Rav Karo and the Holy City of Safed in the Context of Ottoman Law and Sufi Practice

The rabbi’s time in the city shaped his vision of Jewish law as a channel to salvation

Rabbi Joseph Karo was first and foremost an impressive Talmudic scholar, unique even among the impressive group of rabbis and halakhic arbiters of Safed and the Sephardic Diaspora in the Eastern Mediterranean. His codes of law contributed to the halakhic renaissance of Sephardi scholarship in the sixteenth and (partially) seventeenth centuries. But he was not a regular scholar, as he combined an active and intense visionary and ecstatic life with his arduous and unceasing study of the immense “ocean” of Talmudic and post-Talmudic literature (Yam ha-Talmud).

There were certainly precedents for scholars combining sober Talmudic dialectics with enthusiastic mystical life and experiences, especially in the Sephardi tradition prior to the general expulsion. Yet none of them weaved these two domains—which nowadays seem so estranged to us “moderns”—so deeply one with the other, inserted typically Kabbalistic sources into the literature of Talmudic rulings (Sifrut Pesiqah), and enabled each domain to nourish the other, as did R. Karo.

He could not have borrowed such a model from the place of origin where his family and forefathers lived for centuries—Catholic Spain, or Christian Europe in general. No significant model for the fusion of juridical and mystical activities in the same person can be found in Church institutions (Canon Law), nor somewhat later in university law faculties (Ius civile), let alone any individual with as impressive a stature as R. Karo. Not surprisingly, looking at his neighbors next door in the Ottoman Empire, during his early life in Rumelia, and later as a scholar in Safed within the Bilad a-Sham area, he could certainly observe impressive scholars of the Muslim Shariʽa who were at the same time important and venerable Sufi masters.

Yet Karo’s response to the Islamicate and Ottoman space where he lived his entire life (excepting his years as a small child just before the expulsion) went much deeper. The vision that he had of himself, his life course, and the codification project resonated with what he saw around him. Like other important Sufis of the early modern period in the Ottoman Empire—either in the core lands or in the Arabic territories—he composed a mystical diary of immense measures, the Magid Meisharim. This was all unheard of in the Jewish context—both the autobiographical writing and the exposure of inner life as an important component of the via mystica. Although the Magid Meisharim at our disposal is much shorter and intensely edited, it is a completely unique artifact of its kind in Jewish tradition as a whole, and certainly in the rabbinical milieu.

The work follows R. Karo in his daily life, his relationship with his family, intimate moments with his wives, corporeal habits, sleep and waking, or personal and “professional” aspirations. His emotions and moods of self-criticism are a recurring theme throughout the diary. Yet the text is far from being a documentation of a personal life for its own sake. It revolves around meetings with a divine agent, named the Magid, Shekhinah, Mother (or better Rebuking Mother), Matronita, or Mishnah. The interaction is often stern and demanding on the part of the Magid, yet there are soft moments of proximity and even an erotic flavor of hugging and kissing. In some exceptional moments, Karo is elevated to high spheres in the divine world. The various entries in the diary present a journey not only of revelation of Torah secrets and various aspects of Jewish heritage and life but no less so an intensifying glorification of R. Karo himself.

An alternative mode of reading Magid Meisharim, and a constant theme in this diary, is the fundamental contact between R. Karo and imminent past scholars, the fountains of Talmudic scholarship. Karo is elevated to the Divine Yeshiva, where all the great names of Talmudic erudition of past generations face one another in regular and continuous study, as conducted in his contemporary world. There he was hailed and heralded by an angelic voice, and his exceptional erudition and talent were recognized by past scholars, from the Mishnah through the seventeenth-century sages. Past and present blend into one continuum of Jewish erudition, and all the scholars are searching for Talmudic truth and rabbinical consensus. The intimate interface between arduous Talmudic labor and grand mystical vision was masterfully described by Maoz Kahana:

