Inventing the Karaites

A story of historical forgery and fraud that saved a Jewish community from conscription and death, at the price of their authentic history and faith

In the days of Nicholas the First, the great Czar and emperor (may he live forever!) who ruled all the Russias and other places, in the year 1827 according to the Christians and in the year 5588 since Creation according to us, the Children of Israel ... a royal order was given. ... It was a new law to be established for generations to come, one unknown in earlier days. It was the king’s express command that letters be sent by messenger to all the officials in his kingdom in which it was explicitly stated that men from among the Jews be taken for military service in equal measure to other nations and tongues under his rule ... The Jews would not be permitted to buy men of other nations or to give substitutes other than their own nation’s sons. ... Great was the mourning, fasting and weeping among the Jews when the king’s order reached each province. The hearts of all were broken, spirits were faint, and knees dripped with water ... Rabbinic courts decreed that the women of Israel should take off their beautiful ornaments and not beautify themselves with gold, silver, jewels or pearls. Our Rabbanite brethren did this in all their communities ... As the word “Jews” was written in the text of the decree, and as it was understood afterwards in some places that the decree was to include each and every Jewish sect and did not exclude the Karaites, the officials in the Crimean towns included us Karaites in this decree as well.

With these words, Joseph Solomon Lutski (1770-1844) began his Epistle of Israel’s Deliverance, an account of how a Karaite delegation went from the Crimea to St. Petersburg, where they successfully petitioned Czar Nicholas to exempt Karaites from the new legislation. Although Karaites did not claim that they were not Jews—after all, the Epistle celebrated Israel’s deliverance—one can already detect the beginnings of a split between the two Jewish religious movements. Eventually, Eastern European Karaites denied any connection whatsoever to the Jewish people.

When, where, and how Karaism began is a matter of dispute, but there were clearly Karaite Jews by the end of the ninth century. Their central doctrine that the written Torah stands on its own without an oral Torah, as embodied in the Talmud, was a major intellectual challenge to Rabbinic Judaism. After a golden age in the land of Israel in the 10th and 11th centuries, Karaism was fully developed as an offshoot or alternate version of what we now know as Judaism. Major Karaite communities flourished in Byzantium (today’s Turkey), Egypt, Iraq, and other countries alongside the majority Rabbanite populations. Both groups spoke and wrote the same languages, composed commentaries on the Hebrew Bible, shared theological concepts, suffered the same disabilities, and, most important, saw each other and were seen by non-Jews, simply as two different forms of Judaism.

Karaites arrived in Eastern Europe (the Crimea, Poland-Lithuania, and Volhynia-Galicia, now western Ukraine) anywhere between the 13th and 15th centuries. In the Ottoman and Tatar possessions of the Crimea, the local Karaite and Rabbanite Jews paid taxes to the local Muslim governments and helped each other in times of trouble. They dressed similarly in Tatar dresses and spoke the same Tatar language; the disparity in their numbers was not great. In the rest of Eastern Europe, for the first time in history, Rabbanites and Karaites spoke different languages, Yiddish for the vast numbers of the former, and unique Karaite Turkic dialects for the tiny population of the latter. Nevertheless, they paid taxes to the Polish government as one group. Most telling, perhaps, they both suffered massacres perpetuated by the Ukrainian leader Bohdan Khmelnytsky in 1648-49.

The Karaite communities were generally quite small, but their intellectuals were fully engaged with the entire Jewish tradition, citing Rabbanite as well as Karaite sources, and writing Hebrew treatises on a variety of topics. A good example of an 18th-century Karaite intellectual who knew the whole range of the Jewish literature is Simhah Isaac Lutski.

During the late 18th century, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was partitioned between Prussia, Austria, and Russia. In addition, in 1783 Russia took over the Crimean Khanate from the Ottoman Empire. After a long period of living peacefully in Eastern Europe with little overt discrimination, Jews suddenly found themselves as residents of new countries that were unwilling and unprepared to absorb them in large numbers. Jews soon became the objects of discriminatory laws, such as special taxation, and, in czarist Russia, long-term conscription into the army.

One can assume that all Jews wished to be exempt from these extra burdens. But the Karaites had what turned out to be a winning argument: They were not the type of Jews who should be subject to discrimination. They rejected the Talmud, historically an object of attack by European Christians, and claimed they were productive citizens who engaged in commerce and agriculture. Therefore, the Karaites argued, they should not be subject to the same burdensome laws as Rabbanite Jews.

