Reasons to Forgive—or Not Forgive

Understanding our societal addiction to forgiveness stories

It’s telling that our culture loves stories of Holocaust survivors forgiving Nazis, of rape victims forgiving rapists, of Black families forgiving the white murderers of their children and siblings. What all these stories have in common: They’re all about people with less power forgiving people with more power.

Our addiction to these narratives is problematic because these narratives enforce the status quo. They make us feel better about a world rife with inequality and injustice. We’re not saying that no individual victim should ever forgive the person who harmed them. People have free will. If forgiveness is healing for them, it’s not on us to tell them they’re wrong. It is, however, on us to tell each other that celebrating these stories can be a feel-good choice that mutes our obligation to look hard at what needs to be fixed in the world we live in.

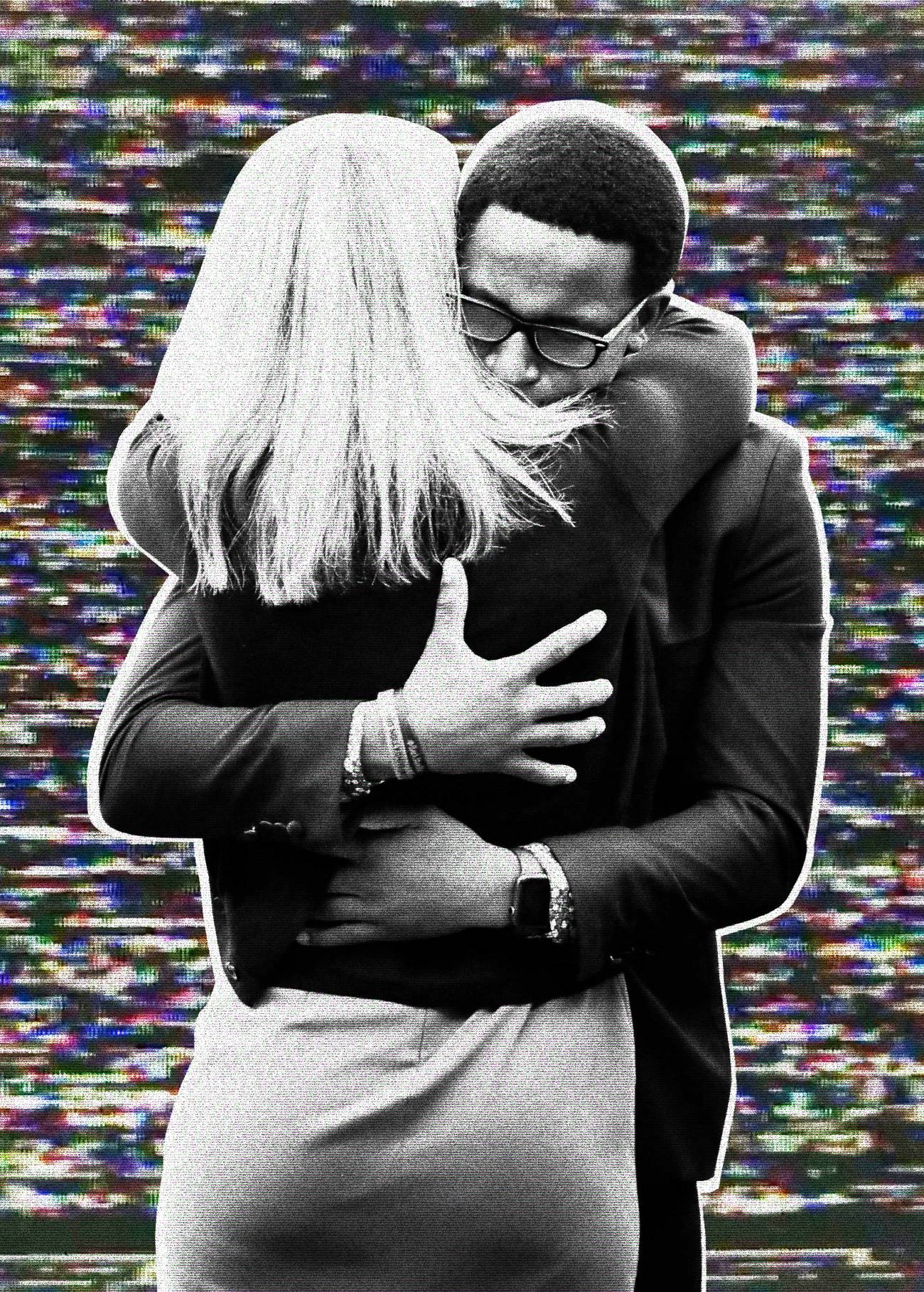

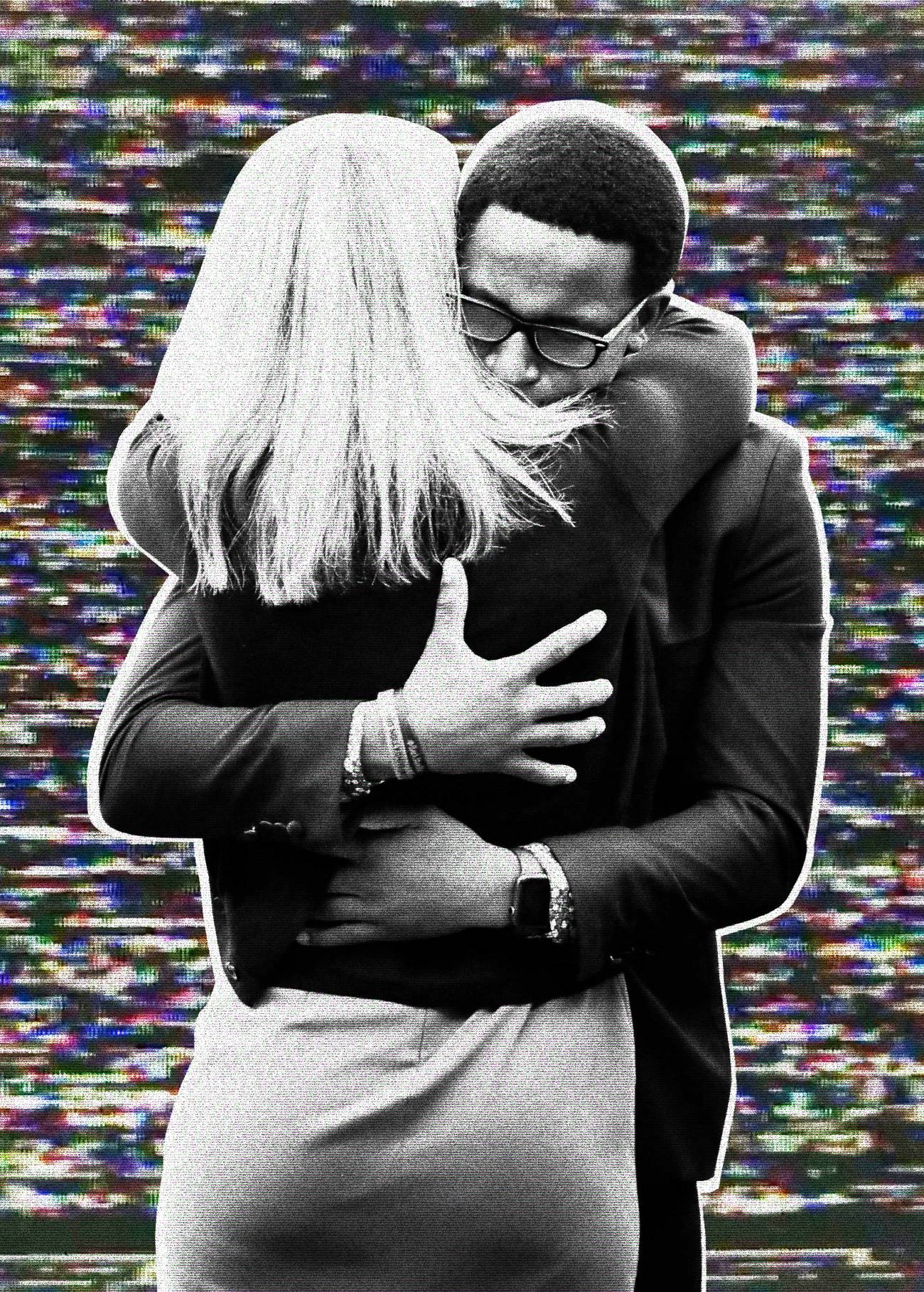

When Brandt Jean, the brother of Dallas police shooting victim Botham Jean, told his brother’s killer, former police officer Amber Guyger, that he forgave her, and gave her a big hug in the courtroom, the press celebrated. But when a relative of a murdered Black person reacts with anger instead of hugs and sweet biblical sentiments, the public response is often furious. For example, after the New York City police officer who killed Eric Garner with an illegal chokehold apologized, a reporter asked Garner’s widow, Esaw, whether she forgave him. She responded “Hell, no!” and a national news headline accused her of “Lash[ing] Out at Cop.” But that “Hell, no” was completely justified. Anger in the face of injustice is warranted.

