The Rabbinic Network

Using new digital techniques to unravel foundational questions about the Talmud

The great sage Hillel the Elder, the Babylonian Talmud tells us, was dirt poor, and even then he spent half of his meager earnings to attend the rabbinic study house. One day, when he did not make his usual pittance, he went to the roof of the study house so he could still listen to the day’s lesson through the skylight. It began to snow, but that did not deter him. The sages inside noted the figure above them and went to the roof. They dug him out of 4 1/2 feet of snow, brought him into the study house to warm him up and revive him, and from that moment on, they accepted him as a serious student of Torah (Yoma 35b).

I like to teach this story. The Talmud explicitly cites it in order to show that even a poor person should study Torah. Anyone, no matter their humble beginnings, has the potential to be a great sage. But it also raises a serious historical question: Is it true? Given that there is at least some hyperbole in the story (that’s a lot of snow!), what, if anything, can we learn from it about the actual historical figure Hillel? And by extension, can we trust anything that the Talmud tells us?

In the last two decades of the 20th century, the small community of academic scholars of rabbinic literature went to war with itself over this question. For the previous 150 years or so, since the dawn of the academic study of rabbinic literature, scholars tended to take the Talmud’s historical claims more or less at face value. If the Talmud tells us that the Babylonian sage Rava said something, or that Hillel had humble origins, why shouldn’t we believe it? Represented most vocally by Jonah Fraenkel and Jacob Neusner (who, ironically, began his own career mining the Babylonian Talmud for historical information about the Jewish community of Babylonia), scholars began to challenge this assumption. They claimed that, far from accurately conveying traditions, the later editors of rabbinic literature (e.g., the redactors of the Talmud or the stammaim) so actively reworked them that they obliterated any recoverable traces of history, even if there were any to begin with. With no reliable evidence, the entire possibility of knowing anything about a sage from the stories told about him collapses.

At the same time, scholars increasingly looked at attributions with skepticism. The Talmud is full of rabbinic citations, noting which rabbis said what. These citations are often recorded in chains: Rabbi X said that Rabbi Y said that Rabbi Z said something. On one hand, the Talmud seems very concerned with the principle of accurate transmission of statements in the name of their masters. On the other hand, the Talmud itself often admits its confusion about which rabbi actually said something, and variations in the many later manuscripts compound our certainty about these attributions. Now, on top of these well-known problems, some scholars suggest that active intervention by the stammaim swept away any hope of recovering accurate attributions.

As a graduate student during the heat of this rarefied internecine battle, I can say that it was not pretty. Positions hardened and scholars were forced to take sides. Academic articles and book reviews dripped with hostility, often taking on a personal tone. Conference presentations were places of war. When it came to academic hiring or determining whether to grant tenure, one’s position on this issue mattered a great deal.

And then, slowly, like many similar academic debates, it ended. This was partly due to intellectual exhaustion. There was simply no more to say, no new evidence, and no arguments to adduce. Maybe the move away from the debate also had something to do with the emergence of a new generation of scholars, who wanted to pursue a different set of questions in a less hostile environment.

Stepping back, it is helpful to consider what was, and what remains, at stake in this intellectual issue. How, and for whom, does it matter whether rabbinic attributions in the Talmud were accurate?

For anyone who seeks knowledge of individual sages—whether in order to produce edifying accounts of figures worthy of emulation or for historical reasons—the question of the relatability of attributions and the content of stories is, of course, critical. Unlike contemporary Greek, Roman, and Christian literature, rabbinic literature lacks individual authorship. We have tracts by the fourth-century rhetorician Libanius and the fifth-century Church Father Augustine, among hundreds if not thousands of other writings ascribed to individual authors, but not a single tract individually authored by a rabbi. Midrash, Mishnah, and Talmud all subsume individuals to the collective enterprise. Without being able to mine rabbinic sources for reliable biographical information, there was virtually no biographical information to be found.

A second issue at stake cuts to the heart of the traditional study of the Talmud. Among Jewish circles that study the Talmud as a religious document, and especially as a source of binding law (Halacha), individual attributions matter. That follows, in part, the Talmud itself, which seeks to ensure consistency between different statements made on different topics by the same rabbi. Both the medieval commentators (the Tosfot among them) and the modern student of Talmud continue to exert significant intellectual effort towards this task. In the Middle Ages, a hierarchy also developed for determining who, in the case of two rabbis disagreeing about a particular Halacha, should win. Declaring that all of the attributions lacked historical veracity throws into question both of these intellectual activities, thus threatening to upend the traditional study of rabbinic literature.

