Kurt Eisner, Gustav Landauer, and Adolf Hitler

How Munich became the world capital of antisemitism and the birthplace of the Nazi Party

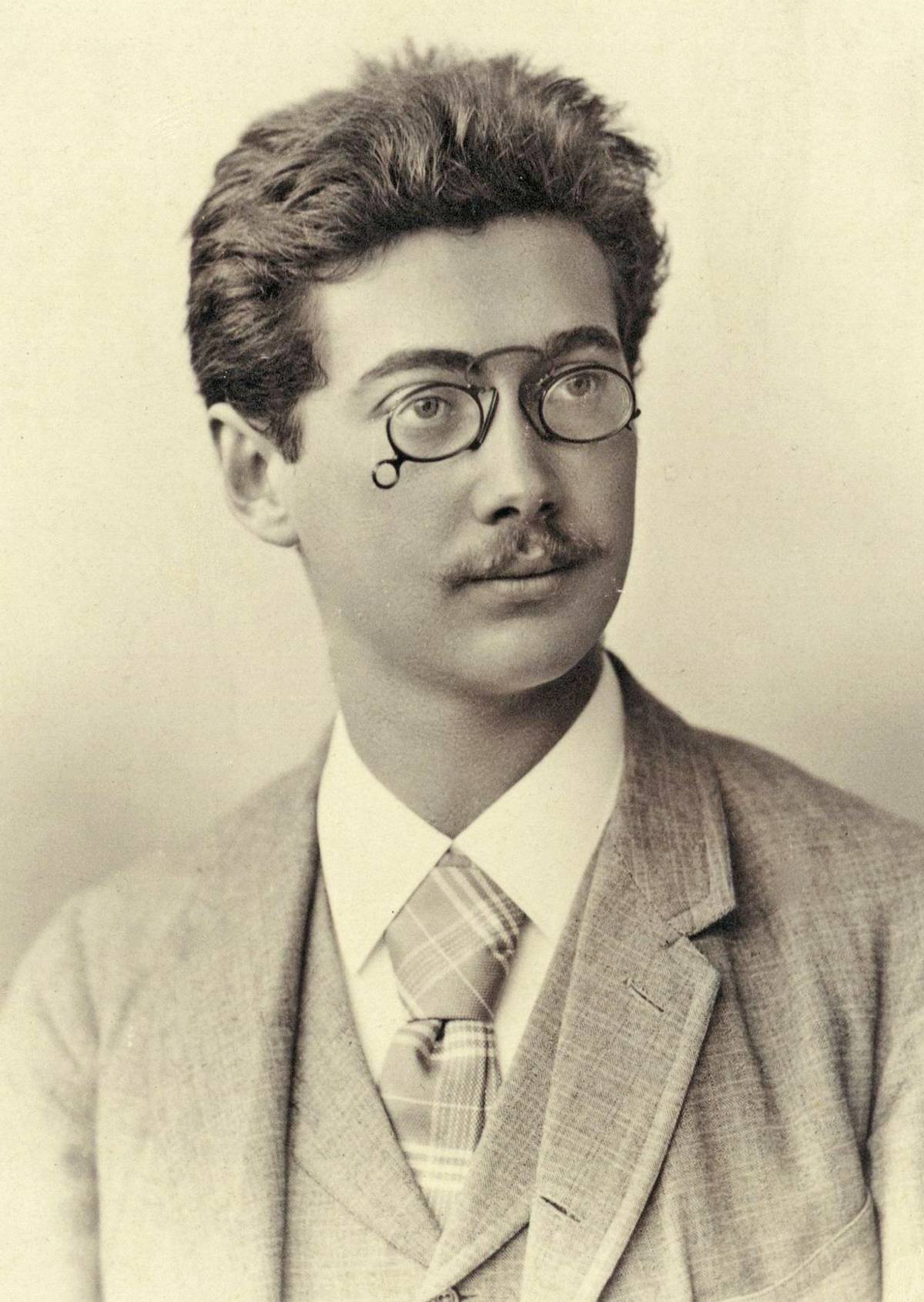

February 26, 1919, marked a unique moment in the history of Germany and its Jews. On this cold winter’s day, a crowd of a hundred thousand assembled at Munich’s Ostfriedhof cemetery to mourn Bavarian Prime Minister Kurt Eisner, the first Jewish head of state in German history. Eisner had toppled the Wittelsbach dynasty that had reigned in Bavaria for seven centuries. He and his socialist government had ruled Bavaria for three months until he was assassinated by a right-wing extremist. Another German Jew, Gustav Landauer, who would himself assume a powerful position in one of two short-lived council republics established in Munich in April 1919, held the eulogy for his friend Eisner. Both had long since broken with the Jewish religion of their ancestors, and yet both identified with the values of Jewish tradition as they defined it. Standing before the casket of his murdered friend, Landauer told the crowd: “Kurt Eisner the Jew was a prophet because he sympathized with the poor and downtrodden and saw the opportunity, and the necessity, of putting an end to poverty and subjugation.”

Kurt Eisner the Jew. Usually only his enemies rubbed his nose into his Jewish background. His estate includes a huge file of letters with crude antisemitic insults. Landauer, like other revolutionaries, also became the target of antisemitic attacks, and was gruesomely murdered when the socialist experiment was brought to an end by paramilitary forces in the first days of May 1919.

The first Jewish politician to be at the head of a German state became the target of all manner of anti-Jewish prejudices: To many outsiders peering in, this Social Democrat residing in the petty bourgeois Munich suburb of Großhadern was a Prussian Rothschild and Bavarian Trotsky all rolled into one. The Bavarian citizen who had grown up in Berlin was branded by his opponents as a Galician or, as if this was not sufficient, an Eastern Galician. The established journalist was characterized as a destitute Bohemian. To this mixture could be added any rumor one cared to spread—and this could be held not only against Eisner, but against Jews on the whole. Along these lines, the secondary school teacher Josef Hofmiller noted in his diary that Eisner had “his race’s trait of not feeling offended by any kind of rejection, but rather, if he has been escorted out through the front door, of sticking his head back in at the back door.”

