The Price of Redemption

‘Who was I to decide which commandments to obey?’ With searing honesty, an eminent theologian recounts the eclectic educational journey of his training.

Ellen and I began married life in 1947 in a furnished room near Columbia University. Housing was scarce. Our resources were exceedingly sparse. We shared the kitchen and bathroom with a number of people, most of whom were students at one of the institutions in the Columbia-Morningside Heights neighborhood. Our room was on the ground floor facing the street. It had been the living room of an apartment which had seen better days before it was subdivided into rooms for students. We did our best to brighten our room with posters, art reproductions, and an occasional piece of our own furniture. We had little privacy and hardly enough space, but it didn’t matter. We were beginning our marital adventure and we were together. It also helped that most of the other tenants were our age and in a comparable situation.

We both worked. I taught at Temple Israel at first and continued my part-time research job with the Jewish Education Committee. Sam Dresner introduced me to Wolfe Kelman, a student at the Seminary. Wolfe has served almost all of his rabbinic career as executive vice president of the Rabbinical Assembly of America. Shortly after we met, Wolfe helped Ellen to get a job with the Youth Division of the United Jewish Appeal. It was the period immediately before the birth of the State of Israel. Ellen became deeply involved in helping to raise money for the young nation which was about to face its test of birth and war. We wanted to do all we could to help the beleaguered Jews of Israel to become masters of their own destiny.

Wolfe became a very important influence upon me from our first meeting. He was my age but he had far greater experience with the Jewish world. Like Abraham Joshua Heschel, he came from a long line of Hasidic rabbis. He was part of a Hasidic aristocracy of which neither Ellen nor I had had any prior knowledge. His father had been a rabbi in Toronto. After his premature death, Wolfe’s mother brought her family to the Borough Park section of Brooklyn, then as now a citadel of Orthodox Judaism.

Before meeting Wolfe, I had known a number of men who were at home in traditional Judaism but none my own age who were also at home in the secular world. Wolfe introduced Ellen and me to his family. We were frequently invited to share the Sabbath with them. Mrs. Kelman was an attractive woman, deeply committed to her inherited Hasidic traditions. She was raising her family as committed Orthodox Jews under difficult circumstances with great dignity. From earliest childhood Wolfe and his brothers had been at home in the world of Talmudic literature. Knowledge of the complexities of Jewish religious practice was second nature to every member of the Kelman household. No matter what the sacrifice, Mrs. Kelman insisted that all of her children receive as excellent a Jewish education as available in North America. She also insisted that they complete their secular educations as well.

When Ellen and I decided to commit ourselves to a more traditional life, there was something abstract about our resolve. We had little contact with the living tradition. Things changed when we met the Kelmans. Mrs. Kelman encouraged Ellen in her efforts to overcome the feeling that there was something unnatural about what we were trying to do. She also served as a model, perhaps even a surrogate mother. It was impossible to be a guest in her house without being deeply impressed by its spiritual and cultural integrity. We were brought into contact with a religious world that had remained intact in spite of all the assaults visited upon it. We were always mindful of the fact that thousands of households of comparable dignity and devotion had been contemptuously slaughtered by the Nazis. Both Ellen and I had been brought up to look down on Orthodox Jews as backward, unenlightened, and perhaps superstitious. We had good reason to revise our judgment after we met the Kelman family.

The extraordinary dignity of the household intensified our revulsion against the compromises of middle-class Judaism. Learning and piety were the measures of personal worth in the Kelman home. We were immensely impressed by the fact that we had come upon people who could neither be bought nor corrupted by the bourgeois world. The experience was revelatory. With Mrs. Kelman’s encouragement, Ellen became increasingly conversant with the requirements of a traditional household. Soon Ellen and I began to feel somewhat more at home in our new life. However, Orthodox Judaism never ceased to have an element of strangeness for us that precluded our ever making a wholesome adjustment to it.

Given my poor Talmudic background, it was impossible for me to enter the Rabbinical School of the Seminary without further preparation.The Talmud is an enormously complex work that consists primarily of the record of discussions of Jewish religious law, lore, and legend carried on by rabbis in Palestine and Babylonia from about the first to the fifth centuries of the Christian era. The language of the discussions is primarily Aramaic. It is complicated by the ambiguities of its unvocalized and unpunctuated text. A word can often have more than one meaning and one is often uncertain whether a question is being asked or an answer being given. Immersion into the study of the Talmud has been likened to immersion into the sea itself because of the immensity of the work and the difficulties which impede mastery of its contents. Without a skilled teacher, it is impossible to acquire even a rudimentary knowledge.

Unable to enter the Rabbinical School, I entered the mechinah, the preparatory department of the Seminary. I quickly realized that the mechinah would prepare me to pass the entrance exam but little else. The level of instruction was such that I would never have gained any real grasp of rabbinic literature had I rested content with the mechinah’s offerings. I sought supplementary, individual instruction from a young postdoctoral student at the Seminary, Ezra Band* (a pseudonym) of Basel, Switzerland. Although he was not much older than I, Band had received Orthodox rabbinical ordination in Europe and a Ph.D. for his studies in religious thought at Basel, where he had studied with Karl Barth. I was as impressed with Band as I had been with Kelman. He seemed to be a living link to the chain of Jewish tradition that had been almost totally obliterated by the Nazis. He was also a link with a European intellectual life I had learned to respect as a result of my contacts with the refugee professors at the Hebrew Union College. It was especially important to me that he had been Barth’s pupil.

There was, however, something indefinably disturbing, one might almost say demonic, about the man, He was thin and short with a sallow complexion. There always seemed to be a film of the city’s exhaust products on his face which was seldom entirely clear of blemishes. He had a pallid indoors look. And although his movements were quick and energetic, he did not seem very robust. On the contrary, his coloring suggested that his natural habitat was the sidewalk café, the dimly-lit corner booth, and the library carrel; that he was a stranger to the world of nature. He was fascinating to a certain kind of cultivated woman who was perhaps more interested in exploring the hidden, the unusual, and the mysterious than in openly celebrating the straightforward joys of romance. Perhaps a certain boredom with the ordinary had to set in before a woman might take up with Band. When we first met, some of the Seminary students called him the crown prince, because he seemed to be courting Emunah Finkelstein, the chancellor’s daughter. He always wore the longest and most ostentatious prayer shawl when he came, as he did frequently, to those services at the Seminary synagogue that were presided over by Dr. Louis Finkelstein. In spite of his display of piety, he talked a great deal about blasphemy, the holiness of sin, and mystical antinomianism. At one of our earliest meetings, he made the accurate prediction that I would soon find more meaning in the pagan gods of Canaan than in the Lord God of Israel. When his friendship with Miss Finkelstein suddenly cooled, he came less frequently to services at the Seminary synagogue.

According to the Talmud, a man’s rabbinic teacher is more important to him than his own father. One’s father brings one into this world; one’s teacher brings one into the life of the world to come. Ezra Band was my first teacher of Talmud. I can no longer remember what tractate he chose for instruction, but I have vivid memory of his long digressions on Sören Kierkegaard, Paul of Tarsus, and Sabbatai Zevi. Band’s theological strategy was to demonstrate the impossibility of all commitments devoid of religious faith. He sought to generate faith out of horror of the secular alternatives. He was, however, perhaps more skillful than any secular humanist I had ever met in arguing for the very world without God he called upon me to reject.

I had no problem with Band’s dialectical approach to belief in the existence of God. My own turning to traditional Judaism was largely based upon a similar dialectic. I was convinced that I was confronted with the necessity to make a spiritual decision: I had either to choose a Godless world, whose quintessential expression was Auschwitz, or obedience to the commandments of the Lord God of Israel. Out of fright and despair I chose the Lord God of Israel.

Nevertheless, there was always danger of backsliding because a life of obedience to the commandments was fundamentally out of keeping with my normal lifestyle. It was therefore necessary for me constantly to be mindful of the perils of such a retreat. As a result, I became fascinated with the more prominent forms of mystical antinomianism as they had surfaced in Jewish history. I saw Paul of Tarsus’s proclamation that Christ is the “end of the Law” as the classical expression of mystical Jewish antinomianism. I mistakenly regarded Paul’s proclamation of the “end of the Law” as opening the floodgates of moral and ethical subjectivism within Christendom. One of my spiritual alternatives appeared to be the choice of either the antinomianism of Paul or the halakhah, the body of Paul or the halakhah, the body of the Jewish law and tradition to which Ellen and I were committing our life. Paul’s way seemed to lead to a thoroughgoing moral anarchy in which all things including Auschwitz would be permitted. The way of halakhah alone seemed to offer a life of moral security.

Between Talmudic discussions of an ox which gored a cow, Ezra and I discussed Paul’s “antinomianism.” On the surface Paul’s proclamation of the “end of the Law” was an expression of the spiritual wasteland we had rejected. At another level, we were both fascinated with the rabbi who became Christendom’s greatest and most perennially influential theologian. We were also intrigued by Sabbatai Zevi, the heretical seventeenth century messianic pretender. We were strongly influenced by Gershom Scholem’s great work Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, which had been published in 1946. Scholem’s work has been perhaps the most influential single work of Jewish scholarship published in the twentieth century. When it first appeared, his chapter on Sabbatai Zevi had an almost revelatory character for me. Sabbatai Zevi’s strange career can be reckoned to have begun in 1648 when Bogdan Chmielnicki, a Ukrainian rebel, led his people in revolt against their rapacious Polish overlords. At the time the Jews of Poland and Ukraine were caught between the Polish landowners and their Ukrainian peasant tenants. Denied access to more normal ways of earning a living, many Jews were compelled to become tax collectors for the Poles, and, as such, despised by the Ukrainians. In their revolt, the Ukrainians slaughtered over one hundred thousand Jews. This was the greatest catastrophe endured by the Jews until the time of the Nazis.