The highlight of amassing and organizing [Talmudic] knowledge is, in fact, a moment of unification of God, the exhilarating moment in which the internal harmony between various halakhic traditions of the legal culture is revealed to the industrious composer. This exhilarating moment—constructing the Holy Temple by letters of the law—is identical and concludes the utopian methodology for exhausting the legal books, as expressed by R. Joseph Karo in his preface to Beit Yosef […] In his world, of a librarian, bibliographer and omniscient Halakhist, a cosmic unification of God is possible by means of a methodology of utopian-sober and daily writing, to which he aspired and materialized by writing Beit Yosef along dozens of years, by the unique ruling method that he set for it. In this sense, no less significant than inserting the Zohar to Beit Yosef, one should consider the Beit Yosef and Shulchan ‘Arukh as the utopian-legalistic materialization of total-knowledge methodology that the Zoharic-cosmogonic perspective furnished one of its bases, and actively participated in its self-construction [of total knowledge]. The diligent halakhic sage seen in the prism is a kind of creative and active Kabbalist. The law canon would be completed only after years of arduous work, yet the godly unification—this momentary tabernacle—is the daily highlight of writing each and every item of the law, when all the various sources integrate into an effective synthesis, explaining and illuminating one another. The Holy Temple is constructed by letters and words, words-courses of the Divine-total law, joining one harmony and construct an entire universe. A universe saturated with Law.

