The Killing Fields of Ukraine

Massacres of over 100,000 Jews between 1918 and 1921 paved the way for the Nazi Holocaust-by-bullets

As Russian troops threaten Ukraine and President Vladimir Putin denies the very existence of the Ukrainian people, it is worth remembering the tragedy that took place between November 1918 and March 1921, when Russian and Bolshevik armies invaded the independent Ukrainian state that had been established in the aftermath of World War I and the Russian Revolution. All civilians, whether they identified as Ukrainians, Russians, Poles, Germans, Jews, or none of the above, became victims of that conflict, commonly referred to as a “civil war.” But the 3 million Jews who lived in the region—about 12% of the overall population—suffered a distinct fate.

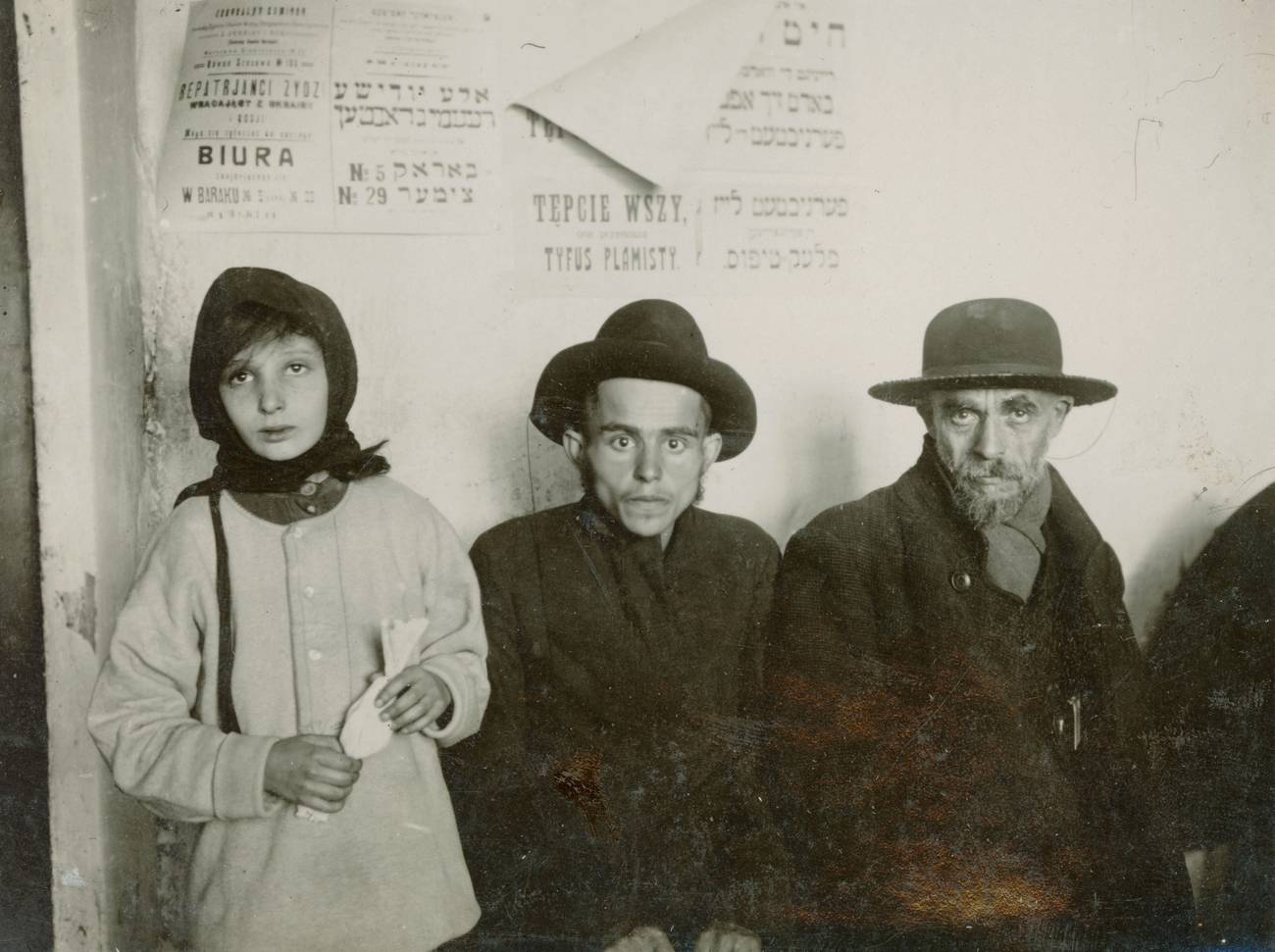

Between 1918 and 1921, over 1,000 anti-Jewish riots and military actions—both of which were commonly referred to as pogroms—were documented in about 500 different locales throughout what is now Ukraine. This was not the first wave of pogroms in the area, but its scope eclipsed previous bouts of violence in terms of the range of participants, the number of victims, and the depths of barbarity. Ukrainian peasants, Polish townsfolk, and Russian soldiers robbed their Jewish neighbors with impunity, stealing property they believed rightfully belonged to them. Armed militants, with the acquiescence and support of large segments of the population, tore out Jewish men’s beards, ripped apart Torah scrolls, raped Jewish girls and women, and, in many cases, tortured Jewish townsfolk before gathering them in market squares, marching them to the outskirts of town, and shooting them. On at least one occasion, insurgent fighters barricaded Jews in a synagogue and burned down the building.

The largest of the anti-Jewish massacres left over a thousand people dead, but the vast majority were much smaller affairs: More than half the incidents resulted only in property damage, injury, and at most a few fatalities. The numbers are contested, but a conservative estimate is that 40,000 Jews were killed and another 70,000 subsequently perished from their wounds, or from disease, starvation, and exposure as a direct result of the attacks. Some observers counted closer to 300,000 victims. Most historians today would agree that the total number of pogrom-related deaths within the Jewish community between 1918 and 1921 was well over 100,000. The lives of many more were shattered. Approximately 600,000 Jewish refugees were forced to flee across international borders, and millions more were displaced internally. About two-thirds of all Jewish houses and over half of all Jewish businesses in the region were looted or destroyed. The pogroms traumatized the affected communities for at least a generation.