The Karaites made the argument for preferential treatment for the first time to Maria Theresa, empress of Austria (1717-1780). There were small Karaite communities, numbering perhaps 200 souls, in Halicz, Kukizow, and in some other towns of Galicia, the area of Poland incorporated into Austria. A precedent was set when a royal decree was issued on October 1774 exempting Austrian Karaites from the marriage tax and half of the poll tax. The Austrians considered them “exemplary Jews,” who should set an example for their Rabbanite brethren.

It was soon the turn of Russian Karaites to request an exemption, when the czarist regime imposed a poll tax on Jews in 1795 which was double that imposed on Christians. Catherine II (The Great, 1729-1796) granted the Karaite petition presented by Solomon Babovich (d. 1817), the head of the Crimean community.

When the conscription legislation ending the Jewish exemption from the draft was passed in 1827, it was clear that the law’s intention was to separate Jewish youths from their families and subject them to missionary pressure. To prevent this from happening to the Karaites, another delegation was launched from Crimea to St. Petersburg to petition Czar Nicholas I (1796-1855). The head of this delegation was Simhah Babovich (1790-1855), son of Solomon and the richest man in the Crimea. He was accompanied by Joseph Solomon Lutski, who wrote the account, cited above, of the long and arduous journey. He intended it to be read in the Karaite synagogues annually in celebration of the Karaite success. Its title, Iggeret teshu’at Yisrael (“The Epistle of Israel’s Deliverance”), and the clear, Rabbinic Hebrew in which it was written, indicate that even after Karaites won exemptions from Jewish disabilities, they still saw themselves as “Israel.” At the same time, it was possible to see how cracks between the groups were forming. In 1863, Karaites, but not Rabbanites, received full recognition as Russian citizens, setting the stage for the more dramatic break that would follow.