Finally, the stakes of attribution are high for academic historians. Without trusting attributions to rabbis, it is impossible to deconstruct the layers of a rabbinic text and thus to say anything about historical development. We can, in essence, never know anything about a rabbi, but also about the rabbis. Denying any reliability to attributions shuts down any attempt to recover the intellectual histories that were undoubtedly important in the formation of the final texts. We can never know how the rabbis emerged from their misty origins in the first century CE, in both Roman Judaea and Sassanian Babylonia, to become intellectual Jewish leaders some 500 years later. Without being able to date any of the traditions in rabbinic literature, we can scarcely know anything about the history of the Jews during this half-millennium. We can only talk of the literary representations and fantasies of the final redactors of these documents. It is no wonder that those who made their living as historians of the rabbinic period found this development so threatening.

The academic fights about attribution have had little impact beyond the academy. Authors continue to write about ancient rabbis as if we can know something about them. The world of the yeshiva continues with little awareness or interest in this discussion. The academic community, although bruised and unable to resolve the issue, has been chastened. Few scholars today take the stories about and sayings of the rabbis at face value, but so too, few sweepingly disregard the possibility of recovering material in rabbinic literature that can speak to historical periods prior to the time of the redaction. When scholars began to step away from this issue, they also began to step away from history. Wary of wading back into an acrimonious dispute, most scholars of rabbinic literature over the past two decades seem, to me, to focus more on literature and ideas, framing their questions in ways that have allowed them (legitimately) not to take a stand on the historicity of rabbinic traditions, or engage much with history at all. History, which drove the early years of the academic study of rabbinic literature, has taken a back seat.

The historical questions, though, remained. While scholars have increasingly come to the conclusion that the ancient rabbis worked in small disciple circles (as opposed, for example, to institutions such as the yeshiva, which only emerge much later), we still have only a vague idea of how those circles interacted and coalesced into something that might be called a “movement,” “class,” or “network.” How was it like, and not like, other historical networks, such as the Roman aristocracy or the Republic of Letters? How robust was it—could knocking out a few key figures lead to the collapse of the entire network? How did information move across it?

Until recently, the evaluation of these historical networks was largely a qualitative operation. Thinking of groups of historical actors as a network has allowed us to pose a number of new questions to our data. In 1997, Catherine Hezser, in her book The Social Structure of the Rabbinic Movement did exactly this for the classical rabbis, to great effect. Over the past 10 years, though, there has been a general explosion of interest in quantitative approaches to networks, led primarily in areas such as physics, biology, and computer science (e.g., the “page rank” of internet search engines is a determination of the importance of a particular page among a large network of relevant pages). Combined with the increased availability and accessibility of both digital tools for analysis and datasets to analyze, historians have also recently started exploring the utility of this kind of analysis on their own networks. Historians have experimented with both visualizing these networks (for two excellent examples, see Mapping the Republic of Letters and the Six Degrees of Francis Bacon) and using quantitative tools to better understand how they functioned.

A few years ago, as part of my increasing interest in such digital approaches (which often goes under the umbrella term, “digital humanities” or DH), I began to conceive of a project that would visualize and analyze the network of ancient rabbis. Such a project, I knew, faced formidable methodological obstacles. The same problems that stymied our reliance on historical attributions applied to our work: How could such a project be conceived when the manuscripts were messy and the attributions potentially unreliable?

I decided to begin by mapping a single interaction as presented in a single version of a single text: the rabbinic citation network presented in the Vilna edition of the Babylonian Talmud. Focusing the project in this manner has two advantages. First, among the different kinds of rabbinic interactions found in rabbinic literature (e.g., rabbis who ask questions of other rabbis; rabbis who visit other rabbis), citations—or rabbis who say things in the names of other rabbis—are by far the most numerous, making a good test case. Second, a full digital version of the Vilna edition of the Babylonian Talmud was freely available.