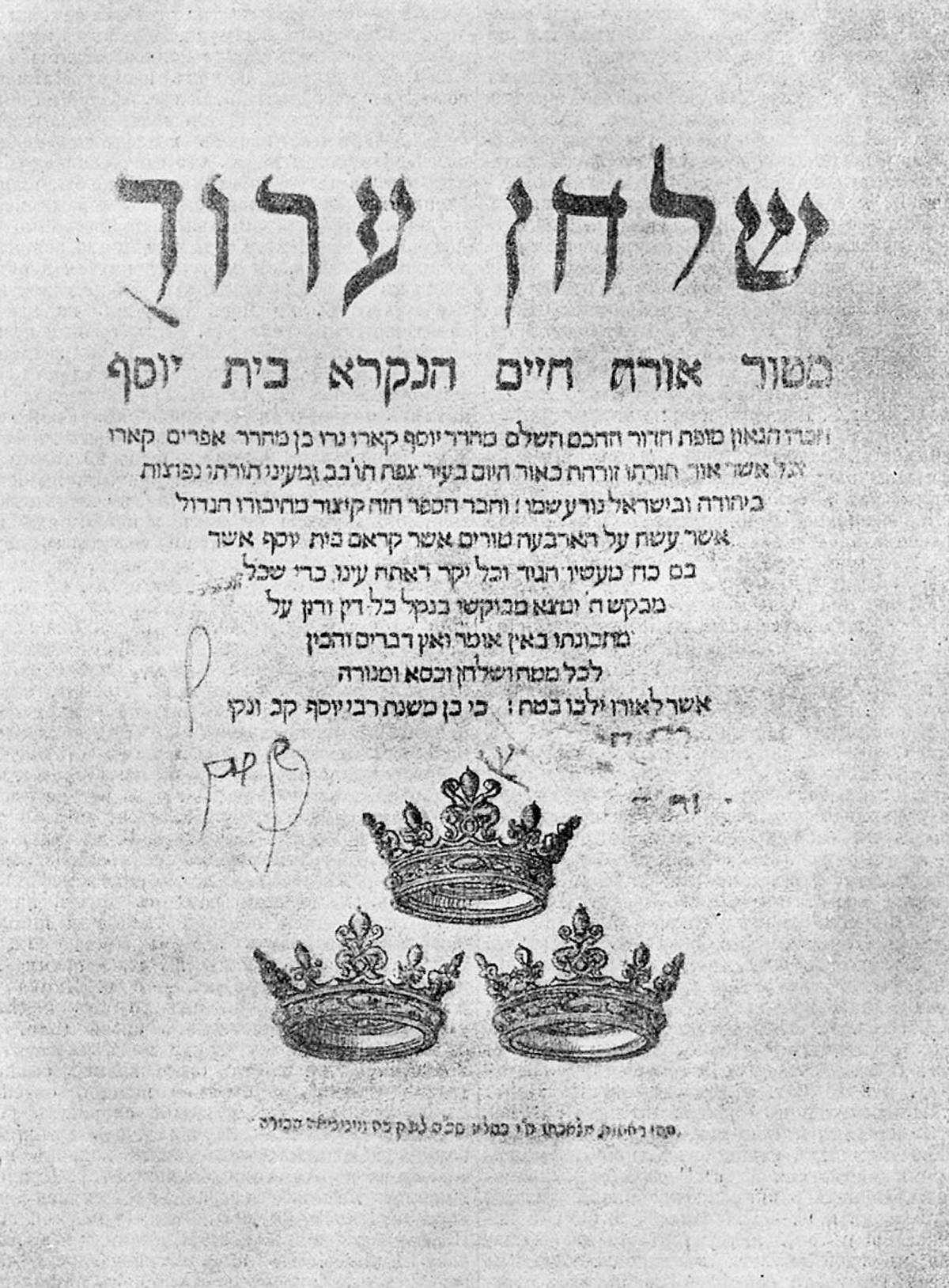

As much as R. Karo was no ordinary Talmudic scholar, so were his double codes of law no regular halakhic corpus. In at least two encounters with the Magid, Karo receives a promise that he will live to complete his codes, and is even provided with their exact titles: Beit Yosef and Shulchan ‘Arukh. The plan behind this immense corpus was vividly exposed in his important preface to Beit Yosef, and to a lesser extent to Shulchan ‘Arukh. Its goal was to foster unity and harmony in the Jewish tradition and to be implemented in concrete Jewish life and rituals. The gap between heaven and earth was to be bridged by his halakhic work. Time and again, the diary documents how specific Talmudic discussions and their ramifications that preoccupied Karo due to his responsibilities as rabbi, judge, community leader, or public preacher were discussed in the Divine Yeshiva. At times he was provided with an assurance that his mode of reading or interpreting certain Talmudic discussion (sugiya) was correct, and it even filled the almighty God with satisfaction and aroused a smile. Beside the political-institutional aspects of his codification project, discussed in other chapters, the law had turned into axis of salvation.

The general exile of Iberian Jews in late fifteenth century was followed by waves of immigrations across the globe, weaving international networks of political, economy, family, and religious ties. This process eventually led to the establishment of two main Diasporas. The “Western Sephardi” Diaspora in Western and Northern Europe was influenced by Christian traditions under centralizing states and maritime empires. A parallel network, the “Eastern Sephardi” Diaspora, was deeply immersed in Ottoman-Muslim civilization and the Arab lands. The differences between the two traditions related to their use of languages, religious changes, economic activities, and political affiliations—Christian Europe or Ottoman Islamicate traditions. The Ottoman diaspora extended along vast zones, but its main actors lived and prospered in several important cities in the Ottoman Empire—such as Istanbul, Salonica, Edirne, and later Izmir—and in the classical Arab lands occupied by the Ottomans in the early sixteenth century, including the cities of Damascus, Cairo, Jerusalem, and Safed.

During the first half of the 16th century, Safed became a vibrant hub of Jewish life due to its economic prosperity. This enabled the city to attract several waves of Jewish immigration from across the Mediterranean basin. The city still comprised a relatively small Jewish population, however, and in most respects could not compete with the large and established communities of major Ottoman cities, such as Istanbul or Salonica. Yet there was one aspect in which Safed enjoyed a significant edge over these cities: Torah and Talmud scholarship, in particular, and erudition, in general. Several foci of Talmudic scholarship were founded during the 16th century along the Mediterranean, sparking a veritable renaissance in Talmudic and juridical studies in the eastern Sephardi Diaspora. This expansion was noticed by contemporary observers and was reflected in an impressive volume of responsa literature, increasing numbers of scholars dedicated to studying the Talmudic and post-Talmudic heritage, and also the expanding activities of religious courts. The important Yeshivas (Beit-Midrashim, in Sephardi parlance) were headed by impressive scholars whose writings and juridical concepts inform Yeshiva studies to the present day. The importance of Safed lay in the fact that it hosted some of the leading scholars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, R. Karo included.

The city of Safed had another and more significant advantage over other major communities in the Ottoman Empire: it was located in the Holy Land, the object of longing of the entire Jewish Ecumene and the fountain of its heritage. It thus served as a kind of “capital city” of Jewish religiosity and as a destination for Jewish pilgrimage, as did Rome in the Catholic world and Mecca and Medina in Islam. No less significant was the proximity—very sensual and geographical—of Safed to the area where the mythical stories of the Book of Splendor (Sefer Ha-Zohar) took place—the mystical corpus that provided the basis and inspiration for the pietistic and mystical renaissance of Jewish tradition in the early modern period. This was the first time in Jewish religious history that secretive traditions crossed the boundaries of esoteric circles and reached somewhat larger parts of the Jewish population. In this specific aspect, no other Jewish community in the Ottoman Empire, and certainly not in Europe, could compete with Safed.

