The God That Failed

The collection of essays by disillusioned former communists has been largely forgotten after decades of global popularity. In our age of ideological extremism, it’s well worth revisiting.

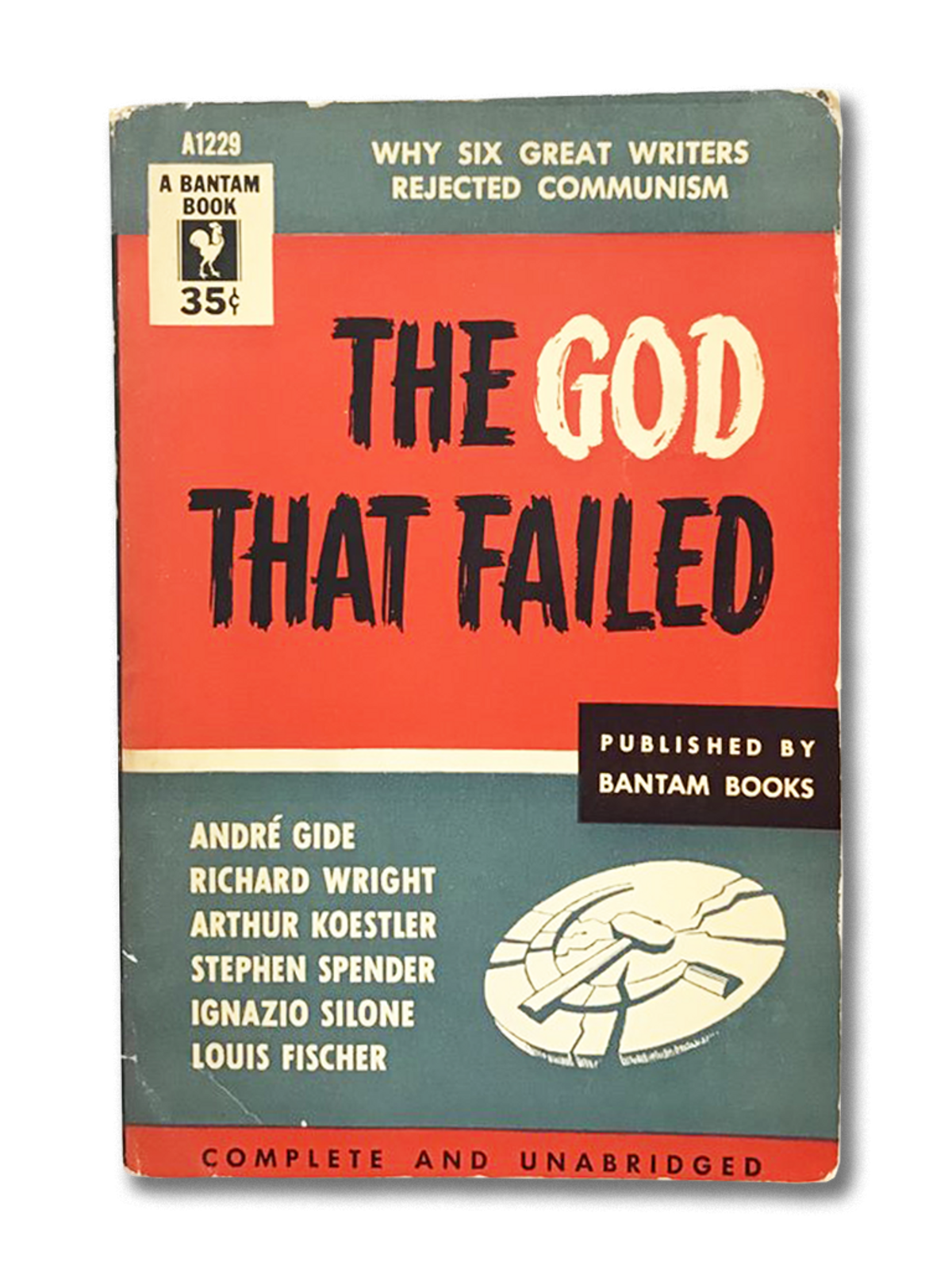

The God That Failed, a collection of essays by six former communists published 70 years ago, sold hundreds of thousands of copies in its first decade in print. Those figures refer to British and American sales only—if we include the sales of the many foreign translations published in the ’50s and ’60s (including a translation into Hebrew) and add the figures for the subsequent decades, the book was distributed in the millions. The book elicited an extraordinarily powerful response from its many readers—damned by loyal communists and sympathizers and lauded by conservatives and former communists who had become disillusioned with Soviet policies.

