Tisha B’Av

What is Tisha B’Av? It’s the day, the ninth of the Hebrew month of Av, on which a series of Jewish tragedies took place, notably the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE and the destruction of the Second Temple 656 years later, in 70 CE.

When is Tisha B’Av? Tisha B’Av 2024 begins at sundown on Monday, August 12, and ends at sundown on Tuesday, August 13.

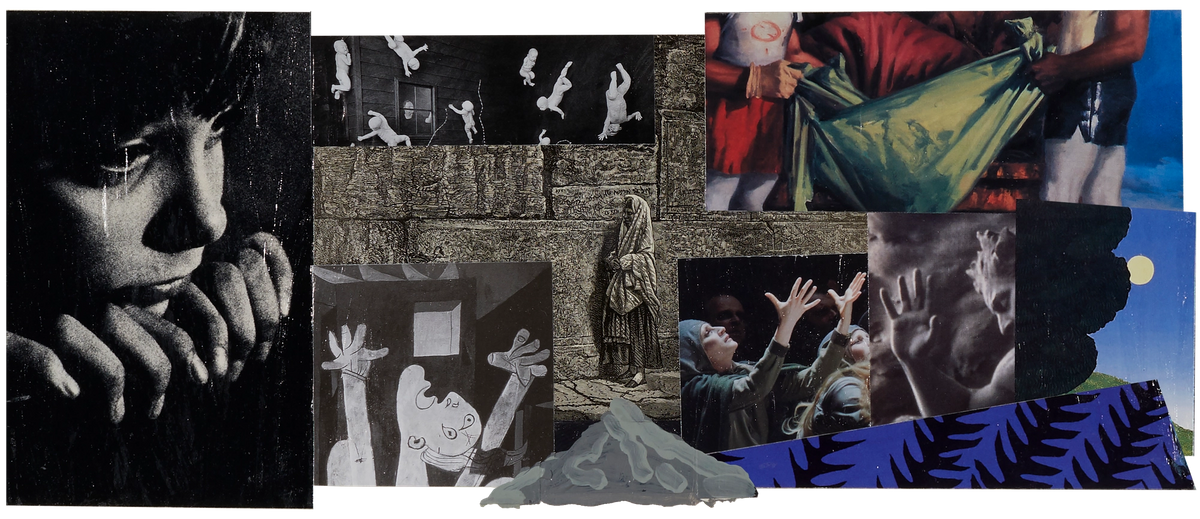

What’s it all about? We Jews should’ve known this day was no good when, on it, Moses’s spies came from the Promised Land with reports of a terrible place littered with walled fortresses and roamed by angry giants. Moses ordered his doubting emissaries killed, but the curse of Tisha B’Av lived on: the First Temple was destroyed on this day in 586 BCE. The Second Temple suffered the same fate exactly 656 years later, in 70 CE. Sixty-five years after that, in 135 CE, the Bar Kokhba revolt failed, its leader was killed, and its flagship city, Betar, was destroyed. Then, one year later, Jerusalem itself was burned, the Temple area plowed, and the fate of the Jews sealed for millennia. As if further insult was needed, in 1492, King Ferdinand of Spain signed the Alhambra Decree, setting Tisha B’Av as the deadline for all of Spain’s Jews to leave for good.

Coming at the end of the Three Weeks of mourning, which began with the 17th of Tammuz, Tisha B’Av signifies the conclusion of the period known as Bein Hameitzarim, a time of reflection and abstinence from pleasure.

What do we eat? Nothing. But unlike Yom Kippur, most rabbis tend to be a bit more lenient about fasting, making exceptions not only for those whose lives are seriously at risk but also for the ill and the generally unwell.

Any dos and don’ts? Don’ts, mainly. Anything that gives us pleasure is prohibited, which rules out, among other things, bathing, wearing leather shoes, and carnal pursuits. If you thought maybe you’d replace the day’s heavy petting with Torah study—think again. Reading our Book of Books is considered a supreme joy and is therefore forbidden on Tisha B’Av. So is laying tefillin, as phylacteries are referred to as pe’er, or glory, and this is a decidedly inglorious day for the Jews.

Anything good to read? We’re compensated for the day’s prohibitions with two splendid literary masterpieces: the Book of Eicha (Lamentations), which is read in the evening, and the Kinnot, poems of lamentation, in the morning. Taken together, these two are a powerful lesson in mourning. Eicha, while lyrically describing the ruin of Jerusalem, also speaks of a hopeful future, a time when the children of God, chastised, will learn their lessons and return to their former glory. The Kinnot, a vast and changing collection of works written through the centuries, strikes very much the same tone. The most famous author to work in the form was Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, who forever changed the genre’s focus from weeping over the tragedies of the past to looking expectantly at a brighter future. Be sad, these texts tell us, but not for long.