The Jewish elites in Safed—Kabbalistic, Talmudic, pietistic, and liturgical—were the first to promote and proclaim the sacred stereotype of their city. The proximity to the concrete arena where the divine secrets were revealed to the Zoharic mystical confraternity was not coincidental. The place was deemed fit for Torah study and for vicinity to God: “Safed is propitious to achieve the depth of Torah and its secrets, for there is no fresh air in the entire Holy Land such as in Safed,” as an adherent of Safedian Kabbalah proclaimed in the seventeenth century. The printing of the section “New Zohar” in Salonica in 1597 included the heading “There is no Torah as the one in The Holy Land, it became famous in all places, i.e. Safed may it be erected and glorified, Amen.” The glory of the Sanhedrin as a leading scholarly center and juridical instance—a kind of pristine Supreme Court of Law—had now as if shifted to Safed. The sanctity of the city and the high prestige of its sages were reflected by the almost folkloristic habit of Sephardi merchants around the Mediterranean of reinforcing their statements by swearing on the name of Safed sages.

Safed was presented as a sanctified enclosure, a place in need of solid economic or financial basis for its subsistence, since its main essence lay in Torah study. The presence of so many impressive scholars provided some factual support for this stereotype of a holy city. It encouraged the construction of an international network of charity and support for the local scholars. Eyal Davidson collected several comments reflecting this status. In one of them, a person inheriting some property claims: “The subsistence of the Yeshivah is the reason for living in the Holy Land [more specifically in Safed], since this place is not intended for business and worldly activities.” Local scholars and visitors from abroad idealized the city as a place replete with Torah wisdom, not only among the “professional” scholars but also among the Jewish population in general. Safed is a fountain of wisdom for the entire Jewish Ecumene, providing further motivation for supporting the city by charity. The construction of this image of Safed could certainly rely on concrete facts, since famous rabbis encountered the public at large in local synagogues, where they would preach and teach Halakhah.

No wonder that local rabbis and leading Talmudic scholars attempted to turn Safed into a focus of Jewish legal authority. They were increasingly involved in the legal disputes and complicated juridical issues raised in other communities around the Mediterranean Basin, going as far as Italy and Provence. They did not hesitate to use threats against rebellious persons opposing their authority, or alternatively to plead for cooperation by those faraway communities, lest the honor of the Safed rabbis be tarnished. A letter sent in 1560 from Avignon begged the Safed rabbis to act harshly against a person intending to proceed with a levirate marriage:

The clarion call horn issued from your court [in Safed] would make the doorsteps tremble […] Thus you, angels of God, sitting on a high chair, authorized as the Sanhedrin in the holy precinct of the Temple, do not spare them [all the persons involved], and curse and excommunicate them in all the synagogues and Talmudic schools [again, in Safed] […] and order all communities not to join them in ritual acts, and allow all Jews to harm them physically, or to hand them over to non-Jewish courts, so as to harm their bodies and property.

Over the course of the 16th century, the dominant status of Safed was manifested in another area, as its scholars and leaders assumed responsibility for collecting charity for the poor and needy population of the entire Holy Land. In 1600, R. ʽAmram “the Ascetic” (Ha-Nazir) was sent on behalf “of the Sages and leaders of Safed” to collect all the entire charitable donations from Europe, passing via Venice, to the Holy Land. The money would arrive as a lump sum to Safed, and the local scholars would take care to divide it among all the Holy Land communities.

R. Joseph Karo was not the first Jewish rabbi to act in the interface between halakhic expertise and immersion in mystical life. But he was certainly the most prominent and effective example of this phenomenon. His deep commitment to a mystical vita activa was documented in his mystical diary Magid Meisharim, a remarkable and exceptional document in Kabbalistic and rabbinical tradition until the sixteenth century. The interface between a highly professional occupation with law and mystical activity is a rarity in Western or European tradition, yet it is a common and native occurrence in Islamicate tradition. In this sense, the life course of R. Karo integrates smoothly with the Muslim tradition of his surroundings. Further, it corresponds with the Ottoman culture of the time, within which he prospered, and which was well-known to him and his generation. Law and mysticism are not two distinct hats worn by the same person, but two complementary occupations. Law and legal traditions were key aspects in the political ethos of Ottoman and Eurasian rulers in the early modern period, as fundamental legitimizing factors. These rulers were also often regarded as providers of law and justice and as people of saintly and mystical character.

