hand with conversionist efforts, which were spurred on in 1809 by the foundation of the London Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews. Besides the conversionist effort, Anglo-Israelism was closely connected with the search for the ancient fatherland of the supposed Israelite ancestors of the English, the Goths, which was supposed to be in Southern Russia (roughly, what is now Southern Ukraine).

In the mid-1820s, Southern Russia and the Crimea briefly became a mecca for English and Scottish missionaries, most of whom were believers in Anglo-Israelism, i.e., in a connection between the Samaritan Exile, the transfer of the Jews to Scythia (Southern Russia and the Crimea), and their association with the Goths, who were later to become the British. The title of a book by one of these missionaries, full of valuable information, including some details about the Karaites and their texts, speaks for itself: E. Henderson, Biblical Researches and Travels in Russia, London, 1826.

Anglo-Israelite ideas were also propagated by Dr. Moses Margoliouth (1819–1871), a Polish Jew who became an Anglican minister near London. In his History of the Jews in Great Britain (1846), Margoliouth claimed the authenticity of some forged Hebrew inscriptions from England and Spain that were allegedly very old. Firkowicz was involved with some of these missionaries, who gave him printed Hebrew Bibles bound together with a Hebrew translation of the New Testament to be distributed among Jews. Firkowicz bartered these printed copies for ancient Jewish manuscripts deemed by their owners to be sacred documents, but which no longer had any use-value. The Jews tore off the Hebrew New Testament and kept the printed Old Testament.

Apparently, Firkowicz also shared some of the missionaries’ views (he held the maskilim of Brody and the Scottish missionaries in high esteem even decades later). In a text he wrote in Russian, he claimed he “recognized” remnants of Slavic words in Hebrew texts he had allegedly found “in the Khazar city of Mangup” in the Crimea—evidence of the common ancestry of Jews and the inhabitants of Southern Russia (Ukraine). This short text is interesting as it reveals Firkowicz’s interest in Sarmatism and argues that the population of what had been Poland had non-Slavic origins. He also stated that the present inhabitants of Southern Russia have more in common physically with the Semites than with the Japhetides, so the Malorossians (Ukrainians) should be Semitic.

During the late 1820s, Jewish maskilim from Central Europe and prominent figures in the Wissenschaft des Judenthums, the Jewish Aufklärung, and Haskalah also began to show a keen interest in things Karaite. In this, they were following the earlier Christian, especially missionary and Protestant, model. It was generally felt that certain characteristic features of the Jewish religion (i.e., the Rabbanite version of Judaism) were still preventing civil rights from being granted to the Jews and that they, the Jews, ought to work toward meeting the requirements. This is why the men of the Jewish Aufklärung sought a suitable past in their search for the “original,” “uncorrupted” form of Judaism, which would serve as common ground for Jews and Gentiles. Some imagined this pure Judaism might be found in the Orient, preferably, an Orient without the Orientalics, like the Medieval Muslim Spain. Other men in the maskilic and Reformist movements imagined they would find it in the history of Karaism. This tendency found its expression in the correspondence between Mordechai (Isaak Markus) Jost (1793–1860) and the Crimean Karaite tycoon Babowicz, with Firkowicz playing a direct role in encouraging this search as Babowicz’s secretary.

Especially noteworthy in this context is Beṣalel Stern, who was asked by leading European-Jewish scholars to collect information on the Karaites in Southern Russia. Born in Brody, in Austrian Galicia, the city of the aforementioned distinguished Jewish thinker, Nacḥman Krochmal, of whom he was a pupil, Stern was appointed in the late 1820s to supervise the famous Odessa Jewish Seminary established in 1826, which served as the flagship of the radical Russian maskilim. Stern also served as the religious head of the Brody emigrants in Odessa who leaned toward Reform Judaism. Prior to the establishment of the famous Brody Synagogue in Odessa, religious services were held in his house (Brodsky meant not only “one from Brody” but also “one of Reformist-leaning outlooks”).

In 1827, Czar Nicholas I promulgated an order requiring the conscription of Jews, including small children, for army service (the so-called “Cantonists”, or ha-ḥaṭûphîm, “the snatched ones,” in Hebrew). One of the aims of this act was “liberating the Jews from the immoral influence of the Talmud and Hasidic Rabbis.” It should be observed that quite a number of the radical maskilim sided with such acts of the government. There is a great book called Drafted Into Modernity about the long-range effects of the “Cantonism” written by Prof. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern of Chicago NWU.

Nicholas I’s decree applied at first to the Karaites as well and in the Crimea and other places where members of the community were conscripted (seemingly, only one of them). However, Babowicz traveled to Saint Petersburg and succeeded in having the decree revoked. The money it cost him in bribes and gifts would be replenished by the Russo-Ottoman war, for which he was one of the Russian army’s chief suppliers.

A Hebrew book was published to celebrate the New Karaite status, “The Deliverance of Israel” (Tešuʿat Yiśraʾel), describing the lobbying mission in the capital. Firkowicz himself translated “The Deliverance of Israel” into the Turkic language of the Crimean Karaites in 1841, whilst on his way back from the Caucasus, to be read at public occasion at the synagogues.