The pogroms of 1918-1921 took place in the context of total war and a power vacuum. The Russian czar, who had ruled over most of the territory, enacting debilitating restrictions on his Jewish subjects, was deposed in February 1917 and murdered a year later. In his place, numerous entities vied for sovereignty. The Ukrainian People’s Republic, established in November 1918, promised to usher in a new era of peace and stability based on socialist principles and the promise of national autonomy for the Jews, including the right to use the Yiddish language and to administer their own internal affairs. There would be a minister of Jewish affairs, and Jewish schools, hospitals, nursing homes, orphanages, welfare and health institutions, all functioning in Yiddish and funded by the Ukrainian state. It was an offer eagerly embraced and celebrated by Jews in Ukraine and around the world.

However, this moment of mutual recognition did not last long. Within months of its foundation, the leaders of the Ukrainian state were forced to defend their newfound territory against anarchists, warlords, and independent militias, while fighting a “White” army seeking the preservation of a United Russia, a “Red” army trying to establish a global Bolshevik empire, and a Polish army intent on recovering its historic borders.

As is the nature of wars with no clear fronts, the enemy—whose identity could shift from week to week—could be anywhere and was often imagined to be in the rear, hiding among the civilian population. Accusations and rumors of collaboration ran rampant, encouraging individuals to stick closely to those most like themselves and to turn on those they perceived as different. Influenced by newspapers, broadsheets, and official proclamations, large segments of the population blamed the Jews for hoarding bread, importing hostile ideas, giving comfort to the enemy, and conspiring against the nation. At times, particularly in moments of regime change, these tensions were enacted in violence, often led by war veterans and deserters habituated to combat and unable to readjust to civilian life.

