No Holiday for Soft Men

Purim’s bloody story of vengeance is a necessary reminder about how justice really works

Rambo: First Blood Part II came out in Israel when I was 10, and ever since I saw it I wanted two things and two things only: a cool, red headband, and a big, shiny gun. Neither struck my parents as particularly reasonable, and so I waited a few months until Purim drew near and then, ever so casually, told my mother that this year, I’ll be dressing up as my hero, the world’s most pectorally impeccable Green Beret.

When the big day came, I smeared some shoe polish under my eyes for effect, tied the coveted band around my head—doing my best to ignore the fact that it was really just a silk sash my mother had removed from one of her dresses, a misfortune that would have never befallen the real Rambo—grabbed the toy gun, and went to school.

Purim, in Nof Yam elementary, was a festival as sweet as it was predictable. You’d spend two hours pretending like it was a normal school day, doing your best to listen while furtively eyeing the small pile of mishlo’aĥ manot that each kid had brought from home. As the teacher carried on, you’d try to figure out which of the cellophane-wrapped treasures will end up yours, and prayed softly that you’d receive one of the nicer baskets prepared by one of the more attentive girls rather than some chaotic platter thrown together by an inattentive boy and containing little more than a pair of hamantaschen and, if you were lucky, a small bag of Bamba.

I was still looking at the goods when the teacher embarked on another one of the day’s customs, the reading of the Megillah. I had heard it so many times before, and so tapped my desk impatiently, wishing that Queen Esther had conducted her business in one nightly feast for the king and Haman rather than two. And then, out of the trill of the familiar, popping out of the Megillah like the tip of an iceberg out of a dark ocean, came the following words:

And the rest of the Jews who were in the king’s provinces assembled and protected themselves and had rest from their enemies and slew their foes, seventy-five thousand, but upon the spoil they did not lay their hands on the thirteenth of the month of Adar, and they rested on the fourteenth thereof, and made it a day of feasting and joy. (Est. 9:16–17)

Pretending to be John Rambo was one thing; munching on poppy-filled pastry while nodding contently to a story about the joyous massacre of scores of civilians over not one but two days was another. I put my gun down. All of a sudden, my favorite holiday felt a lot less kid friendly.

Over the next few decades, I continued to be haunted by the specter of Purim. And, the more I read, the less lonely I felt. That bit about the slaughter, I learned, had troubled Jews since at least Victorian times: Ellis Abraham Davidson, a prominent educator and writer, was entrusted with publishing a version of the Hebrew Bible that would introduce its riches to the gentiles from a Jewish perspective, and ended up cutting most of the stuff about the slaughter. His contemporary, Claude Goldsmid Montefiore, a darling of Balliol College, Oxford, was equally as repulsed by Purim, and, in his own version of the Hebrew Bible, apologized to his readers for that messy business of bloodletting. “We can hardly dignify or extenuate the operations of the Jews by saying that they were done in self defense,” he wrote. “For we are told that all the officials helped the Jews, and that none durst withstand them. Moreover, the slain apparently included both women and children. There is no fighting, but just as there was to have been a massacre of unresisting Jews, so now there is a massacre of unresisting gentiles.” In his landsmen’s defense, Montefiore simply argued that he very much doubted that any Jew celebrating Purim really understood what it was he or she were celebrating. And, ever the gentleman, he expressed his wish that the odious holiday “were to lose its place in our religious calendar.”

Purim, thankfully, persisted, and with it the discomfort of many enlightened Jews eager to explain away its hard kernel. Shulem Deen, a gifted writer and former Hasid, has credited the holiday for accelerating his decision to leave Orthodoxy’s fold; “I wanted a world,” he wrote, “in which seventy-five thousand dead makes one shudder, if ever so slightly, before enjoying hamantaschen and whiskey.” And Rabbi Dr. Haim Burgansky, a Bar Ilan University professor, gave his own midrash on Purim, suggesting that the real reason we fast on Ta’anit Esther was merely to mourn for all those innocent souls plucked by Mordechai’s murderous minions.

