Who Were the Hasmoneans?

A Jewish populist movement that rejected Greece in favor of Iran, only to be conquered by Rome

The Hasmonean Jewish Kingdom came to an end in 63 BCE because of a rivalry between the brothers Aristobulus II and Hyrcanus II, both of whom appealed to the Roman Republic to intervene and settle the power struggle in their favor. In response to their call, the Roman General Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) was dispatched to the area. Twelve-thousand Jews were massacred in the Roman siege of Jerusalem, and the priests of the Temple were struck down at the altar. Rome annexed Judea, a move that over the next century or so would transform an out-of-the-way province into Roman Algeria or Vietnam and help give rise to both Christianity and rabbinic Judaism.

The Hasmoneans were a rural priestly family whose members later arose to occupy the office of the High Priest and later styled themselves as kings. In both cases, they acted as usurpers prompting, unwillingly, aversion from the Temple worship and longing for a king of the dynasty of the House of David.

After the death of Alexander the Great, who had conquered the Persian Achaemenian Empire, thus establishing the second global empire, his Macedonian generals divided his territories and began fighting each other. Judea fell to Ptolemy I who ruled Egypt since 305 BCE and had the Alexandrian Library built; it was during the rule of Ptolemy I or his son Ptolemy II the Great that the Pentateuch was translated into Greek. Ruling as Egypt’s pharaohs, the Ptolemean dynasty tended to be tolerant.

In 312 BCE, Seleucus, the Macedonian cavalry general of Alexander the Great, was made King at Babylon. Appian wrote that Seleucus ruled over “Mesopotamia, Armenia, ‘Seleucid’ Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapouria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania … as far as the river Indus ... The whole region from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus.” He founded two new capitals at Antioch on the Orontes (Antiochia, now in Turkey) and Seleucia on the Tigris, north of Babylon. Ruling such vast territories, the Seleucids opted for unitarism and, as a result, Hellenization; but such a huge state began to disintegrate quickly.

In the long series of Syrian wars (273-168 BCE) that followed, Judea and Samaria were brought under the Seleucid sway around 200 BCE when King Antiochus III the Great defeated the armies of Ptolemy V Epiphanes of Egypt at the Battle of Panium (Banias in Israel) during the Fifth Syrian War. The elites of Judea promoted extremist degrees of Hellenization and tried to drag the Seleucid government to support such efforts; a tradition was thus fixed in Jewish history, which gave birth in turn to the Soviet Yevsektsiya.

