Yom Kippur

What is Yom Kippur? Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is when Jews fast and ask forgiveness for the sins they committed in the past year and for ones they’ll inadvertently commit in the new year to come.

When is Yom Kippur? In 2024, Yom Kippur begins at sundown on Friday, October 11, ending at sundown on Saturday, October 12.

What’s it all about? Yom Kippur is the most awesome of all Jewish holidays. We mean that literally: The very last of the Days of Awe, the 10-day period beginning with Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur marks the sealing of the Book of Life and with it our fates for the coming year. Jews—even some who cheerfully ignore other holidays—fast, repent, confess, and do their best to unload themselves of their sins and get on the Almighty’s merciful side. Yom Kippur occurs on the 10th day of the seventh month.

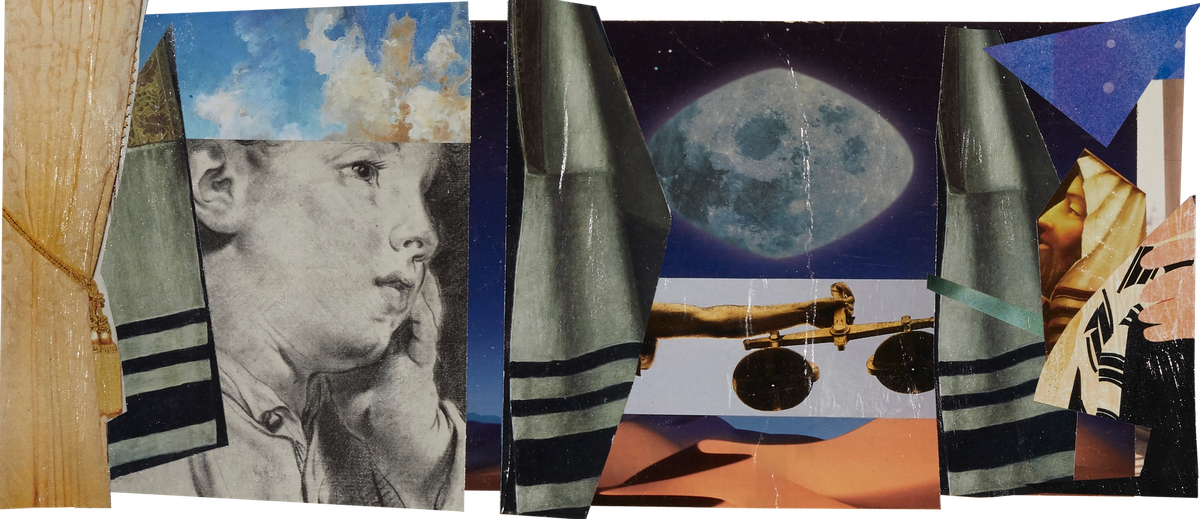

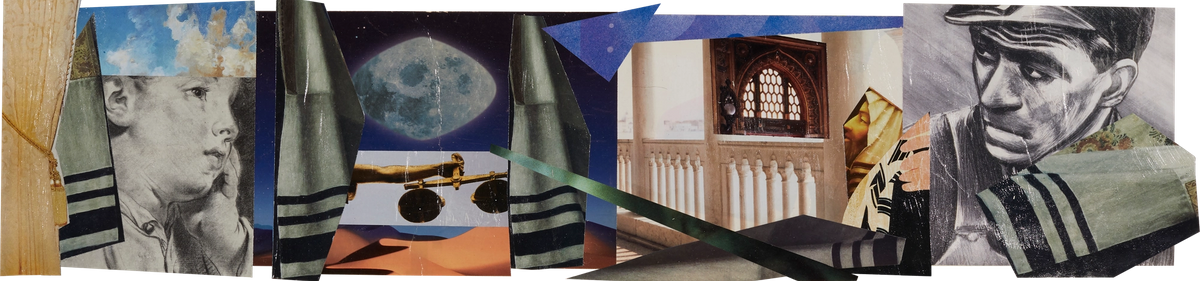

Any dos and don’ts? The Mishnah, in tractate Yoma 8:1, is very clear on the don’ts: no eating or drinking. No wearing leather shoes. No bathing. No anointing oneself with perfumes or lotions. And no sex. The Bible itself, interestingly, mentions nothing about these prohibitions. Leviticus 23 only forbids us from doing work and tells us to afflict our souls, not our bodies. After the destruction of the Temple, the exile from Zion, and the writing of the Talmud, the holiday’s focus shifted from the High Priest and his purification rituals to the responsibility of each and every Jew to atone for his or her own sins. And while the connection between a gurgling stomach and a reflective mind may be lost on some, it is worth noticing that Yom Kippur is the only fast day on the Jewish calendar that is not observed in commemoration of some historical tragedy, but rather designed purely to allow us to take leave of earthly distractions and focus on our sinful souls. On the do side, it’s customary to wear white to symbolize one’s purity. To the same end, many Orthodox men dip in the mikveh the day before Yom Kippur for extra cleansing, which is probably not a bad idea given the prohibition on baths.

The holiday’s liturgical highlight is perhaps the most fascinating, controversial, and thrilling of all Jewish prayers, the Kol Nidre, which is recited to usher in Yom Kippur. Aramaic for “all vows,” Kol Nidre releases those who recite it from all of the vows they will make from the current Yom Kippur service until the same service in the next year. (This, by the way, wasn’t always the case: It was Rashi’s son-in-law, Rabbi Meir Ben Samuel, who changed the prayer from the past to the future tense, wishing to stress that its potency was not in retroactively releasing us from our past vows, but rather from future ones, a much more powerful proposition.) It, too, has its beginnings in ancient Israel, where the making of vows was so much the trend that the Torah made a point of warning people against making God a promise they couldn’t keep: “When thou shalt vow a vow unto the Lord thy God,” says Deuteronomy 23, “thou shalt not be slack to pay it; for the Lord thy God will surely require it of thee.” What, however, of those who made a vow and couldn’t keep it? They required a special rite of absolution freeing them from their word. Such a vow—called hattarat nedarim, or the undoing of vows—finally came into being. The other major prayer is the Ne’ilah. Hebrew for locking, it is recited at the end of Yom Kippur and concludes with a long blowing of the shofar. With this, tradition has it, the Gates of Heaven are locked, our opportunity to atone over, and our fate determined.