Safed Kabbalah and Renaissance Italy

How Lurianic mysticism made its way to Europe—and back to the Middle East

Attempting to establish an affinity between the prominent Safedian kabbalist Isaac Luria and the Renaissance Italian interest in kabbalah is not a simple historical task. It presupposes the possibility of documenting an acquaintance, fascination, or even an obsession on the part of kabbalists in the Land of Israel with the quandary sparked by the emergence of Christian kabbalah in Italy. That an awareness of the problems generated by this form of kabbalah was found in Jerusalem and Safed is obvious from quotations from R. Abraham ben Eliezer Halevi and, more important, from R. Moses Cordovero, Luria’s acknowledged master in kabbalah. The most eminent Christian kabbalist, William Postel, visited the Land of Israel, mainly Jerusalem, in 1549-1550, the beginning of the flowering of Cordovero and Safedian kabbalists, who could have learned about this visit. Cordovero was familiar with R. Moses Basola, himself an acquaintance of Postel from their Italian years. There is, therefore, little doubt that Safedian kabbalists knew of this visit, though Postel himself is never mentioned by any of them.

Even in a passage by one of the closest kabbalists to Luria, his disciple R. Hayyim Vital—too, a former student of Cordovero’s—we may discern interest in the transmission of secrets to Christians. In one of his dreams he committed to writing, he reported that he arrived in Rome, only to be arrested by the officials of the “Roman Caesar.” He is brought by soldiers to the “Caesar” and the latter orders the hall cleared, leaving them alone. Vital reports his dream as follows: “We were left by ourselves. I said to him: ‘On what grounds do you want to kill me? All of you are lost in your religions like blind men. For there is no truth but the Torah of Moses, and with it alone can exist no other truth.’ He (the Roman Caesar) replied: ‘I already know all this and so I sent for you. I know that you are the wisest and most skilled of men in the wisdom of truth. I, the most knowledgeable, want you to reveal to me some of the secrets of the Torah and the names of your blessed Lord, for I already recognized the truth.’ ... Then I told him a bit of the wisdom [of kabbalah] and I awoke.”

It is likely that “Caesar of Rome” refers to the pope, with whom at least two messianic figures, Abraham Abulafia and Solomon Molkho, sought an audience. Vital was certainly an aspirant to a messianic mission. There is no doubt from the context, where Vital portrays himself as dwelling in a cave with the paupers in Rome, that a messianic background informs the dream.

According to the above passage, the pope offers total recognition of the superiority of Vital over other kabbalists, as well as his own acceptance of the truth of Judaism over Christianity. However, Vital must have ultimately associated the phrase Keisar Romi (Roman Caesar) with the destruction of the Second Temple by Titus. The sudden interruption of the dream reflects an unconscious resistance, even while asleep, to the teaching of kabbalistic secrets to a gentile. Vital nevertheless started to reveal some parts of kabbalah before awakening.