Yolonda Y. Wilson, a philosophy professor at St. Louis University who researches government obligations to rectify historic and continuing injustice, wrote in 2019:

If anger can help us understand our place in the world and drive us to make the world that we occupy better, then good for anger. The most important feature of anger, properly directed, is the recognition that a wrong has occurred. To the extent that one’s anger motivates one to right wrongs, anger can be a tool of achieving justice. In this sense, anger is also tied to self-respect. Anger is a recognition that one is deserving of just treatment and that one is willing to demand just treatment, even if the demand is ultimately unsuccessful.

Eva Mozes Kor, a Holocaust survivor who in 2015 very publicly forgave a Nazi, has been celebrated as a hero. She was among the many pairs of Jewish twins upon whom Dr. Josef Mengele did terrible medical experiments. Fifty years after World War II, she connected with a Nazi doctor who’d worked at Auschwitz. At her urging, he wrote a letter of apology; she then wrote him a letter of forgiveness. A short BuzzFeed video about her has been viewed almost 200 million times. How noble! How marvelous!

The fuller story: Kor, who’d long spoken to schools and synagogues about the Holocaust, decided that for the 50th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz she wanted to reach out to a former Nazi doctor she’d seen in a documentary that she’d also appeared in. She said she wanted him to write that letter as proof to future generations that the Holocaust was no myth or exaggeration. The doctor did as she asked, writing, “I am so sorry that in some way I was part of it. Under the prevailing circumstances I did the best I could to save as many lives as possible. Joining the SS was a mistake. I was young. I was an opportunist. And once I joined, there was no way out.”