These exegeses ought to have moved me. They strummed on the very same tender string in me that shuddered at the song of slaughter. Instead, these apologias merely drove me back to the text itself, back to chapter 9 of the Megillah, aching to understand just why my heroes took so gleefully to carnage.

Read the story as pure peshat, and you’ll be left with a sour aftertaste, cringing at the cruel symmetry between Haman’s genocidal plan and the Jews’ eventual retribution. You may not mind much the suspension of the Agagite and his boys—these baddies had it coming—but you’ll probably wonder why the famous Jewish quality of mercy failed to materialize and spare the pitiful Persians their lives. At the very least, you’ll ask, like Montefiore, why we enlightened moderns continue to celebrate this bloody holiday with such vigor, a question, sadly, not too frequently or eloquently addressed.

Of course, the answer is right there in the Megillah, rewarding, as Jewish texts always do, a patient and layered reading. Go back to chapter 3, and you’ll see Haman as a menace in full. Slighted by Mordechai, he could easily have applied his might as the viceroy of a great empire and crushed his foe. Had he done that, Haman would’ve been a familiar figure to readers of ancient tales, a prideful hothead who lets his hubris have the best of him.

But the Agagite isn’t a hothead. He waits until his wrath is distilled into potent fuel, and then carefully constructs his operatic bloodshed. He draws lots and makes plans. And it’s not just Mordechai he seeks to annihilate but all Jews everywhere.

Why? The Megillah (3:6) simply states that it was “contemptible to him to lay hands on Mordechai alone,” which may be the key to unlocking Haman’s terrifying theology. Exterminating the Jews isn’t just a way to sate his lowly appetites; it’s an affirmation of his warped worldview, in which power may rest solely with one source, and all who question or oppose or complicate it in any way must die.

And Haman said to King Ahasuerus, “There is a certain people scattered and separate among the peoples throughout all the provinces of your kingdom, and their laws differ from [those of] every people, and they do not keep the king’s laws; it is [therefore] of no use for the king to let them be.” (3:8)

They have different laws, therefore it is of no use to let them be: The same words might’ve been spoken by Hitler’s goons or Stalin’s thugs, but they continue to resonate today with America’s young and educated and self-assured who brook no dissent and tolerate no divergence from dogma. In newsrooms and classrooms and boardrooms, many view the world just as Haman once had, a perennial struggle between the blamelessly good and the irredeemably evil, a struggle that can only conclude if the good achieve absolute power and use it to wipe evil out.

This, hallelujah, is not the Jewish idea of justice. We’ve no foes that call out for an a priori pogrom. Not even Amalek. As the Israeli scholar Rabbi David Levy wisely reminds us, what makes the Bible’s commandment in Deuteronomy 25:19 to wipe out Amalek’s memory difficult is that it’s rooted in the duty of memory. We are obligated to wipe out the Amalekites not because they’re an abstraction, a convenient catchall for all that we find distasteful and challenging, but because they are the perpetrators of a specific act against a specific people under specific circumstances. It’s their actions that make them odious, not their essence. The same is true with the Persians felled by the Jews on these two days in Adar so long ago: They died not because they were a faceless Other, but because they had prepared to join Haman, an Amalekite by descent and deed, in his vicious plot.

Still, why murder? No crime, after all, had been committed; none of the mob that would have annihilated the Jews did as much as pick up a pitchfork. Why kill so many, and then ask for an additional day to kill yet more?