We don’t yet possess much information of Firkowicz’s whereabouts in 1829, but in 1830, S. Babowicz hired him again to serve as the tutor for his children and his secretary, bringing us to the main events of our story.

In 1830, Firkowicz accompanied Babowicz, his patron, on a pilgrimage to the Land of Israel, which Babowicz hoped would assist him in being recognized as the leader of world Karaite Jewry. On the way, Firkowicz collected ancient books for Babowicz’s collection, buying them from Karaites and Rabbanites alike and copying them for himself; he also had access to books presented to Babowicz by the nasi of the Egyptian Karaites. He also went to the genizoth, sanctuaries for old Hebrew documents or texts. This Babowicz’s collection would evolve into the “Babowicz and Firkowicz Collection”—and after Babowicz died of plague during the Crimean War, it would be sold by Firkowicz as “the collection of Abraham and Gabriel Firkowiczs,” what is now the “First Firkowicz Collection.”

The military conflict between Muḥammad Ali, the ruler of Egypt, and the heirs of Jazzar-Pasha of Acre, combined with a cholera epidemic, prevented the completion of the Babowitz-Firkowicz pilgrimage. On the way back to the Crimea, Babowicz and his retinue stopped in Istanbul, where Firkowicz settled and was appointed to a series of educational and ritual posts. The Karaite community was small, numbering no more than 30 or 40 families, many of whom originated in the Crimea. Presumably, this 43-year-old man hoped to finally attain a normal life, while Babowicz hoped Firkowicz would serve as his eyes on the Karaite community of Istanbul. Again, it all went wrong.

In Istanbul, Firkowicz translated, edited, and published a translation of the Pentateuch into an experimental Turkic language—spoken Istanbuli Turkish with heavy lexical and grammatical loans from the language of centuries-old Eastern European Karaite Turkic translations. The partly Greek and Greek-and-Turkish-speaking community did not like this new strange language, except for those Istanbul Karaites of Crimean origins who had been exposed earlier to the traditional language of Eastern European Karaite Turkic Bible translations, who now had their accustomed texts wrapped in the spoken Turkish of their new home.

Firkowicz, with the purpose of advancing his religious and cultural reforms, set up a circle of former Russian—Crimean and Łuckian—Karaites who were residents in Istanbul to support him. However, the native Karaites of Istanbul saw him as a Russian agent and his “Moscovite” associates as a group of dangerous religious reformers. A short while after the publication of the translation of the Torah, almost all the copies were contributed to the Crimean Karaites; a planned translation of other biblical books was never printed.

Meanwhile, the Cohens, Šemuʾel and his sons Yiṣḥaq and Afeda, the leaders of the Karaite community of Istanbul, blamed Firkowicz for the illness and death of the little Berakhah Cohen, Firkowicz’s pupil, that might have occurred on account of lessons during the rainy winter nights. To thwart the Cohens’ attacks against him, Firkowicz attempted to set up some kind of “court for moral matters.” He arranged an inquiry related to suspicions leveled against Šemuʾel Cohen of moral misdemeanors with a married woman whilst he was in Jerusalem: that he

was alone with a married woman for more than half a year in a house in Jerusalem, the holy city, according to his own testimony.

We have the nonsigned testimonies that were gathered together with an attached map of the area of the Karaite section of Jerusalem. The purpose of the map was to confirm that the witnesses were capable of seeing what they claimed to have seen. One of the witnesses gave the following testimony:

and in the matter of the honored R. Šemuʾel Cohen she responded that he would be alone with her in one house and would lie down by her side and would kiss her and she saw with her own eyes also when he accompanied her to Istanbul, he kissed her—she saw it by her two eyes—and she told that she heard from Šaḥina Yeru’ that her uncle [Šemuʾel Cohen] told her that he should lie in her breast in order to warm him on account of the cold ... and she would also help him to urinate, indeed he did not know nor feel when she took his penis in her hand to make him urinate and even when she gave him an enema he did not feel and who knows if at such times she became like a daughter for him, and the secrets are the preserve of the Lord, our God ....

The woman referred to was indeed known for her slanderous behavior, and the witnesses testified that she used to spend the night in the houses of “the uncircumcised” (i.e., Christians, presumably Greeks) and befriended “the Amalekites” (Armenians). Clearly, such a blatant affront by Firkowicz against the father of the heads of the community could not leave the sons indifferent.

On Passover and afterward, the Karaite synagogue and neighborhood witnessed ugly spectacles. The quarrel between Firkowicz and the Cohen brothers included public insults, curses, fistfights, and thrown objects in the synagogue during prayers on the Sabbath and during Passover services. Afeda pulled at Firkowicz’s hair, which he had let grow long “for a reason known to me,” and called him “papa which is the name of the Gentile (Greek) priests,” hinting at Firkowicz’s assumed Christian sympathies. On Passover eve, Šemuʾel Cohen also attacked Firkowicz verbally and physically in the synagogue during prayers. Firkowicz was forcibly evicted from the synagogue, and Yosef Ṣaddiq “cried out in a loud voice that the earth would swallow up the synagogue on account of the Moscovites and the ḥazzan that they had brought from the Crimea.”