The condition of the community plummeted to a level of desperation hitherto unknown even during the worst anti-Jewish outbursts of the Crusades. The question of when and how redemption would come assumed an unprecedented urgency. When Sabbatai Zevi, a man of manic-depressive tendencies, was proclaimed the messiah of Israel in Palestine in 1665, a very large proportion of Europe’s Jews permitted their yearning for redemption to convince them that redemption was actually at hand. Many were so convinced that Israel’s redeemer had come that they sold their possessions to make ready for the miraculous return to the Holy Land.

Shortly after Sabbatai Zevi was proclaimed messiah he was brought to Adrianople where Turkish authorities gave him the choice of conversion to Islam or execution. The “redeemer” of the Jews chose to become an apostate! Confronted with the apparently disconfirming evidence of the messianic pretender, the Jewish world was forced to choose between a totally unanticipated kind of credo quia absurdum, the affirmation that its hopes were in the process of being realized by its apostate messiah, or the dreary recognition that the community had been tragically deluded by its own hopes. Hundreds of thousands of Sabbatai Zevi’s followers were so dependent upon the joyful promise of redemption that they could not cease believing in him even after his defection.

Sabbatian theologians offered a mystical interpretation of his conversion. They contended that it was part of God’s plan that the messiah became an apostate. The evil that impeded redemption was too great to be overcome by mere goodness. The messiah had chosen a more effective way to overcome evil, the redemptive holiness of sin. He had chosen to descend to the depths of iniquity and impurity to overcome those cosmic forces opposed to God’s plan. Sabbatai Zevi’s followers were divided on the question of whether they were to act out the messiah’s strategy to foster redemption in their own lives or whether the messiah’s immersion in evil sufficed. The radical Sabbatians proclaimed the sacramental character of acts that negated the surface meaning of God’s law. They also asserted that it was necessary for the believer to imitate the messiah’s redemptive negation of the Torah. This was especially true in the sexual area. Formerly pious Jews practiced all kinds of sexual excesses as an expression of the distinctively Sabbatian version of the messianic “end of the Law.”

From the perspective of traditional Judaism, it was clear that, in their cosmic impatience, the Sabbatians were sinful in attempting to bring about the end before the time of redemption had been fulfilled. I saw Sabbatianism as an object lesson of the dangers of religious enthusiasm and the failure to maintain observance of the halakhah in all strictness. When I studied the Talmud under Band’s tutelage I saw myself as literally upholding by my life and learning the forces of cosmic discipline, order, and morality against the antinomian moral excess which the Sabbatians and their spiritual heirs had bequeathed to mankind. I was especially impressed with Gershom Scholem’s assertion that Sabbatian antinomianism was one of the underground sources of the Reform Judaism I had so recently rejected. I saw every Orthodox rabbi as a heroic guardian of civilization, morality, and decency against the anarchic outrages of moral chaos. I wanted to be one of the guardians.

I hovered between love of God and dreams of sinful liberty.

On one level, my Apollonian quest for discipline was satisfied by studying the Talmud and by the interludes of conversation during which my brilliant teacher and I would ponder in horror what life would be like without the law. On another level, the Sabbatians attracted me at least as much as they horrified me. In my daydreams I beheld naked Orthodox Jews, not yet bereft of their beards, gathering in Sabbatian synagogues to enjoy orgiastic sexual coupling with beautiful maidens who lay spread out upon unrolled Torah scrolls waiting to receive the redemptive sacrament of promiscuous love. I imagined unclothed, lustful, dark-haired beauties offering themselves in every imaginable act of love as their mystical identification with Israel’s holy messiah, Sabbatai Zevi. And, of course, I saw myself as one of the wild Sabbatian lovers.

My imagination made me a participant in Sabbatian orgies; my behavior was that of a repressed, overly intellectual rabbinic student who kept the halakhah with ever greater stringency and insisted that his wife wear a covering over her hair whenever she was in public. I also refused to shake hands with women lest mere touch lead to unpardonable adulteries. There was, in all likelihood, a direct relationship between my sternly monogamous ways and the wildness of my Sabbatian fantasies. The daydreams of excess reinforced my zeal to obey God’s law. Undoubtedly, my zeal was a never-ending goad to ever-wilder fantasies. By refusing to touch a woman’s hand, I had eroticized even the slightest contact with the opposite sex.

Could I have been a crypto-Sabbatian? I hovered between love of God and dreams of sinful liberty. Ezra’s personality heightened those tendencies. Ellen and I were simultaneously attracted and repelled by him. One day Ellen was preparing for a Bible lesson in an empty room in the Seminary dormitory. I entered the room while she was engrossed in study. She did not notice me. I came up behind her, put my right hand on her breast and fondled it. She relaxed and became limp. We continued for a few minutes until I broke the erotic atmosphere by speaking.

“My God,” she said, “I thought you were Band. I felt hypnotized and couldn’t resist.” Band had a seductive, disturbing effect on both of us. Band had only a limited amount of time. I required a kind of immersion in the study of the Talmud that was simply not available at the Seminary. Wolfe’s brother-in-law, Rabbi Melech Silber, suggested that I discuss my needs with Rav Yitzchok Hutner, the Rosh Yeshiva or principal of the Mesivta Chaim Berlin. Chaim Berlin was far more strictly committed to Orthodoxy than the better known and more prosperous Yeshiva University. It was also less in direct competition with the Seminary. It was therefore possible to attend Chaim Berlin without compromising my relations with the Seminary.

Chaim Berlin was located on Stone Avenue in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn. In those days Brownsville was a decaying lower-middle-class neighborhood that still retained traces of its former glory when illustrious characters like “Lepke” and “Gurrah,” the leaders of Murder Inc., a Jewish appendage to the Mafia, made their headquarters there. The school was located in a converted bank building. The faded elegance of the structure was still visible in the marble floors and bronze gates of the first floor where the bank’s public business had once been transacted. The marble floor was usually dirty. The walls were covered with dust and cobwebs, adding a touch of decay to yesteryear’s elegance. Nothing had been done to spruce up the building. This was partly due to the perennial financial crises which made it seem as if the yeshiva was always on the brink of being permanently closed. There was also a deeper reason for the ugliness: Orthodox Judaism has always been deeply distrustful of sensuous spontaneity. A tradition that prohibits men from shaking hands with women cannot be expected to encourage the growth of a rich aesthetic sensibility. This world is a stage upon which God’s law is to be obeyed; undue attention to beauty would be a waste of time better spent in the study of that law. God was to be adored as the cobwebs multiplied.

The most important room in the yeshiva was located on one of the upper floors. It too lacked adornment save for a small ark containing the scrolls of the Torah. This room, the beth ha-midrash, served as both synagogue and study hall. Over a hundred students could usually be found sitting around tables in small groups. There were also some older men, the rebbes, interspersed among them. The room was very noisy. At every table students were engaged in reciting aloud the text of a Talmudic tractate or discussing its meaning.

In spite of the din and the drabness, the age-old tradition of Talmudic study was preserved intact. The rebbes at Chaim Berlin were largely ignorant of contemporary historical scholarship which is capable of critically examining the Talmudic literature and arriving at an increasingly accurate picture of the men and the societies that produced the successive layers of that literature. Nevertheless, the Talmud was a living document for them. Chaim Berlin may have offended my aesthetic sensibility; it moved me morally and religiously. There was an authenticity manifest in the lives of its best teachers which seemed to be radically different from anything I had seen elsewhere in American Judaism. The very traditionalism of the institution added stature to the men who taught there. They transcended the lower-middle-class drabness of their surroundings by living according to a code that was the distillation of the wisdom and experience of a hundred generations of their people. They were proud of the fact that it was their vocation to hand that tradition down to yet another generation. There was also the factor of Auschwitz although it was seldom mentioned. Chaim Berlin was one of the very few yeshivoth that had survived the Holocaust. The great yeshivoth of Europe were no more. Israel was about to face its life-and-death struggle for independence. In 1947 there was the distinct possibility that the survival of traditional Judaism rested with a handful of impoverished institutions, neglected by the prosperous American Jewish mainstreams, institutions such as Chaim Berlin and Mesivta Torah Va-Daath in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn.

Rav Yitzchok Hutner was a somewhat rotund, hearty man with dark hair and a beard. He had an immensely powerful personality, which was evident in the physical power of his handshake, as well as in a certain electric air about his presence. It would be unfair to say that his personality dominated those around him. That would convey an image that would not be entirely accurate. Yet, he did dominate as an exceptionally sensitive medieval father confessor might have influenced those who habitually turned to him for counsel and absolution. As were so many Talmudists of distinction, Rav Hutner was a Lithuanian Jew. He had studied at the Slobodka Yeshiva, one of Europe’s greatest centers of rabbinic learning. Unlike Samuel Atlas of the Hebrew Union College and Louis Ginzberg of the Jewish Theological Seminary, Hutner had sought no Western-style Ph.D. He was not interested in being a modern Orthodox Jew. His religious cosmos had never suffered the cultural and theological lesions the men who had gone to German universities had had to endure. Nevertheless, Hutner was no obscurantist. He was an immensely perceptive intuitive psychologist who maintained his moral authority over his disciples long after they left the yeshiva to work in Orthodox Jewish day schools and to serve as Orthodox rabbis in the larger and more compromised American Jewish community.

Rav Hutner’s school had as one of its functions the training of rabbis. Yet, the man did whatever he could to dissuade those he ordained from accepting even the most Orthodox pulpits.

“It is a mitzvah, a service of God, to keep the laws of the Torah,” he would say, “it is no mitzvah to become a rabbi of a synagogue.”

On other occasions he would say, “Judaism needs good baalay batim, religiously committed laymen (literally, “masters of households”); it doesn’t need more rabbis.”

He understood that it would be impossible even for his disciples not to make compromises once they made a profession out of their learning. Such compromises were unpardonable breaches of God’s law. He had no desire to see the initial stages of corruption set in the moment a man was hired by a synagogue. He thought of schools that train pulpit rabbis as trade schools. In his eyes, they were necessary evils, but they were also a waste of time for men of spiritual integrity.

At times, he expressed a kind of admiration for honest unbelievers which he withheld from those who maintained a compromise position. He told of one great rabbi who was asked, “Rabbi, why is it that the ‘lefties’ seem to prosper so much more than the `righties’?”

