A Brighter Future

There’s a new wave of North Americans moving to Israel for a different way of life—and they’re not who you’d imagine

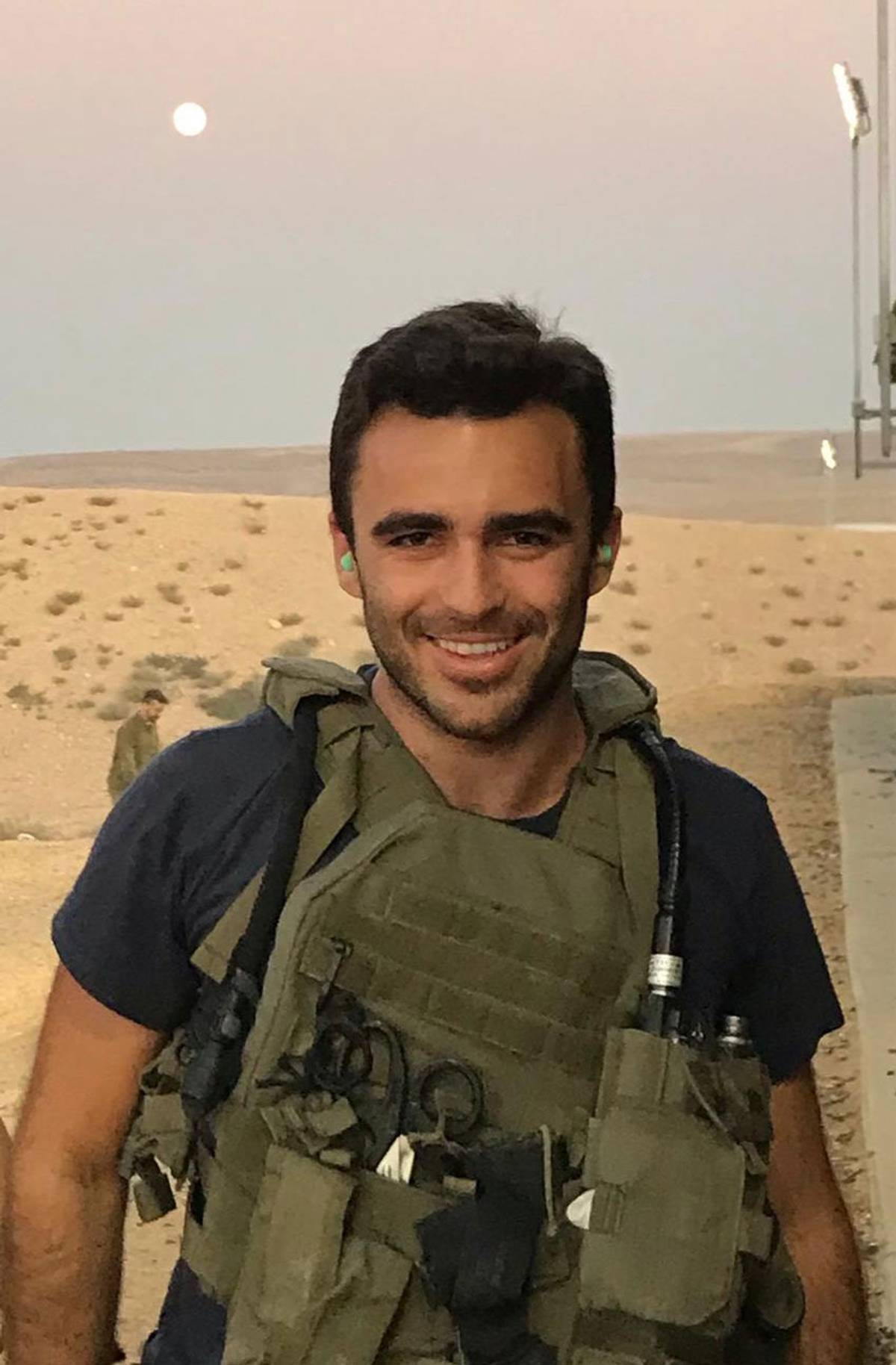

Sam Meyer had no idea what he was getting into when he headed to Israel in 2011 after high school to enlist in the IDF. His plan had been pretty basic for a nice Jewish boy from Toronto—do a stint in Machal, a 14-month program for Jewish youth who live overseas, then return home, go to college, and become a lawyer.