What was most important to me, though, was that the focus of the project was on the network as a whole rather than individual rabbis. My questions focused on how the network looked and functioned, not on the roles played by specific, historical rabbis (there are, in fact, networking projects running that focus on the latter—see especially the ones by Joshua Waxman and Maayan Zhitomirsky-Geffet and Gila Prebor). That is, my network makes no prior judgments (e.g., whether early or late, or from Palestine or Babylonia) about particular sages. The goal at this stage was simply to prepare and run the network analyses and to see what emerges. There are no inherent claims about whether the connections between rabbis in this network actually existed in real life, were the result of scribal mistakes, or were entirely fictional, created by a late editor. Those questions could wait until later.

The same problems that stymied our reliance on historical attributions applied to our work: How could such a project be conceived when the manuscripts were messy and the attributions potentially unreliable?

At this point, I joined forces with Michael Sperling, a retired data scientist who had turned his attention to graduate studies in Talmud (and who has a great deal more technical savvy than I). At least in general, the workflow was relatively clear. We used only the original Hebrew and Aramaic texts. We first assembled a list of the names of all the rabbis in the Babylonian Talmud, accounting for the fact that some rabbis are referred to by more than one name (and that sometimes the names used are inherently ambiguous, and could refer to more than one individual). Then, using that list, we found each place in the Talmud that listed two of these names in proximity to each other, and then pulled out the terms used to denote their interaction. Manually sorting through these terms, we determined the different patterns and formulas used to denote citations and then created a program that would isolate each of these citations. At the end of this process, we emerged with two lists: (1) rabbis, each with a unique numerical identifier and crosslinks to alternative ways of referring to that rabbi, and (2) citations, in the form of which rabbi cites whom (with both represented by their unique numerical identifiers).

Arriving at these two lists was by no means a fast, efficient, or easy process. It was an iterative process that literally took years. Each round of revisions required adjustments to the data and program. As with all DH projects, though, we had to make a judgment about when the data were good enough—if not quite perfect—to move to the next step. As is common in DH (as with scientific) projects, we have made both our programs and our data available to all so that, in addition to making our work transparent, others might refine and build upon it.

Now with our two lists of rabbis (in network parlance, “nodes”) and citations (“edges”) the next technical step was trivial. We imported those lists into a free and open-source network analysis program, Gephi, which then instantly created our visualizations and statistics. The more difficult task was, and remains, trying to interpret these results.

First, some numbers.

We found 5,039 individually named rabbis in all of classical rabbinic literature (there are another 823 alternative names for these same individuals). Of these rabbis, 1,956 appear at least once in the Babylonian Talmud. They were involved in a total of 5,245 citations, many of which were repetitions or involved the same pair of rabbis. When these were accounted for, we had left 1,210 unique combinations of one rabbi citing another, with a total of 630 rabbis appearing in at least one citation.