This is a terrible apology. It doesn’t take responsibility. It doesn’t offer specifics (“in some way I was part of it”). It offers excuses (“I did the best I could” and “I was young”). The doctor did have a choice. Other “young” (and even old) people joined the resistance, hid Jews in their basements and attics and barns, even elected to stand by passively without actively taking steps to join the Schutzstaffel, the top-tier political soldiers of the Nazi Party, as this doctor did.

Kor, however, was happy with the apology. And if she was happy, who are we to argue? Forgiveness is a choice.

A decade later, Kor also forgave Auschwitz’s accountant. She publicly held his hand and graciously allowed him to kiss her cheek. She wrote a book, The Power of Forgiveness, which came out in 2021 (she died in 2019, but a colleague at her private museum in Terre Haute finished it in her name). In the book, she describes her healing process: She wrote down all the bad words she wanted to say to Dr. Mengele, and once she ran out of words, she realized she’d also run out of anger; she was able to forgive. She decided to write a letter.

I, Eva Mozes Kor, a twin who as a child survived Josef Mengele’s experiments at Auschwitz fifty years ago, hereby give amnesty to all Nazis who participated directly or indirectly in the murder of my family and millions of others.

I extend this amnesty to all governments who protected Nazi criminals for fifty years, then covered up their acts, and covered up their cover up.