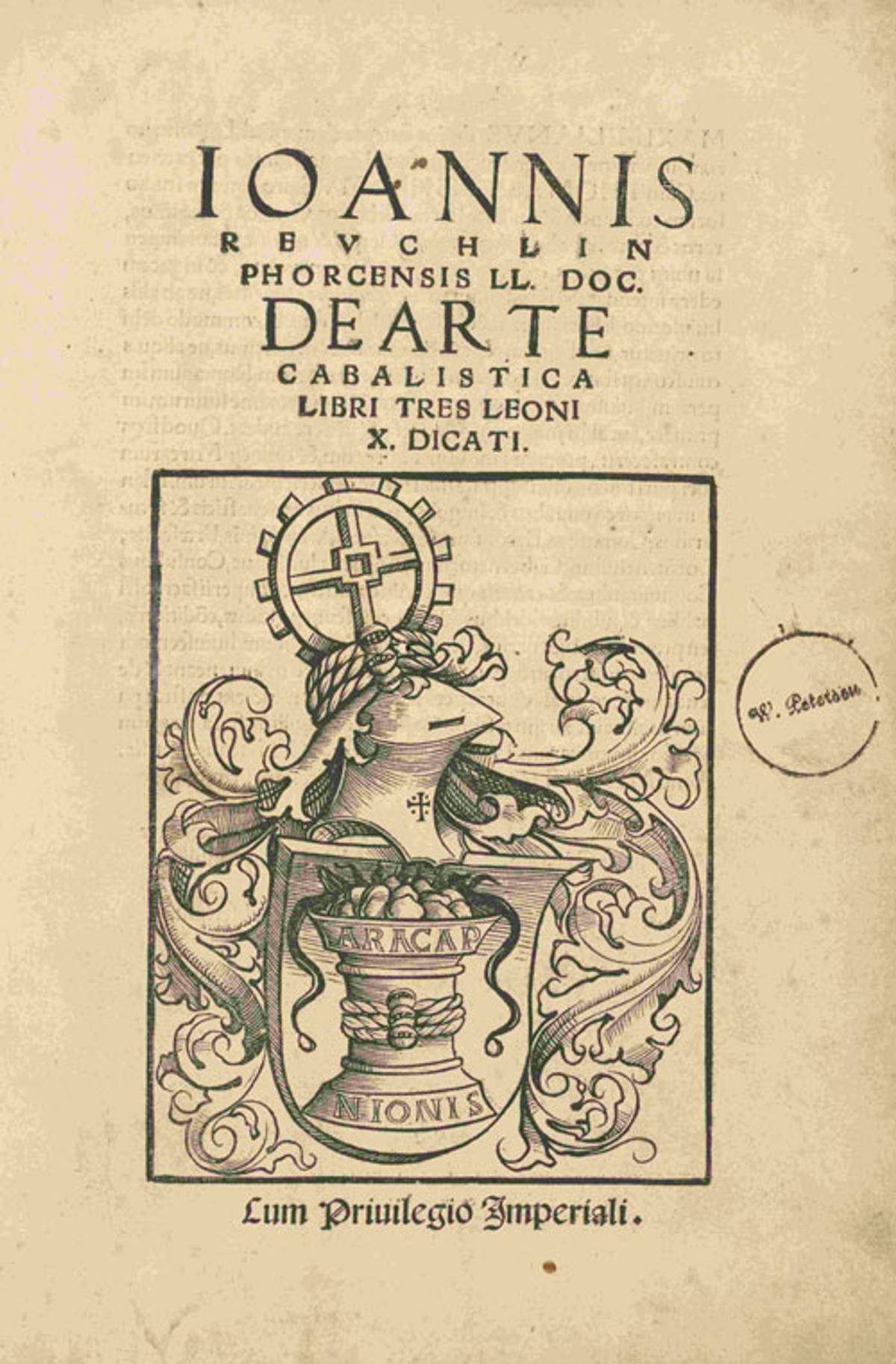

Thus, though only in a dream, intellectual exchange between the greatest of the kabbalists, the student of Luria who had forbidden the export of kabbalah from the Land of Israel, and the pope was imagined to have taken place. Indeed, there is historical background for this assumption. There are at least two examples of dedications of kabbalistic books to the pope prior to Vital’s dream: Reuchlin dedicated his De arte cabalistica to Pope Leo X; and around 1575, Lazarus da Viterbo dedicated a Latin kabbalistic treatise on the Jubilee to Gregory XIl. Vital, a kabbalist of Italian extraction and a member of a Calabrian family, had been born in the Land of Israel, yet was still called Hayyim Calabrese.

This dream is also interesting from another point of view: Safed is located in the Galilee, an area where Muslim and, to a certain extent, Druze cultures were dominant, not to mention the Ottoman administration. Some kabbalists active there in the 16th century came from Muslim countries, especially North Africa. Vital even studied occult sciences with Arab masters. R. Joseph Karo visited a tekie, a small Sufi monastery, as he himself confessed.

Yet while there is little reason to doubt that kabbalists were acquainted with Muslim thought and mystical practices, both the attraction and repulsion documented in the writings of Safedian kabbalists are formulated relative to cultural processes that were taking place in Italy. To recall a statement of Karo: “Someone is where his thought is.” Nevertheless, it will be too simplistic to relate all the main developments in Safedian kabbalah to Italy, even less to the awareness of the dangers inherent in Christian kabbalah. As mentioned above, there were various factors behind the arrival of the kabbalists in Safed and the interaction between them there, and all of them contributed to the creativity in the town. So, while emphasizing these topics, I do not rule out the possibility of a substantial impact of additional sources—Muslim, Druze, or other, such as Orthodox Christianity—or the importance of other spiritual trends that flourished in the kabbalistic center in Safed.