Book sales were only one way that The God That Failed was distributed. Copies were also supplied by the Congress for Cultural Freedom, a CIA-funded organization created by the U.S. government to counter Soviet influence among European intellectuals. Distribution of the book was among the first of its many activities, which included radio broadcasts, conferences, documentary films, and book publishing. As Michael Scammell pointed out in an essay on the 1956 publication of Doctor Zhivago (in which the CIA also played a part), “The CIA had a large number of officials who had strong literary credentials and loved books … They believed in the power of ideas.”

The anthology’s editor, British Member of Parliament Richard Crossman, wrote that “In this book, six intellectuals describe the journey into Communism, and the return. Our concern was to study the state of mind of the Communist convert, and the atmosphere of the period—from 1917 to 1939—when conversion was so common.”

Of note is Crossman’s use of the words “conversion” and “convert,” terms borrowed from the realm of religion, as is the book’s title, The God That Failed. This comparison between conversion to communism and religious experience spoke powerfully to Arthur Koestler, who conceived of the book along with Crossman. The religious flavor of the book was emphasized in the original British edition, which carried the subtitle “a confession.” Why this word was missing from the American printings I have not been able to ascertain.

Reviewers of the time noted this religious terminology. In a review of The God That Failed in Commentary, literary critic Granville Hicks wrote that “What Communism can offer the intellectuals can be described, as the title of this volume indicates, in religious terms. It has offered them redemption from sin, the fellowship of true believers, and all-inclusive theology.” In Hicks’ terms, “redemption from sin” means relief from a sense of guilt that stems from “the intellectual’s awareness of the contrast between his own well-being and the woes of society.”

In compiling the book, Crossman, in consultation with Koestler—who penned the first of the book’s essays—elicited contributions from six former communists, four Europeans, and two Americans. Crossman divides the six writers into two groups, “Initiates,” and “Worshipers From Afar.” The “Initiates”—Arthur Koestler, Ignazio Silone, and Richard Wright—had been Communist Party members, activists, and organizers.

The “Worshipers From Afar” (a category that would later be dubbed “fellow travelers”), were André Gide, Louis Fischer, and Stephen Spender. These writers were sympathetic to the aims of the Communist Party but never actually joined it. Never having been in the party, they did not have to undergo the wrenching experience of leaving it. But each of these writers was scarred by their disillusionment with a cause they once passionately supported.

In our identity-conscious age readers of the book can’t help but notice that three of the essayists—Arthur Koestler, Louis Fischer, and Stephen Spender—were born into Jewish families, that Richard Wright was African American, and that Ignazio Silone and André Gide were born into Catholic families and left the church in their youth. Gide was also homosexual. But in 1951, when The God That Failed was published and reviewed, these markers of identity were not mentioned or alluded to. For the engaged intellectuals of the time, political affiliation was the essential marker of identity, not one’s religion or sexual orientation.

In the opening essay, Arthur Koestler wrote: “I became converted because I was ripe for it and lived in a disintegrating society thirsting for faith.” Here Koestler speaks of his coming to communism in religious terms. Koestler wrote that after having read Marx, Engels, and Lenin, “something had clicked in my brain that shook me like a mental explosion. To say that one had ‘seen the light’ is a poor description of the mental rapture which only the convert knows, regardless of what faith he has been converted to.”

Another image for the appeal of communism is drug addiction. “The addiction to the Soviet myth,” Koestler wrote, “is as tenacious and difficult to cure as any other addiction. After the Lost Weekend in Utopia the temptation is strong to have just one last drop, even if watered down and sold under a different label.” For Koestler those different labels were the many forms of popular front politics of the late 1930s.