One of the most depressing archival finds in connection with the revolution in Munich is a bundle of two thick files with hundreds of antisemitic hate letters against Eisner, which contain frequent incitements to violence. They include a postcard, addressed to the “Hebrew Residence” and a letter to the “King of the Jews” in which it says: “Control yourself, or disappear to the country where you belong, to Palestine! The broad masses of the German people will eradicate you, something one person can accomplish!” A member of the “Association for Self-Help” writes: “You’re no German, but rather a tolerated alien.” And a letter writer who calls himself a Social Democrat rants: “… we demand a National Assembly and not some common Jew gang dictatorship … The Jew gang has already taken a large share of stolen money abroad, and the families are living in splendor and joyously in the Switzerland …” The letters are teeming with expressions like “Jew pig,” “dirty Jew,“ and “uncircumcised scum Jew.” Eisner is called a “little dirty Jewish Polish schnorrer” and a “Russian Jew trickster.” The tenor of the letters is that Eisner is “after all, a Jew, not a German.” Or as another letter writer formulates it: “Your fatherland is not our German Reich; rather, it lies in Poland, Galicia, or Palestine, where the dirty Jews all come from and also belong.” Sometimes he is called Koschinsky, at other times Kosmanowski, and then again “Salomon Kruschnovsky, Jew from Galicia.” One postcard contains a picture of Eisner with his eyes punched out.

During the three months or so that Eisner was in office, the tone of these letters became increasingly inflammatory, and the threats they contained were increasingly directed not just at Eisner but at the “fellow members of his race.” The senders, some of whom were anonymous, others signed, were demanding that “Jews like this must now be hunted” or a “quick death for these executioners of Christianity.” Jews were not appropriate as heads of state, the letters said, they were merely tolerated aliens and should be sent to Palestine, or they simply said that “a Galician Jew should not rule over Germans.” This letter writer lets Eisner know that he would be “shot at the first opportunity” if he does not give up his office within four days. He did not even think it was necessary to send his letter anonymously. Another contemporary writing from Zurich, referring to the pogroms raging in Eastern Europe, says that the policies pursued by Eisner and members of his tribe were responsible for Jews being killed in Poland and that, should “many innocent people also come to harm in the German Reich, we would chiefly have the fellow members of your race to thank for that.” An observer who describes himself as artistically talented draws Eisner’s likeness on a self-made wanted poster with a reward on his head. Another one lists a catalogue of abuses in order to repeat the mantra that “the Jews” are responsible.

