The Jewish VD Detective Who Exposed the Infamous Tuskegee Experiment

Black History Month: How whistleblower Peter Buxtun came to recognize a great injustice, and act on it

Peter Buxtun was just returning with a sandwich to the lunchroom of the Public Health Service clinic in San Francisco’s Castro district when he overheard colleagues discussing an unusual incident that would trigger a long-lasting moral crusade and gain Buxtun a place in medical history. A Czech-born Jew from Oregon’s Willamette Valley, Buxtun would be the lone figure to recognize a great injustice, and persevere year after year in prodding his more credentialed superiors to end the most notorious research experiment in American history–the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

His singular journey would begin innocently enough during his lunch break in the mid-1960s. “I’m seated in this dinky coffee room,” Buxtun recently recounted to me, “and I hear several colleagues talking about an ill, insane man who was taken by his family to see a doctor outside of Tuskegee, Alabama. The doctor determined the man had syphilis and gave him a shot of penicillin. To everyone’s shock, however, the doctor was soon called on the carpet by physicians for the Communicable Disease Center (known today as the Centers for Disease Control) and reprimanded. They said he had ‘ruined their study’ and ‘jogged their statistics.’”

Buxtun was dumbfounded. Here he was a CDC outreach worker—a contact tracer in today’s parlance—assigned to find gay and straight men with venereal diseases and ensure that they received treatment. He was shocked to learn that CDC officials were berating physicians in Alabama for giving ill men the medicine they needed. “I thought it very bizarre,” Buxtun recalled. “I didn’t understand what they were doing. Why was this outside doctor jumped on by Tuskegee physicians? It made no sense.”

Buxtun peppered his colleagues with questions, but few had answers. The next day Buxtun phoned CDC headquarters and asked what was going on in Tuskegee? “They told me they had files on it and I said send me everything you have. I told them I’d like to know what’s going on.” In a matter of days, he received “a fat envelope filled with information about round-ups” involving hundreds of locals—unschooled Black sharecroppers in Macon County, Alabama, who had syphilis. Surprisingly, they weren’t being treated.

“I was aghast,” said Buxtun. “What the hell do they think they’re doing? I’m in San Francisco working hard to fight the spread of syphilis and they’re not treating people? My job was to track down those spreading syphilis and gonorrhea and get them a shot of penicillin. I was going into terrible neighborhoods, making sure carriers got medication, and in Tuskegee they’re not even treating men they know are sick. I couldn’t understand it.”

Syphilis was recognized throughout the ages as an embarrassing and deadly scourge. Up until WWII the best the medical community could come up with to fight the disease was a less than effective arsenic concoction. But by the end of the war penicillin had proved itself a miracle cure for myriad sexually transmitted diseases—syphilis included. Withholding such inexpensive medication from those who needed it was mind-boggling.

Perplexed, Buxtun talked with his colleagues, visited libraries, and began to do a full-court press regarding the strange goings-on in rural Alabama. The specter of poor Black men being used as cheap and available test subjects by government doctors in what looked like a large nontreatment syphilis study angered him. He started to educate himself on the history of unethical research and even began to “look up the German experiments at Dachau and Auschwitz.”

His coworkers, however, became increasingly agitated by his fixation on the mysterious PHS study, and cautioned him to cool it. Why was he so preoccupied with a study involving 400 Black men in Alabama? His persistence, they warned him, was guaranteed to cause problems. “My boss said, if you make a big fuss, you’ll be fired,” Buxtun told me. “Colleagues said don’t get me involved. What do you think you’re doing? Some had wives and children and obviously nervous about losing their jobs. They told me, ‘Don’t mention my name in whatever you’re doing. I don’t want to get fired.’”

Disregarding their advice, Buxtun—who had only been on the job a few months after serving as a combat medic in Vietnam—decided to fire off a letter to his PHS superiors. In it he compared the experiment in the backwoods of Alabama to the infamous Nazi concentration camp experiments that had chilled the world a couple decades earlier. Such an allegation did not go unnoticed; Buxtun was ordered to report to Atlanta immediately.

