Plagues 10, COVID-19

We’re sick, and the meaning of this holiday seems more potent than ever

My husband got a call last week; he’d been exposed to the novel coronavirus. By last Thursday, three-quarters of my household (the cats don’t count) was ill.

I did a televisit with my doctor, telling her about my fever, body aches, dry cough, intense dizziness, and brain fog. “Yep, sure sounds like COVID-19,” she said, irksomely superchill. Her prescription: Stay home. Take Tylenol, not ibuprofen. Robitussin DM for coughs. Tons of rest and fluids. Do not try to get tested or go to the hospital. I am a Jew; I have faith in hospitals. But I listened.

By last week, by the day I called my doctor, New York City’s health care system was completely overwhelmed. Now it’s even worse: There are 33,000 confirmed cases in New York State as of today; 1 in 1,000 people in the metropolitan area have tested positive, a much higher “attack rate” than in other regions. New York state accounts for a quarter of the tests used in the country. There aren’t enough tests, masks, gowns, ventilators, hospital space. There’s a drive-through testing site in Staten Island, but we’ve been firmly discouraged from trying to go: People who are sicker than we are need it.

The New York City government’s instructions: “Unless you are hospitalized and a diagnosis will impact your care, you will not be tested. Limiting testing protects health care workers and saves essential medical supplies, such as masks and gloves, that are in short supply.” Having heard the horror stories from doctors, nurses, and other health care workers in the trenches, I have no desire to selfishly make their jobs harder and take needed resources from the profoundly ill. (However, every time I hear of a famous New Yorker who has tested positive but doesn’t feel that sick, I wonder, “How the hell did you get a test? Just how bratty were you?”) I realize it is not very Jewish to refrain from demanding something, but I understand that we need to look to our tradition’s values and worry about the people who need help more than we do.

Here are the things I didn’t know: The illness waxes and wanes. I felt way better on Sunday morning, then felt horrid again on Sunday night. (Really wish I hadn’t posted on Facebook that I was feeling better.) Different members of my family are experiencing different symptoms: Jonathan’s coughing the hardest; Josie is spiking the most frequent fevers and getting the worst headaches; I’m the most exhausted and achiest. Josie has that wacky symptom of lost sense of smell and taste; the rest of us don’t. Maxine, our superhero, remains symptom free, and maintaining a 6-foot social distance in a New York City apartment sucks. Max keeps wailing, “I’m touch-starved!” I get it. I have never wanted to hug a human being so badly. I know Jonathan’s and my parents are anxious to hug us, too, and vice versa.

