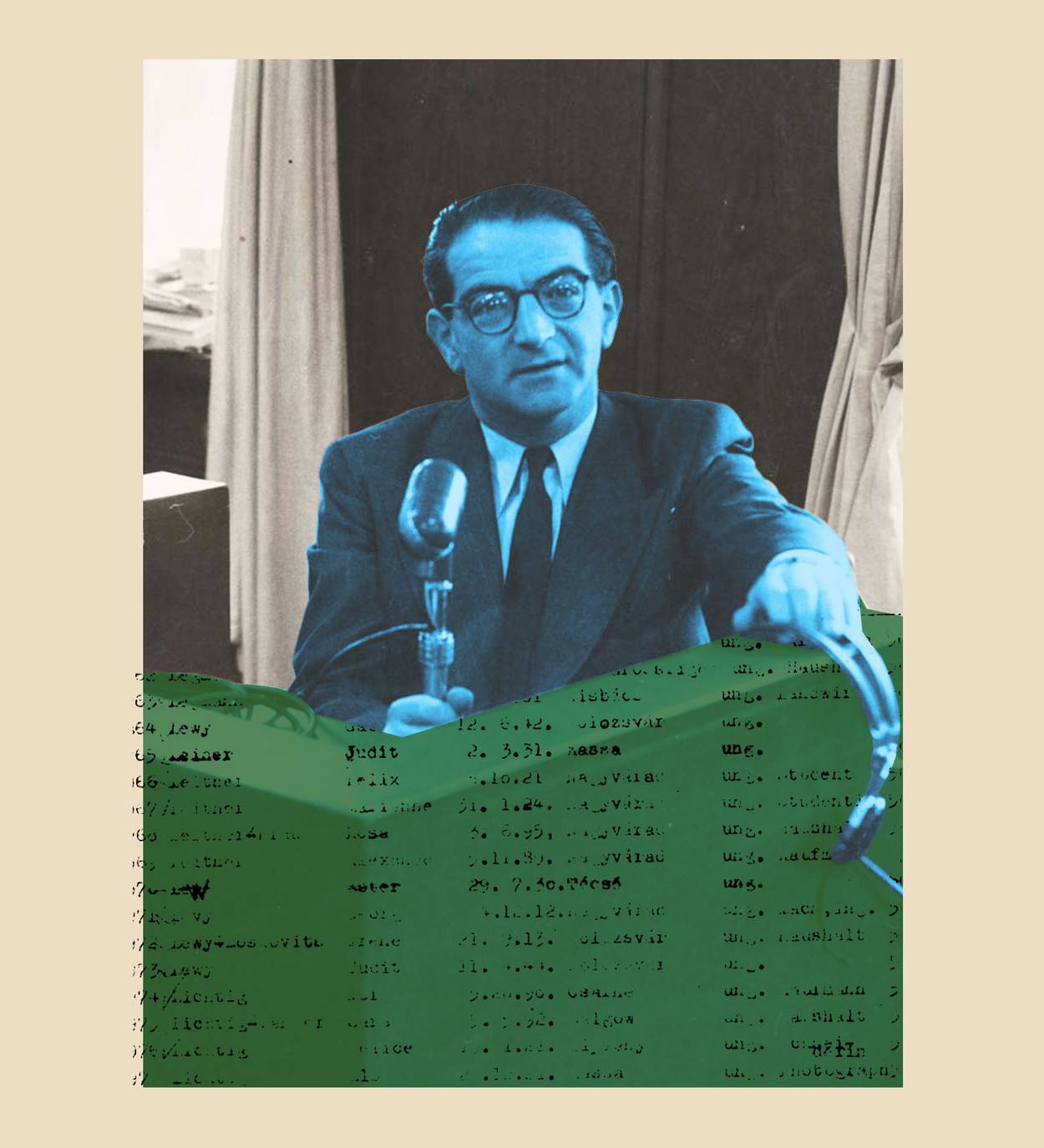

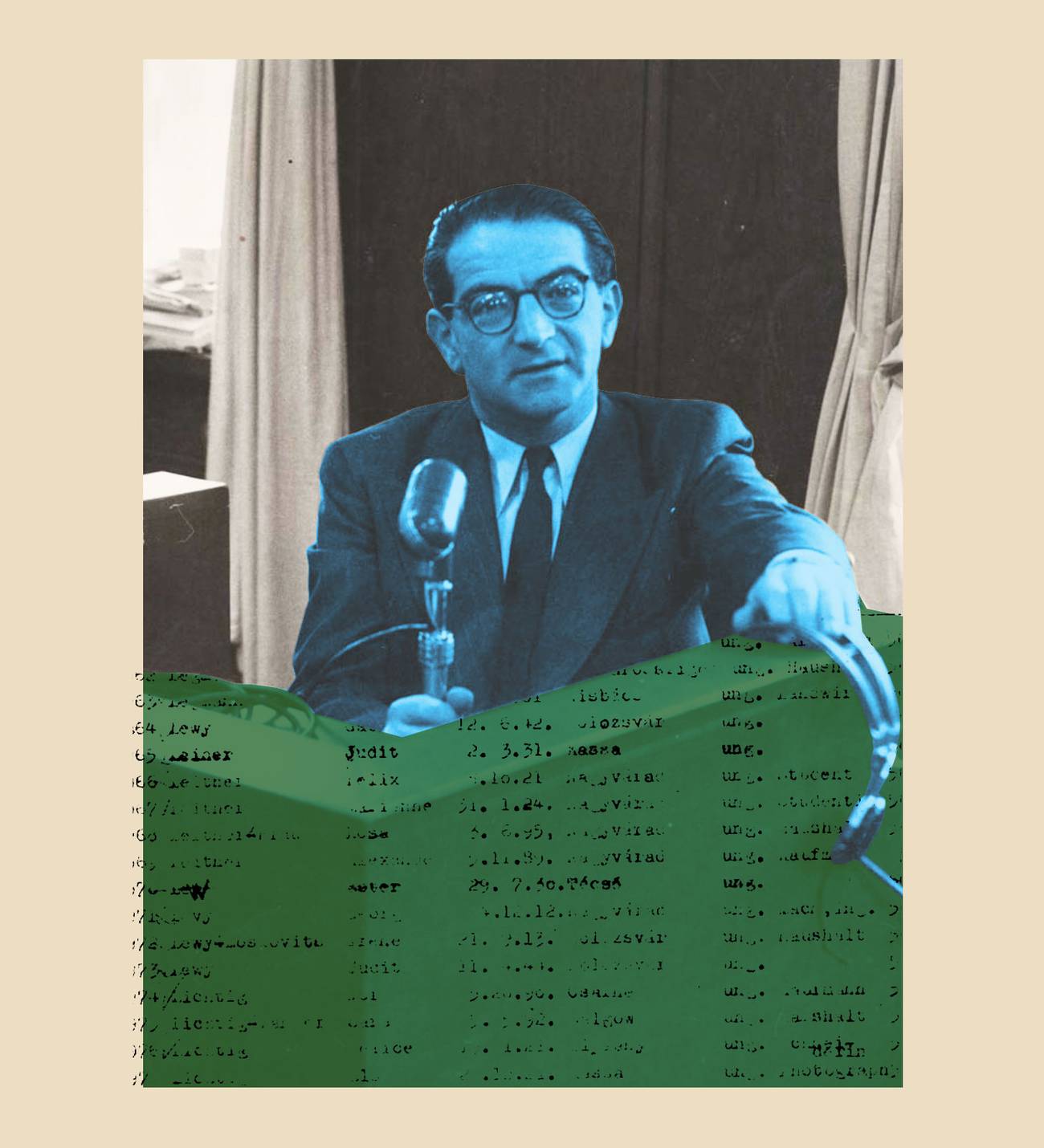

It is astonishing that, 64 years this month after the events that led to his murder, Rezso (Rudolf) Kasztner is still a controversial figure. Lauded as a savior by some, condemned as a collaborator by others, accused of failing to warn more Jews about the death camps yet celebrated by the children and grandchildren of those he did save. In 2018, Merav Michaeli, Kasztner’s granddaughter and the current leader of Israel’s Labour Party, lit candles in the Knesset in honor of her grandfather on Holocaust Remembrance Day. In February 2021, she spoke again about her grandfather in response to “hateful words” uttered about him in the Knesset:

“I would like the record to include the following: Dr. Kasztner was my grandfather. He was a lawyer, politician and a journalist … What brought on the murder of this Zionist activist, the savior of many Jews, was the horrendous incitement by the extreme right in ’50s Israel, relentless, organized incitements for political gains, as many saw this opportunity to overthrow Ben-Gurion and his party. This was the purpose then and this is the purpose for the incitement today.”

Kasztner has remained a hero to most of the 1,684 passengers on what became known as “Kasztner’s train.” They traveled to Switzerland after a short stay at the notorious Nazi concentration camp Bergen-Belsen. A veritable Noah’s ark of Hungarian Jewry, the train carried young and old, Zionists and Orthodox anti-Zionists (the Satmar rebbe was on board), musicians, laborers, shopkeepers, politicians, an opera singer, and a couple of refugee children from Poland. One hundred fifty of the passengers paid in cash, gold, and jewelry; the others paid nothing. Kasztner’s efforts to save another 30,000 people, which shrank to 20,000 (Hauptsturmführer Argermayer reported 20,700; some historians have claimed only 15,000) toiling as slave laborers in Austria have been discredited by some as an invention, though the records exist. He was also blamed for the fact that a quarter of those who were sent to Austria through the Strasshof camp died, though the numbers would surely have been far higher without his intervention.