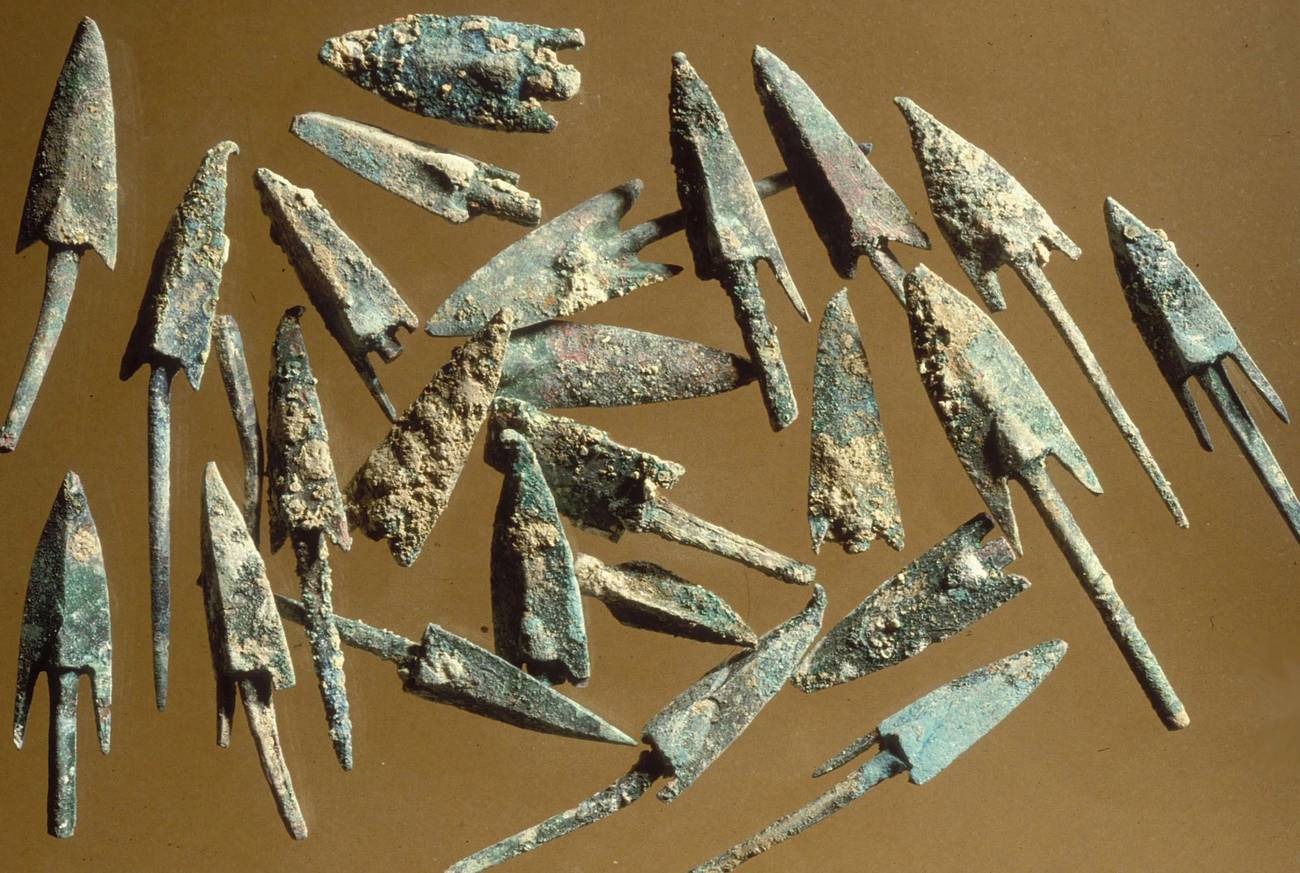

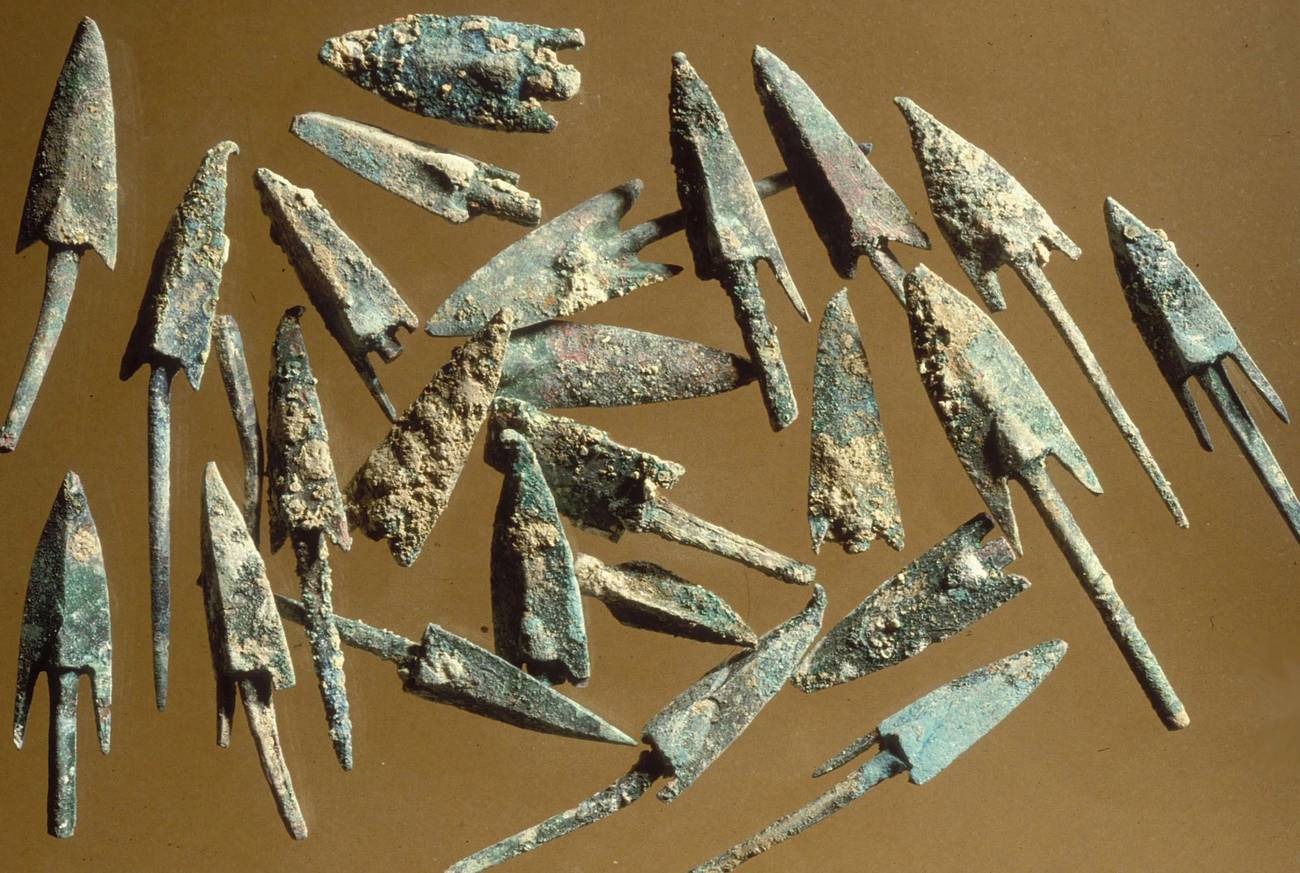

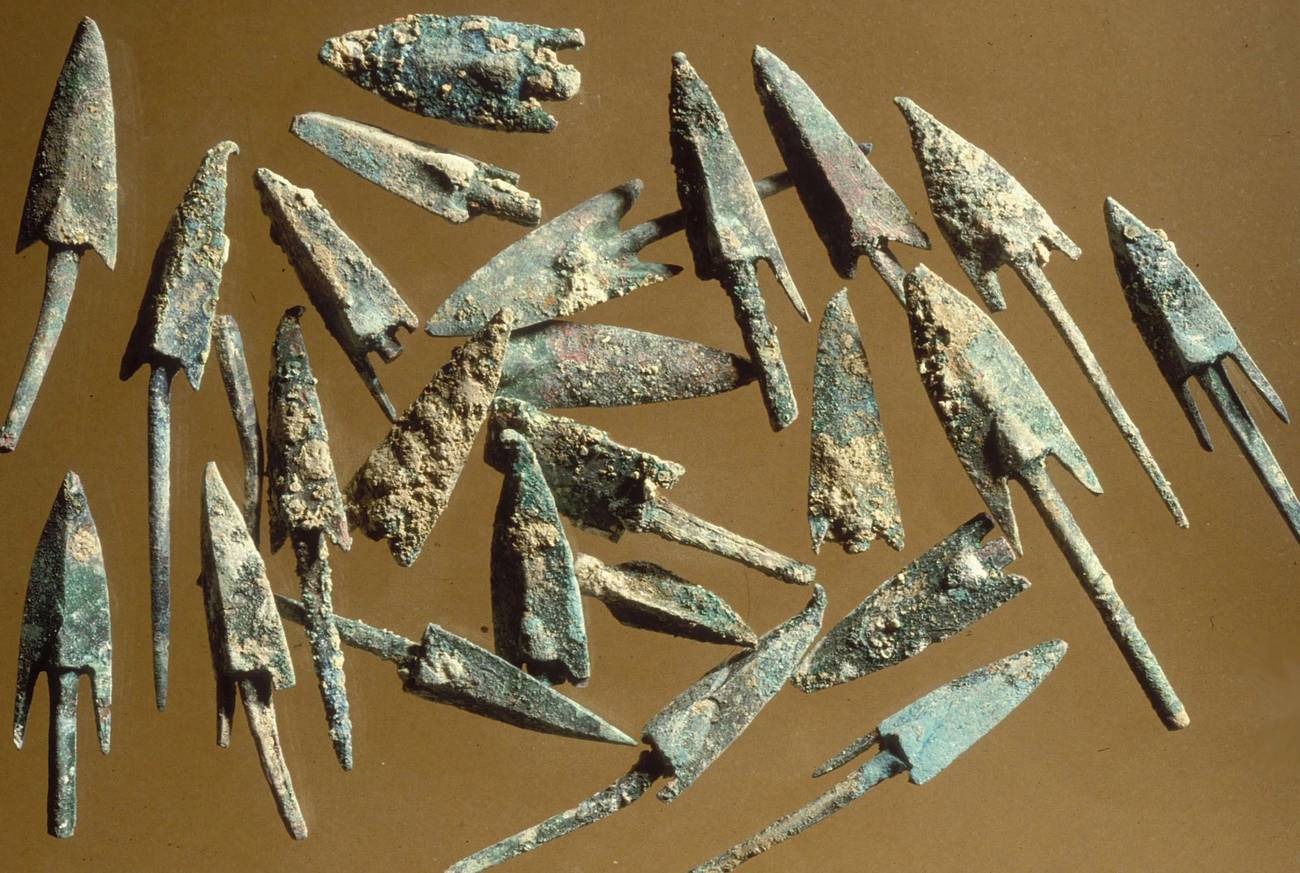

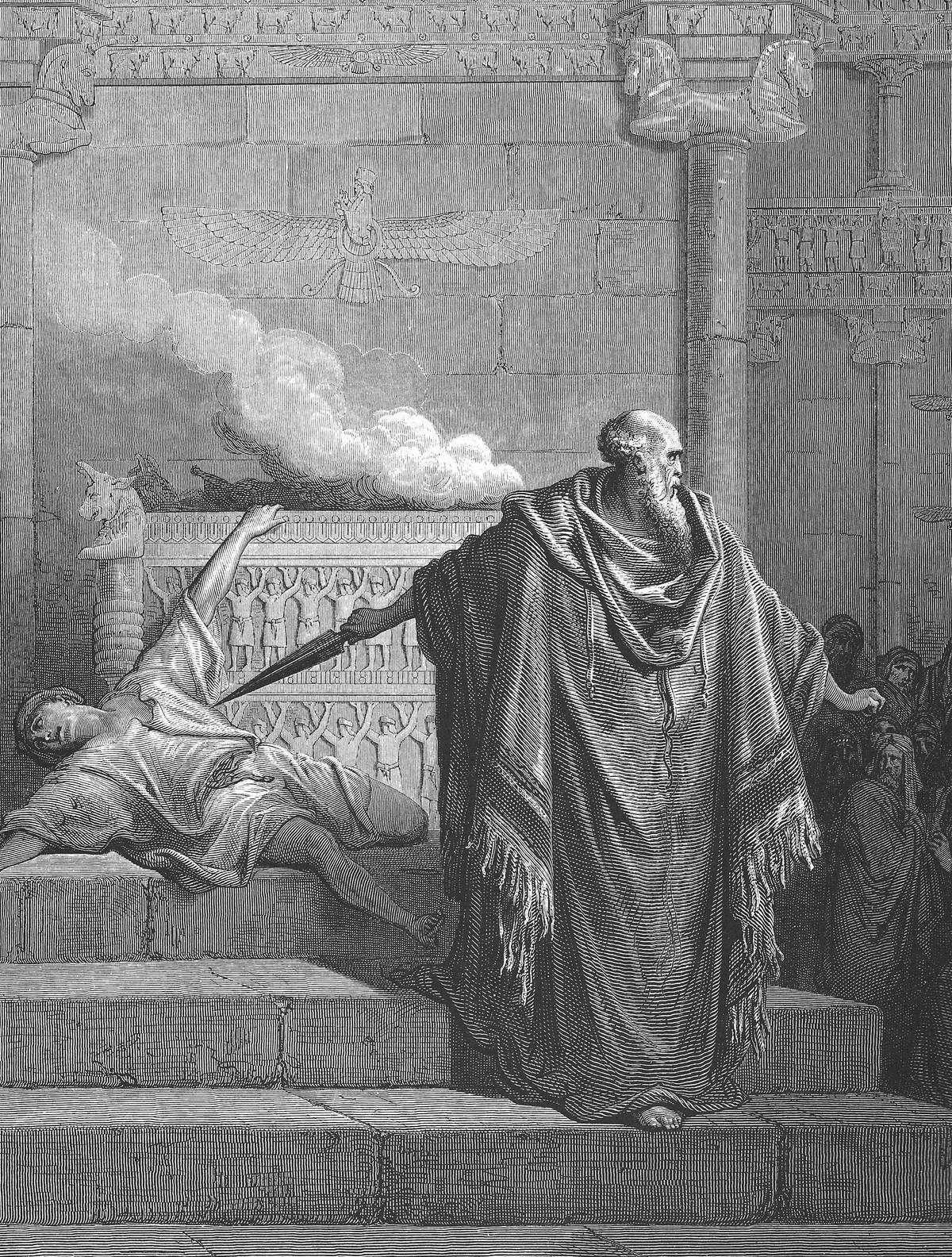

Under Antiochus IV Epiphanes (circa 215-164 BCE), the Seleucid government joined the ongoing civil war in Judea between the rural traditionalists and the Hellenizing urban elites. In 167 BCE, on Kislev 25, an altar to Zeus with swine sacrifices was erected in the Temple. Jewish practices, like circumcision, were banned, an act of totalitarian