But things went sideways fast. First, he made it through a savage selection process for the legendary Israeli Air Force Unit 669, which whittled 10,000 candidates down to 30 warriors. The special unit was created after the Yom Kippur War to rescue pilots downed behind enemy lines—the equivalent of the superelite pararescue units known as PJs in the U.S. Air Force, with a similar reputation for being badass special operators. Meyer was trained not only to fight his way into and out of the worst situations, but also to save lives as a combat medic. During his three-and-a-half years of service, he was regularly called on to rescue the grievously wounded or endangered, sometimes fighting through 10-foot ocean waves or rappelling into a crater to reach a soldier who had fallen down a mountainside, not to mention the regular demands of mounting complex exfiltrations of soldiers under fire.

While in the unit, Meyer decided he wanted to become a doctor, and less than two weeks after his discharge, he was in New York City at Columbia University studying for his undergraduate degree on an accelerated schedule. As a student, he still served three weeks of active reserve duty per year and also took it upon himself to create and train (with the help of a group of 669 alumni) an EMT team on the island of Jamaica, the first ever to serve local residents. He then earned a master’s degree in global health policy at the London School of Economics. In the summer of 2020, he started medical school at Tel Aviv University with the hope of serving as a doctor in Unit 669, or possibly one day running a hospital trauma department. A couple months later, he was tapped as a consultant for Israel’s Ministry of Health to work on COVID-19 testing and contact tracing.

Meyer’s story, though in many ways exceptional, is also representative of a new wave of immigrants to Israel who are going not out of personal fear, nor only to protect an embattled homeland, but because they see Israel (and IDF service) as a way to improve and expand their lives. Many of these new olim do not fit the earlier picture of vulnerable Jews from countries like France or the former Soviet Union, fleeing imminent threats or declining fortunes at home. Nor are they primarily motivated by religious belief. Like Meyer, they’re moving to Israel because they believe it can offer a unique place to unlock their human potential and create a robust future in a vital and growing society.

In fact, COVID-19 unleashed an unprecedented jump in interest in aliyah from all ages around the world. In July, Jewish Agency Chairman Isaac Herzog announced that he expected a startling 250,000 immigrants over the next five years, 15,000 more per year than pre-pandemic numbers—a 42% increase. But what surprised the Jewish Agency even more was the unexpected jump in calls requesting information about aliyah from residents of Western countries in particular, up 31%. The next step in the immigration process, actually opening a file with the Jewish Agency, saw a 91% increase from Western countries, and a 400% increase from North America, mainly driven by interest from residents of New York, New Jersey, California, Florida, and Ontario.

COVID-19 unleashed an unprecedented jump in interest in aliyah from all ages around the world. In July, the Jewish Agency announced that it expects 250,000 immigrants over the next five years.

Since the 1948 War of Independence, Jewish youth have packed their bags and flown to Israel to volunteer for the IDF when the country was threatened. In recent years, though young American Jews have shown the same impulse, actual moves tend to be executed after a year or so delay—giving time for those highly scheduled and closely parented to convince their families of the depth of their convictions, or to complete the schooling they may require for parental approval. And some Gen Zers take the same view that Meyer did, considering the chance to serve in the IDF not only as an honorable duty, but also as a means to personal growth. Shira Wald, a 22-year-old graduate of the University of Massachusetts who grew up in a “more traditional modern Orthodox” home in Newton, Massachusetts, made aliyah in 2020, and enlisted in the IDF in January 2021. “People who go into the army come out mentally stronger and more independent, and I hope that I will gain that,” she told Tablet.

Yael Katsman, vice president for public relations at Nefesh b’Nefesh, which facilitates aliyah from the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, said in an interview that the “anecdotal correlation” between aliyah interest and moments when Israel is in distress has historically occurred when “Jews who feel emotionally connected to Israel can no longer continue being so far from the country they love when it is under attack.” Today, that emotional connection no longer requires the threat of war for its consummation: The massive disruptions caused by the pandemic are providing a new freedom. Katsman said people tell her they are finally doing what they always knew they wanted to do. “Basically COVID has readjusted people’s priorities and plans—and working remotely and keeping up with family via Zoom has shifted their ideas of where they need to live.”