To begin and answer this question, Rabbi Levy reminds us of an apparently paradoxical condition during ancient times: the more murders plagued the Jews during mishnaic times, the less inclined the Sanhedrin was to judge the murderers. This, he writes, is because God’s law isn’t and should never be a mere deterrent, a blunt instrument of justice; instead, it’s a path for the righteous to follow, and if so many people choose to abandon it there’s little anyone can do to make things right. But if you witness an aberration so shocking as Haman’s—his plot, we’re told in Esther 3:15, was so heinous and so out of the ordinary as to dumbfound his fellow Shushanites—you’re commanded to act forcefully so as to make sure that it doesn’t take hold and become the new normal. Seen in this light, revenge, Rabbi Levy writes, “expresses the people’s healthy existence; it’s a saying that the people will not tolerate any attempt to harm their own.” This is why we should always remember the villainy of Amalek: To forget it is to say, however implicitly, that killing Jews is permissible, forgivable, and recurrent.

Here, then, is the moment that the Purim story transcends from a gritty tale of revenge to a benevolent if bloody expression of morality. Unlike Haman, Mordechai and Esther insist that guilt isn’t transitive but personal; it applies only to those who have transgressed, not to all members of a group, race, nation, or class. Unlike Haman, Mordechai and Esther are interested neither in power nor in riches but in justice—again and again we are reminded that the Jews refused to partake in the spoils, leaving the property of their vanquished foes unclaimed. And unlike Haman, Mordechai and Esther do not take the killing lightly: Their campaign is motivated not by personal considerations or calculations but by the desire to uphold what ought to be the foundation of every legal system anywhere—the principle that actions have consequences. To let the Persian plotters go unpunished, then, would’ve meant not only dismissing an attempt against the Jews as pardonable, but would have also dismantled the foundations of lawfulness and righteousness throughout the empire by showing that one may very well try one’s hand at genocide and walk away unscathed.

And here, too, is where Mordechai and Esther’s story shakes off the dust of antiquity and breathes new life into our tortured American moment. You needn’t be a particularly astute political observer to notice that the Land of the Free is having its Hamanite moment: Cadres of powerful men and women—professors and journalists, pundits and CEOs, lawmakers and tastemakers—are rising to advocate that we abandon America’s great promise of regarding all as equal and demanding instead that we regard our fellow citizens not as pieces of one cohesive and gorgeous mosaic but as stratified tribes perennially at war, some inherently privileged and sinful and others eternally virtuous and oppressed. And while these vicious viceroys, thankfully, don’t cast lots and sign death sentences, they are busy feeding anyone and everyone who dares defy their logic to cancel culture, that punishing machine that robs the innocent of their hard-earned possessions, from income to companionship. These joyless Jacobins are everywhere busy toppling statues of America’s founders, denouncing its myths and symbols as monuments to oppression and greed, and accusing opponents of thought crimes. They are assembled under the banner of social justice, but are neither particularly social nor especially just. Instead, they dream, like the Agagite, of having the power to suppress those who refuse to bow before them. Their ultimate goal is power, and their theology is one of division and replacement: For their truth to burn bright, all others must be extinguished. Succumb to their demands, and America will be America no more, just as Persia would’ve surely perished had Haman had his way. A great empire, as America proved in its own ferocious Civil War, isn’t one in which human beings can be doomed for no other reason than belonging to the wrong race, caste, religion, or class. A great empire is one that sets clear the laws and exacts a price of anyone who blatantly subverts them. And anyone who feels particularly gloomy about America’s future odds should recall that Mordechai and Esther, too, rose from lowly and marginal subjects to viceroy and queen, remaking the kingdom for the better and undoing the dark legacy of the murderous and divisive Haman.

You could end your reading of the Megillah there and still feel confident that Purim is far from the primordial celebration of unchecked retribution it is so often and so wrongly understood to be. But the Megillah offers us one more layer of meaning, this one pertaining not to the collective, national drama but to our own personal responsibility. To ask what we must do to hasten a brighter American future and dispel the darkness of our current political moment, we must once again look at Esther and Mordechai, and read their story again, this time as a mystical parable about redemption that urges all of us—Americans, Jews and non-Jews alike—to have the courage of our convictions as Mordechai did when he harshly assured Esther that if she failed to play her part, “relief and rescue will arise for the Jews from elsewhere” (4:14).