Koestler’s essay closes with a biblical allusion:

“I served the Communist Party for seven years—the same length of time as Jacob tended Laban’s sheep to win Rachel his daughter. When the time was up, the bride was led into his dark tent; only the next morning did he discover that his ardors had been spent not on the lovely Rachel but on the ugly Leah. I wonder whether he ever recovered from the shock of having slept with an illusion. I wonder whether afterwards he believed that he had ever believed in it. I wonder whether the happy end of the legend will be repeated; for at the price of another seven years of labor, Jacob was given Rachel too, and the illusion became flesh. And the seven years seemed unto him but a few days, for the love he had for her.”

In The New York Times Book Review on Jan. 8, 1950, Rebecca West, the eminent British woman of letters, penned a laudatory review of The God That Failed. It opened with this trenchant observation: “There is no subject on which it is more difficult to establish communication with one’s fellow-creatures than anti-communism.” West described Arthur Koestler’s essay as “one of the most handsome presents that has ever been given to the future historians of our time.” She concludes her review with this observation: “The value of this book is not that its authors showed themselves outstanding, but they were typical.”

The God That Failed was translated into Hebrew in 1953, soon after its U.S. publication. The translation, by Efraim Kerlis, was published by Pales Press of Tel Aviv. Their book list included the translation of another anti-Stalinist classic, Orwell’s 1984. By then, Arthur Koestler was well-known to Israeli readers. His 1947 novel Thieves in the Night was immensely popular there. Having read that novel and translations of Koestler’s newspaper articles, Israeli readers knew that Koestler had in his youth been an ardent Zionist, served as Vladimir Jabotinsky’s personal secretary, and was for a short period a member of Kibbutz Heftzibah. And they knew too that in Koestler’s case an embrace of communism did not entail a rejection of Zionism.

In the first half of the 1950s, Israeli admiration for the USSR was a widespread political and cultural phenomenon. Concerning the cultural life of Israel’s first decade, literary historian Dan Laor has remarked on the enchantment with the USSR shared by many on the Israeli socialist left. “This group included public servants, writers, intellectuals, journalists, veterans of the Haganah and the Palmach, Kibbutz members, and youth group leaders. They viewed the USSR as a model of a progressive society, a view strengthened by the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany.” Mapam (first Hashomer Hatzair), the leftist party that represented these views, was so bound to the Soviet myth that in May of 1953 they publicly mourned the death of Josef Stalin. The Mapam newspaper Al Hamishmar printed a bereavement notice on its front page which announced that “Mapam is shocked to hear of the great tragedy that has befallen the peoples of the USSR, the world proletariat, and all of progressive humanity on the death of the great leader and general, Josef Stalin.” These admirers were fierce critics of The God That Failed.

Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s party, Mapai, shared none of Mapam’s admiration for the Soviet system and they ridiculed the bereavement notice for Stalin. Since the late 1930s Ben-Gurion, long an admirer of Lenin, had been convinced of Stalin’s hostility to Jews and Israel. He called Soviet socialism a deception. “It was as far from real socialism as East is from West,” he wrote.

Mapam nostalgia for Stalin persisted long after the dictator’s death. In the late 1960s, I was living on a Hashomer Hatzair kibbutz that had once been particularly enamored with the Soviet experiment. The kibbutz’s communal dining room was decorated with posters of agricultural produce and smiling children. But one large wall—with a faded spot in the center—was left empty. When I asked one of the kibbutz vatikim (old timers) why it was left empty and unsightly, she said: “That’s where the picture of Stalin used to hang. After Nikita Khrushchev’s condemnation of Stalin we took it off the wall. But every time the question of what to put up in its place came up at our community meetings a fight broke out. So we left it as it is.” Decades ago that particular bastion of Israeli socialism—along with many other kibbutzim—was privatized and turned into a shopping center and hotel. When I looked it up on Google recently, I found that it was now so financially successful that it merited a Dun & Bradstreet rating.

Among the one-time Soviet admirers anthologized in The God That Failed, Koestler, Fischer, and Spender were all from Jewish families. But in each of their essays there is no mention of Jews or Zionism. Richard Crossman, the book’s editor, was also a Zionist; this too is overlooked in The God That Failed. This omission is notable, as Koestler spent years in Palestine intensely involved with Zionism, Fischer served in the Jewish Legion in World War I, and Spender was known to be deeply connected to his Jewish ancestry through his grandparents.