The ensuing pogroms were public, participatory, and ritualized. They often took place in a carnivalesque atmosphere of drunken singing and dancing; crowds allowed for diffusion of responsibility, drawing in otherwise upright citizens and ordinary people who in different circumstances might not have joined the proceedings. It was often the participation of these close acquaintances, trusted clients, and family friends that most galled the victims, instilling in them a feeling of powerlessness and alienation, a trauma that outlasted their physical wounds. Later in the conflict, the violence became more organized and methodical, carried out by military units acting on direct orders. These repeated attacks served no military purpose but rather expressed the sense that the Jewish civilian population was an existential threat to the new political, social, and economic order. To the distressed victims, who had expected the army to defend them and restore law and order, the attacks were a great betrayal.

Jewish civilians alone were singled out for persecution by virtually everyone. The Bolsheviks despised them as bourgeois nationalists; the bourgeois nationalists branded them Bolsheviks; Ukrainians saw them as agents of Russia; Russians suspected them of being German sympathizers; and Poles doubted their loyalty to the newly founded Polish Republic. Dispersed in urban pockets and insufficiently concentrated in any one contiguous territory, Jews alone were unable to make a credible claim to sovereignty. They could be found on all sides of the conflict, allying with the group most likely to maintain stability and ensure the safety of the community. As a result, no party fully trusted them. Regardless of one’s political inclination, there was always a Jew to blame.

The biggest threat to Ukrainian statehood, though, and the eventual victors in the conflict, were the Bolsheviks. Their promise of “land, bread, and peace” appealed to wide swaths of the peasantry, so their opponents sought to discredit them by drawing upon age-old prejudices and superstitions. It was widely recognized that some of the most prominent and popular figures in the Bolshevik movement were of Jewish heritage, most notably the Commissar of Foreign Affairs and leader of the Red Army, Leon Trotsky, who, while personally disavowing his ethnic and religious origins, continued to be recognized by the world as a Jew. The Bolsheviks’ enemies found they could turn the masses against him and the movement he represented by portraying him as a tool in a Jewish-Bolshevik quest for global power.

Only weeks after the declaration of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, militias acting as part of the republic’s army authorized attacks on Jewish civilians, branding them as Bolshevik agents. In the city of Zhytomyr, west of Kyiv, for instance, one of the first pogroms of the new era broke out when Ukrainian forces put down a Bolshevik uprising on Sunday, Jan. 5, 1919. With the uprising defeated, the victorious soldiers systematically pillaged the Jewish-owned stores in the central square and in an orderly fashion, street by street, broke shop windows with the butts of their rifles, smashed storefronts with their axes, and occasionally tossed grenades into stubborn doors they couldn’t otherwise pry open.

As so often happened in modern European wars, the Jews were blamed by all sides for the catastrophe and punished accordingly.

Hungry soldiers filled their trucks and carts with pilfered goods and took them in convoys to their station. Crowds of urban civilians then joined in the looting followed by peasants from the surrounding villages, who came into town with carts to carry off loads of stolen goods, returning to their villages with cloth and quilts slung over their backs. To many, it was a conflict of the countryside against the city. Fifty-three deaths were confirmed between Jan. 8 and 13, although many estimates put the number at closer to 90.

The following month, a Bolshevik uprising in Proskuriv, near the Polish-Ukrainian border, led to the dispatch of Ukrainian troops, who understood their orders to put down the rebellion as a license to attack Jews. Over the course of four hours, on Feb. 15, 1919, these soldiers massacred about 1,000 Jews in what was at the time possibly the single deadliest episode of violence to befall the Jewish people in their long history of oppression. The fight against Bolshevism, the perpetrators believed, demanded the elimination of the Jews. Indeed, as one report put it “beginning with Proskuriv the basic purpose of the pogroms in Ukraine appears to be the total destruction of the Jewish people.”