interference unheard of in the ancient world. The Seleucid government had no choice but to act together with Jerusalem’s Hellenizers against their rural opponents.

The result was the rise of the Hasmoneans, a family of rural priests. Mattathias/Mattityahu, a Jewish priest, and his five sons Yohanan, Shimeon, Eleazar, Yonathan, and Judah became the leaders of the traditionalist party; in 166 BCE, the father of the family died, and Judah replaced him as leader. The name of the dynasty, Hasmonean, in Greek Ἀσαμωναῖος, was said to derive from the name of the great-grandfather of Mattathias; however, it might derive from a Hebrew hapax used in Psalm 68.32

יֶאֱתָיוּ חַשְׁמַנִּים מִנִּי מִצְרָיִם כּוּשׁ תָּרִיץ יָדָיו לֵאלֹהִים

Where the Septuagint text has ēxousin presbeis ex Aigyptou Aithiopia prophthasei cheira autēs tō theō, “the priests will come …” (this Psalm can be read as composed under the Hasmoneans themselves). In Medieval and Modern Hebrew, חשמן is a Catholic cardinal, a priest: The root of the word חשמן might be Iranian for “evening” or “evening meal,” thus probably slang for “eater at the evening,” a reference to a priest.

In 164 BCE, on Kislev 25, the anniversary of the day that the Temple was desecrated three years previously, the renovation of the House (Hanukkah) was celebrated for eight days, being thus a substitute for the lapsed Festival of the Tabernacles. The Second Temple lacked those artifacts present in the original Tabernacle and in the First Temple, hence the stress on the Golden Menorah by the Hasmoneans.