Stephen Spender wrote in his 1951 autobiography, World Within World, of his adolescence in England. “That we were of Jewish as well as German origin was passed over in silence, or with slight embarrassment, by my family, either because, as with my grandfather and his brothers it was taken for granted, or because, with his descendants, it was deliberately ignored … When, at the age of sixteen. I became aware of our Jewish blood; I began to feel Jewish. At school, where there were many Hampstead Jews, I began to realize that I had more in common with the sensitive, rather soft, inquisitive, interior Jewish boys, than with the aloof, hard, external English.” Like Koestler, Spender speaks of his attraction to communism in terms borrowed from religious discourse: “It is obvious that there were elements of mysticism in this faith. Indeed, I think that this is an attraction of communism for the intellectual. To believe in political action and economic forces which will release new energies in the world is a release of energy in oneself.”

Like Koestler and Spender, Louis Fischer, born in Philadelphia to parents who fled from Ukraine to the U.S. in the 1890s, avoids mentioning his Jewish family in the book. The closest we get to an allusion to Jewish origins is in the opening paragraph. “My parents, born in the small town of Shpola, near Kiev, told me of bloody pogroms perpetrated by vodka-filled muzhiks.” This observation comes in service of explaining Fischer’s childhood fascination with Russia, which led him to travel there as a freelance journalist in 1922. In dispatches to New York newspapers, Fischer wrote of the Russian people’s “infectious enthusiasm” for the revolution. He explained his personal stake in the socialist cause in this manner. “Born and bred in poverty, I instinctively welcomed any endeavor to eradicate it.”

Over the next 17 years, Fischer reported from Russia, for the most part portraying the regime positively. He finally left the party after the Soviet-Nazi pact of August 1939. He termed that moment his “Kronstadt,” his moment of disillusionment with communism. The actual Kronstadt had been in 1921, when the Red Army crushed a rebellion by Soviet sailors and civilians opposed to the harsh measures taken by the Bolshevik regime. Thousands of the rebels were killed by the army in the suppression of this revolt. Many international supporters of the Bolsheviks were deeply disillusioned by this slaughter. Among them were anarchists Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. Referring to the different times when communists decided to leave the party, Fischer said that “What counts decisively is the Kronstadt. Until its advent, one may waver emotionally or doubt intellectually or even reject the cause altogether in one’s mind and yet refuse to attack it.”

Fischer, Spender, and Koestler also avoided any mention of Jewish participation in the communist movement. It was as if mention of Jews and communism was too raw and volatile a topic at that historical moment. The only mention of Jews in The God That Failed is in Richard Wright’s essay on his attraction to communist activism in Chicago and his eventual break with the local and national party. At least four times in his essay Wright mentions the Chicago Jewish Communist Party members who brought him into their circle.

Crossman and Koestler, passionately anti-communist as they were, were also reluctant to be branded as such, and have The God That Failed identified with the anti-communist hysteria emerging then in the United States. In his essay, Louis Fischer described these fanatical anti-communists as “authoritarians by inner compulsion.” He wrote that “Among the ex-Communists and among those Soviet supporters who, like myself, were never Communists, there is a type that might be called authoritarian by inner compulsion. When he finds a new totalitarianism, he fights Communism with Communist-like violence and intolerance.”