“Because emet [truth] is on their side.”

“How can that be, rabbi? How can truth be on the side of those who keep none of the commandments?”

“Because it is emet that they are ‘lefties’ and it is not emet that we are ‘righties.’ If it were, we would prosper, not they.”

Although I had been at the Jewish Theological Seminary for only a short time, I had come to see that that institution was as compromised as had been the Hebrew Union College. It is difficult for me to describe the impact Rav Hutner had upon me. Apparently, I needed a father-surrogate whom I could respect. Such men were rare at both the college and the Seminary. Hutner was a strong, perceptive person in his own right. He also carried with him the moral authority of thousands of years of tradition. He was certainly the most authoritative yet humane interpreter of what I regarded as God’s law I had ever met. Twenty-five years later, a part of me still regrets that I could not permanently remain his disciple. I know that he cannot be happy with the direction my career has taken. Nevertheless, of all my religious teachers, I retain the greatest respect for him.

When I first met Hutner, I told him about my nonreligious upbringing, my encounters with both Unitarianism and Reform and my decision to enter the Jewish Theological Seminary and become a Conservative rabbi. He offered no objection to the plan. He told me that he would think about what I needed to “learn Torah.” He asked me to return in a week. When I returned, he said that Rav Asher Zimmerman, one of the teachers at the yeshiva was willing to give me an hour’s private instruction five days a week. I would spend every weekday morning in the beth ha-midrash sitting at the Rav Asher’s study table. At some point during the morning, he would instruct me in a section of the Talmud. I would then review the section until I knew it well. If I had questions, I could ask Rav Asher. My teacher would only charge me a token seven dollars a week. He had chosen Rav Asher partly because of his great learning and piety and partly because his native language was English. Instruction in Talmud was normally given in Yiddish in both Eastern Europe and in American Orthodox rabbinical schools. I knew no Yiddish. It was important that my teacher be able to express himself with precision in English. Most of the rebbes could speak English but they had no experience in teaching or interpreting the Talmud in English.

Rav Asher was a thin man of medium height in his middle thirties, with a mustache and balding brown hair. He was American-born, but his parents had sent him to pre-war Poland to the Mirer Yeshiva for his rabbinical training. He had never had any secular schooling. He was regarded with great reverence by the students. He lived in the most Orthodox section of Williamsburg with his wife and their small children. He was an extremely patient teacher who was determined not only to introduce, me to the study of the Talmud but to win me over to “a life of Torah.”

Rav Asher had never seen a movie. He believed movies were a waste of time that could be best spent on Torah. He never looked at picture magazines. He regarded the relatively modest pin-ups carried by Life and Look as unduly unclothed. Study of the Torah and observance of its commandments were alone worthy enterprises for him. He had no time for games or physical exercise. There was for him only one way to spend one’s days. If he possessed any religious doubts, they were so deeply hidden that he was entirely unaware of them. One day shortly after the Israeli War of Independence he told me that he had heard from a friend in Israel the real reason for Israel’s victory over Egypt near Beer Sheba, Abraham the patriarch’s place of settlement in ancient Palestine.

“It was dark,” Rav Asher said. “The patrol had lost its way. The men were in danger of getting lost in the desert. When things seemed at their worst, an old man with a white beard suddenly appeared out of nowhere and showed the patrol an unknown path. The Israelis were able to ambush a much larger Egyptian force. When the battle was over they looked for the old man, but he had disappeared. Somehow, they all knew who he was. He was Abraham avinu, Father Abraham, come to rescue his children.”

Rav Asher admitted that the old man’s appearance could have been imaginary, but he indicated that he didn’t really think so. He believed in the miracle as he believed with full faith in all of the miracles told in the Bible.

Once we got to know each other, Rav Asher would often invite Ellen and me to spend the Sabbath in Williamsburg with his family. We were moved by the experience. Rav Asher excelled in one of the most demanding of scholarly disciplines, Talmudic studies. At the same time, there was an unself-conscious ease about his life as an Orthodox Jew which both Ellen and I respected and to which we aspired.

I regarded Rav Asher as the polar opposite of Ezra Band. In spite of his Orthodox ordination, Band seemed to be part of the Auschwitz-world I was attempting to escape. Band’s instruction had the effect of intensifying my own Sabbatian temptations. Rav Asher calmed me. He gave me the assurance that the life of moral and religious certitude to which I aspired was within my grasp.

When I began lessons with Rav Asher, I kept the dietary laws and faithfully offered prayer three times a day, as is customary among traditional Jews. Our new way of life was infused with confidence and enthusiasm. Ellen and I saw ourselves as having miraculously escaped from both the secular world and corrupt middle-class Judaism. Our new life gave us a commitment that solidified the problematic bond between us. We were partners in this spiritual venture. Traditional Judaism reserves the term, baal teshuvah, for one who repents his old life and begins to live in accordance with God’s law. We were assured that there was greater rejoicing on high for a baal teshuvah than for one who had never tasted the temptations of a life without Torah. We enjoyed the attentions we received from our new friends so much that we were often tempted to overemphasize the miseries of our old life and how wonderful it was that we had found the better way.

As the months passed, my respect for Orthodoxy and my questions about Conservative Judaism grew. Conservative Judaism began to seem even more objectionable than Reform. Reform Judaism made no pretense that it had kept the tradition intact. Only those who had already broken with tradition would be attracted by it. Perhaps Reform might help them to preserve their ethnic if not their religious identity. Conservative Judaism seemed like ersatz Orthodoxy. It often gave the appearance of retaining the ethos and the authentic liturgy of the Orthodox synagogue. In reality, there were vast areas of belief and practice in which it had compromised itself.

Not surprisingly, I was most disturbed by Conservative Judaism’s compromises with Orthodoxy’s insistence that any suggestion of an erotic element in worship be repressed. In traditional synagogues not only are men and women seated separately, but women are also required to sit behind a mehitzah, a partition. Women may not officiate in any capacity at services and a woman’s voice, especially in song, is regarded as a seductive incitement. In 1947 many new synagogues were beginning to spring up that permitted mixed seating. The founders of these synagogues were convinced that there was little difference between Conservative and Orthodox Judaism, save for the fact that “families could sit together.” They argued that the mixed seating would lead to a more meaningful religious life for the entire family, because all could worship as a unit. I was convinced that Orthodoxy’s insistence on the separation of the sexes and its repression of the erotic was based upon a profound religious and psychological intuition. I felt very much like those Roman Catholic conservatives who opposed the reforms of Vatican II. It was their conviction that, were even one crack to appear in the sacred fortress which held back the onslaughts of secularity and relativism, the whole structure would collapse. Mankind would then be condemned to an existence in which neither moral nor spiritual authority retained even the slightest hold. I was fearful that wherever Conservative Judaism abandoned Orthodoxy’s insistence on strict sexual definition and discipline, the worst excesses of Sabbatianism would eventually reassert themselves. This fear was, of course, reinforced by the knowledge of how potent my own Sabbatian fantasies continued to be. It was almost as if I were crying out, “Give me a straitjacket, O Lord, lest I outdo Sabbatai Zevi …”

Neither Reform nor Conservative Judaism could serve as my spiritual straitjacket. Orthodoxy seemed to be the only possible defense against a life of moral, spiritual, and, perhaps, psychological chaos.

Once again, I was faced with a crisis. I was admitted to the Rabbinical School of the Jewish Theological Seminary in September 1948. Classes were to begin after the fall sequence of holidays, Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, and the eight days of Sukkoth. I no longer wanted to enter the Seminary. I wanted to become an Orthodox rabbi. I saw myself as defending order against chaos by saving assimilated Jews like myself from the spiritual perils of the contemporary world. It was useless, I thought, to fight the world’s Nazis unless one were purified of all taint of that which led to Nazism in one’s own soul. Only perfect fidelity to God’s revelation could lead to such a purification. To become a Conservative rabbi now seemed tantamount to rebellion against God. At the core of my being I still did not believe in such a God. Nevertheless, my fright compelled me to hearken with ever greater scrupulosity to his revelation. It seemed as if I had only one remaining alternative, to become an Orthodox rabbi.

There were, however, difficulties. I was aware of the fact that those who knew me tended to regard my changes in religious commitment as evidence of acute instability. On the surface I refused to let this get to me. But, at a deeper level I was profoundly disturbed by the recognition that there was much justice in that opinion. Another consideration was that Ellen was pregnant. There was a limit to the financial and emotional insecurity I could inflict upon her. It was doubtful whether I could complete the studies at Chaim Berlin in an endurable period. It would be difficult enough to become a Conservative rabbi. I had the intellectual ability to become an Orthodox rabbi, but the cost in time and emotion would be even greater.

Orthodoxy seemed to be the only possible defense against a life of moral, spiritual, and, perhaps, psychological chaos.

Neither Rav Hutner nor Rav Asher Zimmerman encouraged me. They indicated that I would be welcome at Chaim Berlin, but Rav Hutner suggested that the wiser course would be for me to find a nonreligious profession while continuing to live as an Orthodox Jew. In retrospect, this would have been the most practical solution had I been primarily interested in obeying God’s commandments. I did not perceive that my hankering for the priest’s magic remained greater than my desire to obey God. From the time I wanted to be a Unitarian minister my interest in an omnipotent profession never faltered. Even my flirtation with the academic study of philosophy was no exception. If I could not serve as a priest, I could at least possess the saving knowledge of the mystery of existence. Rav Hutner’s suggestion that I serve God as a mere layman was clearly unacceptable.

Ezra Band was the only one who encouraged me to leave the Seminary. He reinforced my conviction that the Seminary represented the kind of compromises that would ultimately lead to a contemporary form of Sabbatianism. He presented me with the hope that I might be a defender of civilization itself were I to make the proper decision. He warned me that, were I to remain at the Seminary I would be worse than the most contemptible bourgeois because I understood what was spiritually at stake in choosing the compromises of Conservative Judaism. Most people simply did what they had to in order to survive in a corrupt world. If I went to the Seminary, I might cover myself with the title of rabbi, but, in reality, I would be a cheating, despicable merchant. My rabbinic office would at best be a pretense, at worst a contemptible fraud. If that was what I wanted, he argued, why waste four or five years at the Seminary? It would be far cleaner to go into business and make my way in the secular world.