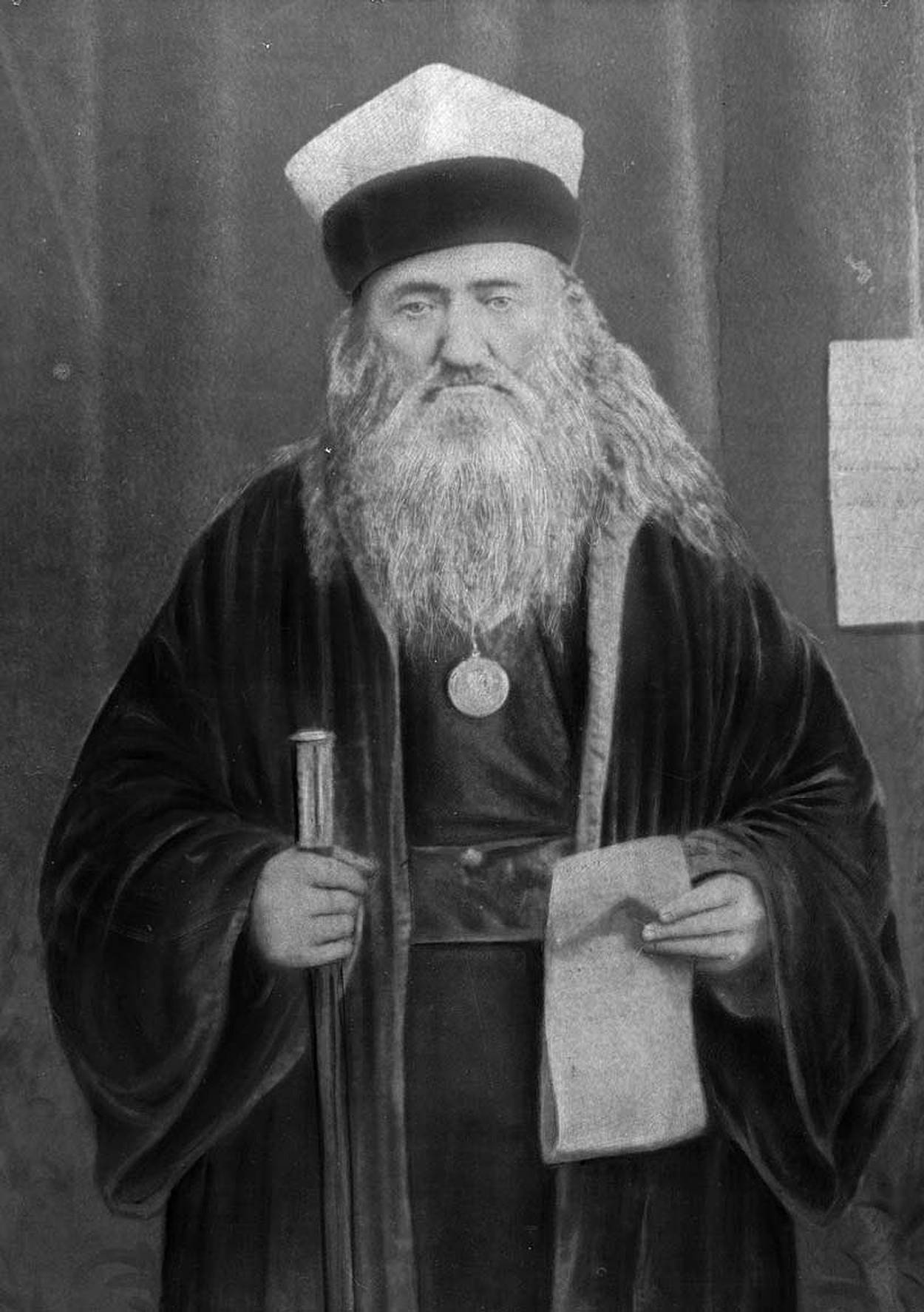

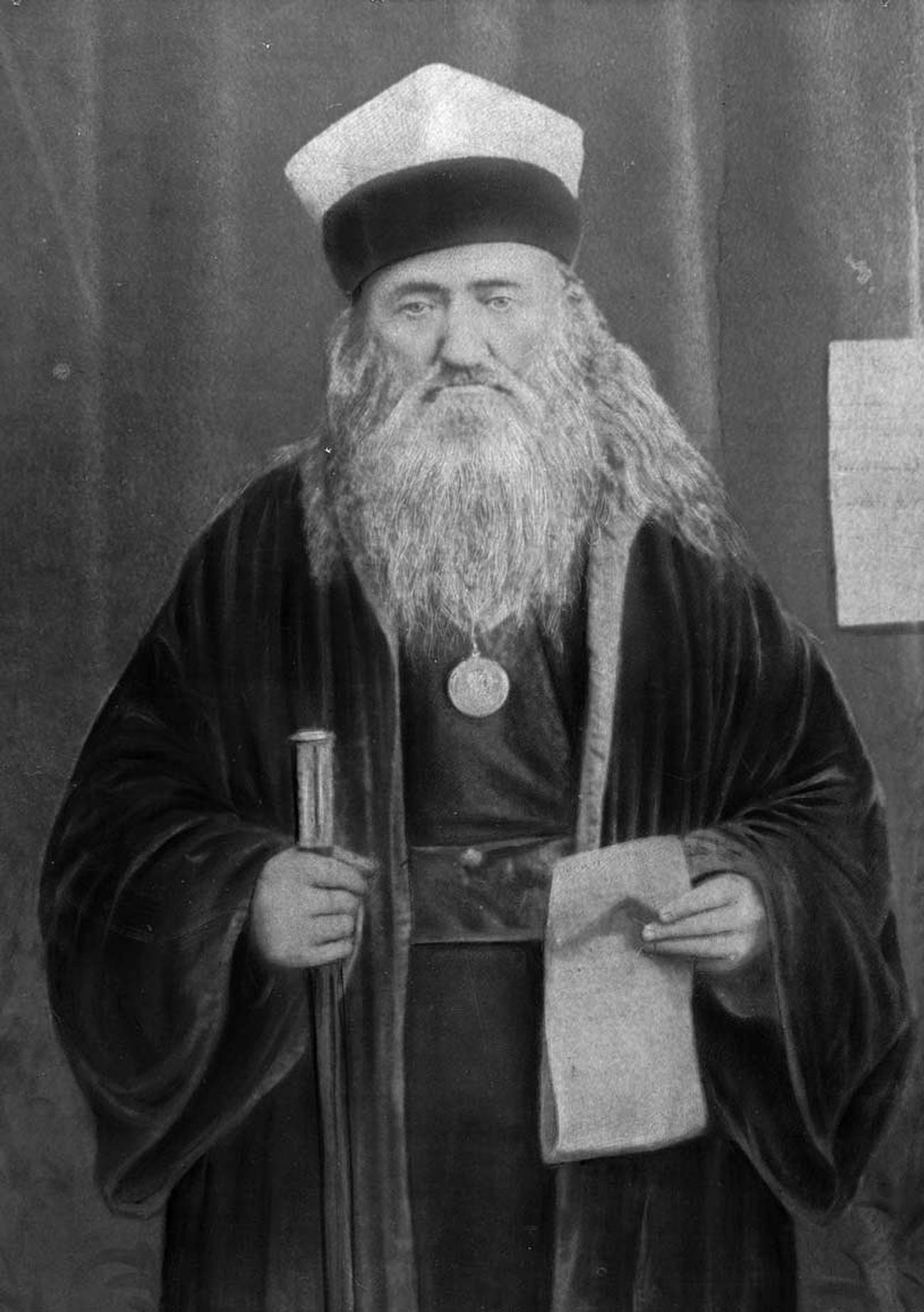

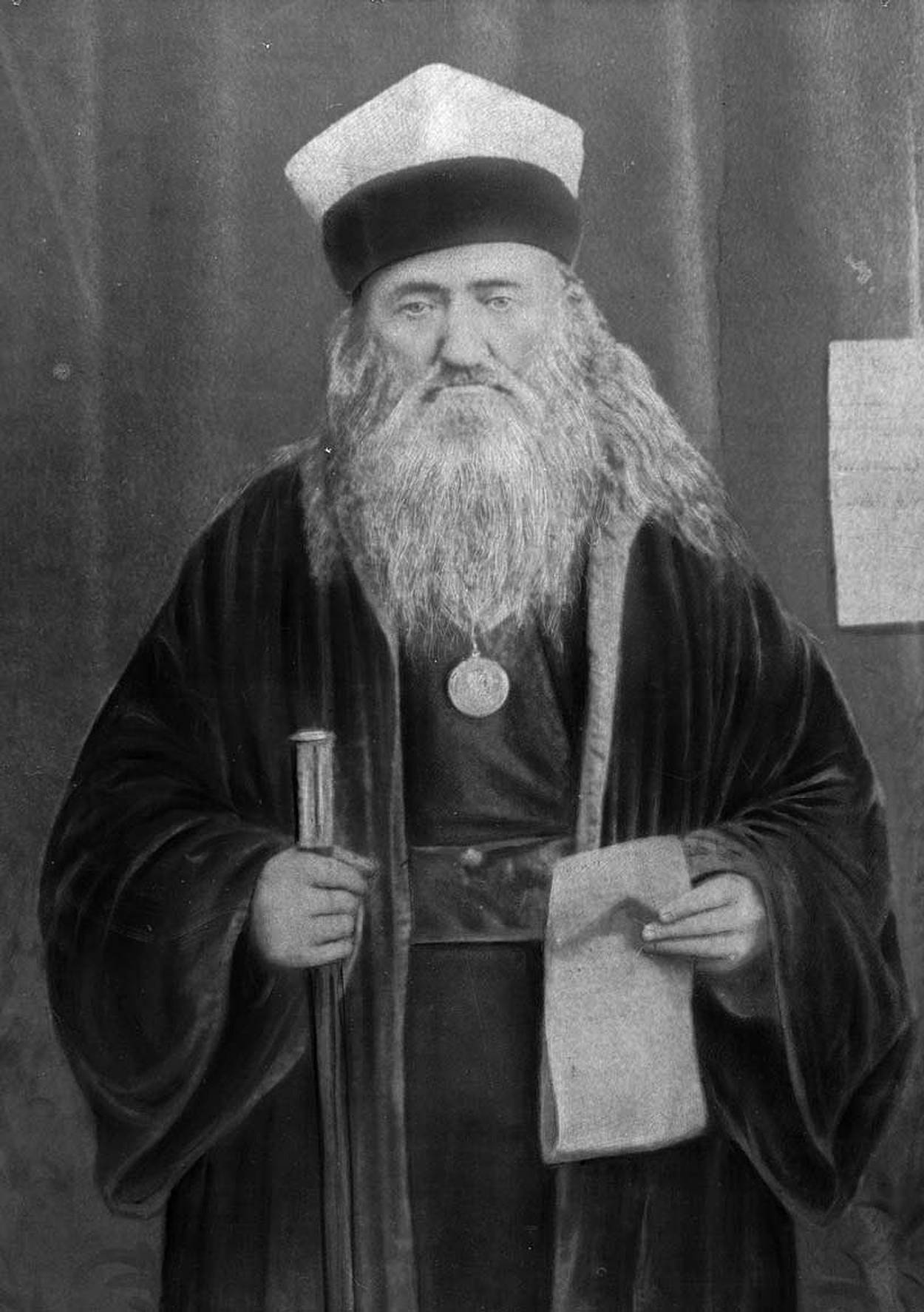

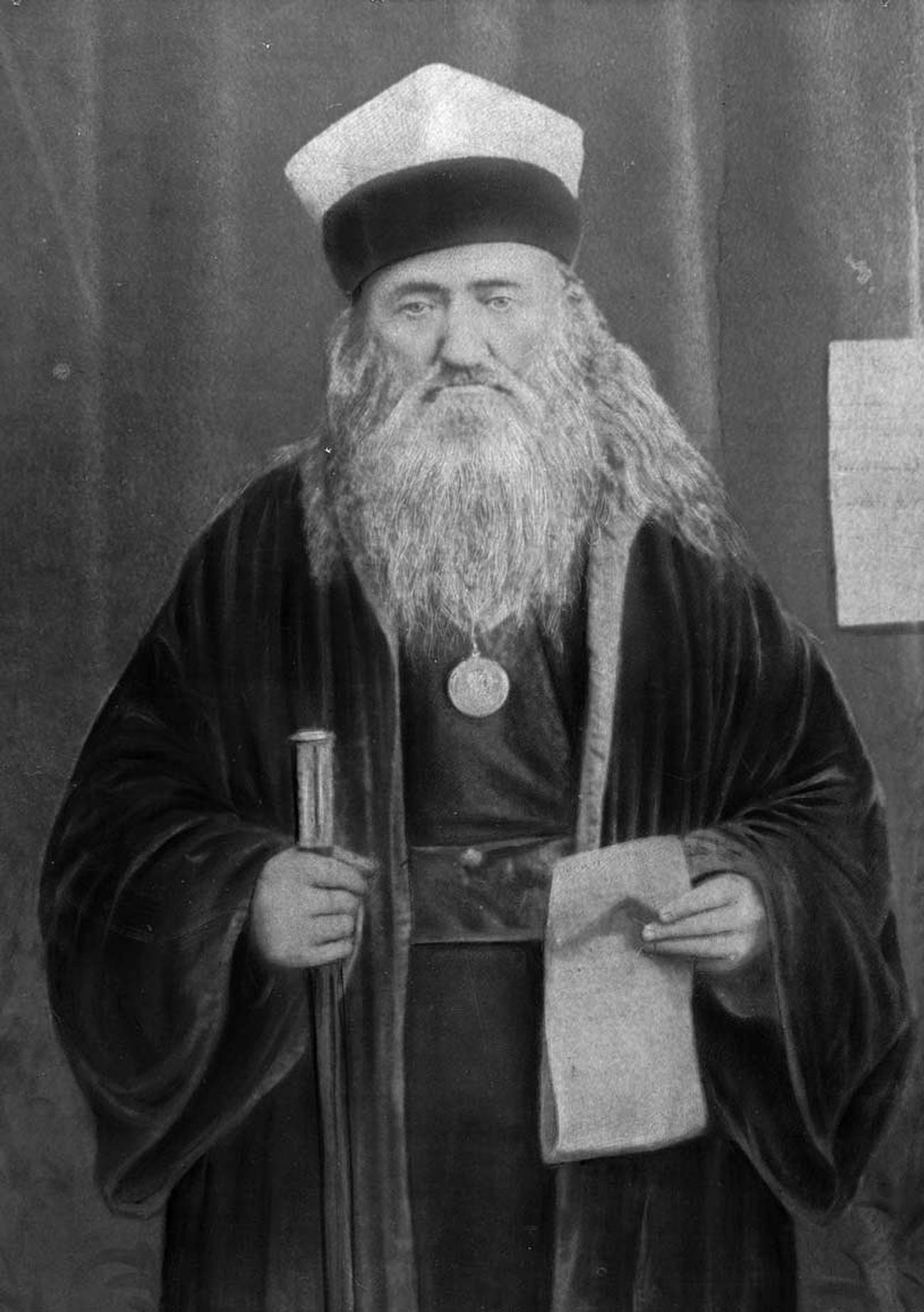

The outstanding Karaite personality of the 19th century was Abraham Firkovich (1787-1874), and it is often assumed that it was he who spearheaded the de-Judaization campaign of the Karaites. A closer look indicates that even though Firkovich was a stalwart defender of Karaites who was not above prevarication, forgery, and fraud to pursue his goals, he never denied that Karaites were part of the Jewish people—though the effect of his rewriting of history was in fact to reposition the Karaites in a way that eventually would save many from death, while at the same time leading to the longer-term dissolution of Karaite communities and belief systems.

Firkovich was a colorful figure, born in Lutsk in Volhynia, six years before the Russian annexation, who spent most of his adult life in the Crimea. He was at once a Karaite religious functionary, serving in leadership roles in his community and editing, translating and publishing Karaite treatises; who also engaged in commerce and lobbied for Karaite interests. He traveled often, visiting Karaite communities around the world and collecting their literary treasures. Firkovich was a leading force in the establishment of the Karaite printing press in the city of Gözleve (Yevpatoria), the Crimea, and even though the books published were censored to avoid trouble with the Christian authorities, they remain a valuable resource for the study of Karaism.

