Why I Won’t Let My Kids Watch That Very Special Christmas Episode

As the season gets jolly, time for a lesson in particularity

If modern Orthodoxy is supposed to be about reconciling Jewish tradition and the culture at large, I think I’m a pretty decent product of its community. I can recite Rambam but also Role Models, a film that has earned little love from critics, let alone rabbis. I often confound students at Yeshiva University with a short sermon or six on Anchorman, 30 Rock, or whatever recent obsession my wife and I happen to pursue on Netflix. And I’ve passed this Talmudic obsession with the minutiae of our entertainment on to my children, who spend more time than I care to admit basking in Bubble Guppies, The Octonauts, and myriad happy, shiny shows that give them as much pleasure as I get from laughing at (or is it with?) Liz Lemon.

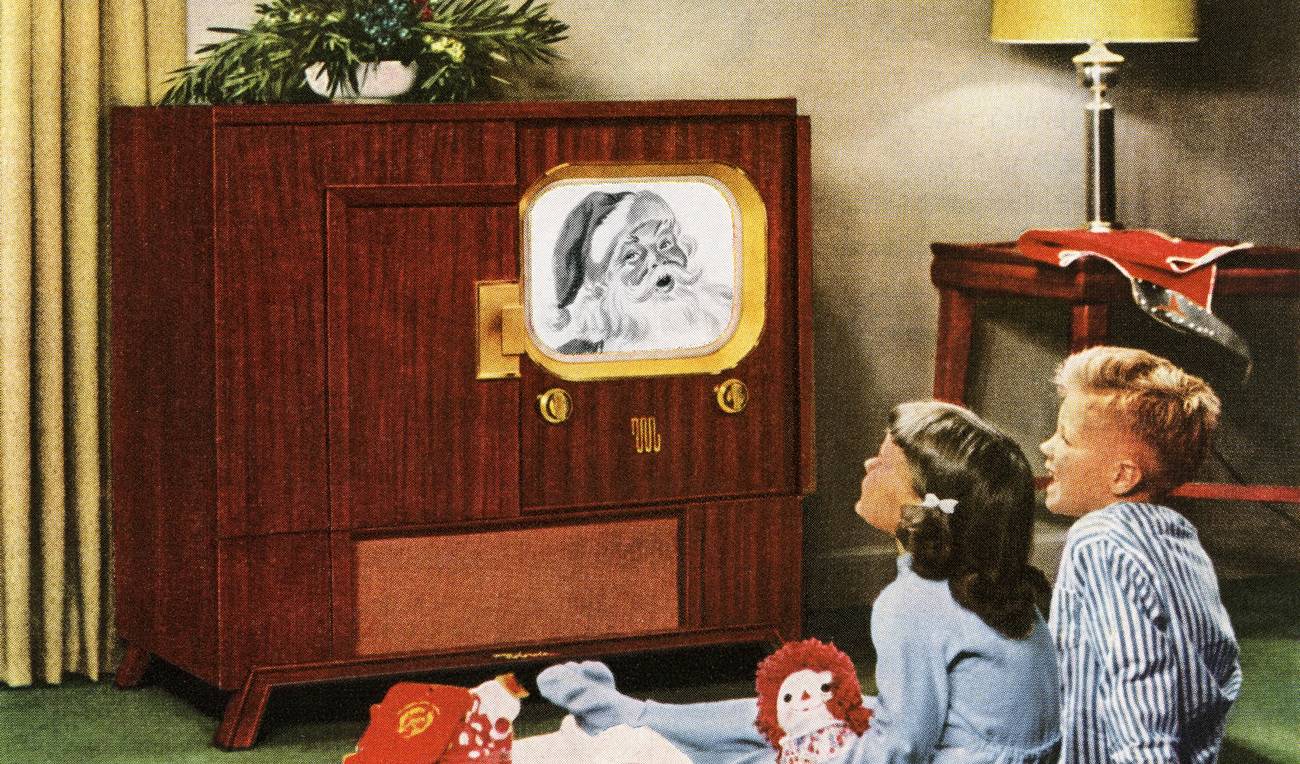

There’s only one exception to our devouring love of pop products: When their favorite shows present a Christmas episode, we insist that our children, as Liz would say, “shut it down.”

I understand that this may strike many as absolutely bananas. Am I afraid that some cartoon reindeer will inspire my precious Jewish children to run to the nearest church and forgo our local shul? Do I believe for one moment that Will Ferrell’s shiny green jacket and yellow pants in Elf will influence my 7-year-old to rip off his tzitzis and dress instead like he was straight outta the North Pole? Or am I some kind of Grinch whose heart, being two sizes too small, begrudges billions of Christians worldwide the validity and profundity and beauty of their belief?