Band almost convinced me. One evening while Ellen was in Cincinnati with her parents, Band and I decided to go over to the Seminary dormitory and tell Wolfe and Sam the “good news” of my latest decision. Band was almost manic in his enthusiasm. He rolled his eyes and gesticulated energetically as he said, “Isn’t it wonderful, he’s going to leave this terrible place and go to Chaim Berlin!”

“If it’s so bad,” Wolfe asked him, “why do you stay?”

“I’ll leave as soon as I can. I have to make my plans carefully,” Band answered. “But think of the drama. A man with Rubenstein’s background leaving all this corruption and compromise to go to the Mesivta!”

“Whose drama,” Wolfe calmly asked, “yours or his? You goad him into leaving while you stay. He’s got a pregnant wife. He’s made enough changes. Do you want to wreck him?”

As Wolfe spoke, I began to see Ezra as a peculiar kind of Mephistopheles. Faust was enticed with the lure of Gretchen, Walpurgisnacht, and Helen of Troy. Band was seducing me with the promise of an impossible ideological purity, made all the more questionable by his own refusal to take the same path. An animal instinct warned me that life was superior to ideology, that sooner or later I would be compelled to join the human race and make some compromises in order to keep myself and my family intact. With his fundamentally sympathetic knowledge of Orthodoxy, Wolfe was protecting me from myself.

When Ezra saw that the drama was not going to take place, he cooled toward me immediately. He became extremely contemptuous. He said very little to me thereafter but at each of our subsequent meetings it was as if he were saying: “You may fool the rest of the people around here, but you can’t fool me. I know you for the contemptible, pretentious bourgeois you are. I prefer an honest cheat to someone like you.”

Ezra’s contempt was the counterpart of my own self-contempt. His disdain for bourgeois Judaism was reminiscent of my mother’s. His disapproval was reinforced by echoes of an infinitely more potent and archaic source of authority and values. During the time I was a student at the Jewish Theological Seminary, I never ceased to despise myself for having permitted practical considerations from interfering with the purity of my resolve. I was convinced that my decision to become a Conservative rabbi was an offense against God. I did not feel less guilty because I did not really believe in the God I was offending! After ordination I had again to face Ezra at Harvard. He spent several years there as a postdoctoral fellow. Whenever we met, he would reinforce my negative feelings about myself for having become a Conservative rabbi and for having contaminated myself by daily association with ordinary middle-class Jews.

Partly in order to ward off both his accusations and my own, I resolved to be as strictly traditional as I possibly could. Life may have forced me to become a Conservative rabbi, I reasoned, but nothing prevented me from living a thoroughly Orthodox personal life. From the moment I entered the Seminary until I was helped by psychoanalysis to regard myself with a less anguished vision, I experienced a pervasive and never-ending sense of uncleanliness and moral pollution about the kind of rabbinic vocation I had chosen.

The crisis about my decision to enter the Seminary was only one side of my encounter with Orthodox Judaism. Other aspects of the encounter had an even more profound effect on Ellen and me. Almost immediately after I began to study with Rav Asher and long before my crisis about entering the Seminary, Rav Asher raised the question of whether Ellen and I would observe the laws of taharat ha-mishpaljah, the laws of family purity. Orthodox Jews follow the biblical injunction that, seven days after the menstrual period, a woman must be purified by full immersion in a fount of “living waters” before she can again become sexually available to her husband. Reform Judaism has long regarded such taboos as primitive superstitions of no relevance to enlightened Jews in the twentieth century. Conservative Jews have been embarrassed by the subject. In spite of the claim that their movement was essentially faithful to the observance of Jewish law, they have been as indifferent as Reform Jews to the laws of family purity.

When Rav Asher raised the issue, I was unenthusiastic about the prospect of Ellen going to the mikveh, the ritual bath, every month. I responded politely but dismissed the suggestion. Nevertheless, a seed had been planted. I felt there was a certain logic to Orthodox Judaism’s insistence that God really cared about the conditions under which I made love to my wife. The Orthodox insistence that marital sex had to be minutely regulated seemed in some respects less repressive than liberal Judaism’s attitude, which was to leave the individual entirely on his own resources in dealing with the complex emotions which attend both menstruation and sexual intercourse. Fear of menstrual blood is one of the most widely attested masculine responses to the mystery of femininity in practically every culture. No relationship is as fraught with emotion, both pleasurable and anxious, as the sexual relationship. It soon became apparent to me that part of Orthodox Judaism’s fundamental integrity was its ability to give these complex realities an ordered place within the spiritual life of its adherents.

I resisted Rav Asher’s suggestion for a time, but my passion for ideological consistency impelled me to ever greater compliance with every aspect of God’s law. If God had given the commandments, who was I to decide which to obey and which to reject? There could be no lacunae in my religious practice. I reasoned that selective obedience was sinful. It also placed me in the very predicament I had sought to escape. If the final decision were mine, what, I asked myself, could prevent me from fulfilling the laws concerning prayer while at the same time indulging in adulterous excess? Sabbatai Zevi’s image never left me. The law could only give me the moral certitude I sought, were I to commit myself to it all the way.

I came to understand that there was in fact only one sin in biblical religion although it took many forms. That sin was disobedience. Every biblically ordained commandment became a test of my willingness to disobey myself, in order the better to obey God. It was not for me to question why God had commanded me to observe the laws of family purity. My task was to try to understand what God required of me, not why he had done so.

Ellen and I initially experienced our new commitment as an enormous spiritual gain. Just as we were partners in forsaking our former life in the matter of prayer, study, and diet, we were now partners in forsaking our old sexual ways. Whatever ambivalence existed between us in this area was seemingly diminished. We now felt that we were delighting in the joys of the bridegroom and the bride in a way that was pleasing in the sight of the Lord. There were moments when it almost seemed as if he were present as a third party at our celebrations of love. Our actual love-making achieved a kind of chastity. For the first time, I was free of all sense of guilt in my sexual relations.

Observance of taharat ha-mishpahah further intensified our disdain for bourgeois Judaism and our own pride that we were no longer a part of it. This was, of course, before I faced the crisis of whether I would become a Conservative or an Orthodox rabbi. I came to regard most of the leaders of Conservative Judaism as insincere men who pretended to a piety they did not possess. At the Seminary, I heard a great deal about Conservative Judaism’s fidelity to Jewish law, but whenever I asked about taharat ha-mishpahah, I was met by silence and embarrassment. Understandably, some people at the Seminary began to regard me as an eccentric given to extreme positions. In retrospect, it would seem that whatever I gained by fidelity to the law was offset by a heightened sense of pride and a kind of spiritual arrogance that I was somehow less compromised and less evasive in my religious commitments than most of those I knew. There was little modesty in my position. My “vocation for the summit” had not been altered by my “conversion.” I now sought to feel that I was better than others by virtue of the greater logic and consistency of my spiritual position.

After I had begun to observe the laws of taharat ha-mishpahah, there remained a glaring example of my unwillingness fully to obey God’s commandments. The first positive commandment given by God to Adam and his progeny was to be fruitful and multiply, yet when Ellen and I made love, she used a birth control device. Both of us felt that it would be impossible for us to have children for years to come. Whether I entered the Seminary or Chaim Berlin the following fall, it would be years before I could be ordained and get a full-time job. If Ellen and I were to have any degree of economic security, it was imperative that we both work.

Having children as I embarked once again on a career as a full-time student was utterly impractical. Yet, I could not ignore the commandment to be fruitful and multiply. I was again faced with the same problem: Who was I to decide which commandments to obey? I again asked myself whether I had any right to permit economic considerations to compromise my religious commitments.

Beyond the practical considerations, there was the simple but largely unrecognized fact that neither Ellen nor I were emotionally ready to become parents. We required a greater measure of psychological, if not economic, stability. The turbulence of our lives was simply too (great to permit us fully to assume the parental role. Yet in spite of the practical problems, the decision to have children was inevitable. I was earning two thousand dollars a year as a Hebrew teacher. My income was insufficient for a family life of even the most disciplined frugality, and Ellen and I were given to impulse spending. Nevertheless, I told Rav Hutner that Ellen and I would cease to violate the commandment to be fruitful and multiply.

I was very frightened as I contemplated the prospect of becoming a father. Ellen went to the mikveh for ritual purification after her menstrual period. When she returned home, there was an inner glow about her. She seemed more beautiful than ever. We made love without reserve and with a warmth and a wholeness we had never before experienced ever on our wedding night. In spite of our fears, we wanted a child that night.

I have always felt that my oldest son was conceived that evening. Within a short time we learned that Ellen was pregnant. It was the best time of our marriage. We were apprehensive about money; we were peculiarly unfinished emotionally, but for a short time we felt that there was a profound rightness about what we were doing. In the midst of a world of war, death, and unbelief, we had given ourselves wholly over to a greater power; we had given ourselves to the power of life. In spite of the harsh difficulties I was to face as a father, I have never ceased to be grateful to Rav Hutner for encouraging me when he did.