Firkovich saw himself as an historian and archeologist, but part of that role was fulfilled by forging historical artifacts and manuscripts in order to support his invention of an imagined Karaite past. He was in contact with members of the Jewish Enlightenment, some of whom romanticized Karaites for their independence from the Talmud, so they tended to accept what Firkovich said at face value without fact checking him too closely. Firkovich also attempted to couch his “findings” in the style of the emerging German-Jewish Wissenschaft des Judentums (Jewish Studies), giving them a scientific patina. Although a number of his contemporaries were aware of his forgeries, only recent research has discovered the extent of his scholarly dishonesty.

One of Firkovich’s favorite tactics was to substantiate the claim that the Crimean Karaite community had ancient roots by changing the dates on the tombstones of the Karaite cemetery in Chufut-Kale (literally, the Jews’ fortress), the main Karaite settlement on the peninsula. Since dates on tombstones are usually expressed by the numerical value of Hebrew letters, they are easily distorted. There are cases where Firkovich filled in a “heh” (ה, value 5000) and made it into a “tav” (ת, value 400), so that, for example, the original date of 5349 of the creation (1589 CE) as the date of death would become 4749 of creation (989 CE), 600 years earlier. Or, a “resh” (ר, value 200) would be elongated into a “qof” (ק, value 100), thereby pushing back the deceased’s death by 100 years.

Another tactic was to take manuscripts and either change the dates on them, or add extra materials. Firkovich took a Torah scroll found in Derbent on the Caspian Sea (now in the Republic of Dagestan, Russia) and added an inscription at the end of it indicating that it was written by descendants of the exiles after the destruction of the First Temple, who were brought to the Crimea by Persian kings Cyrus and Cambysis son of Darius. He also “found” a vellum in the nearby village of Mejelis with an expansion of the Derbent text.

Firkovich’s “discoveries” fit into the developing Karaite narrative that the Karaites were already in Crimea at the time of Jesus and, thus, unlike the Rabbanites, were not responsible for his crucifixion. Their residence there also predated the Talmud, a major focus of Christian antipathy toward Jews.

Another tactic was to claim that some Karaites were descended from the Khazars, a Turkic people who had converted to Judaism in the eighth or ninth centuries. To substantiate this assertion, Firkovich presented tombstones he had “found” in the Chufut-Kale cemetery of the main Karaite city of the Crimea claiming to mark the graves of Isaac Sangari and his wife.

Although Sangari is the name traditionally attached to the Jewish sage who led the Khazars to conversion, the name, and perhaps the person himself, is apparently fictional; the Khazars converted to Rabbanite Judaism not to Karaism. Unlike the act of changing of the dates of the deceased on existing tombstones, the tombstones themselves were absolute forgeries.

In sum, although Firkovich did not deny that the Karaites were Jewish, his theory of the antiquity of their residence in the Crimea as First Temple exiles, while hinting vaguely to some unspecified link to the Khazars, laid the groundwork for the eventual Karaite denial of any Jewish background altogether.

Yet there is another side to Firkovich’s legacy. As noted, through the years Firkovich amassed thousands of manuscripts, not always by the most honest methods. In his lifetime, he sold two collections of manuscripts, one Karaite and one Samaritan, to the Russian Imperial Library in Petersburg, and a third collection was transferred to that library after his death. Despite the occasional additions and changes to the manuscripts in his collections, most were left untouched. While the Soviet Union prevented access to these collections for most scholars for decades, they are now available once again. As a result, the Firkovich collections have greatly enriched our knowledge not only of Karaism but also of other fields of Jewish civilization.

When Firkovich died in 1874, Karaites had rights in czarist Russia but their identity was still more or less Jewish. They continued to pray and compose literature in Hebrew, while speaking Karaite Turkic dialects. At the same time, some Karaites were beginning to express a desire for de-Judaization. This was partly because the Karaites, in the Crimea especially, were economically very well off in the 1870s through the1890s, thus becoming supporters of the status quo at a time when Jews were getting a reputation in Russia as “revolutionary terrorists.”

As Jewish politics became identified as leftist, the Karaites fit well into the rightest wing of the political map, which was heavily anti-Jewish. The Karaites wanted a divorce from Jewish politics, though not from the Jewish faith as such. They did their best to ingratiate themselves to the czarist authorities, leading to increasing Russification and secularization of the members of the community and even some incipient attempts at building a separate Karaite national identity.