The answer, thankfully, is none of the above. I don’t let my kids watch Christmas shows for a much simpler reason: It’s because I believe in diversity, and believe that differences matter and should be preserved, and believe that the best way to reach something approaching a universal worldview is to root it in the very specific details of my own particular tradition. And my tradition is Hanukkah, which I don’t want my kids to confuse with any other holiday.

In a culture dedicated to advocating openness—open minds, open hearts, open borders—this statement might strike you as, well, just a bit too closed off. Do we really need to be so jarring and so firm in our Jewish difference when the calendar offers an annual anchor in which such a wide swath of Americans, who are so diverse in all matters political, economic, and social, can put aside their distinctions and digital bloviating and find a sliver of communal commonality? After all, would it really be that hard to put up some red, layer on some white, pick up some shiny bulbs, and pick up a nonthreatening midsize shrub for the living room?

But that’s exactly the point. It wouldn’t be hard at all. Like so many of the opportunities America provides, it would be as simple as pressing the big red Staples button. It would be wonderfully uncomplicated to chow down on whatever I want in whatever restaurant I wanted. It would have been nice if the gentile girl next door was a dating option when I was growing up. It would be so gosh darn simple for my ears to bask in the audio glow of Mariah Carey singing to me about all it is that she wants for Christmas.

These facile pleasures have been the precise and constant challenges facing us American Jews. There has always been an unstated national presumption, sometimes even stated, that graduating from one’s backward-looking traditions and drinking from the goblet of cosmopolitanism makes one truly American. The pull of the cushioned rope of assimilation can beckon ever so convincingly. After all, one would be in the company of a Pulitzer Prize-winning Jewish author if you believed in “abhor[ing] homogeneity and insularity, exclusion and segregation, the redlining of neighborhoods, the erection of border walls and separation barriers” between Jews and their fellow countrymen. No less a towering figure than Eleanor Roosevelt, that matriarch of American morality, once lamented that “the difficulty is that the country is still full of immigrant Jews, very unlike ourselves. I don’t blame them for being as they are. I know what they’ve been through in other lands, and I’m glad they have freedom at last, and I hope they’ll have the chance, among us, to develop all there is in them. But it takes a little time for Americans to be made.”

If one’s entire framework of being is to be American, there’s no reason not to embrace all of this country’s aesthetic, cultural, and even spiritual offerings. Isn’t it icky and embarrassing to have to stick out as different, you might argue. Isn’t love love? Aren’t barriers bad?

These questions aren’t easy to answer. Nor, mind you, are they new: As early as Abraham, Jews were constantly asked to pick up and put themselves on the other end of the river, at an angle to the rest of mankind, fundamentally at odds with the culture. “To become a Jew has meant to be alienated from the rest of society,” wrote the 20th-century theologian Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik. “The destiny of Avraham Ha-Ivri, the lonely Abraham, has always accompanied the Jew … After all, the Almighty Himself is the Lonely One … Each individual should possess the strength to pitch his tent on one bank of the river while society lives on the other.”

Now, it hardly takes a rabbinic genius to realize that this statement presents its share of problems. If Jews are forever apart, can we ever become truly American? Or are we, like some of our most nefarious haters have often accused us of being, perpetual strangers who can never really fit in? Louis Brandeis addressed this question straight on. “A man,” he wrote, “is a better citizen of the United States for being also a loyal citizen of his state, and of his city; for being loyal to his family, and to his profession or trade; for being loyal to his college or lodge … [and] will likewise be a better man and a better American for doing so.” He was merely repurposing one of Judaism’s most ancient bits of insight for a modern age: Universalism is too vague an abstraction; you can only truly belong to a larger collective if you are first rooted in a specific tradition of your own. Put bluntly, it’s precisely apartness that makes our togetherness possible.

Which brings me back to my kids, and why they know to skip that bit where the Octonauts’ submarine reaches the North Pole during that “very special” holiday episode. The recently departed and sorely missed Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks taught us that pride in our unique traditions, to the exclusion of those of others, but not to their detriment—can be a lesson in “the dignity of difference.” That Hanukkah occurs in winter, that it happens in proximity to that other big holiday, gives us Jewish parents an opportunity to remind our children again of the beauty and necessity of our boundaries, of who we are and why we are this way, and of why we have no interest in picking up the traditions—even the holly, jolly ones—of our gentile friends and neighbors. By doing so, by delighting in Maccabees and latkes and dreidels rather than reveling in Dancer and Prancer and Rudolph, we do not shut ourselves in or lock ourselves out. Instead, we pridefully shine a light of our own, and remind others that this is what real diversity looks like: not a mishmosh of interchangeable ideas that all look and feel the same, but a mosaic of unique and distinct traditions coming together under one glorious tent. And if you feel like the only kid in town without a Christmas tree, here’s a list of people who are Jewish just like you and me.

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada, which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, Esther in America, Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth and Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.