Even after Eisner was murdered, the tirades of hatred did not diminish. One day after the assassination Josef Hofmiller noted in his diary: “Eisner’s very behavior provoked his violent removal.” His students registered Eisner’s death with cheers. And in its obituary the Kreuzzeitung characterized the Bavarian prime minister as “one of the nastiest representatives of Jewry who have played such a characteristic role in the history of the last several months.”

In one of the first attempts at a historical account of the revolution and council republic in the conservative Süddeutsche Monatshefte, the economist and professor for housing construction at Munich’s Technische Hochschule, Paul Busching, repeatedly characterized Eisner and his companions by referring to their Judaism:

The little Jewish journalist, who had never been taken seriously in his own party, made himself—to the unanimous applause of the workers, including those immediately elevated to the status of “intellectual workers”—prime minister of an old, important German state and took up his dangerous office, initially accompanied only by some Jewish literati from Berlin.

It was hardly surprising that it was “the Russian Jews in the Wittelsbacher Palais” who were playing a decisive role in the events to follow “with fiery calls inciting the people.” They were the ones blindingly dazzling the people: “Certainly, under Jewish influence the intellectuals concluded their special pact with the council republic and had joyfully become proletarians for the time being.”

Even among German Jews themselves, the Jewish background of many revolutionaries was a fiercely debated topic. The majority of Bavaria’s Jews were decisively opposed to the revolution or sensed that, in the end, they would be the ones paying the price for the deeds of the Eisners and Landauers. The philosopher Martin Buber, a close friend of Landauer and an admirer of Eisner, had visited Munich at Landauer’s invitation in February 1919. He left Munich on the day Eisner was murdered and summarized his impressions of his visit to the city as follows: “As for Eisner, to be with him was to peer into the tormented passions of his divided Jewish soul; nemesis shone from his glittering surface; he was a marked man. Landauer, by dint of the greatest spiritual effort, was keeping up his faith in him and protected him—a shield-bearer terribly moving in his selflessness. The whole thing, an unspeakable Jewish tragedy.”

Not long before that, on December 2, 1918, Landauer was still urging Buber to write about these very aspects: “Dear Buber, A very fine theme, the revolution and the Jews. Make sure to treat the leading part the Jews have played in the upheaval.” To this day, Landauer’s wish has not been fulfilled.

While the connection between Jews and the Bavarian revolution has certainly been broached again and again, it has ultimately been relegated to a footnote in most historical accounts. Even in the flood of new publications occasioned by the centenary of the revolution, historians and journalists are reticent to point out that the most prominent actors in the revolution and the two council republics were of Jewish descent. Biographies of the chief actors emphasize that their subjects stopped viewing themselves as Jews any longer.

The reason for the reticence is obvious. As a rule, one skates on slippery ice when researching the Jews and their participation in socialism, communism, and revolutionary movements. The ices become very slippery indeed when dealing with a place that, so soon after the events of the revolution, became the laboratory for Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist movement. After all, it was mainly the antisemites who highlighted the prominence of Jews in this revolution to justify their anti-Jewish behavior. In Mein Kampf, Hitler himself entitled the chapter about the period when he was active in Munich after November 1918, “Beginning of my political activity.” He drew a direct line between what he called “the rule of the Jews” and his political awakening.

In conservative circles, the motif of a link between Jews and leftists served, if not as a justification, then certainly in many cases as an explanatory framework for antisemitism. Thus, Golo Mann, son of the writer Thomas Mann and himself a witness to the revolutionary events in the city as a high school pupil, referred explicitly to the Munich episode:

Not Jewry—there is no such thing—but individual people of Jewish extraction have, through their revolutionary experiments in politics in Central Europe, burdened themselves with serious blame. For example, there was the attempt to set up a council regime that was unquestionably made by Jews in the spring of 1919 in Munich, and that was indeed a criminal, horrible mischief that could not and would not end well.