The Hasmonean dynasty was established by Shimon Thassi, or HaTarsi, (r. 142-Febr. 135 BCE) who was the second son of Mattathias, the first leader of the revolt (Shimon’s name became the most popular Jewish name for centuries). In 141 BCE, a large assembly adopted a resolution “of the priests and the people and of the elders of the land, to the effect that Shimon should be their leader and high priest forever, until there should arise a faithful prophet” (1 Macc. 14.41). Two years later, the new state was recognized by the Roman Republic. Shimon conquered Beth-Tsur and Yafo/Yoppa and built the fortress of Adida (moshav Hadid); in February 135 BCE, he was assassinated in a conspiracy organized by his son-in-law and rival Ptolemy, son of Abubus. Shimon was succeeded by his third son, Yohannan/John Hyrcanus (r. 134-104 BCE).

Judeans were not the only headache of the shrinking Seleucid power; in the northeast, the Parthian tribes of seminomad Iranians in what is now Turkmenistan expanded southwards and westwards, and in 139 BCE, Demetrius II the Seleucid was defeated and even captured by the Parthians. Very soon, the Parthians led by Mithridates I controlled much of Iran.

Apparently, Judeans liked the Parthian expansion; members of the Hasmonean dynasty frequently had Iranian, more specifically, Parthian, names (Hyrcanus/Wirkān; Herod/Orodes/Wērōd). The vassal dynasties in Armenia, Cappadocia, and Pontus were threatening the Seleucid rule in Syria and northern Mesopotamia; the Parthians reestablished Iranian rule in Iran proper; the Romans were a threat.

In 133 BCE, the Seleucid ruler Antiochus Sidetes, called “the last great Seleucid king,” went to reconquest the former Seleucid possessions in the Iranian East supported by a Judean army under the Hasmonean prince, John Hyrcanus, but he was killed at the Battle of Ecbatana in 129 BCE. All of the eastern territories were then recaptured by the Parthians. The Maccabees were free again, and the Armenians began their expansion in central Anatolia bordering on Syria from the north.

Having begun as the leaders of the traditionalist party, the Hasmoneans developed rather quickly into typical Hellenist dynasts. In 96 BCE, the Sadducee Hasmonean king Alexander Yannai opened a bloody eight-year-long civil war against his more pietist Pharisee opponents, while using Greek mercenaries.

The Pharisees can be seen among the most Iranized Jewish groups of the Second Temple period; Mary Boyce considered the possibility that the very name of this sect means “Persianizers.” Although there are really very many problems with such an etymology, it seems to me a very plausible suggestion, in a meta-poetical sense. Josephus, after all, characterized this sect in the following way:

… when they determine that all things are done by fate [we would say by baxt or waqt; DSh], they do not take away the freedom from men of acting as they think fit; since their notion is, that it hath pleased God to make a temperament, whereby what he wills is done, but so that the will of man can act virtuously or viciously [compare Aboth 3:16, הכל צפוי והרשות נתונה, “everything is predestined while the freedom of choice is given to the mankind”; DSh]. They also believe that souls have an immortal rigor in them, and that under the earth there will be rewards or punishments, according as they have lived virtuously or viciously in this life; and the latter is to be detained in an everlasting prison, but that the former shall have power to revive and live again; on account of which doctrines they are able greatly to persuade the body of the people, and whatsoever they do about Divine worship, prayers, and sacrifices, they perform them according to their direction; insomuch that the cities give great attestations to them on account of their entire virtuous conduct, both in the actions of their lives and their discourses also.

Were we not told that this is a description of a Jewish sect of the Second Temple Period, we could be led to believe that the passage speaks of Zoroastrians, maybe even of those belonging to this or that Zoroastrian heresy.

