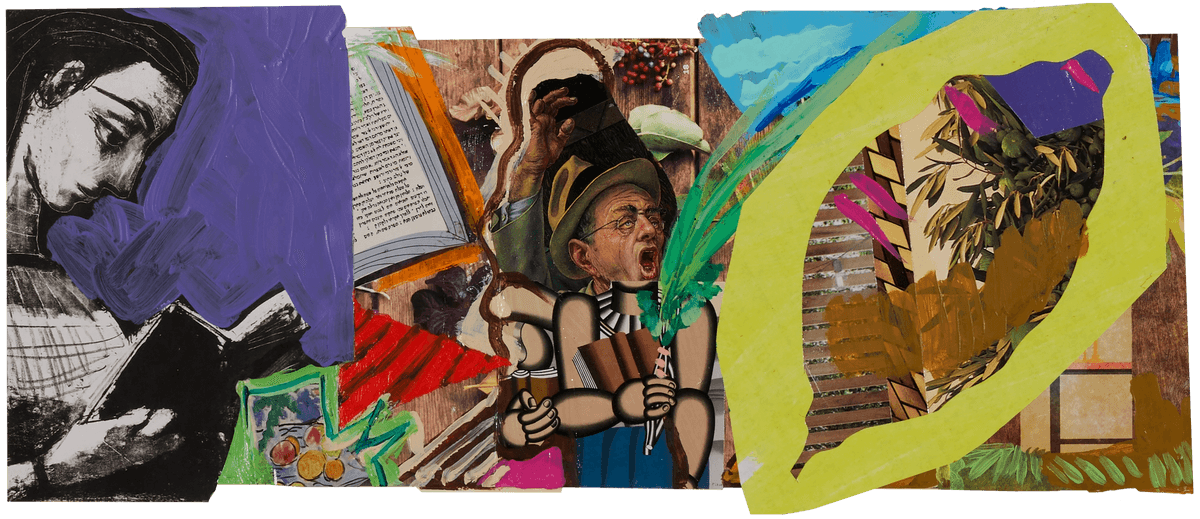

Sukkot

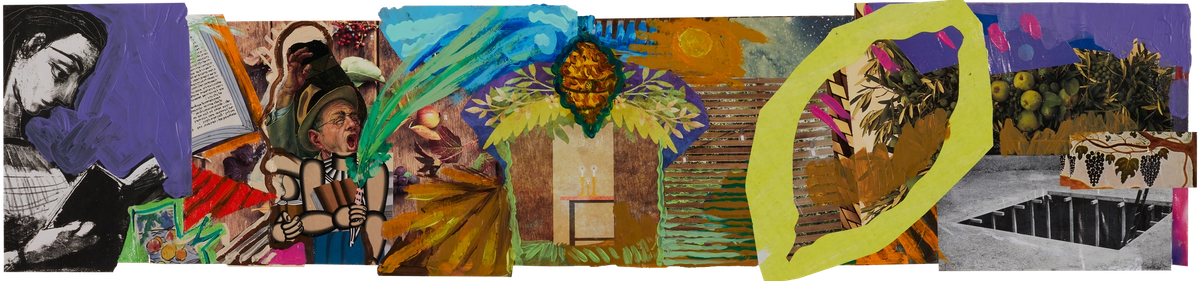

What is Sukkot? The year’s first harvest holiday, Sukkot celebrates the pilgrimage Jews made to the Temple in Jerusalem, bearing fruits and sacrifices. Traditionally, people build temporary dwellings—sukkahs—eating and sleeping in them during the holiday.

When is Sukkot? In 2023, Sukkot begins at sundown on Wednesday, October 16, and ends at sundown on Wednesday, October 23.

What’s it all about? Sukkot is without doubt the most action-packed of all Jewish holidays. We’re commanded to build a temporary dwelling, take our meals al fresco, shake special tree branches, and so on. This, in part, has to do with the fact that Sukkot (together with Shavuot and Passover) is one of shloshet ha’regalim, or the three festivals of pilgrimage, occasions on which the ancient Israelites traveled to Jerusalem and worshipped at the Temple. This means it’s both a religious and an agricultural celebration, calling for all manner of ritual.

The holiday, the Bible instructs us, is to be celebrated “at the end of the year when you gather in your labors out of the field,” after you’ve gathered your harvest “in from your threshing-floor and from your winepress.” Sukkot, then, is the time to survey—and give thanks for—the land’s bounty, a classic agricultural feast for a classic agricultural society.

But, Jews being Jews, the here-and-now of nature itself is nothing without history, and Leviticus makes it clear that the festival is also a time to commemorate the Israelites’ triumphant past: “You shall live in booths seven days,” it reads. “All citizens in Israel shall live in booths, in order that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt.” To hark back to our times of wandering, Jews are commanded to take all their meals in the sukkah, Hebrew for booth or hut.

This temporary reminder of our temporary dwelling in the desert, however, needn’t be just a solemn occasion to contemplate our historical hardships. Another key Sukkot tradition is welcoming ushpizin, or guests, into our sukkah. This custom, too, is not without its bit of religious significance: As the holiday lasts for seven days, we welcome in seven symbolic guests: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, Joseph, and David.

While the first two days of Sukkot are considered the holiday proper, the following five are referred to as Hol Hamoed, or the weekdays of the festival. During these days, none of the holiday’s religious restrictions apply, but Jews are forbidden from strenuous work and are commanded to use that time for enjoyment.

What do we eat? Unlike other holidays, there are no specific foods uniquely associated with the holiday. That said, because Sukkot celebrates the harvest, some people like to prepare seasonal vegetables and very often they decorate their sukkahs—in which it is a mitzvah to take meals—with gourds, strung popcorn, and other food stuffs.

Any dos and don’t? Perhaps the best known Sukkot custom involves the Four Species, or arba minim, as they’re known in Hebrew: a palm frond (lulav), myrtle tree boughs (hadass), willow tree branches (aravah), and a citron (etrog). Throughout the holiday, the four are held together daily and waved around daily along with an accompanying prayer, a commemoration of a similar ceremony practiced by the Temple’s priests in the ancient days.