By the time R. Karo arrived in Safed, he was already an adult and an established halakhic scholar. Over the coming years, he would gradually reinforce his position and come to be recognized as a major figure in early modern Jewish culture. The publication of his double codes of law—Beit Yosef and Shulchan ‘Arukh—during his lifetime, and while he was living in Safed, placed him at the top of this dense scholarly environment. No less noteworthy is that R. Karo was involved in deep mystical experiences that intensely affected his concrete activities and life course. It is impossible to reconstruct exactly when and under what circumstances R. Karo embarked on his Kabbalistic path, but it is apparent that one of the constitutive moments along his mystical course occurred during the Pentecost festivities in Salonica in 1533. Pentecost (Shavu‘ot) is celebrated as the moment of the Granting of the Torah at Mount Sinai. Kabbalistically viewed, it is perceived not as a one-time historical event, but a recurring mythical symbol of the unique and continuous pact between God and His people through the Torah; a pact that is renewed in every act of Torah study.

R. Salomon Alkabetz (1500-1576), an inspiring and charismatic Kabbalistic figure, and R. Karo jointly headed a mystical fraternity in Salonica. It is highly plausible that some of the fraternity members were Talmudic scholars and disciples in the prestigious Yeshiva headed by R. Joseph Taitatzak (1465-1546), who himself experienced angelic revelations alongside his important halakhic scholarship. Toward midnight on the festival, they convened and began to read texts from the Jewish canon or more precisely to chant them with a certain intonation. Divine inspiration descended on R. Karo, and he spoke on behalf of the Shekhinah, the revelatory and feminine aspect of divinity according to the Book of Splendor (Sefer Ha-Zohar). Disappointingly, not all the members of this secretive fraternity were present during this night, which caused the divine voice to rebuke those absent. On the following night, the number of participants increased and the same ritual cycle was followed, again opening the door to further and even deeper revelations by R. Karo.

The testimony of this event was left by Alkabetz, who obeyed the instruction of the Shekhinah and migrated to the Holy Land, later followed by R. Karo himself. The letter documenting this event is not a direct and unbiased testimony but saturated with rabbinical and literary rhetoric. The divine voice is described as using a literary and flowery language, echoing the classical poetry of Sephardi tradition. The allusions to the rabbinical heritage place the event in a triple context: First, as the reconstruction of Mount Sinai revelation—the formative moment in the construction of the historical link between God and his people; second, as the encounter of scholars of Yavneh after the destruction of the Second Temple, a constitutive moment in rabbinical tradition; third, the fraternity members attending the sacred moments bore the same titles as the mystical fraternity of the Zohar, implying that they existed in historical time, carrying on their mystical secrets in the settings of the early modern world.

The deep attachment to Sefer Ha-Zohar during the two-night Pentecost event would continue throughout the early modern period. This work would eventually become the mystical canon of Jewish culture, relegating to the margins other and previous mystical traditions of the Middles Ages. The event also explains the mystical commitment of R. Karo to these Zoharic traditions as a fundamental point of reference in his future years. The suggestions offered by the Zohar, or in the writings of its principal composer R. Moses di Leon, to project mystical aspects of divinity into parallel ritual activity were transformed into concrete reality in the mystical fraternity of Alkabetz and Karo. This is the first testified occasion on which such a ritual event of convening and reading sacred texts, inspired by Kabbalistic motivations, had taken place on the night of Shavu‘ot. The entire happening was documented so that it would reach further circles, and indeed during the sixteenth century what took place in Salonica inspired other people as well, and became a ritual practice celebrated to the present day. The ceremony is known as Tiqqun Leil Shavuʽt, literally “the Emendation of Divinity during Pentecost’s Eve.”

The event directed and confirmed Karo’s mystical itinerary for future years. He would be deeply involved in mystical, scholarly, juridical, and leadership roles, all of which were regarded as inseparable. The revelations he experienced in Salonica were public, in the sense that the messages were heard by other persons as well and were not confined to some inner or mental process. They were instantly accepted as legitimate and sacred, and not challenged as false or demonic. What is even more important is that the pattern of revelation established in Salonica would continue for the rest of his life: the revealing figure is predominantly feminine, mostly under the guise of the Shekhinah. Additionally, the technique for reaching these mystical moments was related to some form of musicality and the recitation of a sacred text. The term used by Alkabetz in this regard, borrowed from the Song of Songs—Qol Dodi dofeq—would become a common refrain in Karo’s mystical diary.