According to Nefesh b’Nefesh, before COVID-19, applications for aliyah among non-Haredi Jews aged 18-34 had risen at an average of 10% year over year between 2005 and 2016, with a notably large increase (77%) during the Gaza War of 2008-2009—a trend the Jewish Agency expects to explode upward as Western economies deal with pandemic fallout and political disruption. With many American university campuses closed to in-person learning, but still dominated by political movements that are sometimes openly hostile to Jews and suspicious of what they see as outdated or racist educational norms, some young Jews are looking to Israel as a welcome option. (During the first three years of Donald Trump’s presidency, the number of young people expressing interest in making aliyah dropped slightly, though it’s unclear what if any correlation exists.)

The new kind of olim who began to arrive from the West in the past decade are motivated not only by a desire to defend the country, but also because they believe Israel will offer them a better life. Marc Rosenberg, vice president of diaspora partnerships for Nefesh b’Nefesh, sees two separate phenomena operating together. First, Israel, at nearly 73, is now a mature country with international standing. “The grown-up Israel is becoming a real option for people,” he told Tablet. “It’s not the tzedakah country, it’s not the fantasy of the 1960s. It’s not just a gap-year country. Rather, Israel is a thriving place with a hot technology sector, many American companies, and a good quality of life. Young people are looking at the numbers and asking themselves, is it possible and is it a good choice?”

Mikey Weiss made aliyah in 2016 after graduating from Johns Hopkins University, and served in the elite Palsar Nahal, the special forces reconnaissance unit of the Nahal Infantry Brigade. He now serves as strategic finance manager for a startup and said a quick look at the contact list in his phone pulls up the names of at least 50 Americans his age working and living in Tel Aviv. One of them, Jessica Borenstein, 29, said she moved to Israel not for ideological reasons—her husband had those—but only after determining it would be a good career move.

“Back in the States I was working as a management consultant, and when I came here I pivoted to tech,” she told Tablet in an email. “I now work in business operations at a financial technology company. I definitely think that moving to Israel for work is a viable alternative, depending on what industry you’re in. If you work in tech or venture capital it’s an attractive, competitive alternative and a lot of people make the move.”

She added that calculations must be made. “Generally you are aware that you will make less money, but it’s not always as big a difference as you would think.” On the plus side, there are “valuable lifestyle aspects of living in Tel Aviv—culture, beach, weather, and proximity to Europe.”

Michael Harris, 27, a New Yorker who made aliyah in 2016 and now works in Tel Aviv at the U.S. consulting firm Ernst & Young, said that “If you walked around the boardwalk in Tel Aviv, and it was your first time in Israel, you might think that English was the official language of the country. There is definitely a thriving community of Americans living in Israel, both coming here to serve in the army and go to college. And there are also a lot coming after college to live their lives here and set up a full professional and social life for themselves in Tel Aviv.”

The “normalization of Israel,” which will likely accelerate as the result of recently inked agreements with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco, is not the only factor in increased interest from American Jews. Rosenberg of Nefesh b’Nefesh said COVID-19 has provoked an additional phenomenon, as ethereal as it is profound: “People are asking themselves, ‘what can I not live without?’”

A friend in her early 50s surprised me a few months ago by telling me she was moving to Israel by herself. I knew she loved the country, and had been working on her Hebrew, but why now? “My boss could no longer tell me I can’t work remotely, because everyone is working remotely,” she told me. “And after last year’s Zoom Pesach, I realized I could stay in touch with my family. So I was no longer willing to keep putting off what I really wanted to do.” (She prefers to remain nameless because she hasn’t yet told her boss the move is permanent.) Even during Israel’s second COVID lockdown, I received an optimistic text from her: “It feels so great to be here!”

Like the Shakespeare saw about libations, the pandemic has provoked the desire but reduced the performance, at least temporarily. Although the virus led unprecedented numbers of North American Jews to try to make the move to Israel, many of the El Al planes scheduled to take them there were grounded. Even IDF call-ups were canceled or postponed. After Shira Wald made aliyah, she flew home to await her IDF induction, which was scheduled for March 2020. But her IDF date was canceled, as were two of her El Al flights. She persevered and found a program, Maslul Nitzan, which helps people like her navigate the Israeli bureaucracy, places young immigrants in kibbutzim during their time as lone soldiers, provides ulpan, and otherwise guides them through the process. She was accepted, and has now finished basic training in the IDF. She is learning to be a commander of the Field Intelligence System Technician course. She said that a couple inductees from Europe who planned to be in her Maslul Nitzan group were held back by bureaucratic delays caused by the pandemic.