Among the revolutionaries there were certainly “noble human beings” such as Gustav Landauer, Golo Mann concluded. “Yet we as historians cannot ignore the radical-revolutionary impact of Jewry with a gesture of disavowal. It had serious consequences, it fed the view according to which Jewry was revolutionary, insurrectionary, and subversive in its totality or overwhelmingly.”

An even sharper formulation of the same sentiment came immediately after the Second World War from the historian Friedrich Meinecke in his book The German Catastrophe: “Many Jews were among those who raised the chalice of opportunistic power to their lips far too quickly and greedily. They now appeared to all antisemites as the beneficiaries of the German defeat and revolution.”

For many contemporary witnesses as well as subsequent interpreters of these events, there was a clear causality: The conspicuous prominence of Jewish revolutionaries (most of whom, moreover, were not from Bavaria) prompted a reaction that created a space for antisemitic agitation to an unprecedented degree. Jewish contemporaries claimed to have recognized the link as much as antisemites did. From the vantage point of 1933, even revolutionaries referred to this connection, albeit from another perspective: On “the day my books were burned in Germany,” Ernst Toller wrote in the preface to his autobiography Eine Jugend in Deutschland: “Before the current debacle in Germany can be properly understood, one must first know something of those happenings in 1918 and 1918 which I have recorded here.”

Historians agree that we have no record of antisemitic or anti-communist views from Hitler before 1919. But opinions diverge on whether he went through an initially socialist phase in the first half of 1919 or was rejected by another party, whether he was already interested in politics or still apolitical. Anton Joachimsthaler was one of the first historians to draw attention to the importance of this phase for the formation of Hitler’s worldview. He stated categorically: “The key to Hitler’s entry into politics lies in this period of time in Munich, not in Vienna! The revolution and the reign of the councils that followed, events that profoundly shook the city of Munich and its people, triggered Hitler’s hatred of everything foreign and international as well as of Bolshevism.” According to historian Andreas Wirsching’s view, the special climate of Bavaria in the summer of 1919 provided Hitler with a stage to rehearse a new role in his search for authenticity:

What he learned by rote, amplified, and intensified demagogically, and what he also ended up believing, was initially nothing more than the kind of völkisch-nationalist, anti-Bolshevik, and antisemitic propaganda that was ubiquitous in Bavaria and its army … What turned Hitler first into the drummer and then the ‘Führer’ he became, then, was by no means an idea, a firmly established, granitic world view. Rather, he found his stage and the role that fit in with this rather more by accident.

We must be vigilant in recognizing that only knowledge about subsequent events allows us to assess Munich as a stage for Hitler and the ideal laboratory for the growing National Socialist movement. If it is suggested that Hitler and other antisemites really needed Jewish revolutionaries in order to spread their ideology, then one encourages the argument that, in the end, the Jews themselves were to blame for their misfortune. Yet historians cannot act as if the Jewish revolutionaries, socialists, and anarchists had never existed—as if their prominence during this brief moment of German history had not been there for all to see, and as if they had denied their Jewishness—just because these arguments may have been used in the past and are revived in today’s antisemitic propaganda. Let us try for a moment to turn the tables in our thinking about this: If subsequent history had turned out differently, one would have been able to regard this chapter as a success story for German Jews, as an episode of pride rather than of shame. Let us take a moment to imagine that Kurt Eisner’s revolution had taken root in Bavaria, that the Weimar Republic had survived, and that Walther Rathenau had remained foreign minister instead of having been murdered. We would then write a history of successful German-Jewish emancipation in which the religion and origins of Germany’s leading politicians did not stand in the way of their political advancement—a story reflecting what actually happened in Italy and France.

This was the very hope articulated by some Jewish contemporaries for a brief moment in November 1918. In their minds, the fact that Kurt Eisner became the first Jewish prime minister of a German state constituted proof of successful integration. Yet this perception was quickly overturned, and when Martin Buber spoke of a Jewish tragedy in February 1919, he echoed an opinion already shared by the larger Jewish public. Although the Jewish background of the Munich revolution’s protagonists did not necessarily play a central role in their self-perception, it figured in their complex personalities and reflections, and it was also something outsiders used to reproach them.

