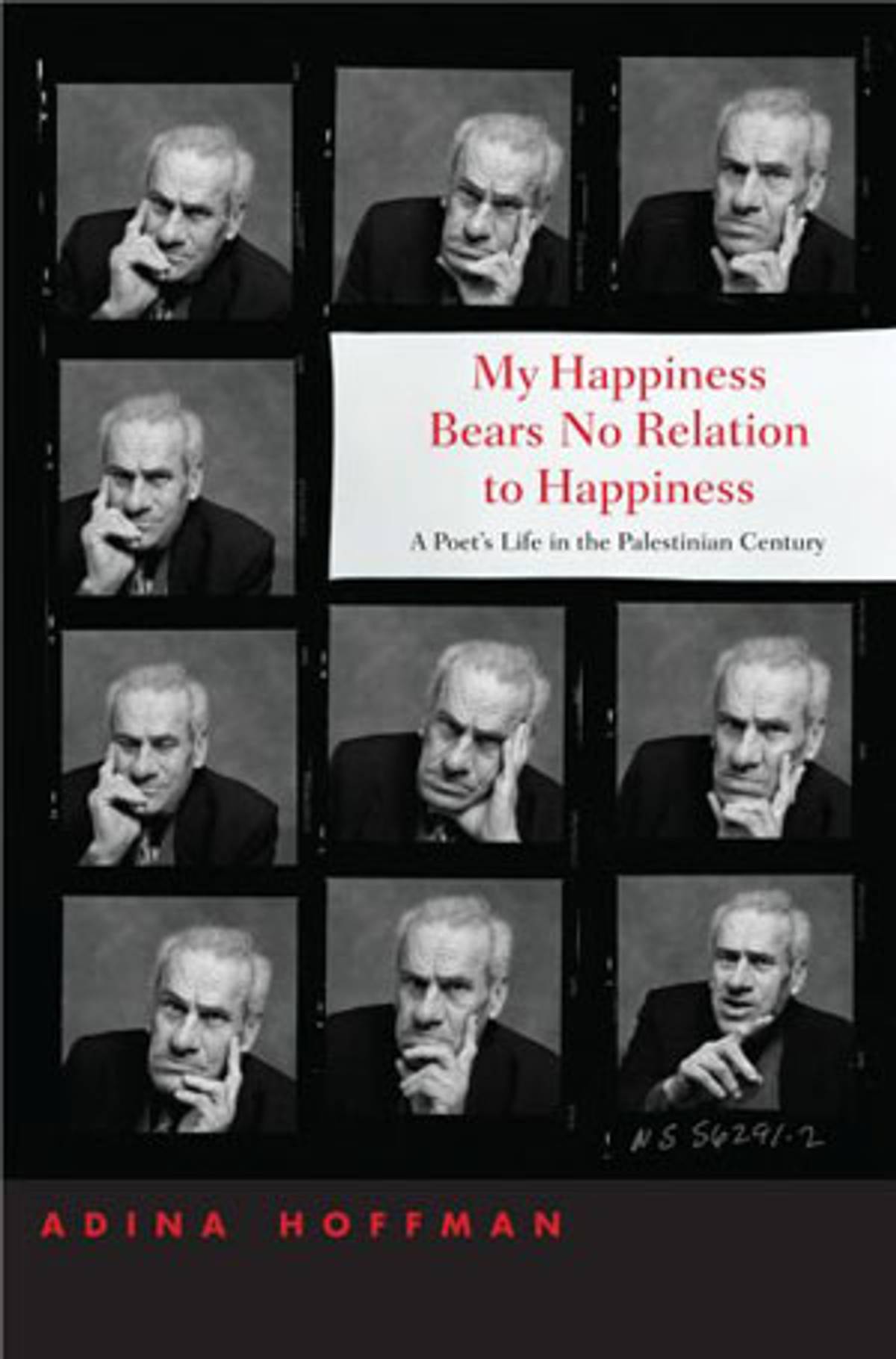

If you go looking for My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness: A Poet’s Life in the Palestinian Century in the bookstore, you will probably find it in the biography section; but it is an unusual sort of biography that neglects to the put the name of its subject in the title. Few readers will recognize the blunt-featured man who looks out from the cover of the book as Taha Muhammad Ali, the Palestinian poet whose life and work are Adina Hoffman’s ostensible subject. But then, not many more readers would recognize his name, either. As Hoffman acknowledges, he is not as well known, even among Palestinians, as a poet like Mahmoud Darwish, whose death last year was mourned across the Arab world.

Taha Muhammad Ali was born in 1931, and while he has been part of the Palestinian literary scene for most of his life, he did not publish his first book of poems until 1983. Over the last few years, however, he has won a growing international readership for his humane, melancholy, sometimes comic poetry, thanks in large part to the efforts of Hoffman, a film critic and author of the essay collection House of Windows, and her husband, the poet and translator Peter Cole. Hoffman and Cole, American-born Jews who live in Jerusalem, are two of the founders of Ibis Editions, a remarkable small press that publishes Hebrew and Arabic literature in translation. It was Ibis that brought out the first English edition of Muhammad Ali’s work, Never Mind, in September 2000—“in the same month,” Hoffman notes, “that the al-Aqsa intifada broke out.”