By June, the Ukrainian army had lost control of the region, which fell instead into the hands of peasant warlords and insurgent fighters, many of whom blamed the Jews for what they saw as the Bolsheviks’ betrayal of the peasant revolution. In the hamlet of Slovechno, north of Kyiv, for example, a local strongman led a pogrom in July 1919 on the pretext that the Bolsheviks were planning on shutting the churches and exiling the priest.

Over the summer and fall of 1919, the Russian White Army finally put an end to the chaotic rule of the warlords. Everywhere the Whites went, pogroms followed. In contrast to the earlier pogroms perpetrated by peasant soldiers, alienated troops from city garrisons, or local toughs, the White pogroms were instigated by uniformed Russian officers of the former czarist army sworn to uphold law and order, people of “refined manners” and “good upbringing” who read philosophy and played classical music but were also inculcated with the antisemitism of the old czarist elites. As the folklorist Shmuel Rubinshteyn put it, “The Jews had already lived through pogroms, but pogrom-mongers with university diplomas in their hands, with noble titles, with French words on their tongues—this was new to them.”

At the beginning of the conflict, Jews established self-defense brigades to protect their communities. But they quickly realized that the lightly armed civilian ward guards they could assemble were no match for the machine guns held by the attacking armies. Their only hope was to join and fight alongside the one force that was willing to defend them: the Red Army. Although the Bolsheviks had certainly been responsible for the occasional pogrom and some units, like the Red Cavalry that Isaac Babel made famous, continued to terrorize Jews, Trotsky and the leadership of the Red Army had no tolerance for pogroms. The Bolshevik Committee for the Struggle Against Antisemitism taught soldiers that the Jews were not the enemy and that pogroms were counterrevolutionary, and the Red Army punished those who engaged in anti-Jewish violence. As a result, Jews came to view the arrival of the Red Army, which would chase out pogrom-mongers and punish the perpetrators, with messianic expectation. When the Red Army gathered the Jews together in the market square, it was not to march them to death, but rather to arm them and recruit them. The subsequent influx of Jews into their ranks was a self-fulfilling prophecy: As more Jews joined up with the Bolsheviks, the popular association between the Bolsheviks and the Jews was strengthened.

When the Bolsheviks consolidated their rule over Ukraine in late 1920, their revolutionary tribunals punished those who had perpetrated pogroms. They rounded up thousands of peasant leaders from the countryside and sentenced them to death. Although they were acting under the name of the Bolshevik government, many locals viewed these courts, which were often led by individuals with Jewish backgrounds, as tools of the Jews. Over the next decade, the new Soviet government carried out its program in Ukraine: It closed down the churches, nationalized the land, and, in 1932-1933, created the conditions for a famine that killed some 3.5 million people. Many of the victims, once again, blamed the Jews.

I first became aware of the impact of these pogroms when I was participating in an oral history and linguistic research project called the Archives of Historical and Ethnographic Yiddish Memories, or AHEYM (the acronym means “homeward” in Yiddish). Together with my colleague Dov-Ber Kerler who directed the project, I traveled through Ukraine, interviewing elderly folks about their lives and how they survived the Holocaust and communism. I was struck at the time by the cataclysmic impact the pogroms of 1918–1921 had in shaping many of their lives.

It was in 2007 that I met Naum Gaiviker, who was a boy of 6 when his father was taken away during a pogrom in Proskuriv. Two years later, I met 91-year-old Nisen Yurkovetsky, who showed us the scar where, during the pogroms of 1919, the bullet that killed his mother had grazed him as she held him in her arms. The infant Yurkovetsky was rescued when a Polish priest noticed some movement in the mass grave that held the rest of his family.

After hearing a number of stories of this nature, I became curious about why nobody talked about these pogroms besides those who experienced them. Certainly, much has been written about the Kishinev pogrom of 1903, in which 49 Jews were killed. The pogroms of 1881, in which about two dozen Jews were killed, are often considered a major turning point in Jewish history. But the pogroms of 1918-1921, in which some 100,000 Jews were slaughtered, are largely forgotten, overshadowed by the Holocaust.