I, Eva Mozes Kor, in my name only, give this amnesty because it is time to go on; it is time to heal our souls; it is time to forgive, but never forget.

She asked the United States, German, and Israeli governments to stop investigating Nazis and to open all their files to survivors so they could perhaps read about what had been done to them and learn useful information for their medical records. (Her twin, who had also survived, had terrible health problems; it would have been helpful to know what substances had been injected into her body.) Kor read aloud on the ramp to the gas chambers at Auschwitz:

I am healed inside, therefore it gives me no joy to see any Nazi criminal in jail, nor do I want to see any harm come to Josef Mengele, the Mengele family or their business corporations. I urge all former Nazis to come forward and testify to the crimes they have committed without any fear of further prosecution. Here in Auschwitz, I hope in some small way to send the world a message of forgiveness, a message of peace, a message of hope, a message of understanding.

The press and public ate this up. But just as the footage of Brandt Jean hugging and forgiving his brother’s killer dismayed plenty of Black people, Kor’s actions horrified many other Holocaust survivors. As Holocaust scholar Deborah Lipstadt noted, “I watched them grimace as audiences gave her standing ovations and the media described her as someone ‘who found it in her heart’ to forgive, the implication being that survivors who did not follow her lead were unable to rise above their resentment. Survivors told me they felt they were being depicted as hardhearted, while Kor was being celebrated as the hero, someone bigger than they.”

In her book, Kor says she did her forgiving in her own name only ... but calling for amnesty for Nazis can’t be considered acting merely for herself. “I know that most of the survivors denounced me, and they denounce me today also,” she says in the video. “But what is my forgiveness? I like it. It is an act of self-healing, self-liberation, self-empowerment. All victims feel hopeless, feel helpless, feel powerless. I want everyone to remember that we cannot change what happened ... but we can change how we relate to it.”

This is absolutely true. In the book, Kor elaborates on how forgiveness made her “free to discover that I had power over my own today and tomorrow, again and again. It hurt no one, it doesn’t hurt me. And it is free. Everyone can accomplish it.” She then adds, “Also, there are no side effects. It works. But if you do not like feeling like a free person, it is possible to return to your pain and hatred anytime.”

Our addiction to these narratives is problematic because these narratives enforce the status quo. They make us feel better about a world rife with inequality and injustice.

This statement was beautiful until that last sentence ... which is a tad reductive, judgmental, and dismissive. Make no mistake, choosing to forgive can absolutely be therapeutic. Kor’s strategy of writing a letter to someone who harmed you, calling them all kinds of names, and then never sending the letter could work beautifully for some people. But her insistence that it will work is simplistic. To a woman who was raped and found it impossible to forgive her rapist, Kor suggested, “Write the letter again. And again. There’s no limit. Maybe you need to write it 10 times, maybe 20. You might even need to write 100 letters.” Couldn’t this prove more hurtful than helpful for some survivors of trauma?

Kor’s suggestions that gardening and spending time with animals can help people heal is also positive, also likely to be helpful to lots of readers. But again, the notion that these activities can lead everyone to forgiveness is facile.

People want to admire Kor and to find her generosity of spirit beautiful, because we want to live in a just world. We love cute, tough-talking old ladies with hearts of gold who remind us of our Bubbes and Bibis and Nanas and Nonnas. They charm us. They make us feel safe. They’re familiar, like the cast of The Golden Girls. They convince us that the world has changed for the better since the Holocaust. (Feel free to substitute “since slavery.” Or “since that rapist realized the error of his ways and cried on camera.”) The danger lies in wanting Kor’s story of forgiveness to be every victim’s story, and blaming the victim who refuses to conform to her narrative.

Forgiveness is indeed a choice. But so is refusing to respect the choice of people who have valid reasons not to forgive.

Excerpted from SORRY, SORRY, SORRY: The Case for Good Apologies by Marjorie Ingall and Susan McCarthy. Copyright © 2023. Reprinted with the permission of Gallery Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.

Susan McCarthy is the coauthor (with Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson) of the international bestseller When Elephants Weep and the author of Becoming a Tiger. Her work has been anthologized in The Best American Science Writing.