On March 18, 2020, to control the spread of the virus, Israel prohibited entry into the country of anyone who was not an Israeli citizen or permanent resident. Dafna Laskin, director of engagement for Young Judea, which runs its immersive Year Course in Israel, said that to get around the restrictions, special permits were granted to participants in MASA-sponsored and other yeshiva or seminary programs certified by the government. Additional obstacles include “closed consulates and embassies, increased paperwork processing times, canceled flights, and fear of traveling,” she told Tablet. However, she found workarounds. “We were able to get 30 passport renewals here in the United States expedited at a time when expedited services have not been available, but it took a lot of behind the scenes finagling.”

With similar creativity and determination, Nefesh b’Nefesh said it was able to arrange 41 El Al charters for olim, managing to help 3,168 Jews from North America make the move in 2020—only a small percentage of the 14,022 who wanted to do so, itself an increase of 206% from 2019. The Jewish Agency expects the backlog of people who wanted to move but could not be accommodated will be absorbed in 2021-2022. New communications technology actually allowed Nefesh b’Nefesh in 2020 to expand its contact with Jews wanting to make aliyah—hosting 113 online aliyah informational events, a 318% increase from 2019, with a total of 15,277 participants (compared with 1,953 in 2019, a 682% increase).

And although commercial El Al flights were grounded for much of the year since March 2020, the airline is now reintroducing limited flights to the United States, while United, Delta, and other American airlines have continued to fly into and out of Israel. Laskin said, “United particularly has been flying once a day roundtrip Newark-Tel Aviv since this all started. From what I hear, the flights from New York to Israel have been full.”

If all roads lead to Jerusalem, a young person’s chances of enjoying a soft landing are improved by prior attendance in a long-term program in country. With American colleges closed to in-person learning, it’s no surprise that gap-year programs have seen jumps in enrollment. Young Judea’s Year Course, which usually sends 100 students from North America and England to Israel, sent 211 in 2020, and had a long waiting list. Laskin said COVID-19 offered an unexpected opportunity for students, many of whom told her, “I got into my dream school, but it’s not going to look like the way I expected it, so this is my chance to do something I’ve always wanted to do.” Ofer Gutman, acting CEO of MASA Journey, told Tablet that applications were up 15% from 2019. (Young Judea’s numbers are counted as part of MASA’s.)

Programs that improve young people’s Hebrew skills lead to other opportunities. Young Judea’s Laskin said that in 2019, out of 100 Year Course participants, four or five enlisted in the IDF, and the same number enrolled in college in Israel. After making aliyah and serving in the IDF, olim receive generous educational benefits that generally cover tuition for undergraduate education or a master’s degree at the large Israeli universities: Hebrew University, TAU, Technion, Ben-Gurion, and Haifa University. Excellent Hebrew skills aid a candidate’s chance of acceptance. Partial tuition help is also offered at the michlalot, the private colleges, like IDC Herzliya, which conducts classes in English and offers undergraduate and graduate degree programs. With tuition for private American universities reaching $75,000 per year, and the quality of that education perhaps in question under the influence of “woke” culture, Israeli schools represent not only a dramatically more affordable option, but possibly an academically superior choice.

Of course, life in a new country isn’t always easy for recent arrivals. The young people I spoke with all made special efforts to bring their Hebrew skills up to par. Hannah Cook, 23, studied the language diligently at Brandeis University and made sure to live with native Israelis upon moving to Tel Aviv. Leora Mietkiewicz, 27, a Canadian who made aliyah in 2019, hangs out as much as she can in the Mahane Yehuda neighborhood and got a side job near the shuk so she could refine her language skills. Life as a lone soldier can be difficult even though programs like Garin Tzabar and Maslul Nitzan make every effort to act as substitute family. Weiss, the startup manager, wanted to get into one of the IDF’s most elite reconnaissance units, Sayeret Matkal, which is nearly impossible even for native Israelis. Serendipity led him to an introduction at a wedding with a veteran of the unit, and the man became his adopted father in Israel, advising him through every twist and turn. Though Weiss didn’t make that unit, he earned a friend and mentor for life.