Yet at the time, the significance of what was happening in Ukraine set off alarms around the world. On Sept. 8, 1919, for instance, The New York Times reported on a convention held in Manhattan to protest the bloodshed then underway in Eastern Europe. “UKRAINIAN JEWS AIM TO STOP POGROMS,” the headline read; “MASS MEETING HEARS THAT 127,000 JEWS HAVE BEEN KILLED AND 6,000,000 ARE IN PERIL.” The article concluded by quoting Joseph Seff, president of the Federation of Ukrainian Jews in America: “This fact that the population of 6,000,000 souls in Ukrainia and in Poland have received notice through action and by word that they are going to be completely exterminated—this fact stands before the whole world as the paramount issue of the present day.”

A few months before the Times warned of the extermination of the Jews of Eastern Europe, the Literary Digest ran an article on the unrest in Russia, Poland, and Ukraine with the tagline “WILL A SLAUGHTER OF JEWS BE NEXT EUROPEAN HORROR?” These fears were enunciated in a comprehensive report by the Russian Red Cross that soberly concluded: “The task that the pogrom movement set itself was to rid Ukrainia of all Jews and to carry it out in many cases by the wholesale physical extermination of this race.” The American Jewish anarchist Emma Goldman, who spent much of 1920–1921 in the region, described a “literary investigator” she met in Odessa who had been collecting materials on the pogroms in 72 cities. “He believed that the atmosphere created by them intensified the anti-Jewish spirit and would someday break out in the wholesale slaughter of the Jews,” Goldman wrote. The Nation titled a 1922 feature article on the pogroms in Ukraine “THE MURDER OF A RACE” as though searching for a phrase to describe what would later be termed “genocide.” Writing from Paris in 1923, the Russian Jewish historian Daniil Pasmanik warned that the violence unleashed by the civil war could lead to “the physical extermination of all Jews.”

During the interwar period, Jews not only spoke about the violence of the pogroms in cataclysmic terms, they also acted accordingly. They fled the threatened region by the millions, radically altering the demography of world Jewry. They established far-reaching self-help and philanthropic organizations. They lobbied the Great Powers, pressing the newly established states of Poland and Romania to accept clauses guaranteeing the rights of minorities in their constitutions. They colonized new lands, setting the groundwork for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. They memorialized the pogroms in elegies and art. In the Soviet Union, one of the successor states to the ravaged region, they joined the civil service, government bureaucracy, and law enforcement expressly to prevent such atrocities from ever happening again and to bring the perpetrators to justice. And they acted, alone and in groups, to forestall what many adamantly believed was a coming catastrophe.

These actions cast suspicion on the Jews of Europe, whose desperate movements were seen as threatening what American President Woodrow Wilson had hoped would be a “just and secure peace.” The hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees arriving in Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, and Warsaw taxed the resources of these war-weary cities. Demagogic propagandists and pamphleteers stoked fears that the newcomers could be closet Bolsheviks, igniting a worldwide red scare and paving the way for the rise of right-wing political movements, not least of which were the Nazis. Governments responded by issuing new border regulations; Romania, Hungary, Poland, Germany, the United States, Argentina, and British Palestine—the countries to which the largest numbers of Jewish refugees were fleeing—each revised their immigration policies to foreclose further Jewish immigration and to insulate themselves from the Bolshevik menace. The pogroms had rendered the Jews “the world’s foremost problem,” as Henry Ford’s diatribe The International Jew put it in 1920.