Unfortunately, there was little certainty that life would indeed triumph. In her fifth month Ellen began to stain badly. It looked very much as if she might miscarry. Her obstetrician told her that it was imperative that she remain off her feet and have nursing care at all times if the child was to be born at all. We were totally unprepared for this catastrophic turn of events. We had saved up enough money to pay for the doctor and a normal hospital stay, but no more. Fortunately, by this time I had entered the Seminary’s Rabbinical School and we were able to receive help from emergency funds made available to us by the Seminary. On April 19, 1949, she gave birth to a very healthy son. Thousands of years ago, scripture records that God spoke unto Abraham:

As for you, you shall keep My covenant, you and your offspring to come, throughout the ages. Such shall be the covenant, which you shall keep, between Me and you and your offspring to follow: every male among you shall be circumcised. You shall circumcise the flesh of your foreskin … At the age of eight days, every male among you throughout the generations shall be circumcised. …

As it had been for over a hundred generations, so it was with Aaron. According to Jewish tradition, it is the duty of the father to circumcise his own son. Since few fathers have either the skill or the calm to carry out so delicate an operation, it is customarily performed by a mohel, one skilled in the techniques of the operation and possessed of a reputation for religious rectitude. Aaron received the sign of the covenant at a ceremony conducted in accordance with strict Orthodox tradition. His body and his psyche were altered by an archaic rite which linked father and son in an unbreakable bond to Israel’s primal antiquity. Ellen and I had been carried along by the supra-personal force of life itself when Aaron was conceived. At his circumcision, Aaron and I were swept along by an ancestral culture which enveloped the entire family. Aaron was thousands of years old the day he was born.

There was a palpable air of tension and anxiety at the ancient rite as the mohel took out his surgical instruments and prepared to remove the child’s foreskin.

What if the instrument slips? I thought.

Will it hurt my baby? I wondered. Did I perhaps want it to hurt my baby? I rejoiced in the birth of a son, but Ellen’s attentions would now be divided. Where there had been two, there would now be three. Was there some corner of my being in which I wanted the knife to slip? Could I possibly be one of the castrating fathers psychoanalysts have written about? After all, those psychoanalysts were themselves mostly Jewish. Perhaps they knew something I didn’t know. There was something indelibly primitive about the ceremony, yet the participants were highly educated men, rabbis, professors from a rabbinical school, and rabbinical students. In what century was the ceremony really taking place? Was I with Father Abraham in the Negev or in America?

I came to understand that there was in fact only one sin in biblical religion although it took many forms. That sin was disobedience.

I was assured by the mohel that the ceremony was performed before the child developed any localized sense of pain.

“It’s nothing,” he said, “don’t worry. It’ll all be over in a few moments.” But it wasn’t “nothing” and it wouldn’t be over as long as Aaron lived. Something uncanny had taken place. The circumcision was the first act in which I had asserted my unchallenged authority as a father over my first born son. For seven days the child had been lovingly tended by his mother. On the eighth day, he had been abruptly taken away from the woman’s world and forcibly introduced into the world of men! and the service of a masculine deity. His diffused ego was given a masculine focus far earlier than would have been the case had nature been permitted to take its course. Culture had triumphed over nature; the city over the countryside in that eight-day-old infant.

His body had been fundamentally altered by circumcision; so too had his psyche. Can one be changed without the other? Whenever he thought of that archaic injury in later life, he would always wonder whether there was worse to come. In addition, I had put my mark on his masculine organ. I had no doubt that he was my child. Nevertheless, I had claimed him as my own as Father Abraham had once claimed Isaac, in spite of Sara’s questionable night visits with Pharaoh and Abimelech, king of the Philistines.

On the eighth day … Aaron hadn’t been asked. There would come a time, perhaps when he was seven or eight, when he would do the asking. I did when my brother was circumcised. Perhaps his thoughts would be similar to the ones I had. I remember thinking to myself: Is this what Daddy did to me when I was little? What would have happened if the knife had slipped? Suppose I’m really bad, what would Daddy do to me?

There are those who claim that circumcision reduces masculine sensitivity and so dampens passion that a circumcised man can never let himself go as completely as an uncircumcised man. I have no scientific way of evaluating that suggestion but it ought not to be rejected too hastily. The acculturation process within Judaism has the effect of limiting the physical and emotional hold a woman can have over a man. That process begins on the eighth day.

The book of Exodus contains traces of an even more archaic rite practiced by fathers upon their sons on the eighth day in the almost forgotten reaches of Israel’s pagan antiquity. God is depicted as demanding:

Sanctify unto me all the first-born, whatever opens the womb among the Israelites, both of men and of beast; it is mine.

Most scholars agree that the earliest sanctification of the first born of both men and animals involved the setting aside of the first born as sacrificial offerings. This is stated almost explicitly in Exodus 22:28,29:

The first born of your sons you shall give to me. You shall do likewise with your oxen and your sheep; seven days it shall be with its dam; on the eighth day you shall give it to me.

Every year on Rosh Hashanah, the lesson from scripture retells the story of Father Abraham’s ascent to Mount Moriah to offer his first born son by Sara as a “burnt offering” unto the Lord. As Abraham raised his knife to slaughter the child, the dire necessity was miraculously averted. A ram was provided by God in place of the child. Orthodox Judaism has never permitted the memory of the archaic sacrificial slaughter of the first born entirely to disappear. Every Jewish father is required to “redeem” his first born son on the “thirty first day of his birth” in a ceremony known as the pidyon ha-ben or Redemption of the First-born Son.

On Aaron’s 31st day, my family joined with a small group of rabbinical students and teachers at our apartment in New York to take part in Aaron’s pidyon ha-ben. On the surface, the occasion was a joyous family celebration of the happy addition to its circle. Customary Jewish delicacies were served. Beneath the surface something at odds with all pretense to rationality and modernity took place. Aaron was brought into the room on a cradle of pillows placed upon a silver tray. I then handed him over to a cohen, a hereditary priest, a man who could by family tradition trace his lineage back to the Israelite priesthood of biblical times. As I presented Aaron to the cohen, I repeated an ancient formula:

This, my first born son, is the first-born of his mother, and the Holy One, blessed be He, has commanded that he be redeemed as it is said: “And those that are to be redeemed of them from a month old shalt thou redeem, according to thine estimation, for the money of five shekels after the shekel of the Sanctuary …” and it is said:

“Sanctify unto me all the first-born, of man and of beast: It is mine.”

I took out five silver dollars, the symbolic equivalent of the biblical shekels and placed the money in front of the cohen. The cohen asked me in accordance with the prescribed ritual:

Would you rather give your first born son, the first born of his mother, or would you rather redeem him for the five selaim [shekels] which you are bound to give according to the Torah?

I had rehearsed my part. I knew what I was required to respond:

I would rather redeem him. Here, you have the value of his redemption which I am bound to give according to the Torah.

However, as I recited the formula I asked myself: What am I really redeeming him from? What would the cohen do if I told him I would rather keep the money? The fleeting thought was immediately suppressed. At the time, I had no conscious awareness that I might have been tempted to alter the customary ritual. Years later I found myself fascinated by this strange and awesome ritual. On one occasion, as I permitted my imagination to flow freely, the following scenario was enacted in my fantasy:

Richard: I want my money. God can have the boy.

Cohen: You’ve no right to keep the money. The Torah has commanded you to give up the money and redeem your son.

Richard: Redeem him from what?

Cohen: I don’t know ... just redeem him.

Richard: That’s nonsense. You know as well as I do what I’m supposed to redeem him from.

Cohen: Maybe so, but that’s all the more reason for you to give me the money. I’m not a bloodthirsty man.

Richard: You don’t have a choice. The Torah also commands me to give my first born son to God. You’re God’s holy priest; take him for God.

Cohen: I can’t. My wife and I have our own children. I don’t need yours.

Richard: I’m not giving him to you. I’m giving him to God through you. You know what God really wants. Stop playing games. Do your duty as a priest.

Cohen: I know what God doesn’t want. Nobody in three thousand years has behaved the way you have at one of these ceremonies. This thing was settled by Father Abraham. Haven’t you ever gone to the synagogue on Rosh Hashanah? Haven’t you ever heard a rabbi tell you God didn’t want the life of the child. He wanted the ram instead. Your money is just like Isaac’s ram. God is permitting you to give your money and keep your child.

Richard: I don’t need him. He’ll only get in the way. It’s hard enough taking care of Ellen. Besides, she’ll give him more attention than me. I’m not ready to be a father yet. I want to be a great scholar, not an ordinary rabbi. How can I be a great scholar and support a family? You take him and give him to God. What is between you and God is none of my business. Just take him. I’ll keep the money.

None of this outrageous fantasy consciously entered my mind during the ritual. Nevertheless, there is a dark side to my nature which I can more easily acknowledge and manage today than I could then. There is one detail which suggests that more may have been going on beneath the surface than I was prepared to face: Aaron was not my first born son’s first name. It was his middle name. Neither he nor I have ever liked his real first name. Aaron’s suppressed first name is Isaac.

In the actual ceremony, after my declaration that I preferred retaining my son rather than my money, the cohen took the money and handed my Aaron back to me, saying,

This [the money] instead of that [the child]; this in exchange for that; this in remission of that. May this child enter into life, into [obedience of] the Torah and into the fear of Heaven …”

The child was now mine rather than God’s.

The fundamental purpose of the ceremony was both to acknowledge and to deflect whatever latent infanticidal tendencies I had toward my son. As Abraham had been commanded to circumcise his son, I had circumcised mine; as Abraham had offered up a surrogate for the life of his Isaac, I had done so for mine. For the moment Jewish tradition enabled me to believe that I had exorcised my infanticidal tendencies. Within a short time, my own wife was to call me the murderer of my second son.

Shortly after Aaron’s pidyon ha-ben, Ellen and I were again faced with the religious issue which led to her first pregnancy: Could we disobey God’s first commandment? The question was more urgent this time because of my sense of guilt for having entered the Jewish Theological Seminary. The use of a birth control device would have been further proof that Ezra Band was right after all, that I was really a spiritual fraud. Nevertheless, if the pressure to have another child had intensified, so too had the practical obstacles. Ellen’s health had seriously deteriorated during pregnancy. She badly needed a respite before having a second child. Unfortunately, we were too dependent upon the need for ideological purity to be realistic. Ellen became pregnant again almost immediately. The pregnancy itself was without incident, but she was neither physically nor psychologically prepared for the ordeal that was to follow.

Nathaniel Ephraim Rubenstein was born in June 1950 in New York City. When Ellen returned from the hospital, we had no resources with which to secure help for her. Our apartment was on the top floor of a building on Claremont Avenue in the Morningside Heights arch of New York. It was a small but pleasant apartment during most of the year. In the summer, it was infernally hot as the sun beat down upon the poorly insulated roof. Ellen had to care for the two infants alone under extremely difficult conditions. I felt that it was her job to take care of the babies and mine to study the Talmud. Regrettably, my attitude was by no means unique among traditional Jews. My help was less than adequate. Within a month she was close to emotional and physical collapse.