I first came to Kasztner’s story with no predetermined notions about whether he was a villain or a hero. I had read Ben Hecht’s Perfidy, a description of Kasztner’s trial in Jerusalem, and I had heard the Canadian businessman Peter Munk talk about his family’s escape on the Kasztner train. I read the documents, the books, the memoirs (in three languages), searched several archives, watched the documentaries, and interviewed over 100 people. Some believed that Kasztner could have warned thousands more of their impending doom, seemingly imagining that they would have fought the Hungarian gendarmes with their bare hands had they known about Auschwitz. Others spoke of how such warnings would have been impossible. And still others said that everyone already knew what to expect of the Germans; they just didn’t want to believe that such brutality was possible in Hungary.

I spent several years researching and writing a book called Kasztner’s Train, in which I concluded, in the end, that Kasztner was a heroic figure at a terrible time, when such heroism could and did amount to the difference between life and death. I had wanted to know who Kasztner was, what motivated him, how he managed to play such a high-stakes game with Adolf Eichmann, one of the chief architects of the Holocaust, and why he was put on trial in Israel, where the judge deemed that he had been a collaborator.

Rezso Kasztner was born in Cluj, a provincial town with cosmopolitan pretensions on the eastern edge of what used to be the Habsburg Empire and is now Romania. A young, idealistic Zionist who believed that Jews needed a home of their own, he became a lawyer, a journalist, and a junior functionary in the new Romanian parliament. He married Elizabeth (Bogyo) Fischer, the daughter of an influential and wealthy man. When Germany invaded Poland and refugees started to arrive, Kasztner collected donations from the wealthy to buy them food and clothes and, if possible, pay for their passage to Palestine.

After Hungary invaded Romania to reclaim the territories it lost at the end of World War I, Kasztner’s newspaper was shut down as part of the newly imposed anti-Jewish laws. He went to Budapest to look for work and to find more donations for refugees. There, he joined the newly formed Aid and Rescue Committee under Ottó Komoly, where he met and befriended Joel and Hansi Brand.

The committee continued its work after the German invasion of Hungary in March 1944. They prepared fake documents, supplied food and clothing for the dispossessed, and looked for ways to bribe SS officers to save more lives. Brand and Kasztner presented themselves to SS authorities in Budapest as credible representatives of that mythical “world Jewry” that Hitler believed ran the world. And they negotiated with Adolf Eichmann and his unscrupulous band of SS officers for human lives.

He was also blamed for the fact that a quarter of those who were sent to Austria through the Strasshof camp died, though the numbers would surely have been far higher without his intervention.

Those who had known Kasztner personally said he was brilliant, focused, unflinching, often brash, an intellectual, well aware of his own talents, unusually brave, unrelenting, but with a sense of irony. Nonetheless, Hansi Brand said that he was so scared of going to see Eichmann that she had to help him practice a cool, steadfast attitude, since the Germans would not respect, let alone deal with, a man who was afraid. She taught him how to chain-smoke and whack his heels against the parquet floor as he marched.

Peretz Revesz, the Hungarian rescuer whose own book details his experiences as a young Zionist working with Kasztner and the Brands to save children, regarded him as among the strongest, most dedicated of men. While he didn’t personally like Kasztner or what he saw as his savior complex, he respected Kasztner’s ability to rise to the occasion. He also found the notion that Hungarian Jews—perhaps the most assimilated of all of Europe’s Jews—could have resisted the Nazis to be ridiculous. “The young men were in the labor brigades, we had 40 pistols, little ammunition, some knives,” he said.

In a 2018 Tablet article, Tomi Komoly, Ottó’s nephew, writes about the “blood for goods” deal proposed by Eichmann—in which the Germans would exchange a million Jewish prisoners for 10,000 trucks—which Joel Brand was to relay to the Allied leadership via Istanbul. In hindsight, it is obvious that Eichmann lied about the number of Jews that it might be possible to save, since deportations to Auschwitz began even as Hansi Brand and Kasztner kept up the negotiations. Nor was there much of a chance that the Allies would in fact ship trucks to the Germans during the war.

In his newly-published book, Trapped by Evil and Deceit, Daniel Brand, Hansi and Joel’s son, writes about the “Jews on ice” deal that Kasztner and Hansi brokered while conducting their kabuki theater negotiations: Trains carrying a down payment of Jews were diverted to Strasshof, Austria, and thence to wherever laborers were needed. According to Hansi’s testimony at the Eichmann trial, the deal entailed keeping alive even those who could not work, especially young children.