It was not mere coincidence that neither R. Karo’s revelations at Pentecost nor his broad mystical enterprise were challenged as false or inadmissible. Again, Karo was responding to a changing religious atmosphere in early modern Jewish Diaspora around the Mediterranean Basin whereby revelations of various kinds were increasingly regarded as legitimate. In the late fifteenth century, prior to the general expulsion of the Iberian communities from Spain (1492) and Portugal (1497), the “Book of Splendor” circulated in relatively esoteric and restricted channels and had not yet achieved the status of a canonical book. This changed dramatically in the mid-sixteenth century, due to the rise of Safed as a leading Kabbalistic center and following the double printing of Sefer Ha-Zohar in Italy, the center of Jewish printing in this period.

The change in religious atmosphere was inspired by yet another set of writings, known as the “Book of the Respondent” (Sefer Ha-Meshiv). This is a fiery discourse on revelations and the capability to establish a bridge between an inspired Kabbalist and the divine sphere, intermediated by a Magid, some kind of angelic figure. Karo adopted this term, which later formed part of the title for his mystical diary Magid Meisharim. The time, according to the anonymous Sephardi composers of Sefer Ha-Meshiv, was suitable for unprecedented revelations of hidden Torah secrets, as the messianic era was imminent. As Idel and Scholem noted, the Magid was a new actor in Jewish mystical tradition specific to the sixteenth-century context. Though not derived from any direct Talmudic sources, and certainly not suitable to legalistic mindset of the rabbinical ethos, it was not rejected by the rabbinical authorities. R. Joseph Taitatzak, the leading Talmudic scholar of Salonica, one of the main centers of Sephardi erudition in early modern period, was known “to have a Magid.”

Sixteenth-century religious life in the Jewish communities of the Mediterranean Basin was suffused with similar types of revelation. The rising Kabbalistic domain provided various channels for bridging the gulf between humans and the ineffable God. The binary distinction between God and man, good and bad, and sanctified and polluted was filled with intermediary entities that could help the believer to approach God more intimately or conversely impose obstacles: the tree of souls, reincarnations, impregnation, treasure of souls, and demonic torture instruments related to the human body, birth, and death. Mental life became a complex balance of reward and punishment reverberating between the poles of sanctity and pollution, Shekhinah and the demonic, angels and demons, the eternal life world and the world of the dead. Kabbalistic creativity permitted passage between the material world and the hidden world, mutually intertwined by reincarnation and possession, spirits, demons, Magidim, and angels.

The evolvement of print technology, especially the printing of Sefer Ha-Zohar and other Kabbalistic literature over the course of the sixteenth century, made it possible to share this dichotomous Kabbalistic attitude among broad lay circles. An entire spectrum of agents and techniques and ritual practices played on this stage: Magidim, dreams, prophecies, trance states, reincarnations (gilgulim), impregnation (‘ibbur), demons, and black magic, angelic figures, dreams, Elijah “the Prophet” as a source of mystical secrets, attachment to masters and to a Righteous Person (tzaddiq), and finally pilgrimages to sacred graves. Even the body was not immune to infiltration by supra-human elements, as testified by the dramatic increase of possession cases and their public and theatrical shows of healing. It was a suitable arena to present the dividing lines between the forbidden and normative and to enhance social control.

The insertion of Sufi individuals, institutions, and religious heritage into the Ottoman state benefitted both parties. Again, it was not confined to the Ottoman context but characterized their political rivals in the Safavid and Mughal areas, as well as the rising empires in Europe. The important works of Hüseyin Yılmaz, Kaya Şahin, Christopher Markiewicz, and others illuminated the role of leadership in fusing aspirations for universality, a messianic role, and personal sanctity. The Ottomans envisioned the caliphate as a comprehensive cosmological position that encompasses both temporal and spiritual realms. This perspective was embroidered in discursive narratives constructed by dynastic apologists and enigmatic writers, as well as by mainstream scholars through literary articulation, artistic representation, and occultist revelations. The caliphate myth was part of the imperial ideology, claiming that the House of Osman had been commissioned to rule as the “Great Caliphate” of the end of times foretold in the Qur’an, prophesied by Prophet Mohammed, envisioned by saints, and proven by discernible manifestations of divine providence. This political myth was closely tied to an eschatology drawn from indigenous traditions and Abrahamic teachings conveyed via Islamic sources.