I definitely think that moving to Israel for work is a viable alternative, depending on what industry you’re in. If you work in tech or venture capital it’s an attractive, competitive alternative and a lot of people make the move.

And sometimes, that which makes Israel meaningful also sends people back home. Ben Kravis attended college at Tulane and made aliyah in 2016. He served as a staff sergeant in the paratroopers, then had to decide whether or not to go back to the United States to attend medical school, where he had already been accepted. Kravis was born in Japan; his mother is Japanese and converted to Judaism before getting married. His parents now live in the United States. Kravis said: “During my time in the army, I really realized how important family is in Israel and I internalized that, and so I realized I would feel bad for my family if I stayed there. I see how much my mom misses Japan and her family—I would feel bad doing to her and my dad what she did—because she misses her family so much.” Kravis is now in medical school at Tulane University but ponders one day returning to Israel. He even envisions where he would live: in the north.

For Cook, what pulled her to move was a longing so powerful that it dominated her thoughts and her plans every moment since 2013, when she was 15 years old and visited Israel for the first time with her summer camp. “Literally as soon as we landed at Ben-Gurion Airport I felt I was totally at home.” The day she returned to America, she began Googling ways of getting back. She discovered a brand-new Israeli high school, which—following a chance meeting with an Israeli student at her family shul who knew the school’s founder—she decided to attend for her junior and senior years. “He gave a lecture titled, ‘From the IDF to the DCH’ [Dartmouth College Hillel], and he turned out to be one of the people who most shaped my life.” She returned to the United States after graduating and attended Brandeis, then had an internship back in Israel before making aliyah in January 2020. She found a job doing exactly what she wanted, “connecting Israelis and Americans because I feel best in the space between the two.” She said most of her friends are native-born Israelis. “It’s a love story.”

Mietkiewicz first visited Israel when she was 16. “The whole time I was there,” she said, “I had these thoughts, ‘Leora, you need to be in Israel.’ I felt I could not leave.” She did go back to the United States, but returned to Israel with her father for Passover soon after, and “since then, I always needed to know when I would be back next in Israel. I was fine being in Toronto as long as I knew when I would be back.” She attended college at McGill and now works for Camp Ramah in Israel, the same program that brought her to Israel the first time. An only child, she is acutely aware of the significance of her decision for her family. But she was born into a world of social media, and she has found a way to meld her real life and her virtual existence into one seamless whole. “I really love cooking and baking and going to restaurants. My favorite place is Mahane Yehuda, and I share those activities online on Instagram. If I eat lunch in a nature reserve, I’ll post it.” With some FaceTime calls now and again, “I’m completely up to date with my family and friends.” She hopes her parents will follow her one day. Her mom lived on a kibbutz in 1973 and made aliyah, but later moved back to Canada. “Once my dad retires, I think he’ll come. And my mom did it once, so she’ll do it again.”

Harris, the consultant in Tel Aviv, said he knew at 17 he was going to make aliyah. “Moving to Israel and serving in the army was just a question of when, not if.” Studying politics as an undergrad and international relations as a graduate student at New York University only solidified his determination. He enlisted at 23 and served as a basic combat training commander for recruits to the Armored Corps. “Everything hits you very quickly in basic training, whether it’s the intense moments, the difficult or funny moments—there is something very special about that time—not that it’s always fun, but it’s definitely unique. I experienced that as a soldier and wanted to help others with it.”

He has internalized the Israeli Army’s credo, and is now gratified to play it out in his own life. Working with government bodies on the forefront of the pandemic, Harris is particularly aware of the hardship COVID has wreaked on Israeli society, including unprecedented strains on public health, governance, education, and employment. “As much as I possibly can, I try to put myself in situations where I’m contributing to something that is greater than myself—whether it’s the army or my job where I work with government clients to help them with the unique challenges they face.”

Bottom line, he said: “I believe this is one of the most exciting and pivotal moments in Jewish history, it’s one historians will write about 500 years from now, 1,000 years from now. For me as an American Jew, watching all this from the sidelines and not being part of this incredible project was unfathomable. I wanted to be a part of the story.”

Emily Benedek has written for Rolling Stone, The New York Times, Newsweek, The Washington Post, and Mosaic, among other publications. She is the author of five books.