As her situation became desperate, Ellen’s parents intervened. She needed rest badly. They proposed that Ellen and the babies go to a mountain resort where she would not have to take care of the house and prepare meals. At the end of the summer it was arranged that she would visit Cincinnati, remaining there until after the Jewish holidays. I had been engaged to preach at the services of a congregation in Baltimore during Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. We would have had to have been separated for the Holy Days in any event.

Both Ellen and I were grateful for the van der Veens’ generous offer, but our newly found Orthodoxy created further difficulties. It was important that the resort be Orthodox in every detail. The food had to be kosher; the Sabbath strictly observed. We found an apparently suitable place through our Brooklyn friends. Unfortunately, everything about the place was strange and ugly to Ellen. The atmosphere, the people, the cuisine, the aesthetics were different from anything she was used to. It was one thing for us to attempt to live an Orthodox life together; it was very different for Ellen, worn out and discouraged as she was, to enter into so foreign a framework by herself.

I did not accompany Ellen to the country. Her father drove her and the children there. I gather from Ellen’s description that the rest turned out to be a horror story. She was worse off among strangers than she would have been at home doing her own chores. The Sabbaths were not the joyous occasions they were supposed to be. They were a form of torture she had to endure. According to Orthodox custom it is forbidden to turn lights on or off on the Sabbath. This was no problem in our apartment. We simply left a light burning in the living room. We opened the bedroom door when we needed light. We shut it when we wanted to sleep. At the resort Ellen and the children were confined to one dreary, ugly room which was illuminated by a naked light bulb that hung on a chain from the ceiling. It was a prison cell for her. There was no way to turn off the light without desecrating the Sabbath. Nathaniel’s feeding schedule compelled Ellen to get up several times during the night. Aaron would also cry occasionally. Ellen had little opportunity for the sleep she so desperately needed. When the boys ceased crying, the naked bulb became an instrument of torture compelling Ellen to remain awake. She kept faith with God’s commandments but her situation was becoming unendurable.

Things seemed to improve when she arrived in Cincinnati. The van der Veens provided her with day help. Lucy van der Veen took over many of the burdens Ellen had been carrying. Ellen seemed to get some of the rest she needed, although Nathaniel still required night feeding. Apparently, Nathaniel was especially disturbed the night before Yom Kippur. He cried a lot. Ellen got up several times to calm him down. The next morning Ellen found him lying on his stomach dead.

At the time Nathaniel was found I was preparing to conduct Yom Kippur services in Baltimore. It was the second year that the huge Baltimore congregation had invited me for the Holy Days. Dr. Rosenblatt, the rabbi, had sounded me out as to whether I might be interested in becoming assistant rabbi of the congregation after graduation. I had acquired a taste for preaching and the sense of power it gave me, especially on Israel’s most sacred days. If ever anything I did as an adult was in fulfillment of an infantile wish, it was my preaching. As I rode the Pennsylvania Railroad from New York to Baltimore, I was confident of my power to weave a spell over my listeners. I would control the way they saw me. I would control what they heard. I might not be God’s mouthpiece but I was the next best thing: I had the authority to stand before the community and interpret his word. I did not know that as I looked forward to the fulfillment of my childhood will to power, my own child lay dead in Cincinnati.

Officially, it was described as a crib death. We never really found out what happened. We might have learned the cause of death if there had been an autopsy. Both Rav Hutner and Professor Saul Lieberman, the professor of Talmud at the Seminary, counseled against an autopsy as contrary to Jewish law. The uncertainty was worse for Ellen than it was for me. Although she never said so to me, I have always had the feeling that she, like so many other mothers in the same situation, could never get over the feeling that she was somehow responsible for Nathaniel’s death. Our marriage began to deteriorate immediately. I could feel a sense of distance as we met in Cincinnati before the funeral. It was impossible for me to offer her any consolation. We were condemned to live with each other, but an icy wall now stood between us.

In the years that followed, our mutual anger would occasionally boil over. We would then say things we later wished we hadn’t. Whenever she became really angry with me she would scream: “You murderer, you killed your own son!” My wife’s hideous accusation hit the mark. I felt like a murderer. I had not given her the help she needed when she was strained beyond endurance. I had permitted her to go to a miserable Orthodox country place which only intensified her distress. I had left her alone with two infants at a time when her need for me was greatest. I was convinced that I had no time for anything but work, study, and prayer. The burden of the household rested with her. When that burden crashed down on the family with Nathaniel’s death, I felt there was justice in Ellen’s accusation. In my own eyes, I was an infanticide. I also found myself more deeply bound to Ellen by guilt than I had been by love. Divorce would have been unthinkable, but whatever warmth had formerly been present between us was fast dissolving. I felt I owed her an unnamable something. I had to make “it” up to her, yet I was incapable of spelling “it” out. I felt no need to atone for my son’s death before God; I felt every need to atone before Ellen. This need bound me to her long after we should have gone our separate ways.

In spite of our ordeal, I find no fault with Orthodox Judaism for what had occurred. Orthodox Judaism was never meant to be the private religious affirmation of two pathetically isolated young people, divorced from the customs and life-style of their parents and siblings. Mrs. Kelman could maintain a viable Orthodox household, as could Rav Hutner and Rav Asher Zimmerman, because their web of primary relationships had provided them with support systems for that kind of life from earliest childhood. Orthodox Judaism had always been a communal and a familial rather than an individual way of life. There is no place in Orthodox Judaism for the single one, magnificent in isolation, casting aside all familiar relationships the better to enjoy solitary intimacy and fellowship with God. Ellen and I had attempted to live an Orthodox life apart from our families and against the grain of the acculturation process which had given us our fundamental personalities.

After the funeral and the mourning period, as I have written elsewhere, there was only one man I wanted to see, Rav Hutner. He knew that something was very deeply wrong and tried to comfort me as he could. “I want you always to remember that Ribbono-shel-Olam, the Master of the Universe, never writes guarantees in this life,” he said. “I hope this doesn’t cause you to lose your emunah, your faith.”

I protested that nothing had changed. For over two years it seemed as if my fidelity to tradition had not been affected by the family catastrophe. Nevertheless, Rav Hutner’s original intuition was accurate. The change took its own time to surface. As the excruciating wound began to develop its overlay of scar tissue, I began to emerge from my numbness. I slowly became aware of the fact that my compulsive quest for consistency had led to the death of my son and had left my family life disrupted beyond almost all hope of repair.

Selection from Richard L. Rubenstein, “The End of the Law,” in Power Struggle (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974), adapted with permission of the author.