An undated photo of the Kasztner train in Switzerland. The photo was taken by Zadok Raab, one of the passengers.Memorial Museum of Hungarian Speaking Jewry

Kasztner’s continued negotiations with SS Lieutenant-Colonel Kurt Andreas Becher led to the rescue of 1,684 Jews in exchange for money, gold, jewelry, and promises of more. Several times, Kasztner traveled to the Swiss border with Becher and his adjutants for meetings with the Swiss representative of the JOINT, to discuss items aside from trucks that the Reich would accept in exchange for Jewish lives. Though he could have simply stayed in Switzerland, a neutral country, Kasztner always returned to continue the negotiations for more.

At the end of the war, with Allied victory now certain, Kasztner returned again to personally accompany Becher to several concentration camps, working to counter SS Obergruppenführer Kaltenbrunner’s orders to murder all the remaining prisoners. It is irrelevant that Becher was now looking out for himself, worried about his own fate after Germany lost the war. There is also no doubt that SS officers Hermann Krumey and Dieter Wisliceny, both of whom had been active participants in the dispossession and murder of Hungary’s Jews, helped keep the Strasshof Jews alive in Vienna in order to provide alibis for themselves once the war ended. What matters is that lives were spared.

When Rezso Kasztner emigrated to Israel with his wife in 1947, he was disappointed that he did not receive a hero’s welcome. After all, he had played a deadly poker game with the Nazis and had saved thousands of lives. But few people in the newborn state were interested in discussing the Holocaust. Instead, Kasztner found work as a journalist and as a spokesman for Israel’s Labour-led government.

It was at the request of the government that Kasztner returned to Germany to testify on Becher’s behalf at Nuremberg. The Israeli government had hoped that Becher would help them recover some of the Jewish assets he had purloined in 1944 and trade them for guns and ammunition they rightly expected they would need. Kasztner also gave supporting testimony on behalf of Krumey, for helping him buy clothes and food for the Strasshof detainees, and on behalf of Wisliceny, because he had been the last to see Eichmann before he left Europe. There was some hope that, with Wisliceny’s information, Eichmann could be arrested and brought to trial.

In August 1952, Malchiel Gruenwald, an Israeli pamphleteer, published an article accusing Kasztner and the heads of the Jewish leadership during and after the war of collaborating with the Nazis. Because of Kasztner’s affiliation with the ruling Labour Party, the state attorney general insisted on suing the author for libel.

The Gruenwald trial soon became known as the Kasztner trial. It was long, arduous, and overtly political, taking over the front pages of newspapers. The accused’s lawyer, Shmuel Tamir, was young, eloquent, and a passionate opponent of the ruling Labour Party who judged Ben-Gurion’s negotiations with the British to be on par with Kasztner’s negotiations with the Nazis. He planned to drag the government down with Kasztner.

Kasztner had hoped the trial would finally show the doubters all that he had done. Yet, many who could have testified on his behalf never came to his aid, and even the testimonies in his defense were disbelieved.

The State of Israel lost the suit. Judge Benjamin Halevi famously said that Kasztner had sold his soul to the devil.

On March 4, 1957, Kasztner was assassinated by Ze’ev Eckstein, an ultra-right-winger who believed the country had been sold to the British by Ben-Gurion’s leftists. Gaylen Ross’ award-winning 2010 documentary, Killing Kasztner: The Jew Who Dealt with Nazis, reveals the complex reasons for the murder, leaving the viewer with no doubt that those who encouraged the killing were as embroiled in the political struggles of the new State of Israel as those who were on Kasztner’s side. The film, like my book, goes some way to revealing what kind of man Rezso Kasztner truly was.

Kasztner’s actions are unsurpassed in the annals of Holocaust rescue. Oscar Schindler pronounced him to have been fearless. He often appeared tough and unemotional, aggressive and outspoken, but that posture was what the situation required. He also had an unquestioned capacity to hold seemingly contradictory ideas and aims in his head while still retaining the ability to act. He combined an enduring marriage to Elizabeth Bogyo with an enduring love affair with Hansi Brand, who was there every day of the trial. Every evening, she gave him advice—most of which, fatally, he ignored.

There is a modest plaque to the members of the Rescue Committee in Budapest and a photograph of the group at Yad Vashem. Had Kasztner been a gentile, there would no doubt be statues of him, parks named after him, and movies made about his daring, nerve-wracking dance with the devil. The enduring question about his life would be how, and why, he had saved so many Jews while repeatedly risking his own life. Instead, with Kasztner, the question that lingers is, “Why didn’t he do more?”