So were they really Jews? In what is widely regarded as his classic contribution to understanding the modern Jewish experience, Trotsky’s biographer Issac Deutscher has closely examined the figure of the “non-Jewish Jew” and, in so doing, traced the tradition that emerged in Judaism of the Jewish heretic. With a view toward Spinoza, Marx, Heine, Luxemburg, and Trotsky, he wrote: “They were each in society and yet not in it, of it and yet not of it. It was this that enabled them to rise in thought above their societies, above their nations, above their times and generations, and to strike out mentally into wide new horizons and far into the future.”

Deutscher’s explanation applied equally well to most of the Munich revolutionaries. They were not part of the organized Jewish community, and most of them did not have any kind of positive relationship with the Jewish religion or religion in general. Yet, in contrast to Deutscher’s non-Jewish Jews, some of them evinced an active interest in their cultural Jewish heritage: Like Sigmund Freud, they were “godless Jews”—Jews whose Jewishness could not be unambiguously defined in terms like religion, nation, or even race.

Historians, past and present, have speculated about why a relatively large number of Jews—Leon Trotsky, Lev Kamenev, and Grigory Zinoviev in St. Petersburg, Béla Kun in Budapest, and Rosa Luxemburg in Berlin—occupied leading roles in the revolutionary events of Europe during the period of upheaval between 1917 and 1920. Some scholars fall back on the conditions of earlier Jewish life to explain the high level of Jewish participation in these revolutionary movements. In the Tsarist empire, where most Jews lived, they were systematically oppressed and could not actively participate in politics. Many discovered in socialism an opportunity to escape their own desperate situation. In Germany, in theory, Jews could participate in politics since the establishment of legal equality in 1871, and they were represented in legislative bodies. Yet only in the left-liberal and leftist camps did they find what appeared to be full acceptance. For this reason most Jewish deputies in the Reichstag before the First World War were Social Democrats, even though the vast majority of Jewish voters voted for centrist bourgeois parties.

Even earlier, to be sure, starting with Karl Marx (whose anti-Jewish statements were well-known) and Ferdinand Lassalle, numerous pioneers of the labor movement had Jewish backgrounds. The secularization of the Messianic tradition, so deeply rooted in the Jewish tradition, and the aspiration to justice associated with the Biblical prophets, also with respect to other disadvantaged social groups, was an additional reason for the commitment of many Jews to revolutionary concerns. To the historian Saul Friedländer it seems “as if an unquestionably naïve but very humane idealism underlay what the Jewish revolutionaries were doing: a kind of secularized messianism, as if the revolution could bring about redemption from all manner of suffering. Many also believed that the Jewish question was going to disappear once the revolution was victorious.”

Whatever reasons propelled individuals to action, it is indisputable that neither before nor afterward in Germany had so many Jewish politicians stood in the public limelight as during the half year between November 1918 and May 1919. In Germany, the appearance of a Jewish prime minister and of Jewish cabinet ministers and people’s commissars was especially conspicuous because, in contrast to other European countries like Italy and France, Jews had not been entrusted with any governmental responsibilities in the period prior to the First World War. “Until November 1918 the German public had only known Jews as members of parliament and party functionaries, or as employees in municipal councils. Now, suddenly, they were showing up in leading government posts, sitting at Bismarck’s desk, determining the fate of the nation.” In 1919, however, contemporaries could not overlook what Robert Kayser, the literary historian and son-in-law of Albert Einstein, unequivocally articulated in the journal Neue Jüdische Monatshefte: “No matter how excessively this is exaggerated by antisemites or anxiously denied by the Jewish bourgeoisie: it is certain that that the Jewish share in the contemporary revolutionary movement is large; it is, at any rate, so large that it cannot be the product of any accident, but must have been dictated by an inherent tendency; it is a repercussion of the Jewish character in a modern-political direction.”