The next morning, which was the festival of Passover, Yiṣḥaq Cohen locked the synagogue to prevent Firkowicz and his Crimean followers from entering, and the prayers did not take place on time. However, Yiṣḥaq Cohen finally relented and opened the synagogue, but when he began to lead the service angrily after the hour for the prayers was over, Firkowicz corrected aloud and with satisfaction Yiṣḥaq Cohen’s mistakes in pronunciation of Hebrew words. After completing the prayers, Yiṣḥaq Cohen squabbled with Firkowicz in the synagogue.

Immediately after Passover, Yiṣḥaq Cohen took a number of symbolic steps that were meant to degrade the Russian Karaites who resided in Istanbul. The members of the community were prohibited from donning white felt hats (such hats, popular among the East European Karaites, can be seen in pictures of 19th century Crimean Karaites). He invalidated ritual slaughter done by persons with long hair, a fashion that characterized the Łuck Karaites, Firkowicz among them.

By the end of 1832, Firkowicz had returned to the Crimea, and for a while he was integrated into the religious Karaite establishment there. Had he held out in Istanbul for another half year, until January 1833, his lot might have been very different. The Russian navy and marines came to Istanbul to save the Ottoman dynasty from the advance of Muḥammad Ali into the heart of Anatolia, and the relations between Russia and the Ottoman Empire enjoyed a short—and unparalleled—romance.

Meanwhile, Śimḥah Babowicz, YaŠaR Łucki, and Abraham Firkowicz together set up a Karaite printing press in Gözleve, which was fast becoming the new center of the Crimean Karaites. Firkowicz was involved in the printing issues, however, the orderly activity of the printing press suffered from the tensions between Łucki and Firkowicz. The press published several books that Firkowicz had edited. In 1834 it published his book Sélaʿ ha-Maḥlóqeth, and afterward, Qiṣṣur Takhlith ha-Yešuʿah. In 1836 he published Ḥotham Tokhnith, which was full of sweeping accusations against Rabbanite Jews, “who killed our master, ʿAnan the Naśi,” and in particular against Hasidim. Two years later, he published his even more caustic book, Maśśah u-Meribah, which aroused strong protests by Rabbanite Jews. The book was even forbidden by the censor since it stated that the Rabbanites murdered

the righteous, pure, upright, God-fearing Jesus, the son of Miriam, who saved most of the nations from their former idolatry ... who was of the race of the Sons of the Scripture [Karaites], as explained in the book Sta dekarorum(sic! *Secta de Karaorum) written by Tadeusz Czacki.

The book discussed, among other things, the origins of Karaite religion from the Second Temple period, in the spirit of Śimḥah Łucki’s and Mordekhay Sultanski’s theories, but used terminology such as “Scribes, Pharisees, ṣaddiqim” (“righteous ones,” not *ṣaddoqim, which means “Sadducees”).

To satisfy the censors and the Rabbanite Jews, two subsequent editions, at least, were prepared, in which the expressions most offensive for Rabbanite Jews and Christians were somehow softened, and in some cases, “Muslims” were printed instead of “Christians” or “Hasidim.” Nevertheless, the scandal was still on high. Babowicz attempted to destroy all copies, however, a few survived, and the book is now rare.

In 1837, Firkowicz took part in the festive reception prepared to Nikolay I in Çufut-Qalʿeh by Babowicz. As a consequence of the royal visit, a separate Karaite religious authority was established for the first time in Karaite history, called Karaimskoje Duxovnoje Upravlenije / Beit ha-Dîn šel Gözleve.

Sometime later, the Crimean authorities presented the Karaite leadership with a series of questions about the origins of the Crimean Karaites, their moral and religious differences from the Rabbanites, and the time when they first came to the Crimea. In a personal communication, the Viceroy of Novorossija (Southern Ukraine) Count (later Prince) M.S. Voroncov (Vorontsov, Vorontzov) recommended Babowicz to try to prove that the Karaites have had no dealings with the Talmud (seen by the government and the maskilim alike as the source of all Jewish troubles) and Talmudic Jewry.

It was only half a year after the questionnaire was issued that Babowicz assembled the Karaite worthies for a session, during which Firkowicz presented his plan based on hunting for manuscripts in different communities, including searches in genizoth, and assembling data from tomb inscriptions. The plan was accepted, and Firkowicz and a young and well-educated Karaite from Odessa, Šelomoh Beim, were appointed to carry out the mission.

This was how the next, most important, stage in Firkowicz’s life began in the autumn of 1839, when he became involved in exploring the antiquities of the Crimea. There were to be years of travel through the Crimea, North Caucasus, Western Gouvernements, Egypt, Syria, and the Land of Israel. The result was three manuscript collections that are among the most important of such collections in the world, consisting of various historical treasures, a tangled network of purposeful forgeries, and sheer nonsense.

Part two of this story coming tomorrow!

Dan Shapira is an interdisciplinary historian and philologist at Bar-Ilan University. He is working currently on medieval and early modern Jewish minority communities, the Crimea, and the Khazars.