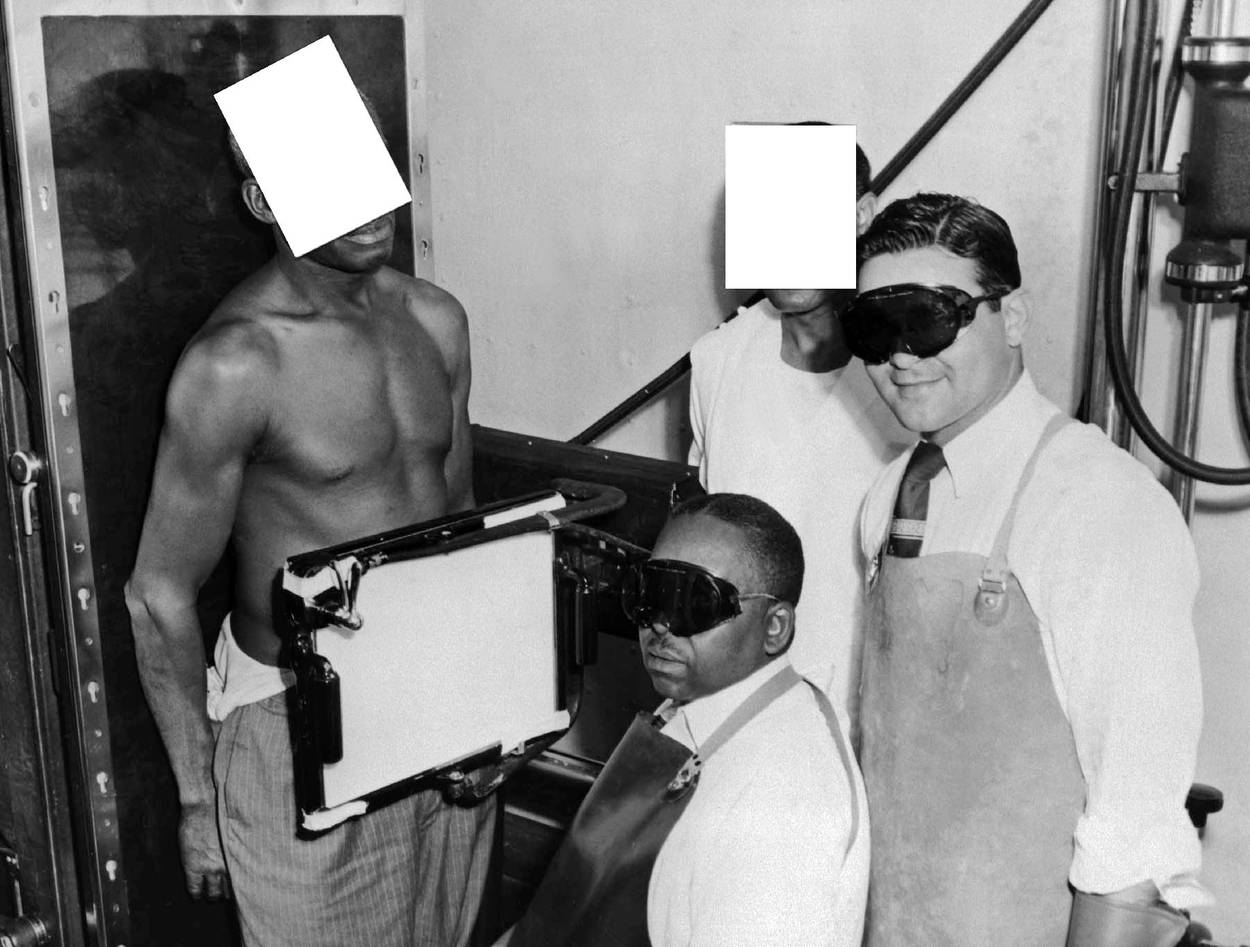

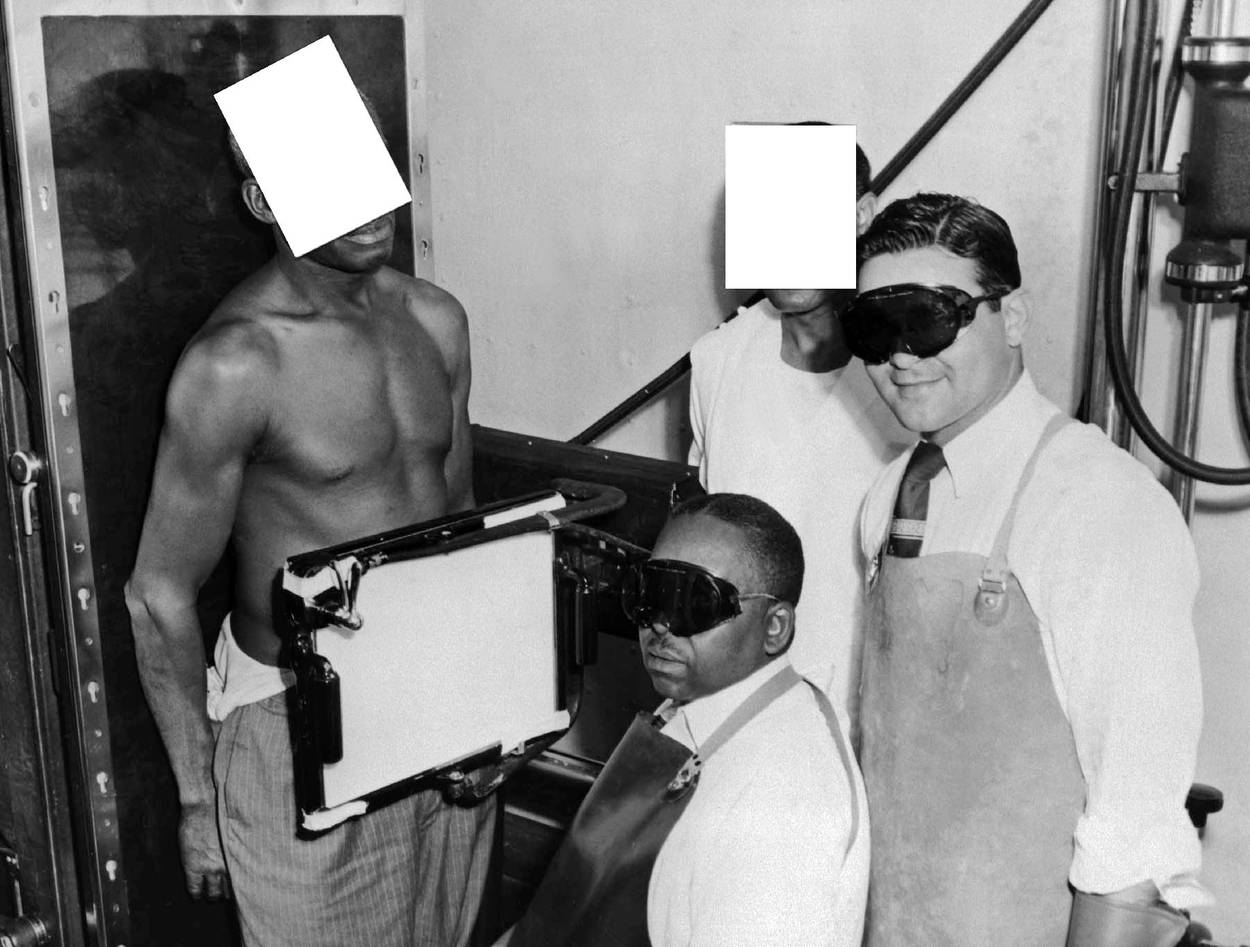

He was quickly disabused of his naïve notion that a rational discussion of the matter would result in the termination of the Macon County research project, and the long overdue treatment of Black syphilitics. “I was escorted to a downstairs meeting room and told to sit at the far end of a large conference table,” Buxtun recalled. There were several high-ranking CDC and PHS officials glaring at him including Dr. William Brown, the head of the Venereal Disease Division. His real nemesis, however, would prove to be Dr. John Cutler, a longtime VD official and a staunch defender of venereal disease research that routinely incorporated vulnerable test subjects, both in the United States and abroad.