In Berlin, too, during this time Jewish politicians, such as Kurt Rosenfeld as head of the Justice Ministry and Hugo Simon as Finance Minister, had governmental responsibilities, and with Paul Hirsch there was even a Jewish prime minister in Prussia for a brief time. Yet in no city was the participation of Jews in the revolutionary events as pronounced as in Munich. Here great numbers of people with Jewish background stood among the most prominent exponents of the revolution and the council republics. In addition to Eisner, these included his private secretary Felix Fechenbach and finance minister Edgar Jaffé (already baptized at a young age), as well as Landauer’s comrades-in-arms in the first council republic, Ernst Toller, Erich Mühsam, Otto Neurath and Arnold Wadler. The mastermind of the second council republic was the Russian-born communist Eugen Leviné. There were other Russian communists active in his circle, such as Tovia Axelrod and Frida Rubiner. The only city that exhibited any parallels to Munich in this respect and at this time was Budapest. István Déak wrote that “Jews held a near monopoly on political power in Hungary during the 133 days of the Soviet Republic [established] in [March] 1919.” And, as in Munich, Budapest’s Jews became scapegoats for all the crimes of the revolutionary era.

Even after Eisner’s assassination, and just a few weeks before his life came to a violent end, Gustav Landauer was corresponding with Martin Buber and the young Zionist (and later President of the World Jewish Congress) Nachum Goldmann about his participation in a conference of Jewish socialists scheduled to convene in Munich at which discussions about the kibbutz idea and other Zionist ideals were planned. Landauer agreed to participate: “I believe the conference can be fruitful.”But before that could happen, more important events intervened.

On April 7, after prolonged hesitation and against the resistance of the Communists, writers with anarchist inclinations, with Ernst Toller, Erich Mühsam, and Gustav Landauer in the lead, proclaimed the “Council Republic of Bavaria” (“Räterepublik Baiern”). It was Landauer’s 49th birthday, and he was at the peak of his political career. In the Council Republic he had become the People’s Commissar for Public Education, Instruction, Science, and Arts. The writer Isolde Kurz noted a year later: “In the bookstores all you saw was socialist and communist literature; the most widely read author during those days was Gustav Landauer …” The day the council republic was founded—also Gustav Landauer’s birthday—was spontaneously declared a national holiday. As Kurz described things, Munich’s population took note of all this with indifference:

We also got a national holiday, so in droves the people of Munich went for a walk in the warm glow on dry sidewalks, here and there studying one of the new government’s gigantic posters without a wince, at most someone would just sigh “That’s something!” and then continue strolling on in peace … It was like a ball falling into a woolen sack. Nobody answered, either to approve or contradict. The soul of the crowd seemed entirely absent.

Just a week later, the First Council Republic collapsed. The Communists, who only one week earlier had nothing but scorn and derision for the Landauer-Toller-Mühsam regime, now seized power. Under the leadership of the Russian-Jewish journalist Eugen Leviné, the Russian-born ethnic German Max Levien (frequently and falsely labeled a Jew because of his name), and the Munich-born city commandant and Red Army leader Rudolf Egelhofer, a second and significantly more radical council republic emerged as of April 13. Gustav Landauer could no longer identify with its politics and submitted his resignation from all of his political positions.

When “White” troops, who were made up of Freikorps members and Reichswehr soldiers, crushed this Second Munich Council Republic on May 1 and 2, Landauer’s fate was initially uncertain. Worried that he would become a target of the right-wing troops despite his disassociation from the radical Communist regime, his friends rushed to save his life. Martin Buber called for the creation of a committee that would publicly advocate for Landauer. His initiative met with approval from Fritz Mauthner:

I assume that we are completely in agreement on the matter: Saving, if possible, the valuable and so lovely person of G.L., without approving any particular politics … We cannot protect him from himself, and he would also reject that … Very sad that it is exactly the idealism of his circle—not to mention some Russians I find suspicious—that is allowing a new wave of antisemitism to take storm over Germany. The rage in Bavaria is alarming.