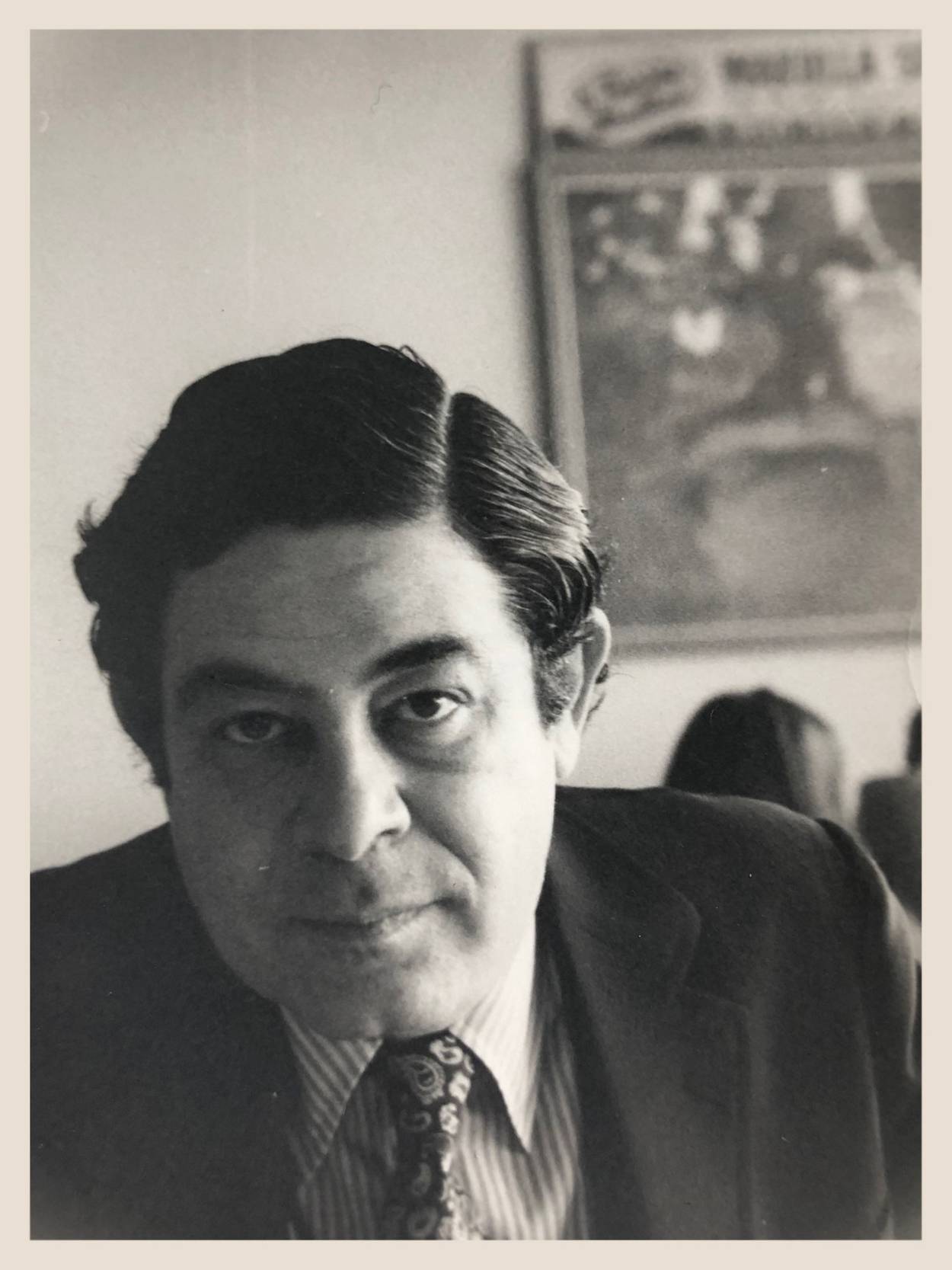

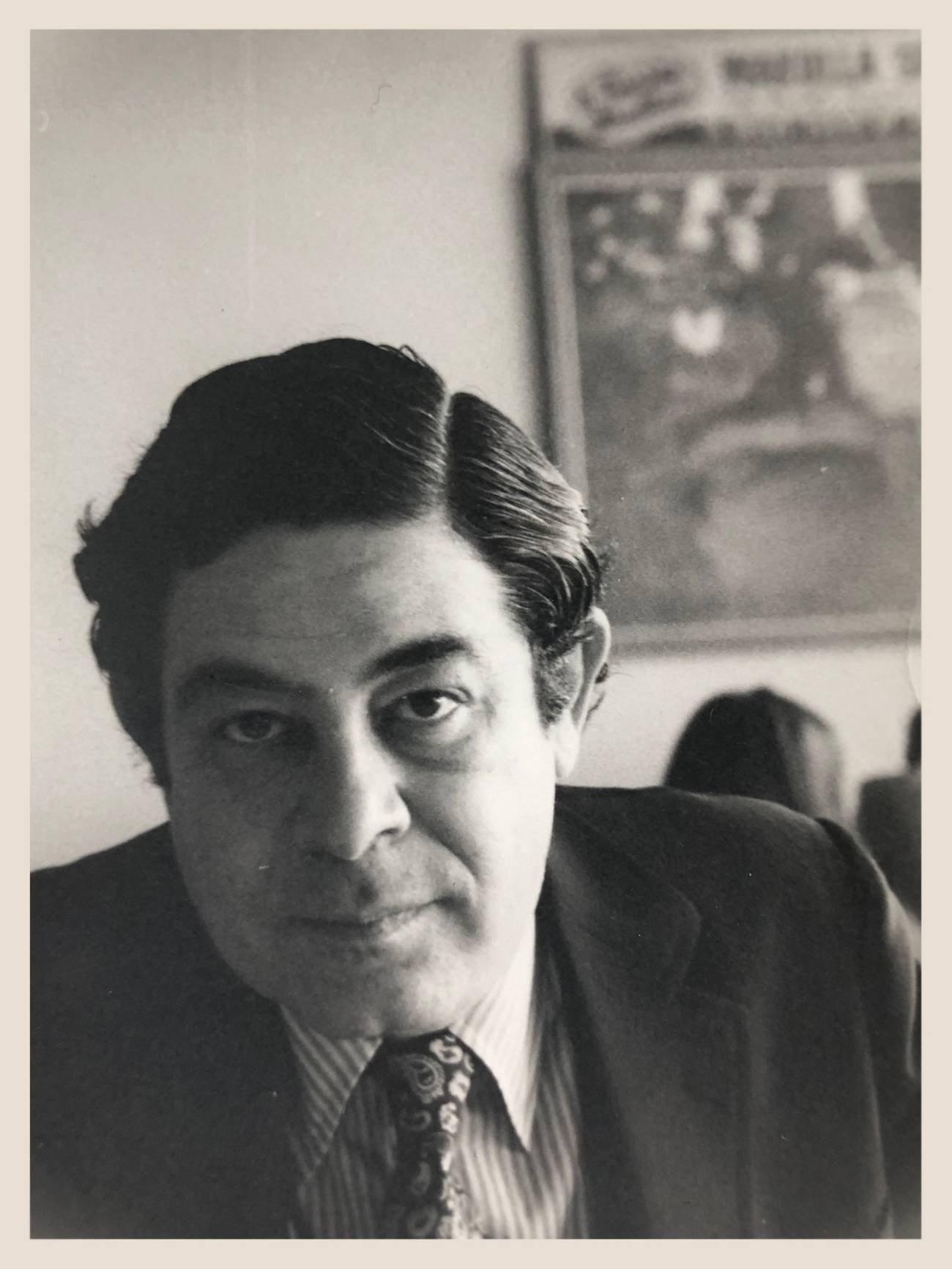

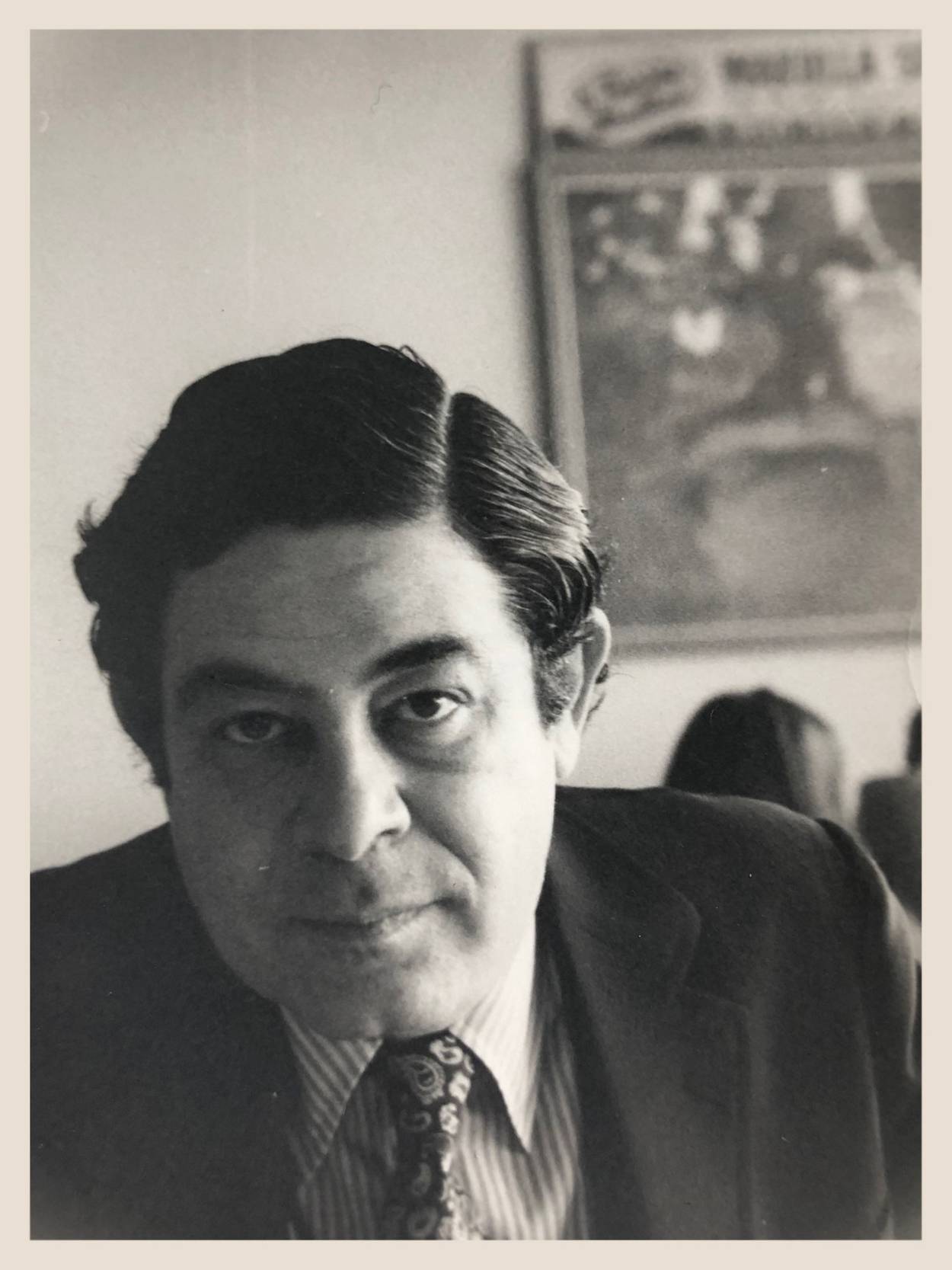

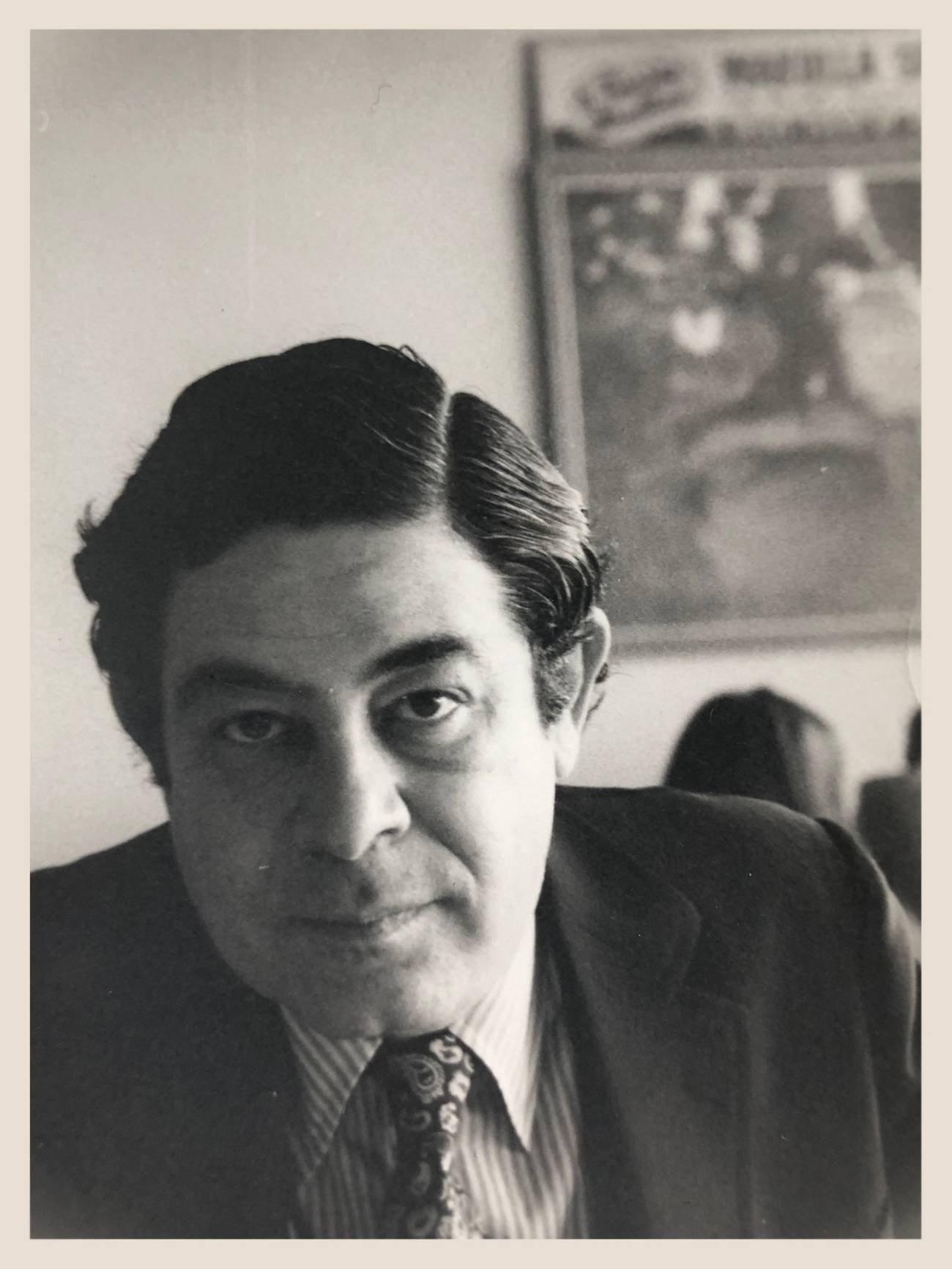

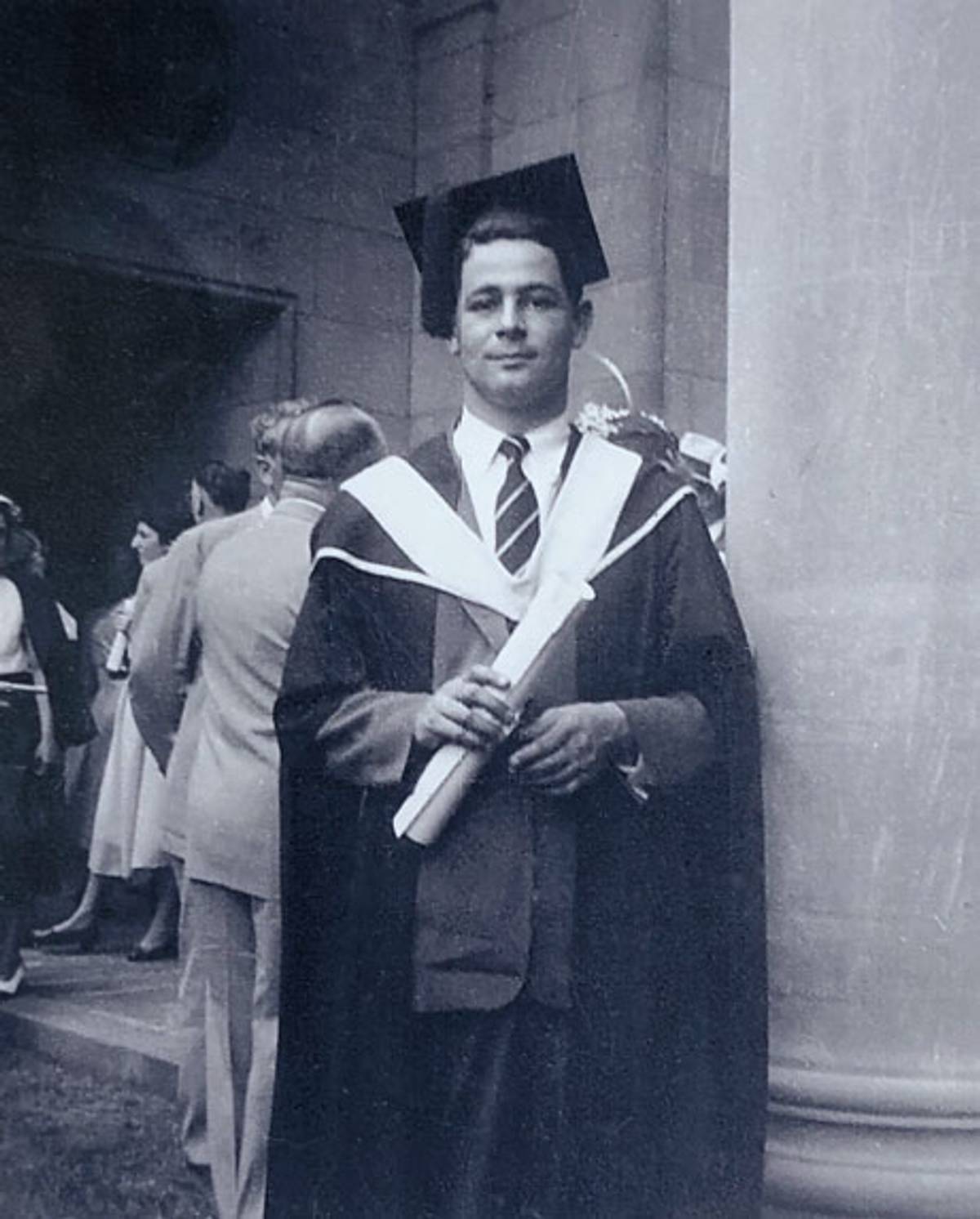

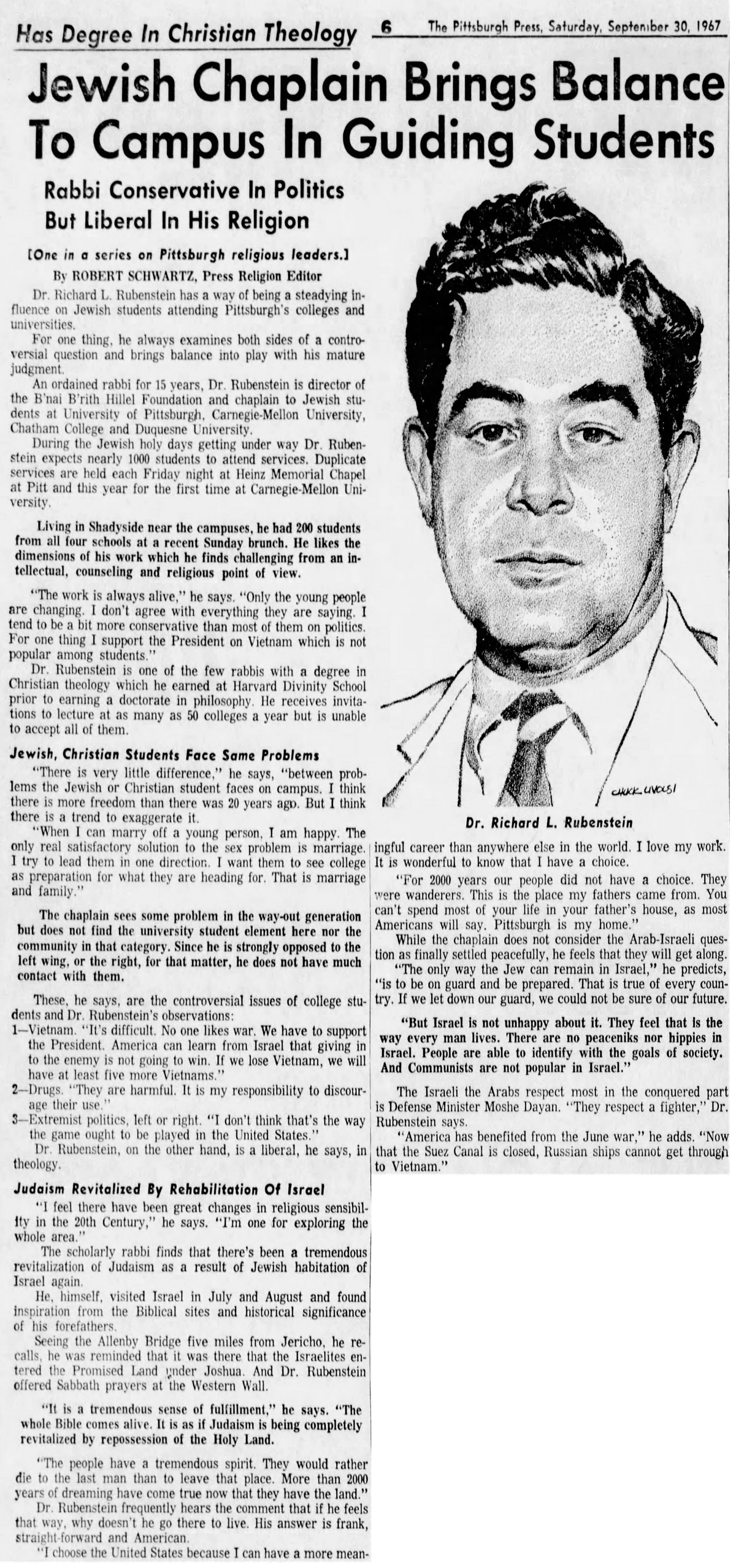

Richard L. Rubenstein, now nearly 97 years old, is a theologian, educator, and author. His first book, After Auschwitz: Radical Theology and Contemporary Judaism, initiated the contemporary debate on the meaning of the Holocaust in religious thought, both Jewish and Christian.