The Hasmonean monarch Alexander Yannai tried to create a homogenous country in a place of great diversity. With this goal in mind, he used the same methods as the Jewish Hellenizers and their Seleucid patron Antiochus Epiphanes: in 85-82 BCE the territories east of Transjordan, Samaria, Galilee, and Idumea/Edom were conquered, with forced conversion of Idumeans and others to the Jewish religion.

Tigranes the Great of Armenia invaded Syria in 83 BCE, putting the Seleucid Empire virtually at an end. In 69 BCE, Tigranes invaded southern Syria having laid siege to Cleopatra Selene I in Ptolemais (Acre/Akko). In Judea, the pro-Pharisee Queen Salome Alexandra (r. 76-67 BCE) made efforts to appease Tigranes. A short time after having seized Ptolemais, Tigranes learned that Lucius Licinius Lucullus was devastating Armenia and had laid siege to his capital city, Tigranocerta, so he rushed back to Armenia. In 66 BCE, Tigranes withdrew his support from Mithridates the Great, the king of Pontus, and came to an accommodation with the Roman General Pompey, having lost all his newly acquired possessions.

Mithridates was defeated by Pompey in 63 BCE; the same year, Pompey intervened in the civil war in Judea between the Pharisee-supported Hyrcanus II (r. for three months in 67 BCE, killed by Herod in 36 BCE), and his Sadducees-supported younger brother Aristobulus II Yannai/Jannaeus (66-63 BCE), the sons of the anti-Pharisee King Alexander Yannai/Jannaeus (r. 103-76 BCE) and the pro-Pharisee Queen Salome. In 63 BCE, Pompey entered the Temple and restored the high priesthood to Hyrcanus. Thus, Judea came to become a part of the Roman-ruled world.

Under Roman patronage, client nations like Armenia and Judea continued with some degree of autonomy under local kings, but the Seleucid Syria was made into a Roman province. Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II, Shimon’s great-grandsons, became pawns in a proxy war between Julius Caesar and Pompey. The deaths of Pompey (48 BCE) and Caesar (44 BCE), and the related Roman civil wars, provided some breathing room for the Hasmonean kingdom, which was backed by the Parthian Empire, only to be crushed by Mark Antony and Augustus.

The sorrowful fate of the last Hasmonean king of Judea, Antigonus II Mattityahu/Mattathias the son of the aforementioned King Aristobulus II, is a manifestation of attempts of Judeans to rely on the Parthian support against Rome and of the Parthian failure to stand up against the Romans. Like his father, Aristobulus II, and his elder brother, Alexander II, who had been killed by the pro-Pompeian party, Antigonus was anti-Roman. When the Parthians invaded Syria in 40 BCE, Antigonus was able to gain the support of both the Judean aristocrats and the Pharisee party and made advances to the Parthians promising them gold and 500 slave girls, in addition to his loyalty.

The Parthians, ruled by Herod’s namesake, Orodes II (57-38 BCE), sent Antigonus troops 500 heavy-armored horsemen (according to the number of the slave girls?), and in 40 BCE, Antigonus was proclaimed king and high priest. Herod nearly escaped death at what is now Herodium (it was later built on the site to commemorate Herod’s miraculous salvation from the hands of the Parthians). The Parthians then sacked Jerusalem.

Our best source for Antigonus’ war against Roman domination is Josephus, but while reading Josephus about things Parthian we should remember that the author was a staunch supporter of Roman dominance. The first, Aramaic, version of Josephus’ Jewish War was written in this language specifically for the Jews of the Parthian realm; it was sent to them as propaganda, in order to dissuade them from revolting against the Romans. So, when Josephus wrote (Ant 14.14.6) that “Antigonus … was still in hopes that the Parthians would come again and defend him,” he was biased in favor of Herod the Great, who rose to power as an anti-Parthian and pro-Roman puppet king.

During three years, Antigonus led a fierce struggle for independence from the Romans (40-37 BCE), which lasted until his horrible death—he was said to be the first king ever to be crucified and scourged. It can be believed that the Roman treatment of Jesus, King of the Jews, whether real or just narrated, was a recapitulation of the treatment that the Romans—and their puppet, Herod—meted out to the last independent Jewish king.