Awareness of the emergence of Christian kabbalah may account for a crucial turn in Isaac Luria’s politics of dissemination of his type of kabbalah. According to one of the most important documents describing the study of Luria’s secrets in his circle, he explicitly forbade the disclosure of those secrets to kabbalists outside his small circle and their dissemination outside the Land of Israel. Luria’s students and those of Vital, themselves mature kabbalists, had to sign pledges not to disclose Lurianic secrets. This is a clear-cut change that has not as yet been satisfactorily explained, given the quite exoteric propensity of his master Cordovero and his disciples. Is it connected with the danger of another “exile of the Torah”? I am not sure that the connection between the claim and a certain aspect of the ritual of tikkun hatzot regarding the secrets of the Torah, on the one hand, and the change in Luria’s politics of esotericism, on the other, can be demonstrated in a conclusive manner. Yet such a nexus seems plausible.

Finally, Lurianic kabbalah as formulated in the Galilee in its different versions is reticent toward philosophical thought. This anti-philosophical bent is certainly not new in the history of kabbalah, and not the strongest. We can easily trace it to earlier sources in Spanish kabbalah, and its reverberations outside the Iberian Peninsula after the expulsion. It is obvious that the powerful reliance on the Zohar, conceived of as an inspired book, was accompanied by the rejection of intellectual speculations in matters of kabbalah.

In the case of Luria, the centrality of the Zohar—a bit less evident in Cordovero—was accompanied by a certain purist approach, far less synthetic, harmonistic, or eclectic than Cordovero’s books. Luria’s works are more homogenous, unlike the more harmonizing and eclectic works of Cordovero, at least as regards his most influential book, Pardes Rimmonim. To a certain degree, we may describe what is imagined to be Luria’s thought as a case of counter-Renaissance, to echo Hiram Haydn’s term. Indeed, the more magically oriented system of Cordovero is more consonant with a Renaissance mode found in Pico and his many followers in what is termed the “occult philosophy.” Moreover, Cordovero’s cosmoeroticism is much closer to Renaissance theories. In a certain propensity to purism and counter-Renaissance, Luria, surprisingly, is in the same camp as the most adamant critic of kabbalah, Leon Modena.

On the other hand, Luria, like several of his contemporaries in Safed, lived in an ambience of adherence to an ostensibly ancient text, the Zohar, attempting to relive the life of the “ancient” kabbalists by returning to the place where they believed the Zohar had been composed. Indeed, Liebes has compared Luria to Marsilio Ficino, another figure who revived an ancient body of learning.

There is no doubt that Safedian authors, kabbalists and non-kabbalists, enjoyed a special status among Italian Jews, as they did in other Jewish communities. Not only did important figures visit Safed, such as R. Mordekhai Dato and R. Moses Basola. The numerous laments expressed by Italian rabbis over the death of R. Joseph Karo are clear testimony to the veneration in which he was held in Italy.

The economic assistance extended by Italian Jewry to the Safedian community is also well known; one of the main figures in this respect was the most important kabbalist in Italy at the end of the 16th and the early 17th century, R. Menagem Azariah of Fano. In his preface to Pellah Harimmon, his compendium of Cordovero’s Pardes Rimmonim, his reverence for Cordovero and Luria knows scarcely any limit. Thus, it is clear that almost all Italian kabbalists in the late 16th and early 17th century accepted Safed’s superiority. That recognition was not only a matter of reverence, a feeling welling up from the special geographic location of Safed in the Holy Land, or the propinquity to sacred tombs. That is doubtless a fact, yet there are additional important dimensions to the veneration of the Safedians. Their intellectual achievements were impressive. Karo and Cordovero wrote comprehensive systems, and Luria was imagined by his students, though in different ways, to have produced the most systematic exposition of kabbalah, the first in halakhah and the latter two on kabbalah, exemplary achievements that are milestones in the creativity of generations of Jewish writers before and since. It is this outstanding contribution to Jewish thought that spurred recognition by Italian thinkers and Jewish authors elsewhere.

If the objective attainments are the main source of reverence, there is another factor that must have played a role in the aura of sanctity surrounding the image of the Safedians: they were not only preeminent minds in matters of Judaism but belonged to powerful groups, and their cooperation must have enhanced their achievements as individuals. By contrast, the Italian counterparts of the Safedian kabbalists were not organized in a definite grouping. There is no extant written agreement about keeping secrets with respect to any group of Italian kabbalists. In general, Italian kabbalists showed no interest in maintaining secrecy. The names of R. Isaac de Lattes, R. Abraham ben Meshullam of San Angelo, R. Berakhiel Kaufmann, R. Mordekhai Dato, R. Abraham Yagel, and R. Moses Basola hardly constitute a group. With the exception of the family relationship between the first two, and their common sources, it is hard to document a significant common literary activity except the participation by some in the project of printing the Zohar.