It is important to note that this eschatological vision of rule was not confined in the Ottoman case to the ruling elite but was mediated by political, literary, and visual means to wider circles of the population. In the age of Süleyman, writing on rulership and government became part of a public discourse where ordinary scribes, obscure mystics, low-ranking provincial commanders, and poets with no training in statecraft could write on political matters.

There was a further channel for disseminating the ideal of sacred ruler. The fusion of religious and political elements such as personal sanctity, charismatic authority, and visions of earthly political rulership motivated several Sufi leaders of popular movements to aspire for leadership, and even to rebel against the Sultanic authority.

A conspicuous person in this regard is Ibrahim Gülşenī (1423-1540) presented in detail by Side Emre. Side Emre situates Gülşenī among several ḳutb/mehdīs who survived trial and persecution by the central Ottoman government in Istanbul. While Gülşenī does not claim, in his surviving poetry, to be the mehdī, at least one of his better-known deputies did, and suffered the consequences. Kāşifī, a deputy to Gülşenī, claimed to be the messiah of his age during the first decades of Süleymān’s rule, and despite his reputation as mentally instable was executed as a result of these claims. Aspirants such as Kāşifī harbored political missions, with the apocalyptical atmosphere surrounding them. These ideas echoed widely and reached wide places in the Muslim Mediterranean, as far west as Morocco, spurring Messianic-Mahadist hopes and activities.

The project of Sunnitization went hand in hand with the suppression and marginalization of the non-Sunni elements among the empire’s Muslim subjects, as well as the enactment of more proactive measures to establish Sunni orthopraxy in the Ottoman domains.The law further added as a factor of increasing orthodoxy, beyond the classical role of guiding the believer’s life: “In the late 16th and early 17th centuries shariah-abiding ‘sunnitizing’ Sufi from such orders as the Halvetiyye and Celvetiyye played an even more active role than the top ranking ulema in propagating in what might be best called state Sunnism.” The spread of Sufi orders, their insertion in state mechanisms, the political ethos of the saintly ruler, the apocalyptic expectations and renewal of religion, the tight linkage between mysticism and law, the composition of guidance tracts aiming at the public at large, and the sharper borders between correct belief and heresy—all created the foundation for the life projects of R. Karo.

The multiple points of similarity between the diary of R. Karo and his somewhat later Sufi master Niyazi el-Misri reveal how deeply they both share the same cultural platform of Islamicate and Ottoman civilization. The Sunnitization process of the Ottoman Empire during the life span of R. Karo, masterfully analyzed by Derin Terzioǧlu and Tijana Krstić, became significant as a state project. In constructing an empire of unprecedented geographical extent and ethno-religious diversity, the Ottoman elite mobilized both people of the law—the ʽUlama and the Madrasa heritage—and impressive masters of various Sufi orders. It was not uncommon that religious scholars would embody both these domains in their studies and public activities. The political paradigm of the Ottoman sultan and state blended together aspirations for military campaigns, religious innovation, messianic hopes, and Sufi traditions—all under the umbrella of law and justice. For R. Karo, it further offered a vision for religious renovation and reform in which the law enjoyed universal horizons of applicability throughout the Jewish Ecumene. Such a vision fell on a fertile ground of a Jewish heritage of universal justice dating back to the biblical prophets.

Karo did not have access to any political tools or instruments of coercion. But his vision directly projected into the Jewish environment the same vision of law as a channel to salvation. He would study Talmudic lore as a regular scholar, yet in tandem he related his Talmudic devotion to mystic terminology and presented it as a continuous encounter with the Divine Yeshiva and its past scholars; suggested pietistic model of devotion and adherence to God (devequt), and ultimately dreamed of becoming the leader of the Jewish Ecumene: “It is I, the Mishnah, speaking through [or: in] your mouth, the mother castigating her sons [or children], the one embracing you. And you shall often adhere to me, I shall return to you and you shall return to me. I shall raise you to become master and leader (sar ve-nagid) over the entire Jewish Diaspora in Arabistan.”

Reprinted from Roni Weinstein, “Joseph Karo and Shaping of Modern Jewish Law: The Early Modern Ottoman and Global Setting” (2022), with permission of Anthem Press.

Roni Weinstein is an historian of early modern Jewish history, and teaches at the Rothberg International School of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.