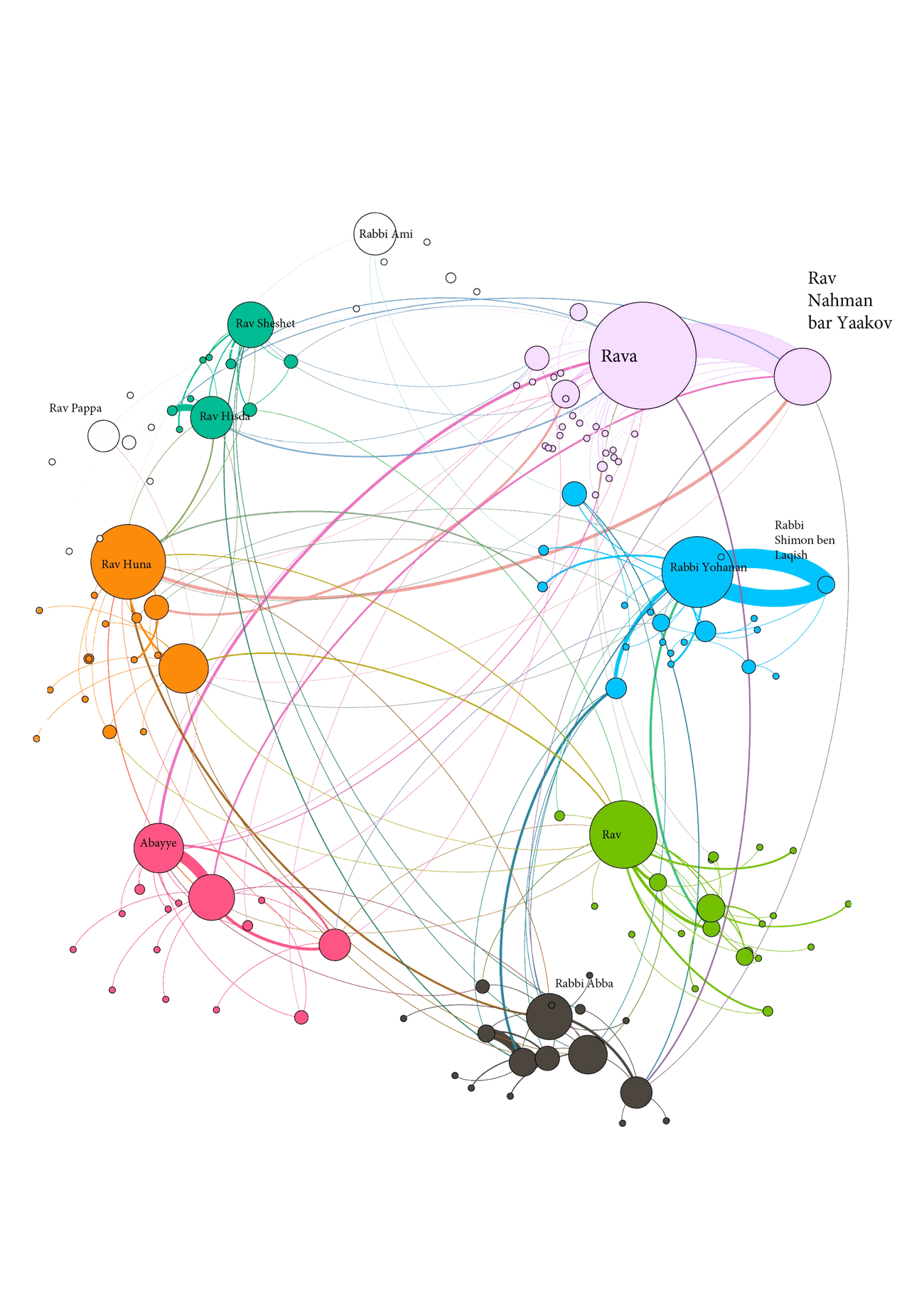

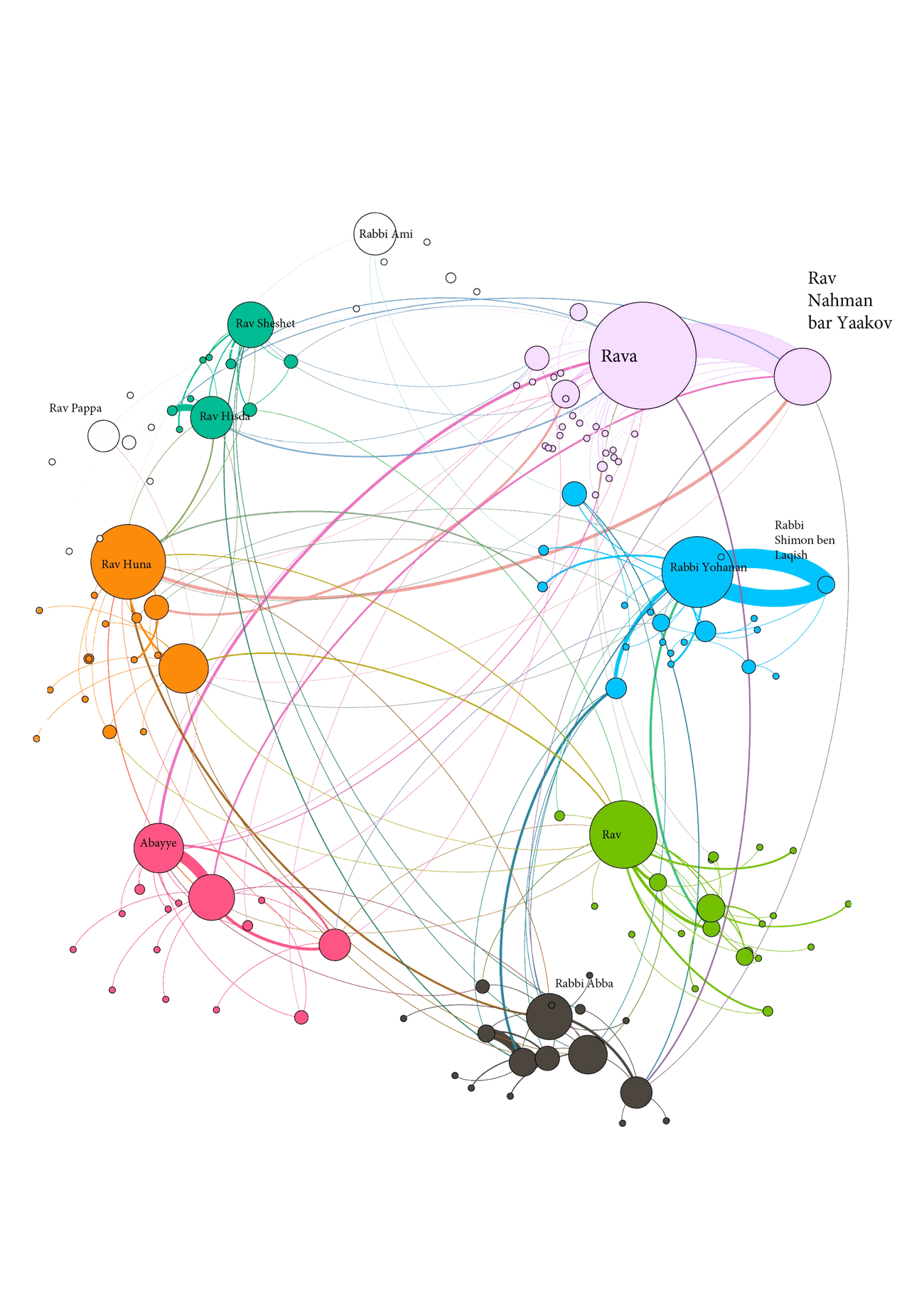

Visualization of this data allows us to better and more immediately grasp the meaning of these numbers. In figure 1, every dot represents a rabbi who appears in the Babylonian Talmud; the more unique interactions a rabbi has, the closer to the center he is. As can be seen from the isolated dots, most rabbis are not part of any citation link. Figure 2 includes only those 630 rabbis who appear in at least one citation chain. What is striking, and significant, about this visualization is that it shows its density. The rabbis who appear in citation chains are almost all connected to each other through these chains; there are very few isolated dyads or triads (which the Gephi algorithm plots along the margins).

We can dive further into the tangle in the middle of figure 2. We took all of the rabbis who appear in figure 2 and ran a sorting algorithm (the Louvain method) to determine if there were subcommunities, or clusters of rabbis that are more tightly connected to each other. The result is figure 3. We found six such subcommunities, each of which we assigned a different color. Each individual node is sized according to its “degree score,” that is, the number of rabbis connected to that rabbi in citation chains; the larger the circle, the more connections that rabbi has. Several of these subcommunities contain only one or a few large nodes, which we might expect from a “school” of successive disciple circles. Others are a bit more diffuse, but when sorted again with the same algorithm clearer, clusters often emerge. One of the more interesting results of these sortings