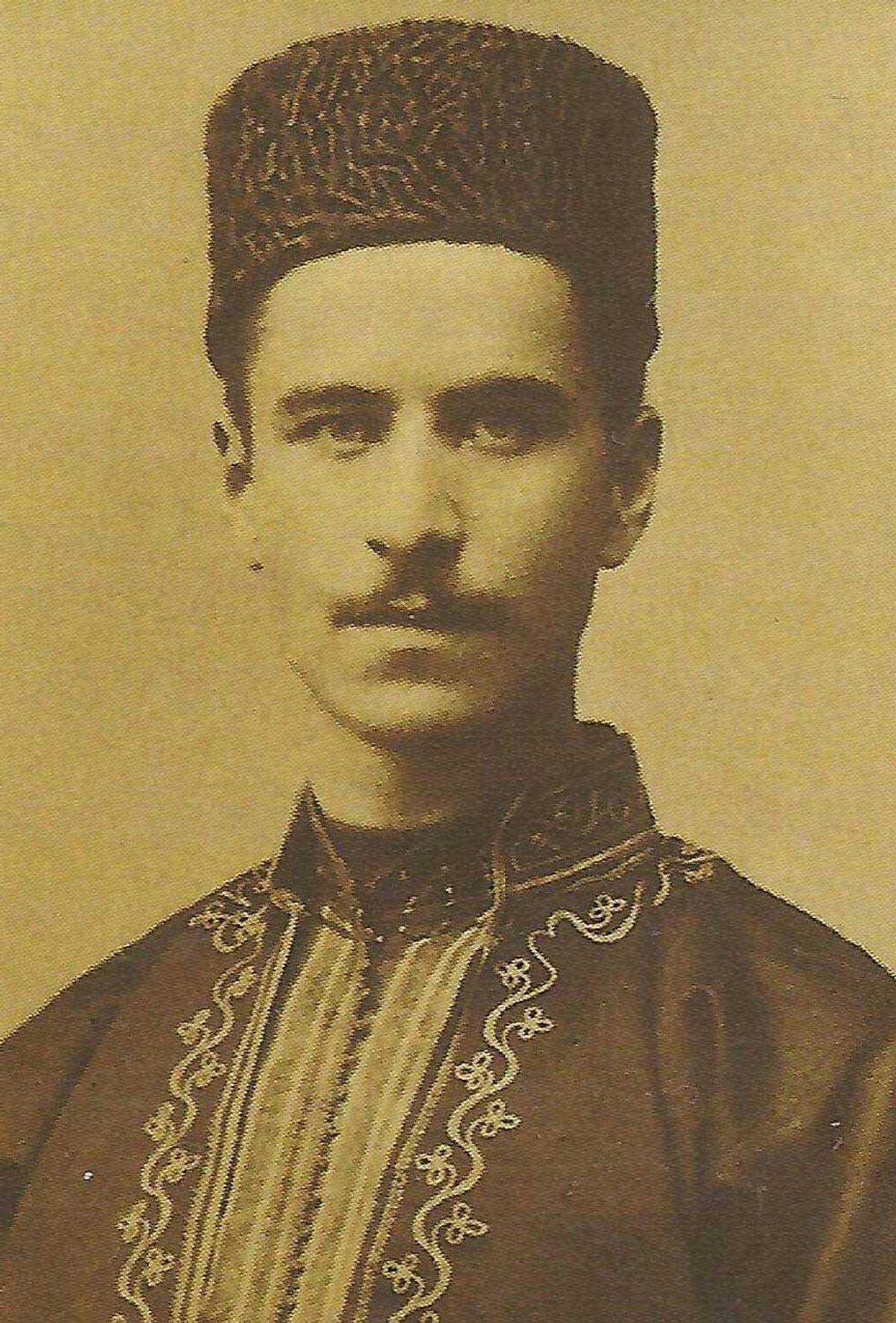

A good example of the new Russified, secular, nationalist Karaite was Seraya Shapshal (1873-1961), the man most responsible for Karaite “de-Judaization.” In 1896, as a student in the faculty of oriental studies of St. Petersburg University, he published a brochure in which he tried to demonstrate the Turko-Khazar origins of the Karaites. Shapshal graduated as a specialist in languages, and he started to work as a Russian political agent. In this capacity, he served as the tutor of the son of shah of Persia, and participated in suppression of the Persian revolution of 1908. Although he was mostly secular, because of his connections with the Russian government, he was elected to be head sage (hakham) of the Karaite community of his native Crimea and of Odessa in 1915. These connections had negative ramifications after the Communist revolution, and Shapshal was forced to flee Crimea in 1919-20, when it was occupied by the Red Army.