The pogroms of 1918–1921 can help explain how the next wave of anti-Jewish violence—the Holocaust—became possible. Historians have sought explanations for the Holocaust in Christian theological anti-Judaism, 19th-century racial theories, social envy, economic conflict, totalitarian ideologies, governmental policies that stigmatized Jews, and power vacuums created by state collapse. But rarely have they traced its roots to the genocidal violence perpetrated against Jews in the very same region in which the “Final Solution” would begin only two decades later. The primary reason for this oversight has been a particular focus on the persecution of Jews in Germany, where anti-Jewish violence in the decades before Hitler’s rise to power was relatively rare, and on the Nazi death camps in occupied Poland, where the German bureaucracy modernized and intensified its killing methods. Even the systematic shooting operations common in German-occupied Ukraine were seen as categorically different from the type of localized frenzy of violence characteristic of pogroms. Pogroms, in short, seemed like relics of a bygone era.

But over the last several decades, historians have come to recognize that in the German-occupied regions of the Soviet Union, the killing was driven primarily by animosity toward Bolshevism and the perceived prominence of Jews in that movement, the same factors that had motivated the pogroms of 1918–1921. Detailed examinations of the massacres that occurred in Ukraine and Poland in 1941 have also revealed the complex ways in which political instability, social and ethnic stratification, and group dynamics turned “ordinary men” and “neighbors” into killers. These studies have expanded our allocation of culpability to include not just remote leaders like Hitler, abstract political philosophies like fascism, and large impersonal organizations like the Nazi Party, but also common people who made decisions on the local level. They have reminded us that about a third of the victims of the Holocaust were murdered at close range, near their homes, with the collaboration of people they knew. At the same time, a closer analysis of the pogroms of 1918–1921 shows them not only to be ethnic riots carried out by enraged townsfolk and peasants, but also military actions perpetrated by disciplined soldiers.

What happened to the Jews in Ukraine during the Second World War, then, has roots in what happened to the Jews in the same region only two decades earlier. The pogroms established violence against Jews as an acceptable response to the excesses of Bolshevism: the Bolsheviks’ forcible requisitioning of private property, their war on religion, and their arrest and execution of political enemies. The unremitting exposure to bloodshed during that formative period of conflict and state-building had inured the population to barbarism and brutality.

When the Germans arrived, riled up with anti-Bolshevik hatred and antisemitic ideology, they found a decades-old killing ground where the mass murder of innocent Jews was seared into collective memory, where the unimaginable had already become reality. As the demographer Jacob Lestschinsky presciently noted on the eve of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the “heritage of atrocities” left by the “Ukrainian horrors” of 1918–1921 had “still not fully healed.” The continued presence of Jews was a constant reminder of the trauma of that era, of the crimes that locals had perpetrated against them and their property, and of the terrible repercussions of those actions. The Nazi German genocide, with its unprecedented scale and horrifying death toll, offered the prospect of a type of absolution, the opportunity to remove the evidence of past atrocities and to relativize the sins of the previous generation, to allow the pogroms to be forgotten amid far greater villainy. As U.S. President Bill Clinton put it during a visit to Kigali, where he acknowledged his failure to prevent the 1994 Rwandan genocide: “Each bloodletting hastens the next, as the value of human life is degraded and violence becomes tolerated, the unimaginable becomes more conceivable.”

Today, there are about 40,000 individuals who identify as Jewish in Ukraine, including Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Anti-Jewish rhetoric has not played a significant role in the current conflict. But Putin, who perfidiously portrays Ukraine as a state defined by “hate and anger,” will surely use all the tools at his disposal to whip up popular resentment against Ukraine’s leadership and to discredit democratic Ukraine in the international arena. In any case, a Russian invasion will be a disaster for all inhabitants of Ukraine and, like the Russian interventions in 1918-1921, will lead to unintended consequences.

This article is adapted from Jeffrey Veidlinger’s book In the Midst of Civilized Europe: The Pogroms of 1918-1921 and the Onset of the Holocaust.

Jeffrey Veidlinger is Joseph Brodsky Collegiate Professor of History and Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan. He is the author, most recently, of In the Midst of Civilized Europe: The Pogroms of 1918-1921 and the Onset of the Holocaust.