Unlike Safedian kabbalah in both its major schools, which emerged in a small compact place and was organized in relatively coherent study groups, Italian kabbalah in the second half of the 16th century is marked by the presence of various individuals. Viewed from this vantage, they bore more similarity to the Spanish kabbalists immediately after the Spanish expulsion. Though they may have known one another, no one ever described them as a group. They thus represent a mode of creativity that differs dramatically from the emphasis on the importance of the group found in some kabbalistic circles in Spain: Nahmanides’ circle in Catalonia, the circle of the Zohar in Castile, and the Sefer Hameshiv circle apparently likewise in Castile, or their reverberations in Safed. In the Galilean town, there is solid evidence that a group, the havurah, sometimes called the havurah kedushah, the holy fraternity, not only afforded an opportunity to pursue rabbinic and kabbalistic studies in common, but was also a fraternity that undertook peregrinations around Safed for mystical purposes. Nor do the Italian Jewish kabbalists follow the pattern of the Accademia in Florence in the 15th century.

To an appreciable extent, kabbalistic literature of the Italian Renaissance among Jews and Christians relied on kabbalistic traditions articulated and widespread in Italy in the two centuries preceding the end of the 15th century, basically the writings of Abraham Abulafia and Menahem Recanati. They were studied without a kabbalistic master. The classic work of the Spanish kabbalah, the Zohar, had little impact before its first printing in the mid-16th century. This is part of a more philosophical orientation among Renaissance Italian Jews, who differed intellectually from the far more particularistic state of mind dominant in Spain and then Safed.

R. Abraham Yagel did not become a Lurianic kabbalist, notwithstanding the fact that he was aware of the existence of this sort of kabbalah. In contact with R. Menahem Azariah of Fano, the chief Italian kabbalist who introduced versions of Lurianism, Yagel apparently resisted the new wave of kabbalism. He writes, for example, that he heard that R. Hayyim Vital was a wondrous kabbalist, a student of Luria and head of the kabbalists in the Galilee. Does this statement imply that Vital was indeed an important kabbalist, but only insofar as the kabbalists of Safed are concerned? Such a reading would strongly support a claim made in this study that an awareness of the difference between the two centers is not only a matter of the phenomenology of a modern scholar, but part of the awareness of the 16th-century kabbalist, and that such an awareness influenced his evaluation and allegiance. Yagel’s reticence to adopt the system of Vital and Luria may indicate that this is the real significance behind the above formulation. In any case, it is obvious that his propensity for both kabbalah and philosophy, including that of the Renaissance, sparked a resistance toward the mythical tenor of Safedian traditions.

It is important to note the long Italian tradition that identified the sefirot with Platonic ideas. It perhaps began in the late 13th century with R. Nathan ben Sa’adiah Harar, becoming explicit in R. Judah Romano, R. Isaac Abravanel, R. Yebiel Nissim da Pisa, Mordekhai Rossilo, R. Abraham Yagel, R. Azariah de’ Rossi, and then in Leon Modena. Thus, the association of Platonic philosophy with kabbalah, evident in Herrera and in Delmedigo, represents just another more intense phase in the history of the affinities, real or imaginary, between the two types of speculation. Nonetheless, it is still an open question whether some concepts of sefirot might have been connected historically and directly (or indirectly) with Platonism. However, it is certain that beginning in the 16th century in Italy, the nexus between the two is mentioned.

After the disintegration of the center of kabbalah in Safed, Lurianic kabbalistic writings arrived in Italy as early as 1580, when R. Samson Bakki, a student of R. Joseph ibn Tabbul, sent an entire Lurianic treatise from Jerusalem to Italy, and R. Ezra of Fano copied Lurianic material, apparently in the Land of Israel, which he then brought to Italy. We are concerned here with one of the changes Lurianism underwent in Italy, especially in the manner it was formulated by R. Israel Sarug. Let me start the short survey of the affinities between the two types of lore with a citation from Joseph Delmedigo’s Novelot Hokhma. After quoting at length the descriptions of the first stages of Creation according to the malbush theory identified as that of R. Israel Sarug, Joseph Delmedigo writes: “As I announced beforehand, most of what I wrote here is taken almost verbatim from the books of the disciples of Luria. Therefore, let no philosopher criticize our words, but if his opinion is proper, he should interpret and divert them to the view of the true philosophers, and he will be blessed by God.”