These efforts to assist came too late. On May 1, sitting at the desk of Kurt Eisner, Gustav Landauer was arrested by right-wing Freikorps members and brutally murdered the next day in the Stadelheim prison in Munich. In his last letter to Fritz Mauthner on April 7, 1919, less than a month before his murder, he had written: “If I’m allowed a few weeks of time, then I hope to accomplish something; but it is easily possible that it will only be a few days, and then it was all a dream.”

Just like after Kurt Eisner’s assassination, the Zionist paper Jüdisches Echo again published a moving obituary for Landauer: “Gustav Landauer did not enter into any relationship with local Jewish circles and Jewish politics … Yet there is evidence from Landauer’s earlier works of the serious humane feeling and inner sympathy with which he approached the problems of Judaism.” The article in the Jüdisches Echo called it a sacred duty to honor his memory. As a sign of its solidarity the newspaper reprinted Landauer’s essay on East and West European Jews (“Ostjuden und Westjuden”). Despite their political differences, Martin Buber kept faith with his friend after death and posthumously dedicated the seventh of his “Speeches on Judaism” to him with the title: “The Holy Path: A Word to the Jews and to the Gentiles.”

Rarely, too, did the conservative Munich press fail to point out the Jewish background of the revolutionaries, especially when there was something negative to report. Thus, in its coverage of the prosecution for embezzling files from the Eisner government by his former private secretaries, the paper began by listing the defendants this way: “The 26 year-old Israelite merchant Felix Fechenbach from Mergentheim, now in Chemnitz, the 24 year-old Israelite private student Ernst Joske …” And the General Secretary of the Bavarian Peasants’ League wrote in the association’s paper, Das Bayerische Vaterland: “How the Jews Eisner and Fechenbach are perpetrating a monstrous crime on the German people.” Further down, antisemitic language is used to describe Fechenbach as follows: “Eisner is dead, but the Jew Fechenbach is still running around on his flat feet somewhere in the world …” The Völkischer Beobachter expressed itself even more clearly on the anniversary of the revolution. This paper was ready with one brief explanation for all the evils supposedly caused by Kurt Eisner. The answer to the questions raised about why Eisner was prepared to commit his allegedly disgraceful deeds was this: “Four words supply the answer to all the above questions: ‘He was a Jew.’”

The writer and later Nobel Prize Laureate Thomas Mann was perhaps the most prominent early observer of the transformations sweeping his adopted city in the wake of the failed revolutions of 1919. Within a few short years, Munich had changed from a center of “cheerful sensuality,” “artistry,” and “joie de vivre” to a city decried as a “hotbed of reaction, as the seat of all stubbornness and of the obstinate refusal to accept the will of the age” that could only be “described as a stupid city and, indeed, as the stupidest city of all.”

Munich’s Jews, who with the exception of a few families, had long since discarded their strict orthodoxy, cultivated the same Bavarian dialect as their Christian neighbors. They loved the mountains and vacationed in the summer on Bavaria’s lakes. They were loyal supporters of the Wittelsbach monarchy. Jewish textile firms like the Wallach Brothers, merchants who specialized in retailing and exhibiting traditional folk costumes, pioneered the dissemination of lederhosen and dirndls. Munich Jews headed the Löwenbräu brewery and the FC Bayern München soccer club. Some were bankers and department store owners, physicians and attorneys, society ladies hosting salons, and secretaries. Others were rag dealers and beggars, East European immigrant Jewish factory workers and artisans.

They were royalists and revolutionaries, religious Jews and atheists. They pointed with pride to the central synagogue in the city center, a building shown on many postcards defining the silhouette of the city alongside the twin domes of the Frauenkirche. From the outside it looked like a neo-Romanesque church. Services included organ music, a regular feature of liberal-oriented communities although they also represented an affront to Jewish religious laws for the Orthodox minority. Five years later the latter erected the smaller but equally splendid Orthodox synagogue Ohel Jakob (Jacob’s Tent). The synagogue buildings reflected Munich’s steadily increasing Jewish population, which had grown from 2000 in 1867 to 11,000 in 1910.

The antisemitic excesses of the period following the war would have been unthinkable if they had not been planted on fertile ground. Anti-Jewish resentments had struck deep roots going well back into the early modern era. They repeatedly pushed to the surface especially during political upheavals. Eisner and his comrades did not cause antisemitism; the events associated with them merely reactivated it.

What had fundamentally changed now was the ubiquity of the “Jewish question.” It would be worthwhile to investigate systematically how rarely the word “Jew” appeared in the press before the First World War and how frequently it occurred after the war. Starting in 1919 there was hardly a week that went by without reporting about Jews as communists or capitalists, draft dodgers or war profiteers—or articles featuring disclaimers of reporting like this. There was talk about foreign or alien elements, the customary code words for Jews, alongside terms like profiteer, trafficker, or black marketeer. The right-wing press held the Jews responsible for losing the war, for the revolution, and for the Schandfrieden (the “ignoble” or “disgraceful” peace treaty) of Versailles. But in the centrist and leftist press, too, there was constant talk about Jews: when they reported on the revolutionaries and their bloody demise; when deportations of East European Jews were discussed; when a Jewish cabinet minister was murdered and a member of parliament publicly challenged; when a Jewish merchant was beaten up on the street; and when graffiti was scrawled on synagogues.

It made no difference that the Jews made up less than two percent of Munich’s population. The “Jewish question” had a presence in public perceptions in Munich long before it was apprehended in the same way in other parts of the German Reich.

Before Munich became the capital of the National Socialist movement, it had already become the capital of antisemitism in Germany. It laid claim to this title in the immediate postwar era thanks to many factors: to the high concentration of antisemitic groups, from the Thule Society through the Freikorps to the National Socialist German Workers’ Party; to the radical antisemitic network of ethnically German emigrants from the Baltics surrounding the later Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg and his dissemination of antisemitic concoctions from the Czarist Empire; to the antisemitic publishing house of Julius Lehmann and newspapers like the Völkischer Beobachter; and (finally) to the graffiti smeared on synagogues, desecrations of cemeteries, and brutal attacks on Jewish citizens. Antisemitism had penetrated into the center of Bavarian politics, into its law enforcement forces, its legal system, and its mainstream media.

There was thus no public authority capable of defusing the explosive mix concocted in Munich following the First World War. On the contrary, in the “Ordnungszelle” (“cell of order”) he created, the Bavarian prime minister and later state commissioner general Gustav von Kahr saw to it that this mixture would also actually detonate. In 1920 and 1923, just a few days after he had taken office as prime minister, he initiated the deportation of Jews who held citizenship in Eastern European countries. Leading figures in Munich’s police headquarters, including the chief of police Ernst Pöhner and the head of the political division, Wilhelm Frick, openly manifested their antisemitism and were among the earliest Nazis in the party organization. While crimes committed by people on the left were punished severely, Bavarian judges praised crimes committed by people on the right as heroic, patriotic deeds and handed out mild sentences for them. As of 1920, the most important Munich newspapers had also steered into right-wing channels. As early as June 1923, as far as Thomas Mann was concerned, Munich had already become “the city of Hitler.”

Hitler’s failed attempt to seize power on November 9, 1923, only appeared to mark the beginning of the end for the rise of an antisemitic movement in Germany. In spite of the failure of his putsch, the marginalization of the Jewish population had been successfully tested. Identifying the revolution as a Jewish undertaking, branding Jews as draft dodgers or shirkers or war profiteers, attempting twice to deport East European Jews, and committing extreme acts of violence during the night of November 8 and early morning of November 9, 1923—collectively, all these actions sent a clear signal to Munich’s Jews. While the city’s population continued to grow, the number of Jewish residents declined significantly between 1910 and 1933, falling from 11,000 to 9,000. Some of the city’s most famous Jews left Munich and Bavaria. Jewish travelers were urged to avoid Bavaria. Nobody could have known at the time that this was only the prelude to a drama that would unfold anew ten and twenty years later when what Martin Buber had called the “unspeakable Jewish tragedy” would finally acquire a name.

Excerpted from In Hitler’s Munich: Jews, the Revolution, and the Rise of Nazism by Michael Brenner. Copyright © 2022 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

Michael Brenner is a German Jewish historian who researches and publishes on the history of Jews and Israel.