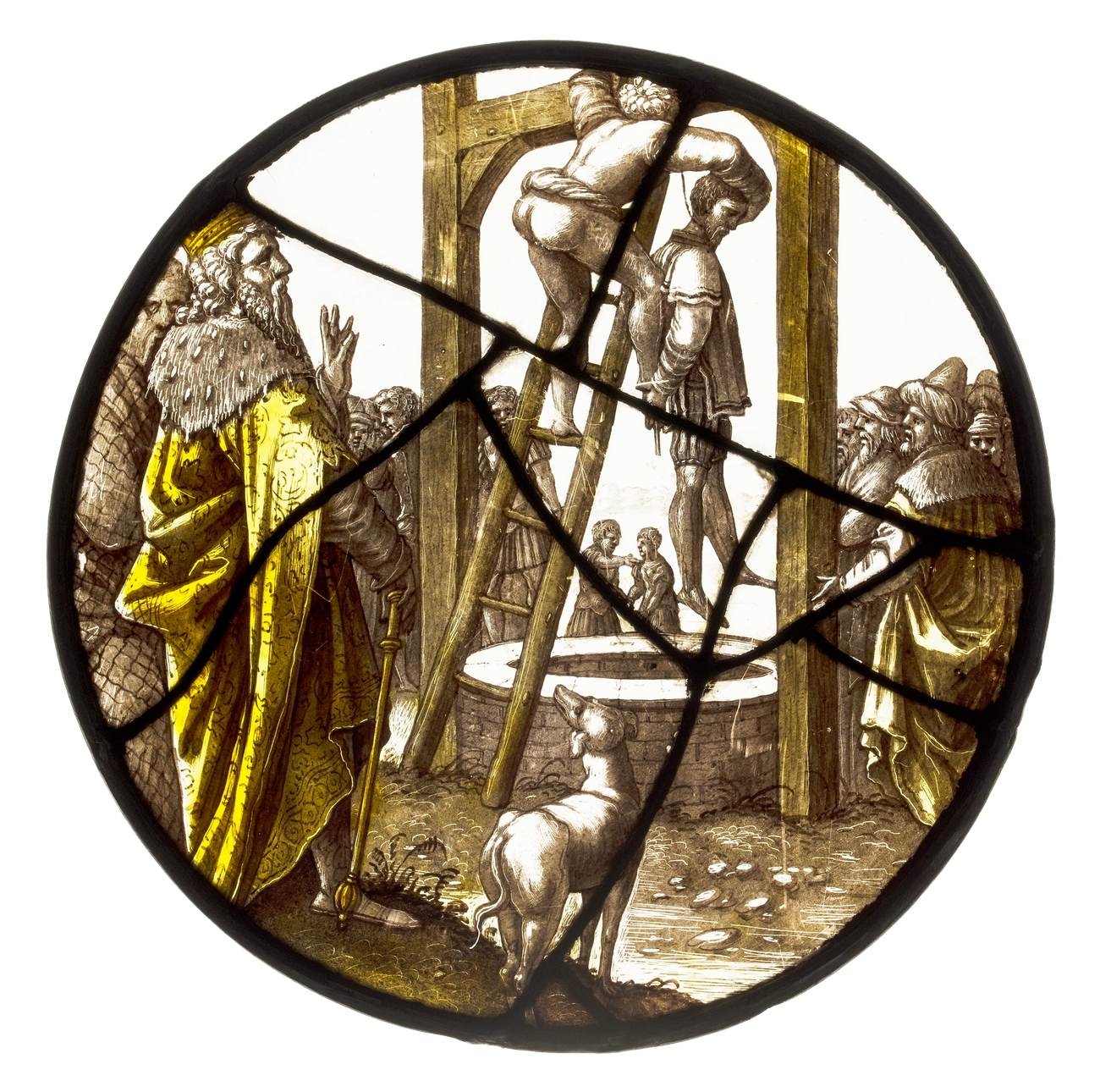

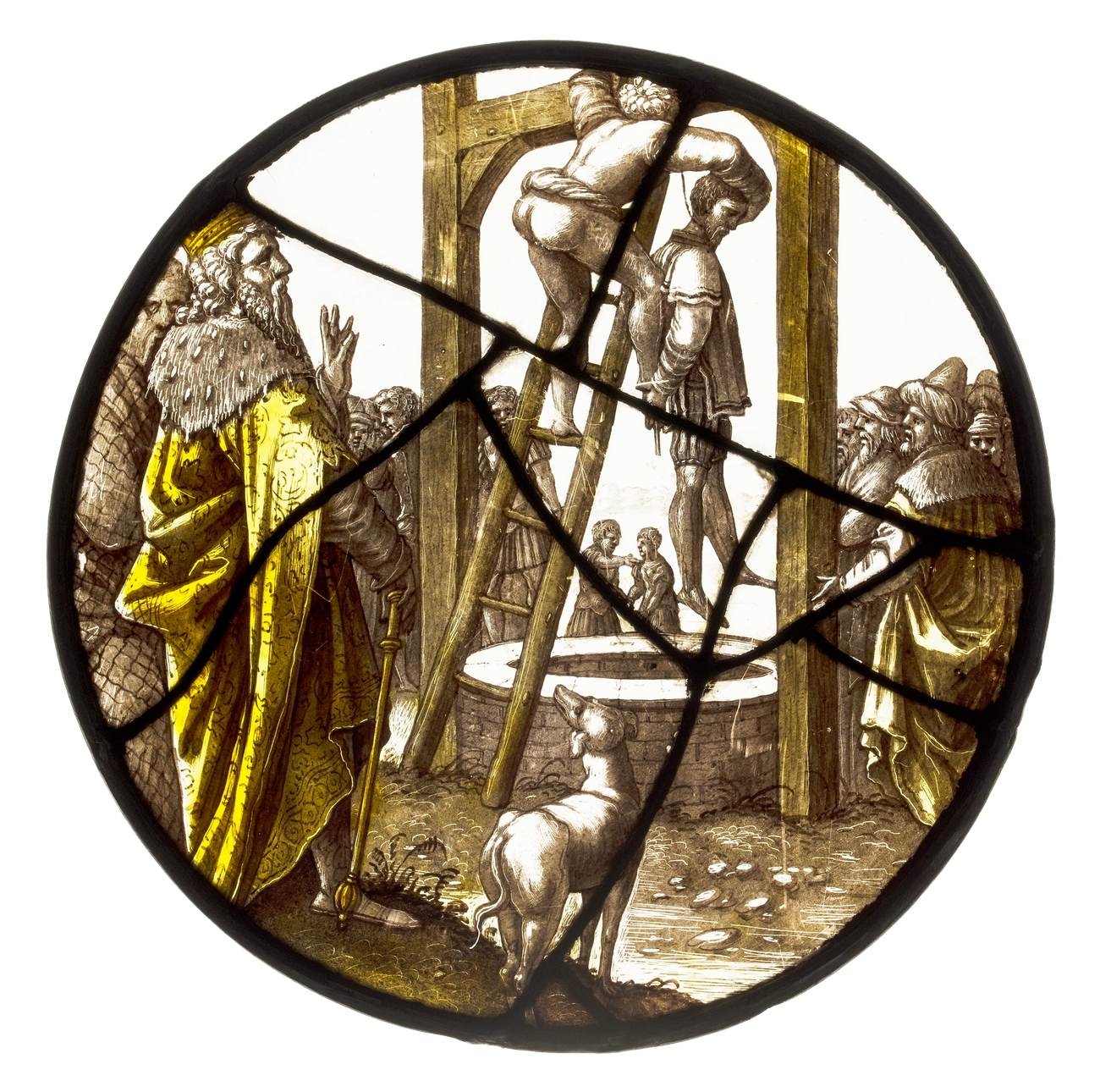

To illustrate this point—the story of the Megillah as a parable, urging us to always remain vigilant, reject the black bile that too often threatens to drown out hope and good cheer, and work tirelessly toward redemption, our own and the world’s—we’ve a strange yet compelling story about the Purim’s tale’s two leading men. Haman and Mordechai, the midrashic collection Aggadat Esther (5:9) tells us, weren’t random passersby who bumped into each other on the streets of Shushan; they were ancient acquaintances whose feud traced back to the building of the Second Temple, with Mordechai having been an industrious builder and Haman a wicked disrupter determined to postpone the work and hamper the Jewish people’s spiritual well-being. And not the Jewish people’s alone: The Temple, Isaiah reminds those who have forgotten, was built as a house of prayer for the whole world, a place where the word of God would flow forth as the water covers the sea (Is. 11:9). It was the earthly embodiment of the divine presence, a reassurance that there’s more to life than the pursuits of the flesh and that God’s law is more intricate and merciful than the naked power that mortal rulers so desperately seek. By disrupting the Temple’s building, then, Haman was getting in the way of mankind’s spiritual well-being, jeopardizing, in pure Amalekite fashion, the tenets of universal justice and the possibility of human flourishing for his own perverse purposes.

