The Aboriginal Rights of the Jewish People

Do the Jewish people have legal ‘rights of entry, sojourn, and settlement’ to the land of Israel?

U.N. Security Council Resolution 2334 (2016) claims “establishment by Israel of settlements in the Palestinian territory occupied since 1967, including East Jerusalem, has no legal validity and constitutes a flagrant violation under international law.” This dictat is legally defective for several reasons, but my focus here is restricted to the Jewish People’s aboriginal rights of entry, sojourn, and settlement.

Aboriginal rights pertain to a culturally complex, sociological “People” born via general self-identification under a specific name. