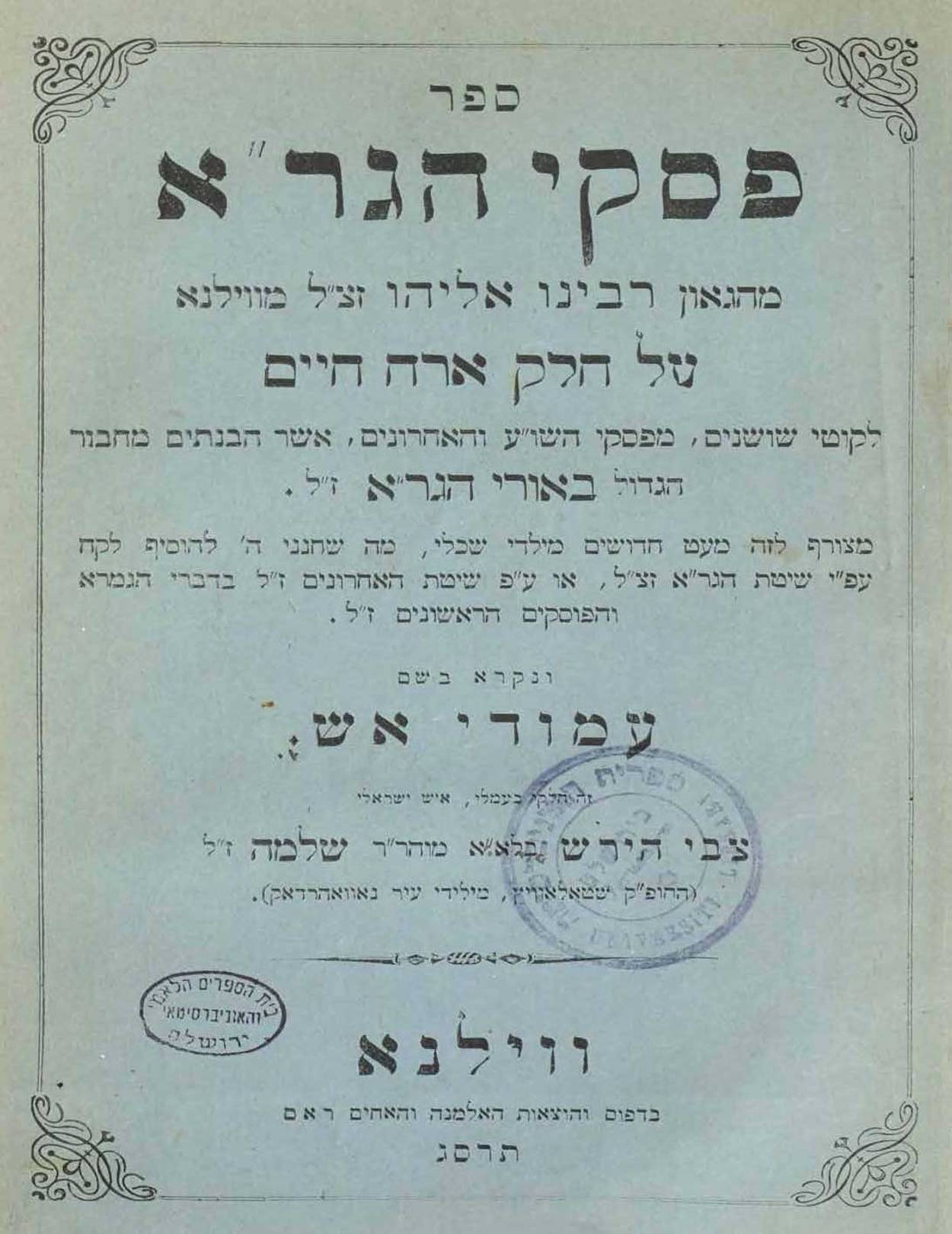

The Book

Piskei ha-Gra

By the Gaon, R. Eliyahu of Vilna

Choice selections from the rulings of Shulḥan ‘Arukh and the Aḥaronim, as I have understood them through the great work Be’urei ha-Gra.

Accompanying this are some of my own novel insights, whatever God has graciously enabled me to further understand from the Talmud and early decisors, based on the methodology of the Gra and of the Aḥaronim.

This is titled

‘Ammudei Esh.

This is the portion for which I must toil as a Jew,

Tzvi Hirsch, son of my master and father, our master and teacher Shlomo

(Residing in Stolovitch, raised in Novardok)

Published by the Widow and Brothers Romm

Vilna 1902-4

Rabbinic Approbations

When the learned, sharp, and esteemed rabbi, the honorable Torah scholar, our master and teacher Tzvi Hirsch, son of our master and teacher Shlomo, head of the rabbinic court in Gudleve, showed me his book Piskei ha-Gra, I looked favorably upon his efforts to publish it. I also saw some of his own novel insights on passages he deemed worthy of elucidation, which I fully support. May it be His will that he can succeed in this wonderful project and print it with God’s help. May God assist him in bringing merit to the masses, who ought to help him. I hereby pledge that I shall buy a copy, God-willing, when it comes off the press with the censor’s imprimatur, in accordance with the law of our lord the czar (may his glory be uplifted), and pay the price set for it.

Signing for the honor of the Torah and the commandments:

Monday, 24 Iyyar 5634, Kovno

Yitzḥak Elḥanan

The learned, sharp, and esteemed rabbi, our master and teacher Tzvi Hirsch, son of our master and teacher Shlomo, head of the rabbinical court of the holy community of Gudleve, showed me his book Piskei ha-Gra. It has explanations of a number of recondite passages of [the Gra’s] holy words, some of which I saw and found most agreeable. It is proper for the aforementioned rabbi to publish [the book] so that it sees the light of day. I, for my part, hereby pledge to buy a copy at full price, God-willing, when it comes off the press with the censor’s imprimatur. It is honorable and proper to assist him for the honor of the Gra, whose words are like sweet but difficult to obtain honey. We must certainly applaud whoever toils away at elucidating and organizing his halakhic rulings. May it be His will that he succeed in this wonderful project and print it, as is fitting. May the Omnipresent come to his aid.

The words of the undersigned:

Wednesday, 26 Iyyar 5634, Slabodka

Ya‘akov Eliyah, son of my master and father, our teacher Uriah ha-Levi

We have seen with our own eyes the precious work of the esteemed rabbi, light of the exile, famous for his Torah and pure fear [of God], the honorable Torah scholar, our master and teacher, Tzvi Hirsch, son of our master and teacher Shlomo, rabbi and religious judge in the holy community of Gudleve, who with the might of his pure hand has published refined and elucidated halakhic rulings from Be’urei ha-Gra on Oraḥ Ḥayyim, in which the Gra, reliant on his great mind, ruled in a number of places against the later decisors, the standard commentaries on Shulḥan ‘Arukh, and sometimes against the author of Shulḥan ‘Arukh [and Rema]. This in order that one can find a solid opinion on which to rely—the logical and Torah-true opinion of the holy Gra in his holy Be’urei ha-Gra—for many laws that have no halakhic bottom line in Shulḥan ‘Arukh and its commentaries. Since determining the Gra’s opinion from Be’urei ha-Gra requires a great deal of deep, continuous study of much of his holy book, we must applaud R. Tzvi Hirsch for exerting all his strength for Torah, and thereby shedding light on a number of mysteries through his intensive study. May God be with him to publish this precious work, and God forbid that anyone should infringe on his rights in any way. All the more so because aside from the obvious fact that the honorable rabbi toiled away to extract brief halakhic rulings from the Gra’s commentary, in which he had characteristically condensed many novel insights of halakhic consequence into the most concise allusions (who can truly fathom his profound opinion?), the honorable rabbi has also appended [his own] worthy novel insights and necessary elaborations of the Gra’s words (which he has called ‘Ammudei Esh). Therefore, anyone who holds the Gra’s teachings dear ought to assist him by purchasing his book. May the merit of our master stand by anyone who tries to clutch at the Gra’s coattails in Halakha, until we all merit hearing the words of the Ancient of Days, who will instruct us in justice from His holy heights.

Signing for the honor of the Torah and those who study it with love:

Wednesday, 19 Adar I 56(2)[3]5, Vilna

Yosef, son of our master and teacher Refa’el

Betzal’el, son of R. Yisra’el Moshe ha-Kohen

“Praiseworthy is the one who has arrived here with his learning in hand!” My friend, the famous rabbi, our master and teacher Tzvi Hirsch Lamport, head of the rabbinical court of Stolovitch, has shown us a draft of his Piskei ha-Gra on Shulḥan ‘Arukh—Yore De‘a. He already won renown for his [Piskei ha-Gra] on Oraḥ Ḥayyim over twenty years ago; leading scholars praised it and commended Tzvi, and this is a repeat performance. He has successfully gone the extra mile, adroitly navigating the sea of Talmud to understand the opinion of the pious and saintly genius Eliyahu, may his merit stand by all who learn and teach his teachings. I say the fruit is ready, so let’s eat! Whoever toils in Torah the Torah toils for him, and the honorable scholar has toiled away to prepare delicacies for the tables of the majestic rabbis. The meal is ready for Torah scholars, fit to be published for this generation! Let him receive reward, let his wellsprings spread outwards and his teachings be disseminated throughout the world. I hereby recognize and esteem him before everyone I know, in order to strengthen and support him in bringing his work to print. It is a mitzvah to support and assist him, and God forbid that anyone should infringe on his rights, according to the law of the Torah and of our master the czar. I shall purchase a copy at whatever price is set for it, and may it please God to happen soon.

Speaking for the honor of our holy Gaon:

Tuesday, 10th day of the ‘Omer, 5657, Mir

Eliyahu Dovid Rabinovitz Te’omim,

son of my master and father, our teacher Benjamin

In order to demonstrate that I have in fact read his words, I would like to append some of the many remarks that have come to mind. […]

I have many other things to note, but I do not have time at the moment.

May God help the honorable Torah scholar bring this project to fruition soon.

Wishing you well from the bottom of my heart,

Sincerely,

Eliyahu Dovid

The learned, sharp, and esteemed rabbi, our master and teacher Tzvi Hirsch, head of the rabbinical court of the holy community of Stolovitch, has already published Piskei ha-Gra on Shulḥan ‘Arukh—Oraḥ Ḥayyim, extracting pearls from the Torah of our great master the Gra, and the top Torah scholars of the generation have shown their approval. Now I see that he has done it again with Shulḥan ‘Arukh—Yore De‘a, and this repeat performance is as good as the original. He has also added fitting notes of his own to explain the words of our great master in a number of places. To praise this work would be superfluous, because its source is the Torah of the Gra. We are confident that our Jewish brethren will purchase them for their children and their children’s children and bring this blessing into their homes, to be suffused by the light of our great master’s Torah. It is a mitzvah to encourage and strengthen the author by lending him support and assistance, and it is prohibited to infringe on his rights. Let him be mentioned positively among those sitting and pondering God’s Torah.

These are the words of the undersigned:

Thursday, the 26th day of the ‘Omer, 5657

The holy community of Babraisk

Refa’el, son of our illustrious master and teacher, Leib Shapira

Comment by comment he delves into the profundity of the holy forefather, the Tanna of the academy of Elijah, desirous and yearning for the holy Torah of our great and saintly master, the Gra of Vilna, he being none other than my dear friend, the learned, sharp, and esteemed rabbi, the honorable Torah scholar, our master and teacher Tzvi Hirsch Lamport, head of the rabbinical court of the holy community of Stolovitch, whose book Piskei ha-Gra on Oraḥ Ḥayyim came out a long time ago, and whose book on Yore De‘a will soon appear in print. How wonderful is his lot! It is no small thing to discern in which direction our master’s opinion inclines halakhically, for his words appear like small stars in the eyes of flesh and blood, yet the entire world is positioned under a single star. For this reason, I wholeheartedly give my consent to print it, and may the merit of our master stand by him.

Sunday of the weekly portion of “May the Lord bless him,” 5659

Novardok

Yeḥiel Mikhl Halevi Epstein

With God’s help

I have seen two wonderful things, two compositions that come together harmoniously in purity and sanctity: Piskei ha-Gra on Shulḥan ‘Arukh—Yore De‘a and on Shulḥan ‘Arukh—Ḥoshen ha-Mishpat, shown to us by our friend, the great rabbi, our master and teacher Tzvi Hirsch Lamport, head of the rabbinical court of Stolovitch in Minsk governorate, who won renown many years ago on account of his [Piskei ha-Gra] on Shulḥan ‘Arukh—Oraḥ Ḥayyim. He showed us a draft for the portions of Yore De‘a and Ḥoshen ha-Mishpat, over which he has labored and toiled, combing the fields for the choicest flowers. He has neatly laid out for us, section by section, the opinions of our master, according to his great knowledge. God’s will is fulfilled through him, as the spirit of the laborer labors for Him, to grasp the mind of His saint and to decipher his characteristically scattered and ramified allusions and insights. This way, all who love [the Gra’s] Torah and gulp down his holy words, and even those not fortunate enough to own Be’urei ha-Gra, can hold the complete Torah of our master in their hands. For love of the holy, I attended to my manifold obligations and reviewed his compositions to the extent that time allowed, and I found the second and third to be similar to the first: he opens the halakhic door for us by throwing himself fully into it with his redoubled spirit. Given the foregoing, I hereby relate his praise to everyone I know, for he is worthy of support in order to publish [the books], with God’s help. We must applaud him for exerting all his strength for Torah. May the merit of our pious and holy master stand by whoever learns his teachings, and may all who lend support and assistance see happiness in this [world] and the next.

Writing and signing for the honor of the Torah:

Sunday of Be-Ha‘alotekha, 5660, Mir

Eliyahu Dovid Rabinovitz Te’omim, son of my master and father,

our master and teacher Benjamin, of Ponevezh

The learned, sharp, and esteemed rabbi, of vast learning and exceptional acuity, our master and teacher Tzvi Hirsch, son of our master and teacher Shlomo, head of the rabbinic court of the holy community of Stolovitch, won renown upon the publication of his wonderful work over thirty years ago. The work essentially reproduces all of the halakhic rulings of Shulḥan ‘Arukh—Oraḥ Ḥayyim in accordance with the halakhic decision and assent of our great pious master, the Gaon of Vilna, in Be’urei ha-Gra on Oraḥ Ḥayyim, wherever Shulḥan ‘Arukh brings two opinions and the expansive mind of this giant decided in favor of one of them. The aforementioned rabbi copied all of them in his composition and fittingly titled it Piskei ha-Gra. We owe a profound debt of gratitude to the honorable Torah scholar for this book, one that we cannot even begin to repay. To produce this work for us, the honorable author has undertaken an enormous project that combines art and wisdom, because in order to comprehend the words of the Gra, to truly fathom his opinion and his decision between halakhic opinions, based on proofs cited from the Talmud Bavli, the Talmud Yerushalmi, the Tosefta, and more, requires serious work, immense exertion, and an extra measure of wisdom and discernment. The honorable scholar and author sifted through it multiple times and produced the finest of the fine from Be’urei ha-Gra, his unadulterated and clear halakhic opinions, in order to enlighten the entire Jewish people about the Gra’s rulings. The book has already been well received by all the leading lights, who have roundly praised it. In fact, many, including those thirsting for God’s word and His Torah, have asked: Who could write such a book for the other three parts of Shulḥan ‘Arukh, in order to enlighten us about the Gra’s rulings found in Be’urei ha-Gra on Yore De‘a, Even ha-‘Ezer, and Ḥoshen ha-Mishpat, and especially on Yore De‘a, so critical for all rabbis providing practical halakhic instruction? How fitting it is, then, to show gratitude to the honorable scholar and author, who voluntarily shouldered this burden of extracting pearls and producing crystal-clear Halakha from Be’urei ha-Gra on the other three parts of Shulḥan ‘Arukh as well. He has fulfilled what the sages said: “the mitzvah is only attributed to the one who completes it.” Although I have not had time to review everything he has written on Yore De‘a and Ḥoshen ha-Mishpat, the little I have seen testifies that it is entirely good and arranged as clear Halakha, and that he has grasped the Gra’s intent in determining every one of his halakhic opinions. What was true of his first work holds true for the second. We must congratulate him for exerting all his strength for Torah. God’s will shall be done in bringing his project to fruition and publishing and disseminating this second composition speedily, in order to bring Gra’s rulings to the public. It is a great mitzvah, befitting every serious student of Torah, to purchase this book from him with good cheer when it is published with the censor’s imprimatur. Upon its printing, I, too, will purchase a copy from the author at the price set for it.

Such are the words of the writer for the honor of the Torah and its learners, signed:

Sunday night, 16 Elul 5660.

Shlomo, son of my master and father, our master and teacher,

Yisra’el Moshe ha-Kohen, religious judge of Vilna.

Bless the Lord

The words of our great master the Gra shine like stars with the radiance of the firmament. Like stars, they appear small, yet each one is a world unto itself. That is why so many top Torah scholars and leading rabbis have set their hearts to elucidating his writings on matters exoteric and esoteric, many of which have been printed and even more of which remain hidden and unpublished. Now my friend, the great rabbi, our master and teacher Tzvi Hirsch Lamport, is one of those toiling to understand his holy and pure halakhic opinion from his novel insights on the four parts of Shulḥan ‘Arukh. He has already printed [those] on Oraḥ Ḥayyim and Yore De‘a, and now intends to publish one on Ḥoshen ha-Mishpat. We applaud him for exerting all his strength for Torah. May the merit of our great master stand by him. It ought to be printed for this generation.

5 Marḥeshvan 5661, Novardok

Yehiel Mikhl ha-Levi Epstein

Dear readers!

Listen to me, pursuers of peace, seekers of the Torah. When you see my introduction to this work, which is long, do not be put off by it. Let me tell you that I did not merely fill space there; thanks to God, you will find Torah of halakhic consequence there. Do not give up in the middle: read it from beginning to end, and God-willing you will find the introduction pleasing, come to realize that it too is Torah, and mention my name fondly in connection with it.

With my blessing,

The author, Tzvi Hirsch Lamport

Author’s Introduction

In chapter four of tractate Avot (4.1), Ben Zoma has the maxim: “Who is wise? Whoever learns from everyone.” It seems to me that the explanation is as follows. The rabbis expound the verse, “For your dew is the dew of lights [and earthward you make the shades fall]” (Isa. 26:19) as follows: “Whoever uses the light of Torah, the Torah’s light sustains him[, and whoever does not use the light of Torah, the Torah’s light does not sustain him]” (Ketubot 111b).

The nature of the soul is like that of the body. Corporeal life depends on cardiac health, because the source of life is in the heart. It is first in line to receive the influx of this-worldly vitality, and it distributes its bounteous vitality to all of the body’s limbs in order of their proximity. The integrity of the entire body depends on the health of the heart, so as long as the heart’s heat has not ceased, there is hope for restoring the body’s health, and we do not consider it lost in its illness. But when the inborn moisture deep in the heart dries up and its heat ceases, then it is not long for this world, and it is futile to search for strategies to restore its health.

The rabbis famously said: “The tendons of the eyes are dependent upon the valves of the heart” (‘Avoda Zara 28b). Therefore, it can be determined whether someone is in mortal danger and near death using this test. If you pass a lit candle before their eyes and they sense the candlelight, we can conclude that the heart is still warm and that they are alive—because we believe that someone in extremis is for all purposes considered alive. But if their eyes are dark and they do not sense the light, we can conclude that the fount of their vitality has dried up, since the heat of their heart has ceased.

Such is the character of the soul, too. So long as it senses the divine light of the Torah and enjoys its illumination, we can be certain that one is living a Jewish life: the embers of God’s flame deep down in one’s heart are not yet extinguished, the divine spirit still blows between the furrows of the heart to heat it with the divine heat embedded within. But if, God forbid, someone forgoes light for darkness such that the divine light does not shine on them and they do not enjoy the divine light of the Torah, we can conclude that the heat of their heart has ceased and their divine spirit has gone cold. The divine flame implanted in the depths of the Jewish heart when our forefathers stood at Mount Sinai has been extinguished. That is why their eyes do not sense the pleasant light of the Torah—the divine light—which yearns to shine on the face of every Torah-observant Jew. We despair of their shelemut*, as they will only live the life of an animal, and not the spiritual life that defines the Jew. [*Translator’s note: The exact sense of the Hebrew shelemut here is unclear, as it is never defined. It seems more intellectual than moral, and perhaps refers to the breadth and depth of one’s Torah knowledge, perfect performance of the full complement of the Torah’s commandments, or self-realization given the compound nature of the Jewish individual detailed in the continuation. Given the ambiguity, I have left it in the original.]

This was what the rabbis intended in their carefully worded formulation in Ketubot: “‘For your dew is the dew of lights…’—whoever uses the light of Torah, the Torah’s light sustains him, and whoever does not [use the light of Torah, the Torah’s light does not sustain him].” It is as we have said: if someone does not use the light of Torah nor enjoy its illumination, we conclude that they are missing the proper inner harmony, that is, the divine force implanted in the Jewish heart, and that the spiritual vitality of the Jew is no more, such that in life he is called dead. As the saying goes, the wicked are called dead during their life, and live only the life of animals, the life of the flesh, which naturally decays and is obliterated. As it is written, “For you are dust [and to the dust shall you return]” (Gen. 3:19). Earlier [in Ketubot 111b], the rabbis similarly expounded the verse: “‘The dead live not[; the refa’im rise not]’ (Isa. 26:14)—one who becomes slack (marpeh) with words of Torah.” Since one has become slack with words of Torah, even while he is alive he is considered dead.

It is therefore incumbent upon every Jew worthy of the name Israel to acquire for themselves a goodly portion of the holy Torah, as we request daily: “grant us our portion of Your Torah,” or to be among those who constantly toil in Torah. Should a person not merit this, they ought to be a supporter of Torah [study], such that their portion will be united with those who do toil in Torah constantly. For this is the definition of life for the Jew, without which one is not called alive (as we have said), and as it is written: “for it is your life” (Deut. 32:47).

I further declare, regarding Torah-observant Jews who strive for shelemut, toil in Torah, and acquire a goodly portion of Torah knowledge, that is, they merit developing an unprecedented insight into some matter of halakhic consequence: How wonderful it would be if the greater and lesser scholars—each in accordance with their greatness, toil, and the intellect with which they have been endowed—would come together, and the greats would pay heed to those of lesser stature so that they could learn from one another. In this way, they would acquire the goodly portions of their colleagues, and their shelemut and their own portion would be magnified two- or even tenfold.

This is akin to many people who serve a sovereign, the eminent officials with their special ministries and the underlings with their lowly, menial labor. Each receives a salary commensurate with their station and labor; the higher officials, serving in a dignified post and taking care of important affairs, certainly receive from their master a portion ten, a hundred, or even a thousand times greater than that of the lower functionaries. And yet, if a lower official were to give a higher one the portion he received from his master, then the income of the latter would still increase one- or twofold—however much the salary of the latter is worth.

Such is the character of the holy Torah. It has the power and capacity to lavish its bounty upon every single person, the greater and the lesser receiving in accordance with their stature and efforts. But when the greater unites with the lesser, dialoguing with and learning from one another, the shelemut of the greater must certainly increase. About this the rabbis said: “The Torah is acquired only through fellowship.” The prophet likewise said: “For the lips of the priest preserve knowledge, and they shall seek Torah from his mouth” (Mal. 2:7). In other words, what is essential is that the teacher (the priest instructing the public) be fluent in the Torah in order to converse with everyone. He may not swell with pride and muse, “Who is as good a teacher as I am? What need have I of consulting with someone of lesser stature?” His lips must preserve the Torah in order to speak and consult with even lesser scholars on any issue that arises, because perhaps this matter falls to the portion of the lesser scholar. Who, asked Ben Zoma, can attain the proper shelemut and be called “wise”? “Whoever learns from everyone.” For thus did King David say: “From everyone—my teachers—did I learn, for your statutes are my discourse” (Ps. 119:99).

Given all the foregoing, I summoned the courage to go to print. I knew that the young would mock me: “Who is this scribbler inserting himself among the greatest masters? Too slow to keep up with the sages, he runs to compose novel insights.” I therefore ask of my fellow Jews who pursue truth and Torah to accept the truth from whomever may speak it, and to kindly consider what I have said. Before you I am but a lowly disciple, yet perhaps in some matters Heaven has allowed a young man like me to distinguish myself. Thank God, I have toiled a bit in Torah, and my lot has always been among the regulars of the study hall. I have suffered much hardship and penury. For nearly ten years have I borne the heavy burden of instruction, leading the Lord’s people according to the path of Torah and proper conduct, instructing them in the law. I have had no reprieve until this very day. I have been forced to move around from place to place, each stop along the way too meager to satisfy me and the nursing babes with me during this period of inflation, when expenses are great and any income disappears in an instant—may God show mercy in the days to come. Despite all this, I have maintained my daily regimen and not diverted myself from the study hall, spending my nights in deep study of Halakha to the best of my ability. Perhaps, then, you will find the portion allotted me pleasing, in the ruminations of my poor mind recorded in what I have titled ‘Ammudei Esh, and especially in my gleanings from the Gra’s exalted Be’urei ha-Gra, collecting the practical rulings in which he diverged from the opinion of the great Shulḥan ‘Arukh or the Aḥaronim, because everything he said was characteristically according to the truth of the Torah. But who am I to sing the praises of someone for whom silence would be more fitting praise? Public knowledge requires no affirmation. The man and his compact writings speak for themselves: they are of halakhic consequence and not mere theoretical analyses.

For a long time, I was confounded: Why has the fate of Gra’s expositions been so different from those of the Rishonim and Aḥaronim, from whose waters we draw knowledge and practice, the light of whose learning everyone enjoys? After their lengthy discussions, they would capture the innovative halakhic ramifications of their sweet pilpul in the form of brief rulings. Greater scholars would know these rulings and how they were derived through pilpul; lesser scholars would know the brief rulings, like the Piskei Tosafot for Tosafot and the Piskei ha-Rosh for Rosh. Some of the greatest Aḥaronim even followed this path, such as the author of Urim ve-Tummim, the author of Netivot, and the like. Yet this light, namely Be’urei ha-Gra, has been essentially hidden and sealed, this brilliant light wrapped in meager words. Few are they who drink from the waters of [the Gra’s] learning; few are they who use his light. His opinions and innovations are unknown. Maybe one in a thousand takes the time to scrutinize and delve into the Gra’s words, discovering between the lines delightful blossoms, the fruit of insight, and a cornucopia of delicacies from the Talmud Bavli, the Talmud Yerushalmi, and the greatest decisors of the Rishonim and Aḥaronim.

Did the Gra not want his teachings disseminated in synagogues and study halls, for which the rabbis say (Yevamot 96b-97a) King David prayed, in the verse: “Let me dwell in Your tent for worlds” (Ps. 61:5), and elsewhere? And if the Gra did not want us to rely on him for Halakha, which is why he wrote esoterically, so that his true intent could be discerned from his allusions only by the worthy, because a word to the wise is sufficient, then how could the author of Ḥayyei Adam and many Aḥaronim cite the unique rulings of the Gra? Who permitted them to reveal his secret, to publish words spoken in confidence? I therefore declare that since the Gra put pen to paper and inscribed them in a book, he intended them to be printed so that they would stand the test of time. He also would have wanted his teachings to be discussed by halakhists of authority in halakhic fora. Since he did not elaborate on his rulings, and none of the Torah giants of past generations merited this good [portion in Torah], perhaps Heaven has reserved this for me, it being the goodly portion for which I must labor. I have therefore gathered my strength and encouraged myself: “Go read these holy words and gather the Gra’s rulings. Work assiduously and the reward will come. Don’t stop until your work is done. God and the Gra’s merit will assist you, standing by you and by those who support and help you. Do not be abashed on account of those who scorn book-writers, because the bashful do not learn.”

For about two years have I labored over this, in painstaking study of every single word of the Gra. God assisted me in realizing my vision; as of now, I have collected all of his rulings on Oraḥ Ḥayyim. I now ask compassion of the rabbis and their disciples. Take home this blessing, these rulings of the Gra, and the merit of the Gra will stand by all of us, by all who adhere to the justness of his path, and by all who assist in disseminating his teachings. In so doing, it will be as if he were living amongst us again, like the statement of King David, “Let me dwell in Your tent for worlds,” and according to [the rabbis’] interpretation.

I ask of those always engaged in learning Torah, who seek the truth: should you find a mistake in my words, judge me favorably, because people are liable to err, like King David said, “Who can discern mistakes?” (Ps. 19:13). Additionally, I studied in conditions of great hardship and poverty, yet “learning requires a clear mind.” Judge everyone favorably. Perhaps a mistake can even prove beneficial to those engaged in careful study, for I have provided them an invitation to scrutiny. It is about such phenomena that [the rabbis] said: “If you had not lifted the potsherd for me, I would not have found the pearl underneath it.”

I thank God for the past, for bringing me to the finish line, and I offer a prayer for the future, that the merit of the Gra stand by me, and that God help me collect the Gra’s rulings on the other three parts of Shulḥan ‘Arukh, many of which I have already written. I offer this short prayer: May it be His will that my words be accepted by the Torah scholars of our time, as [the rabbis] said: “When R. Abba ascended [from Babylonia to the Land of Israel], he said: ‘May it be His will that I say something that will be accepted’” (Betza 38a).

But this seems bewildering. Was R. Abba seeking respect, such that they should accept his words even if not true to the Torah? Shouldn’t he have requested that he be directed to the truth of the Torah? This can be understood based on the beginning of tractate Shabbat in the Talmud Bavli (88b–89a): “When Moses ascended on high, the ministering angels said before the Holy One: ‘Master of the universe, You have had a treasure hidden away for 974 generations before the creation of the universe, and You intend to give it to flesh and blood? …’ The Holy One said to Moses: ‘Answer them.’ … [Moses said to them]: ‘Did you descend to Egypt? … Do you conduct business with one another? ….’” The commentaries ask: How could the angels have even thought to receive the Torah, since so many commandments are practical ones performed with limbs, such as tzitzit, phylacteries, and the like, and angels are immaterial, spiritual beings? How could they have observed the Torah’s commandments? Since we have mentioned this, let us say a little pilpul about it.

The author of Ketzot ha-Ḥoshen and Rabbi Akiva Eger asked about the following mishna: “‘Give this bill of divorce to my wife and this bill of manumission to my slave,’ one can retract the divorce but not the manumission” (Gittin 11b). The reason is that it is a benefit to the slave and we act in someone’s interest [even when] not in their presence. Since that is the case, the agent has acquired this bill of manumission on behalf of the slave, so the master cannot retract. But they asked: acting in someone’s interest is a form of agency, so it is through the agent’s acquisition on the slave’s behalf, namely his agency, that the slave is manumitted, which makes him an agent for a transgression, because “whoever frees [his slave …] violates a positive commandment”!* To resolve this conundrum, they engage in lengthy pilpul. I shall say my piece with God’s help. [*Translator’s note: Gittin 38b. The general principle is that there is no agency for a transgression, such that if one appoints an agent to steal something it does not create an agent-principal relationship, and the person actually doing the stealing is liable.]

Tosafot (Bava Metzi‘a 10a, s.v. tofes le-va‘al ḥov) are critical of Rashi’s explanation that if the creditor had appointed the seizer to be his agent then his seizure would be effective even when it is detrimental to others.* For in Ketubot 84b, it is clear that even if the creditor had appointed him his agent, his seizure would be ineffective. Shakh in Ḥoshen ha-Mishpat 105:1 defends Rashi, saying he meant that whenever he has been hired as an agent the seizure is effective, and Shakh rules that this is the Halakha. This is seemingly arbitrary. Why would a pro bono agent’s seizure not be effective but a hired agent’s would be? I saw that Korban Netan’el on Rosh in Gittin ad loc. gives a partial explanation of this Shakh in the name of his teacher. Since the agent receives pay, he himself has some interest in the act of agency, and since (miggo) he acts in his own interest, he can act in the interest of others as well. [*Translator’s note: The Talmudic passage on which both Rashi and Tosafot are commenting states that if a person seizes property for a creditor and it is detrimental to others (such as other creditors), it is ineffective. Rashi limits this to a case where the seizer is doing this of his own initiative, an agent doing the seizing would be effective.]

If so, a new principle emerges. According to Shakh, the hired agent’s seizure would be effective, which according to Korban Netan’el is because of miggo. It follows, then, that a hired agent could be an agent for a transgression. Because whence do we know that we apply miggo to seizure? It is based on an analogy with an agent for a transgression, as explained with respect to Rami bar Ḥama (see Bava Metzi‘a 8a). Therefore, here too, we apply miggo to an agent for a transgression, where a hired agent would be effective, as mentioned above.

Based on the above, there would be no difficulty with the aforementioned mishna in Gittin. [The question was] how the agent could acquire the bill of manumission on behalf of the slave, since acting in the interest of others works through agency and there is no agency for a transgression. Perhaps this case is one of a hired agent, and whenever one is hired the agency is effective even for a transgression, as explained above.

However, when one looks closely one sees that this is not the case. There is an opinion (Bava Metzi‘a 10a) that if someone lifts up a found object for their friend, the friend does not acquire it, because it is seizing for a creditor when it is detrimental to others. And yet, we rule that the Halakha is that the friend does acquire it, even though in general such seizure is not effective. Halakhists explain that lifting up a found object is better than seizing for a creditor because we apply miggo to the former. The same would be true (per Ḥoshen ha-Mishpat 105:2), though, when we can apply miggo to seizure, such as when the seizer is himself owed by the debtor and seizes the amount he is owed, but does so for his friend rather than for himself. However, if he seized more than his own obligation in a single swipe, both for himself and for his friend, Sema‘ and Shakh disagree. According to Sema‘, it is not effective, because miggo applies only when he can acquire it entirely for himself; the fact that he himself has some right to it is insufficient to acquire it for his friend (see Sema‘ 105:3). According to Shakh (105:2), his seizure is effective based on miggo. Given that Sema‘ opines that we do not apply miggo at all except where he could acquire it for himself if he wanted to, how can a hired agent be effective based on miggo with respect to seizure or a transgression like manumission? In these cases, one cannot say the agent could have acquired it entirely for himself. Consequently, according to Sema‘ the entire answer articulated above falls apart. On the other hand, when Shakh writes that a hired agent’s seizure is effective and that he can be an agent for transgression (105:1), he is being consistent, because he believes miggo applies to a hired agent (105:2), in line with the reasoning of Korban Netan’el above.

I think we can adduce proof from the Talmud (Bava Kamma 51a) to Sema‘’s opinion that a hired agent is ineffective for seizure. [The Talmud] raises a question: “‘A pit owned by two partners’—what is the case? […] If they both appointed an agent, saying ‘Dig us [a pit]’ there is no agency for a transgression.” According to Shakh, if a hired agent’s seizure is effective based on miggo, like the idea of Korban Netan’el, it should also work for a transgression, as proved above. But then why doesn’t the Talmud limit the case to where both partners hired him as an agent! It must be that Shakh is incorrect.

Let us return now to the passage from tractate Shabbat discussed above. R. Yonatan [Eybeschutz] in Ye‘arot Devash wrote that the angels were in an uproar over the giving of the Torah because they wanted to know why they were not appointed agents for giving us the Torah. Their claim can be illustrated by a parable. If a great king wants to bestow a gift upon someone he likes, and the gift is not so valuable or precious, then the king magnifies its importance to the recipient by handing it over personally. The very fact that the king gives it himself makes the gift important. But if the gift itself is valuable and precious, then there is no need for the king himself to give it, and he can send one of his servants to give it to the recipient. Even so, the recipient will deem it important given its high value. The angels contended: If the Torah were not so valuable or precious and You had wanted to magnify its important to the Jewish people, you would have needed to give it Yourself. But “You have had a treasure hidden away … and You intend to give it to flesh and blood?“ The emphasis is on the “You,” as in You Yourself. Instead, send it in our hands! This is their statement: “that you should give Your majesty ‘al ha-shamayim” (Ps. 8:2), that is, “via the heavenly beings (‘al yedei ha-shamaymiyyim).”

The words of this sage are beautiful and sweet, but if correct they pose a great difficulty. How are we to understand Moses’s response: “Did you descend to Egypt? ...” What kind of response is this if they weren’t accepting it for themselves but only intending to be agents? See R. Yonatan’s forced interpretation of the Talmud there. But based on what we said above this can be resolved nicely. The Talmud says about Mount Sinai, “Why is it called Sinai? Hatred (sin’a) descended from it to the nations of the world” (Shabbat 89a). And the same is true of Mount Horeb, from which destruction (ḥorbah) descended upon the nations of the world. Rashi ad loc. explains that it is because they did not accept the Torah. In that case, prior to the acceptance of the Torah by the Jewish people, it was like a found object resting in an ownerless property; whoever wanted to take it could have done so, as it is written: “God comes from Teiman, the Holy One from Mount Paran” (Hab. 3:3), and [the rabbis’] famous exposition of it. It was we the Jewish nation who acquired such a precious find, so the angels who wanted to act in our interest and acquire the Torah for us were exactly like someone who lifts up any old found object for his friend, concerning which there is an opinion in the Talmud that his friend does not acquire it because it is seizure for a creditor when it is detrimental to others. For us, someone lifting up a found object is better than someone seizing for a creditor because we apply miggo, since they could acquire it for themselves. The angels wanted to be agents in the giving of the Torah and to acquire it from the Holy One on our behalf, so they were exactly like the one seizing, but miggo can’t apply to them. The angels, though, were of Shakh’s opinion that a hired agent’s seizure is effective, because so long as they have an interest in it, it is as if they could have acquired it. As such, if they could be appointed agents for the giving of the Torah, they would definitely receive reward from God befitting their stature, for the Holy One does not withhold reward from any creature. Therefore, they contended before God that they should be agents. Moses, however, responded with the opinion of Sema‘, that miggo only applies when one can acquire it for oneself if one wishes. For that reason, Moses responded: “Did you descend to Egypt? ... Do you conduct business with one another? As such, you have no miggo, so your agency would not be effective here at all.” It would be exactly like seizing for a creditor when it is detrimental to others, as explained above.

Allow me to explain the rabbinic dictum in Shabbat in another fashion, one that is homiletical yet faithful to a simple reading of the text. It is self-evident that there is a resemblance between every actor and action, creator and creation. The angels are spiritual beings, so their action, like their constitution, is spiritual. All of their labor is conceptual, that is to say spiritual, in that they use their intellects to plumb the depths of the Torah and fully clarify the Halakha, deciding whether something is pure or impure, prohibited or permitted. As we find: “There was a debate in the heavenly academy. If the baheret preceded a white hair [one is ritually impure; if the white hair preceded the baheret, one is ritually pure]. In a case of doubt, the Holy One declares ‘pure’ and the entire heavenly academy says ‘impure’” (Bava Metzi‘a 86a). They also cogitate the intelligibles and apprehend the divine substance, His existence, to the extent possible, each one according to their level. As we say: “His ministers ask one another: ‘Where is the place of His glory?’”

Every mineral, plant, and animal is material, and such is any activity involving them: they are made into houses and structures for shelter and hiding, they are eaten for sustenance, they are used for transportation. All of these are material actions, just as they themselves are material essences. Now let us consider the human genus of the Jew, whose essence is composite: his body is material like the rest of the earthly existents, yet his soul is a rarefied spiritual essence, like one of the supernal separate [intellects]. It is necessarily the case, then, that his actions are dual: the material act resembles the essence of the body, and the spiritual act resembles the essence of the pure soul. We find that the actions of our holy Torah align with these essences of man: the commandments, such as tzitzit, phylacteries, and the like, are performed by the limbs and pertain to the material essence of the body; study of the holy Torah, which involves using the intellect to analyze and fully clarify the Halakha—in fact the primary goal of such study—in order to decide whether something or someone is pure or impure, prohibited or permitted, innocent or guilty, is a spiritual act.

Our holy Torah also obligates every Torah-observant Jew to use their intellect to investigate and apprehend God’s existence to the extent their intellect allows. As it is written: “Hear, Israel, the Lord [is our God, the Lord is one]” (Deut. 6:4), and “hear” refers to listening with the heart, as it is written: “You have given your servants an attentive heart” (1 Kgs. 3:9). Likewise, King David said to his son Solomon: “Know the God of your father […]” (1 Chr. 28:9). Ḥovot ha-Levavot contains an extensive discussion of this matter. As the prophet said: “One should pride oneself only on intellectual apprehension of Me” (Jer. 9:23).

All of these are commandments of the intellect carried out through analysis and cogitation, spiritual acts pertaining to the essence of the soul, which is spiritual. Therefore, the angelic argument might have went like this: “Master of the universe, why do You invite jealousy within Creation by giving to flesh and blood all the acts of the Torah, both the spiritual study and the material commandments? Master of the universe, divide it up and remove jealousy: grant us the spiritual act of [Torah] study, using the intellect to fully clarify the Halakha, because such spiritual action is pertinent to us as well, and give the material commandments to the Jewish people, since they pertain to flesh and blood.” If the Torah were to be divided in half, per the angels’ plea, then the actions we would perform and the path we would follow would not be depend, as it does today, on the accord of the human intellect; according to the rabbis in Midrash Rabba, the Holy One tells the angels: “I and you will go to the high court [down below].” Instead, it would depend on the accord of the supernal intellects, and they would be the ones to clarify the Halakha—rendering impure or pure, prohibited or permitted—and to inform us the path to take and what to do by means of a prophet or heavenly voice from on high. This was the argument of the angels.

Nevertheless, Moses’s answer, being based on the holy Torah, won out. The Talmud and codes clearly state that two brothers or partners who wish to divide their inheritance or a purchase may do so as long as [the item] will retain its original function. If it won’t, neither may force the other to divide it; instead, the law is “you set a price or I set a price,” even for separate items. But if both need each item it is like something indivisible, and neither can force the other to divide it, but “you set a price or I set a price” can be said about both of them (see Bava Batra 13a-b and Ḥoshen ha-Mishpat 171, regarding two maidservants, one of whom knows how to spin and weave and one of whom knows how to bake and cook).

In addition, the philosophers have defined something as alive so long as it fulfills its particular function. Any vessel that is whole and usable is also termed “alive” so long as it can be used in its particular manner; when it breaks and is rendered unusable, it is called “dead”—as the rabbis said about vessels: “their breakage is their death.” The same applies to man. So long as he strives for shelemut and does what he was created to do, he is called alive, but when, God forbid, he distances himself from shelemut and does not do what is incumbent upon him, he is not called alive, he is called dead even in life.

Therefore, if the Jew performs the dual activity of study and performance of the commandments, then he is called alive, but if some aspect of these activities incumbent upon him is lacking, then he cannot be called alive. The performance of the commandments sustains the material part, as it is written: “These are the commandments which man must perform and through which he lives”; the activity of study sustains the spiritual part. If we were to lack the learning component, we would only be living a material life, that is, an animal life. About this did the rabbis say: “the wicked are called dead during their life,” as mentioned above. It was concerning this that the rabbis said in Ketubot above: “Whoever uses the light of Torah …,” meaning that whoever does not use the light of Torah is called dead during their life. As such, both parts of the Torah are essential for us, the study and the practice.

This is what Moses responded to [the angels]. The Torah cannot be divided because we need both components. The only applicable rule is “you set a price or I set a price,” which was his intent in saying: “Did you descend to Egypt? ... Do you conduct business with one another?” By rights the Torah is ours, both the study and the practice. The Holy One affirmed his response. As such, our practice is guided by the accord of our intellects, per the human intellect’s understanding of the words of the holy Torah. Anything novel produced by someone who learns the holy Torah unceasingly, which is accepted in the study hall by the rabbis, is the truth of the Torah as God wills it. This is what R. Abba was praying for, that he say something that would be accepted, because on acceptance it becomes the truth of the Torah.

In that vein, I pour out my words before God that He allow me to merit saying something acceptable in the eyes of contemporary scholars, and then I shall trust in the Lord that he has granted me the truth of the Torah.

I have called this work of mine Piskei ha-Gra for it is as it sounds, the rulings of the Gra as I have understood his holy words. The product of my own poor intellect I have called ‘Ammudei Esh, because this name includes the name of my mother and father, may they rest in peace. May the merit of the Gra stand by me and by all those who have supported me in publishing this book, so that the Torah does not depart our mouths and those of our children and grandchildren, and so that God open our eyes to His Torah and save us from error. “Open my eyes so that I may see wonders from Your Torah.”

5635, Gudleve

The words of one who speaks for the honor of the Torah:

Tzvi Hirsch, son of my master and father, Shlomo of blessed memory

Translated from the Hebrew by Daniel Tabak.