While in Crimea, Shapsal had already started to disseminate his thesis of the Khazar origin of the Karaites. In 1916, he abolished study of Hebrew by Karaite children. From 1919 to 1927, he was in Istanbul, Turkey, where he worked as librarian of the last sultan and then in banks. He was elected to be hakham of the Polish-Lithuanian Karaites, most of whom lived in the interwar Second Republic of Poland, where anti-Russian sentiments were very strong after over a century of occupation. As a sign of his opposition to the Hebrew language, Shapshal changed the title of his office to hakhan, a Turkic sounding word, similar to kagan, the title of rulers of the Khazar kingdom.

Shapsal began his de-Judaization campaign in earnest in 1928 in order to secure a better status for his community. There is no doubt that Shapshal drew some of his inspiration from the Turkish nationalism of Kemal Ataturk. Part of Shapshal’s reforms were to replace Hebrew with the Turkic Karaim language wherever he could, e.g., in the synagogue liturgy and on tombstones in the Karaite cemeteries. The language was now written in Latin letters, no longer in the traditional Hebrew characters. Loan words, especially from Hebrew, were replaced by newly coined Turkic words. Hebrew personal names were abandoned, and a new calendar, with the names of the months and the holidays replaced by “Turkic” names, invented by Shapshal, was devised.

Shapshal rewrote Karaite history as well. Suddenly, Jesus and Muhammad were considered Karaite prophets. Karaites were said to worship sacred oaks in the Chufut-Kale cemetery, thus turning Karaism into a syncretic religion that included elements of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and paganism. Shapshal also created a coat of arms, with pagan symbols, to replace the iconography of the Star of David and Ten Commandments in Karaite synagogues. The word “synagogue” itself was banned and replaced by the less-Jewish-sounding term “kenesa” or “kenasa.” Most importantly, the Karaites were declared to be descendants of Turkic tribes, with no historical affinity whatsoever to the Jewish people.

Despite the opposition of many traditional Karaites to these reforms, it did not take long for most Karaites to make their peace with the new historical and religious narratives they were given by their leaders. In Europe in the 1930s it was becoming more and more uncomfortable to be Jewish; Shapshal provided Karaites a way to opt out of Judaism while retaining their communal existence and rituals at an extremely dangerous historical moment.

In fact, Shapsal’s innovations were lifesaving for many Karaites. Although some Eastern European Karaites were killed during the Holocaust as Jews, the vast majority were spared. Their claim to be descended from Turkic tribes who had adopted an “Old Testament/Mosaic religion” was accepted by the Nazis and corroborated by Rabbanite scholars—who understood that if they admitted that Karaites were actually Jews, they would be signing a Karaite communal death warrant.

Sadly, relations between Karaites and Rabbanites, which were already strained, deteriorated even further during the Holocaust. There are reports of Rabbanite Jews who were refused in their attempts to get the Karaite authorities to list them as members of their communities. Some Karaites even fought in the German army. Seraya Shapshal, himself, lived in his apartment in Vilna throughout the war, disturbed by neither the Nazis nor the Russians when they captured that city.

The Karaite estrangement from the Jewish people continued under the Soviet Union, which persecuted religionists in general and Jews in particular. To the Soviets, the Karaites presented themselves not as believers in the Jewish religion but as a minority ethnic group. They no longer learned Hebrew, most abandoned their Turkic Karaim language, and they stopped practicing circumcision. In the 1970s when almost only Jews were allowed to emigrate from the Soviet Union, the Karaites did not claim Jewish status, remaining loyal to their invented historical narrative.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, with a worsening economic situation, Israeli incentives for immigrants, and a very liberal interpretation of the Israeli Law of Return, a number of Eastern European Karaites have moved to Israel (many of them with Christian family members). There are also reports that some of the remaining Crimean Karaites have started to investigate their Jewish roots. Yet most Eastern European Karaites still self-identify as descendants of Turkic, and now even Mongolic, peoples, with remnants of pagan shamanism. Lithuanian Karaites have partly integrated Christian elements into their prayer books. A remnant of Karaites are attempting to revitalize their language and folklore, but there are very few of them left.

The Karaite community in the State of Israel today is a recognized part of the Jewish people. In the last 200 years, and especially in the last century, however, historical trends in Eastern Europe led the Karaites there to abandon their Jewishness by inventing an origin story with no historical basis. In the words of the Passover Haggada, they have excluded themselves from the community. As a result, a once-vibrant and creative Jewish community has now virtually ceased to exist.

Daniel J. Lasker is the Norbert Blechner Professor Emeritus of Jewish Values in the Goldstein-Goren Department of Jewish Thought, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Be’er Sheva.