“Cutler was exercised,” recalled Buxtun of the embarrassing event. “It was like his pants were on fire. He looks at me sternly and says, ‘Now see here young man, we’re getting a lot of good information from this study,’ and he starts lecturing me and reading from various reports as if the data is worth the lives of these Black men.” From the very first, Buxtun considered Cutler a “lying bastard.” The passage of years has not altered his “low opinion” of the man.

Most in the room that day no doubt thought they were done with the meddlesome VD researcher from San Francisco. But Buxtun wasn’t your average social crusader. His capacity for principled combat over many years would prove nothing short of extraordinary. “I didn’t dedicate my life to catch the bad guys, but it just irked me what was going on down there,” he remembered. “What rotten bastards they were.”

Though heroic by any measure, Peter Buxtun and his crusade remain obscure; even most historians and bioethicists are unfamiliar with his name. If readers were to imagine a suitable profile for such a singular social crusader, they’d probably picture Buxtun as a Berkeley grad, staunch Bernie Sanders supporter, and memberships in the ACLU and Greenpeace. But they’d be wrong.

An arch-conservative and proud Oregon Duck, Buxtun is a lifelong Republican, strong NRA supporter (the owner of several dozen guns), and a collector of medieval weaponry. But regardless of his political persuasion, organizational affiliations, and hobbies, Buxtun learned at an early age to consider the lives of poor, Black sharecroppers beyond what they were thought of by the medical establishment: as autopsy material. He did not need a popular movement or newspaper headlines to tell him what to do. Buxtun saw a wrong perpetrated by powerful forces and spent years trying to right it. Without his courage and perseverance there is no telling how much longer the ethically toxic Tuskegee Syphilis Study would have continued.

Buxtun’s animus toward the men behind the already several-decade-old Alabama syphilis study was probably rooted in his own family’s travails in Europe. Peter’s father was a Jewish industrialist and his mother an Austrian-Catholic housewife. His father had served in the army during the First World War and knew he was lucky to survive the carnage, and with the rapid rise of Hitler a dark omen for all of the Jewish faith, the Buxtun family knew they had to flee. “I clearly remember my father telling people to get out,” said Buxtun. “He told them it was important they get out of Czechoslovakia as quickly as possible.”

Suspicious of his plans and loyalty, the Czech government kept track of Peter’s father and kept a close watch on his textile plant. Unbeknownst to them, Mr. Buxtun had been planning his family’s escape. While he kept his normal schedule and stayed busy at his Prague linen factory, in early 1939 he had two automobiles secretly transport his wife, child, and several other relatives out of the country. They eventually fled to Brussels where they waited for several weeks until Mr. Buxtun was able to join them. Once that dangerous feat was accomplished, they crossed the channel to London and then boarded the New Amsterdam, a Dutch vessel, for the long voyage to America.

They were in New York only a short time before the Buxtun family was off again, this time to the far Northwest and that stretch of Oregon real estate between Corvallis and Eugene. They settled on a ranch and the young Jewish immigrant grew up an outdoorsman surrounded by animals, vast acreage, and a strong independent streak. He was determined to end the little known “study of untreated syphilis in the male negro” that had been underway for an astonishing 35 years.