The positive attitude toward a philosophical interpretation is conspicuous: the philosopher will be blessed for such an enterprise. What is fascinating is the manner in which this interpretation should be done: the words of Luria and his disciples should be diverted (the Hebrew is yatteh) so that they may become closer to, or perhaps even coincide with, the opinion of the true philosophers. This means that the latter may possess a sort of truth that kabbalistic writings, including Luria’s, may perhaps approximate but do not express in clear terms.

It is useful to examine the manner in which an Oriental kabbalist was portrayed by Leon Modena. He describes the activity of R. Israel Sarug: “And I have heard, too, from the mouth of the kabbalist R. Israel Sarug, an outstanding pupil of Luria, blessed be his memory ... that there is no difference between kabbalah and philosophy. And all that [Sarug] taught about kabbalah, he interpreted through philosophy.” I assume that this passage contains the words of two speakers: those of Sarug, to the effect that there is no difference between philosophy and kabbalah, and Modena’s own statement about Sarug’s interpretation of kabbalah.

Though Modena mentions Plato in connection with two other kabbalists—R. Jacob Nahamias (according to a testimony of R. Joseph Delmedigo) and his own student R. Joseph Hamis—the Greek philosopher is not mentioned in Sarug’s own statement or in Modena’s: both use the more general term “philosophy.” Nevertheless, Gershom Scholem interprets this term as “certainly” referring to “Platonic philosophy.” Alexander Altmann has already questioned this view and pointed out that there is insufficient evidence for such an interpretation. A perusal of Sarug’s works reveals no quotation of Plato or any Platonic thinker. We thus have to ask ourselves whether Modena’s statements about Sarug are reliable or perhaps only a weapon used by Modena in his attack on kabbalah. I think it almost inconceivable that Modena would falsify a statement of Sarug and then add his interpretation. Sarug presumably taught his version of Lurianic kabbalah without any philosophical quotations. This version was written by Sarug himself or his pupils; this is the meaning of the phrase “all he taught about kabbalah.” Afterward, and apparently only orally, a philosophical interpretation was given.

Yet how could Sarug offer a philosophical interpretation that had nothing to do with the original kabbalistic text, even more so in Italy, where some among the Jewish elite were engaged in exploring the philosophical culture of the Renaissance? A probable answer to this question may be that though Platonic philosophy cannot be detected in Sarug’s works, traces of another philosophy could be hidden in his works and taught orally by Sarug through his kabbalistic terms.

I analyzed Modena’s short statement to emphasize the selective will of Jewish Italian circles: though transmitting the sacrosanct Lurianic teachings, Sarug claimed that there was no difference between kabbalah and philosophy, whatever that philosophy may be. Perhaps we have a reverberation of the Renaissance attitude toward religious knowledge known as prisca theologia, which assumed a correspondence between various bodies of ancient knowledge. I would argue that the insistence on a correspondence between kabbalah and philosophy stands in strong opposition to the Safedian reticence toward philosophy, as mentioned above.

The above dynamics of rapid exchange between Safed and Italy is unparalleled insofar as Safed and another center are concerned, not only in Europe but throughout the entire Jewish world. Nothing similar is known regarding the arrival of Cordoverian kabbalah, or regarding the availability of Lurianic kabbalah in print and by oral teaching, paralleling the content of the aforementioned documents. In fact, as we learn from the very first lines of the introduction by R. Menabem Azariah of Fano to his Pelah Harimmon, he compiled at least the second version of his compendium of Cordovero’s Pardes Rimmonim at the request of R. Isaac ben Mordekhai of Poland (described as a distinguished scholar who came to study with him) and for the rabbis of Ashkenaz. This is evidence that Italy around 1600 became a center in itself, a hub from where kabbalah radiated to the North.

Adapted from “Italy in Safed, Safed in Italy: Toward an Interactive History of 16th-Century Kabbalah,” in David B. Ruderman and Giuseppe Veltri, eds., Cultural Intermediaries: Jewish Intellectuals in Early Modern Italy. Reprinted with permission of University of Pennsylvania Press. All rights reserved.

Moshe Idel is professor emeritus in Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, and a Senior Researcher at the Shalom Hartman Institute.