That kind of grim calendaring can be found in every chapter of My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness. “In 1946 Taha read his first modern book,” Hoffman writes—just around the time the Irgun blew up the King David Hotel. He produced most of the poems for his first book in 1982 and 1983, during the months when the IDF was invading Lebanon, leading to the massacres at Sabra and Shatila. The most important date of all in Muhammad Ali’s story, however, is July 15, 1948. It was on that night that the Galilean village of Saffuriyya, where Muhammad Ali was born and raised, was captured by the army of the newborn Jewish state.

Along with most of the village’s population, the teenage Muhammad Ali and his family fled on foot, ending up in a refugee camp in Lebanon, where his 12-year-old sister, Ghazaleh, died of meningitis. (Six other siblings had died in infancy, Hoffman writes, and the poet was actually the fourth boy to bear the name Taha.) They were able to sneak back into Israel the following year, and eventually even to gain Israeli residence cards, but they were never to return to their ancestral village; Saffuriyya had been leveled and turned into Tzippori, a moshav. Instead, the future poet settled in Nazareth, where he opened a small grocery store. Eventually this grew into a prosperous souvenir shop catering to Christian tourists, which Muhammad Ali still owns today. (The book includes several photos of this eccentric-looking establishment, which is decorated with a sign bearing a quotation from Keats: A thing of beauty is a joy forever.”)

Even this dry summary of Muhammad Ali’s story shows why it is such a painful one for a Jewish reader to encounter, and why Hoffman writes it with such missionary fervor. Here is a man whose life was grievously damaged by the Jewish state—who was expelled from his land, separated from his family, and subjected to discrimination and violence. Hoffman makes clear that Muhammad Ali has never wanted to be a “committed,” political poet—neither his innovative free-verse style nor his ironic humor are suitable for the kind of platform oratory that move large crowds. Yet inevitably, in speaking in his own voice of his own experience, Muhammad Ali is voicing the suffering of his Palestinian generation.

In his poem “The Fourth Qasida,” Muhammad Ali addresses Amira, the girl to whom he was betrothed in childhood, but whom he didn’t get to marry because she wound up on the wrong side of the Lebanese-Israeli border. In the process, he turns Amira into what Hoffman calls an archetypically literary stand-in for all of Saffuriyya and indeed for all that is ever lost to time, to death, and to separation”:

When our loved ones leave,

Amira,

as you left,

an endless migration in us begins

and a certain sense takes hold in us

that all of what is finest

in and around us,

except for the sadness,

is going away—

departing, not to return.

The fact that Taha Muhammad Ali is a gifted poet and a very appealing personality—Hoffman writes of his ability to charm Arab, Jewish, and American audiences alike—makes him easy for the reader to care about. But it does not make his fate inherently more significant than those of hundreds of thousands of other Palestinians who suffered the same injuries. Here, in fact, lies the main trouble with Hoffman’s book: she is writing about one man, but she is really interested in what she calls, with polemical exaggeration, “the Palestinian century.”

Thus she devotes much of the first half of the book to recounting the Jewish-Arab clashes of the 1930s and 1940s, culminating in Israel’s War of Independence. By focusing on Saffuriyya and its people, Hoffman makes the human costs of this conflict come to life, and she clearly means to confront American and Jewish readers with the facts of Palestinian suffering. But this Saffuriya-centric approach also allows Hoffman to neglect the larger history of the war and the period, and to portray Israel as the aggressor in what was in fact a war in defense of its very existence. Her retrospective indignation is not the best lens through which to view this complex history.

The more original and valuable parts of My Happiness deal with Palestinian literary culture. Hoffman shows how Palestinian writers dealt with obstacles from every side—they were cut off from foreign books and magazines by the Arab boycott, and subjected to censorship by the Israeli government—and how they evolved new institutions and forms in response. The poetry festivals of the 1950s and 1960s brought poets face to face with their audiences, thus making “poetry the most important means of political expression for the hemmed-in, cut-off Palestinian citizens of Israel.” The publications of the Israeli Communist Party, the only one to welcome Jews and Arabs equally, were another important venue for Palestinian writers. Hoffman shows how, despite these meager resources, poetry became central to Palestinian culture in a way that poets in America can hardly imagine.

It is a problem for Hoffman’s book, however, that Taha Muhammad Ali played little role in this story. An autodidact with just a few years of formal schooling, he spent many years teaching himself to write classical Arabic and exposing himself to modern literature from around the world. While his shop in Nazareth became known as a kind of open-door salon, and he befriended many Palestinian writers, he seems to have been shy about writing or publishing until he was in late middle age. When he read his work at a London festival of Arabic literature, in the late 1980s, another writer exclaimed, “How is it that we didn’t even know you existed?”

And while Hoffman knows the poet well—she refers to him as “Taha” throughout—and has conducted years of interviews with him and his acquaintances, he remains a rather abstract and guarded presence throughout My Happiness. Hoffman warns the reader of the poet’s tendency to embellish his stories—his formidable storytelling gifts tend to involve fanciful improvisation on more-or-less true themes”—but she is constrained by the political barriers and cultural differences between them from challenging Muhammad Ali’s self-presentation.

Indeed, she is clearly uncomfortable speaking critically about any aspect of Palestinian life. She writes sentimentally about the relationship between Taha and Amira, for instance, when it would make more sense for her, as a secular liberal, to question the sexist archaism of promising a girl to a husband at birth. But then Hoffman is not trying to be impartial, and she is not really writing a biography. She is, rather, confronting the almost unbearably difficult history that binds and divides Jews and Arabs in Israel; and she does this with a courage that the reader can only hope to emulate.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.