In a November 1968 letter to the CDC’s Dr. William Brown, Buxtun reasserted his “grave moral doubts about the propriety of this study,” and fervent opposition to its continuation. He went on to point out, “1) The group is 100% negro. This in itself is political dynamite” and substantiates allegations “that negroes have long been used for medical experiments and teaching cases in emergency wards of county hospitals. 2) The group is not composed of volunteers with social motives. They are largely uneducated, unsophisticated, and quite ignorant of the effects of untreated syphilis. 3) Today it would be morally unethical to begin a study” with such a disadvantaged population. Buxtun concluded his letter with the request, “I earnestly hope that you will inform me that the study group has been, or soon will be, treated.”

Buxtun would once again be disappointed. Three months later in February 1969, Dr. Brown would write back that “a committee of professionals from outside the National Communicable Disease Center” had been assembled to consider “treating the remaining persons in the study group” and “after an examination of the data and a very lengthy discussion regarding treatment, our committee of highly competent professionals did not agree nor recommend that the study group be treated.”

Buxtun was appalled and frustrated, but he had no intention of giving up. Into the 1970s he continued to communicate his concerns with anyone who would listen, and generally make a nuisance of himself. Though he had left the PHS, entered law school, and developed new interests and pursuits, ending the unethical medical treatment of Black sharecroppers in Alabama remained a cause he wouldn’t abandon.

As Buxtun pursued his crusade, I, too, witnessed the misuse of African Americans—thousands of them—as raw material for experimentation. Entering the Philadelphia Prison System in 1971 as the director of a literacy program, I was stunned to see scores and scores of Black inmates adorned with adhesive tape and medical bandages. Not the result of a cellblock knife fight or gang war in the exercise yard, the men were part of an industrial-size medical research program conducted by Dr. Albert M. Kligman, a renowned University of Pennsylvania dermatologist. Inmates—desperate for money—were paid a dollar a day to test a wide array of detergents, hair dyes, athlete’s foot medication, diet drinks, and assorted other concoctions and products.

Willing to contract with anyone with a protocol and the money to fund a clinical trial, Kligman often boasted of his access to “acres of skin” and feeling like a “farmer overlooking a fertile field.” He’d become one of the nation’s largest phase I drug study contractors, highly quotable, and enormously wealthy. His endless stable of “test material” was also used for considerably more dangerous experiments that tested radioactive isotopes, dioxin, and chemical warfare agents on prisoners. The inmates were given little information and the staff knew better than to ask questions. An urban prison system had evolved into a supermarket of clinical exploitation and corporate moneymaking, but few took notice.

My initial questions about the prison tests to correctional officers and social workers were congenially answered. However, when I inquired about the short- and long-term effects of the tests, the products they were testing, the companies involved, and the assurances the inmate test subjects were given that no harm would come to them, I was advised to stop asking questions and forget what I had seen. If I continued my quest for information, I’d be escorted out of the jail.

Though the prison experiments in Philadelphia were unknown to the general public at the time, it would not be long before the shocking news of hundreds of men with syphilis going untreated for decades exploded across the front pages of American newspapers. Buxtun had finally hit pay dirt; he convinced a friend, a journalist named Edith Lederer, to look at some documents he had collected about a 40-year-old government experiment involving African Americans that was designed to end at autopsy. She couldn’t believe what she was reading. Her boss at the Associated Press assigned another reporter to write the story.

In June 1972, The New York Times and every other newspaper in the country informed readers of the most unethical piece of medical research in American history. Like the shot heard around the world, the revelations sparked a reassessment of clinical trials, especially those using vulnerable populations like the mentally ill, intellectually disabled, hospital patients, and prisoners. Human research initiatives around the country were shuttered, including Dr. Kligman’s prison experiments. Thousands of human beings who were made sick by unethical doctors and researchers can thank Peter Buxton, whether or not they or their families know his name.

Allen M. Hornblum is the author of eight books, including Acres of Skin, Sentenced to Science, and Against Their Will (with Judy Newman and Greg Dober) concerning the history of using vulnerable populations as subjects for medical research. His latest book, The Klondike Bake-Oven Deaths, will be published in February 2021.