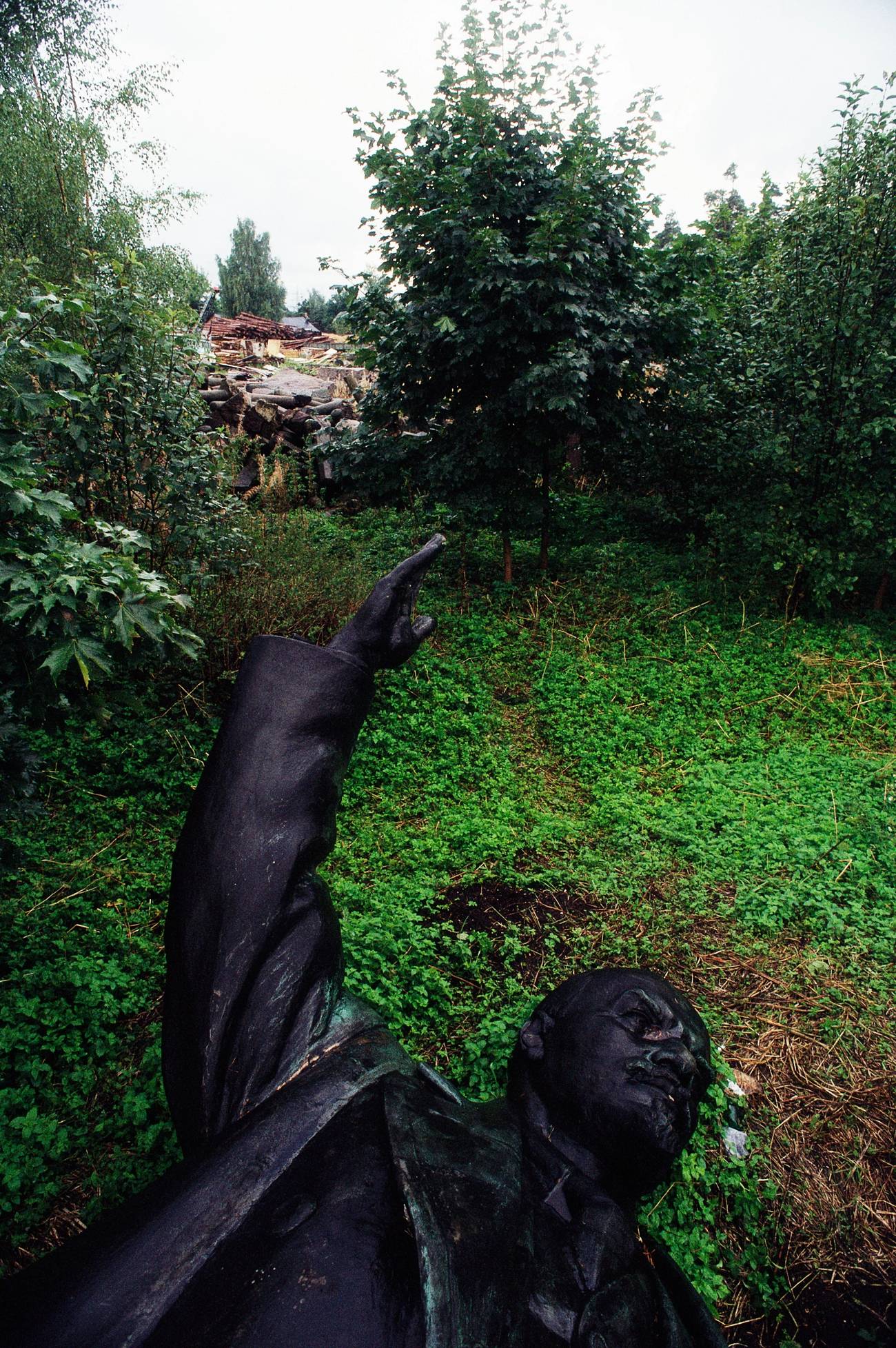

The God That Failed was a weapon in the “cultural Cold War” that accompanied the more tangible aspects of the conflict. By 1991, with the fall of the Soviet Union, the book seemed no longer relevant. As a weapon in the Cold War, it was last published in the U.S. in the mid-1980s by the conservative Henry Regnery Publishing house. After the fall of the USSR, it seems that the book held little appeal and was of interest only to historians of the ideological struggles of the 20th century. A 2001 publication of The God That Failed by Columbia University Press was in that spirit. That edition’s editor noted that for college students at the beginning of the 21st century, “the passions and fears of the Cold War lie in the distant past.” But today, 20 years later, the book feels to me increasingly relevant, as more and more young people, both in the U.S. and in Israel, are pulled in by ideological extremes.

Shalom Goldman is Professor of Religion at Middlebury College. His most recent book is Starstruck in the Promised Land: How the Arts Shaped American Passions about Israel.