The Hasmonean dynasty was mostly physically destroyed and replaced by Herod the Great in 37 BCE. Herod, a descendant of the forcibly converted Idumeans, tried to bolster his legitimacy by marrying a Hasmonean princess, Mariamne, by building the new Temple in place of the humble structure he had inherited from his Hasmonean high priests, the Temple of Herod, and by propagating a Messianic aura about himself (recorded, vaguely, in the New Testament). In 6 CE, the Roman Republic annexed Judea proper, Samaria, and Idumea into the new Roman province of Judea, and in 44 CE, the rule of a procurator was established side by side with the rule of the Herodian “kings” Agrippa I and Agrippa II.

Two of Herod’s other descendants—who were, most probably, also descendants of Tigranes the Great—were made kings of Roman Armenia, prompting thus the later legend of the Davidian roots of the Bagratid dynasty, with David’s harp added to the Bagratid coat of arms. Tigranes VI, son of Alexander (son of Herod the Great and Mariamne the Hasmonean) was the Armenian king under Nero (from 58 to 63CE). In 61 CE, he invaded Adiabene, the vassal kingdom of the Parthians populated by “proto-Kurds” and speakers of Aramaic, and deposed, for a while, Monobazes II, Adiabene’s Jewish king.

Monobazes II was a convert to Judaism, who ruled after the death of his brother Izates around 55 CE. He made donations to the Jerusalem Temple, as described at some length in the Talmud: “King Monobaz had all the handles of all the vessels used on Yom Kippur made of gold … He also made of gold the base of the vessels, the rims of the vessels, the handles of the vessels, and the handles of the knives” (Yoma 37a,b).

Monobaz II still sat on the throne of Adiabene during the Jewish War and assisted the Jewish rebels considerably. According to the Talmud, he “dissipated all his own hoards and the hoards of his fathers in years of scarcity. His brothers and his father’s household came in a delegation to him and said, ‘Your father saved money and added to the treasures of his fathers, and you are squandering them.’ He replied, ‘My fathers stored up below and I am storing up above ... My fathers stored in a place which can be tampered with, but I have stored in a place which cannot be tampered with … My fathers gathered treasures of money and I have gathered treasures of souls ...’” (Baba Batra 11a).

In the course of his war against Tigranes VI, Vologases made peace with Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo in 62 CE in order to install Tiridates I as King of Armenia, on condition that he travel to Rome to be crowned by Nero. At Rhandea, Tiridates laid down his diadem at the foot of Nero’s statue, promising not to resume it until he received it from the hand of Nero, himself, in Rome.

Tiridates’ nine-month-long journey to Rome in 66 CE left a great impression on the Romans and Hellenes. He traveled, while accompanied by Magi and by the children of Vologases, Monobazes, and Pacorus, in order to be crowned. While meeting the sunlit Nero in Rome’s Forum, Tiridates knelt, with hands clasped on his breast (which is an Iranian gesture of submission) and said in Greek:

“I am a descendant of Arsakes and the brother of the Kings Vologases and Pacorus. I have come to you who are my god; I have worshipped you as the Sun/Mithra.”

It was this peace with Parthia and Armenia which lasted for some 50 years (till 114) that allowed the Romans to deal with the Great Jewish Revolt that erupted just a year after Tiridates’ coronation in Rome.

These were two interesting centuries that determined the destinies of Jews, Armenians, Parthians, Romans and the world. The Parthians failed, to a great degree, because they were not skilled in the art of running a well-organized state. In religion, however, as we have seen, Iranian ideas, through the channels of Mithraism, Judaism, and Christianity, conquered the Roman conquerors.

Dan Shapira is an interdisciplinary historian and philologist at Bar-Ilan University. He is working currently on medieval and early modern Jewish minority communities, the Crimea, and the Khazars.