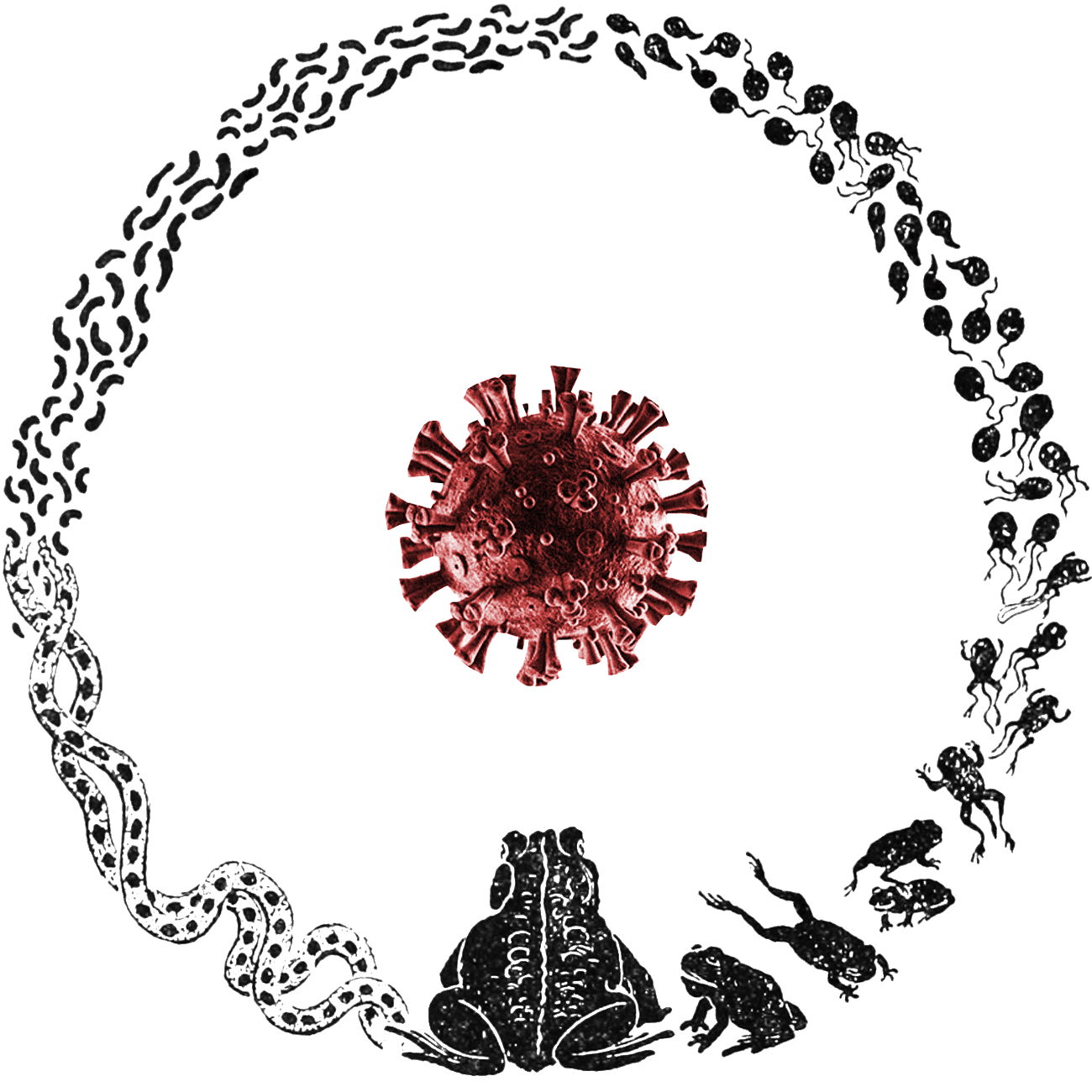

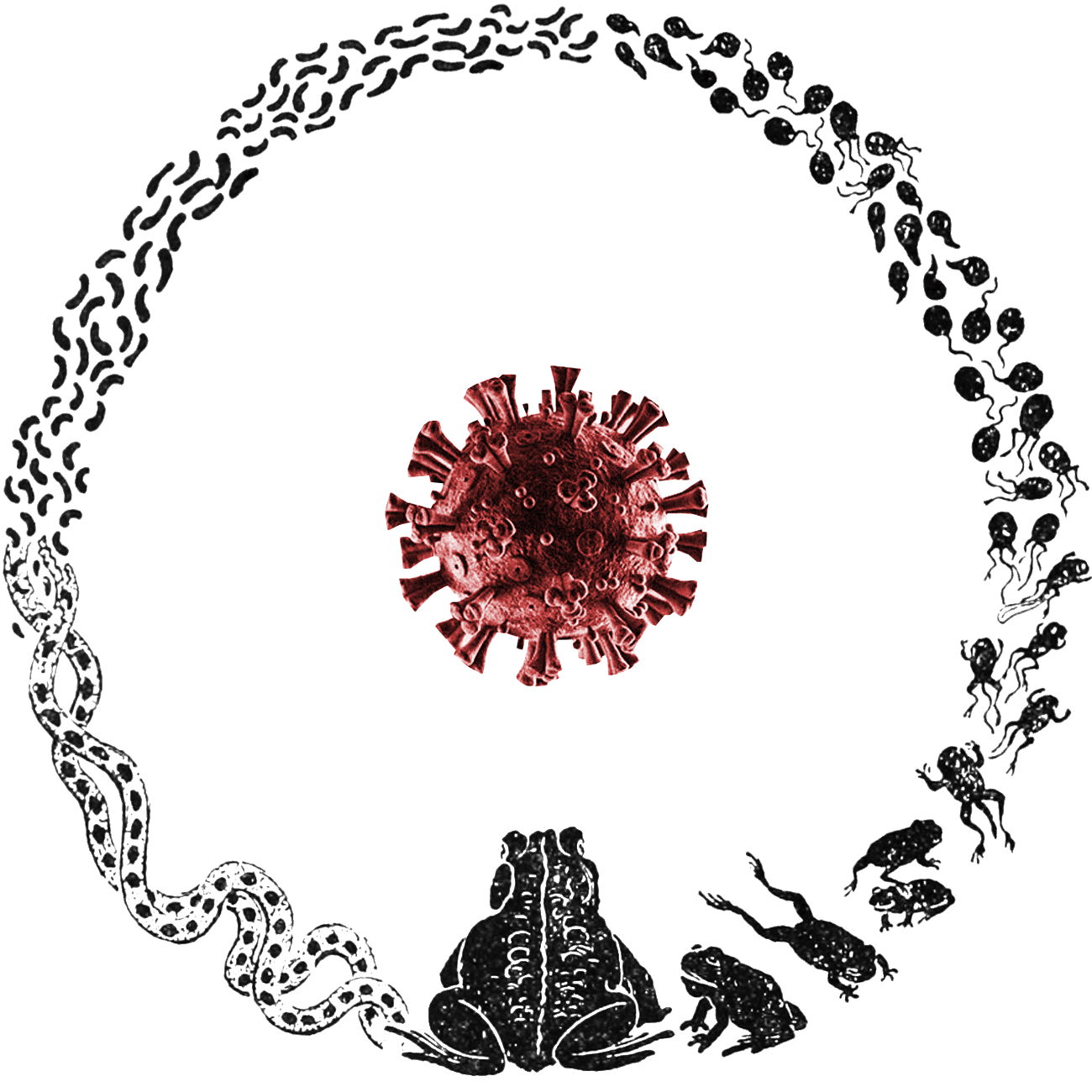

On Friday, a package I’d ordered weeks ago, containing dozens of tiny Seder frogs, arrived. I burst into tears. I had a plague-related decor vision for the Seder that I’m going to have to let go. I’m so exhausted right now, I can’t imagine even doing a pro forma Zoom Seder, let alone the kind of thoughtful, personalized, bespoke Seder I want to do every year.

I wrote a piece a few years ago about how Passover is a holiday that fetishizes perfectionism: Is your home as clean as it can truly be? Is that baking soda certified kosher for Passover by the proper authority, and not some crappy lesser authority? Is everyone at this table experiencing this Seder as a transcendent and emotional learning experience? Back then, I wrote about the notion of optimalism versus perfectionism: The former strives for a given experience to be its best self, while the latter is only satisfied with the best, period. But the best is always elusive. Imperfection should be part of the experience: The quirk, the wabi-sabi, the personalization, the kintsugi.

So this will not be the Seder I want. I won’t write a parody song or find an appropriate poem; the menu will be extremely curtailed since I get tired just standing for more than an hour.

I was planning to write something this week about strategies for hosting a Seder in the age of COVID-19. I was ready with jokes: Why is matzo the perfect novel coronavirus food? It lasts forever, fills you up, and causes the kind of constipation that requires very little toilet paper! What are the steps of the Seder this year? Kadesh, Urchatz, Karpas, Urchatz, Yachatz, Urchatz, Maggid, Urchatz, Rachtza, Urchatz, Motzi Matzah, Urchatz, Maror, Urchatz, Korech, Urchatz, Shulchan Orech, Urchatz, Tzafun, Urchatz, Barech, Urchatz, Hallel, Urchatz, Nirtzah! (Get it? Instead of two ritual washing steps, you wash after every step!) Ha ha ha ha sob. It’s hard to laugh when you’re very tired and very scared, and feeling dumb about being scared because you know you have it better than a lot of other people. This doesn’t feel like the right time for Seder standup.