for us was that they tended to cluster together rabbis in ways that are plausible. Although the algorithm knew nothing about whether a particular rabbi was Palestinian or Babylonian, for example, it tended to cluster Palestinians and Babylonians separately.

One of the goals of this project has been to understand the network as a whole, without focusing on individual rabbis. At a later stage, though, it will be important to focus back on these rabbis, combining this quantitative approach with a qualitative one. Network mapping can highlight rabbis who play unusual roles, whether as dominant figures who are cited far more frequently than others (e.g, Rav) or who seem to play a critical role in moving between Palestinian and Babylonian disciple circles (e.g., Rabbah bar bar Hana). Only a deeper, more traditional approach, though, can tell help us interpret such data.

Our next step will be to develop the networks of rabbis in the same edition of the Babylonian Talmud involved in other kinds of interactions (e.g., questions, visits) and to compare them to the citation network to check its compatibility. We then want to run the same analyses on other rabbinic texts and on different manuscripts. Our work is only beginning.

Dedicated to the memory of Yaakov Elman. I greatly miss not having had the opportunity to discuss these issues with him.

A full account of this research will be published in a forthcoming issue of AJS Review. The database itself can be explored here. The authors welcome all comments there.

Michael Satlow is a professor of religious studies and Judaic studies at Brown University. His most recent book is How the Bible Became Holy.