The struggle between Mordechai and Haman, then, neither begins nor ends in Shushan. It’s an eternal struggle between those whose faith leads them to see others with dignity and compassion, and those whose resentments drive them to all forms of tyranny. It’s the struggle between those who wish to uphold the legacy of Washington and Jefferson, Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King Jr., and those who want to replace it with 50 shades of censorship. And it’s the struggle between those who see it as their duty to personally strive to repair the world by adhering to the timeless tenets of justice and those who lazily expect the work of redemption to be done immediately and by the power of their social media demands.

The Jews, Tractate Megillah (12a) reminds us, were subjected to the schemes of Haman because they had partaken in Ahasuerus’ feast; instead of exercising their spiritual destiny and returning to help rebuild Zion, they warmed up to foreign customs, abandoning their own sense of destiny and purpose. Mordechai’s mission, then, was to awaken their spirit, to win the battle not only against Agagite-led enemies of flesh and blood but also against complacency, against lazy lack of belief in the power of personal commitment. Our mission, here and now in America, is not that different: We’ve gotten comfortable in the decadeslong feast of the 20th century, letting go of our distinctions and loosening our observances. Now that the nation is thick with Agagites, however, it again needs the Jews, forever the moral minders of sclerotic empires, to shake off the cobwebs of complacency, reread the ancient stories, and remind us of the enduring relevance of foundational values.

We must remember, as Rabbi Levy urges us, that there will always be those—like Haman, like Amalek—who will prey on us in our moment of weakness, when we’re tired or numb or just eager to enjoy a drink and forget all about the turbulence of fate. When that happens, we have but one obligation: fight, not only against the would-be oppressors but against oppression itself, against the idea that we’re powerless to chart our own course and demand our own rights. Fight against those who deny America’s godly promise. Fight against those who deny the Jews their safety and security. Fight against those who see the world as an everlasting war between two immovable camps. Fight against the cynics and the cowardly. Fight against those who wish to replace a cohesive community with warring tribes. Fight against those who urge you to remain silent because only other members of other tribes have the moral right to speak. They are all one and the same, a million little Hamans; we must reject them all.

In the very opening of his majestic interpretation of the Megillah, the Vilna Gaon sets the tone for what’s to follow by insisting that the story we’re about to read “hints at the trials of mankind, its war against the Evil Inclination, and the eventual downfall of the Devil.” Forget Milton, or, for that matter, Rambo: For a tale of wrestling with evildoers and evil itself, for a confirmation of will and wonder, for a call to personal responsibility and communal solidarity, look no further than Purim, the greatest Jewish story ever told.

Excerpted from the newly published Esther in America, edited by Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.