More aptly, I was going to talk about Rav Irwin Keller’s linguistic musings on the word koved, which sounds so much like COVID. “Koved in Hebrew means heaviness, weightiness,” he writes. “And I feel the heaviness of the responsibility ahead of us—the responsibility not to panic, the responsibility to learn and help each other learn the ways to stay healthy. And I feel the weight of the not-knowing—not knowing how exactly this will unfold.” Further, he notes, koved in Yiddish means honor, respect. “And I am called to honor the complexity of the Creation we live in. This Creation in which uncountable species compete for space and survival, including the tiniest ones, who can sometimes take down the mightiest among us ... and on the other hand, to offer koved, respect, to the wonder of us, the wonder of humanity, that we are frail and vulnerable and as a result we create and we sing and we make beauty out of our frailty and we build community to be stronger together than we are on our own.”

A week ago, I wish I’d understood that this virus takes an unpredictable path. I thought when I felt better, it meant I was really better. But then I felt sick again. Not knowing is the hardest part, but it’s the part we have to sit with.

And then I watched an interview with Ritchie Torres, New York City’s youngest City Council member, who was diagnosed with the virus. He said, “I think of social distancing as much as a pattern of thinking as a pattern of behavior. We all should act as if we have tested positive. We all should act as if we are carrying the virus—and then adjust our behavior accordingly.” Doesn’t this sound like “B’chol dor vador chayav adam lr’ot et atzmo k’ilu hu hatza mimitzrayim”? In every generation, a person is obligated to see themself as if they were redeemed from Egypt? We hope to be redeemed from this pandemic; we hope that social distancing will be our sign upon our doorpost telling the virus to skip our house; we hope to be suitably grateful for our lives even as we mourn the gift of hugging.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.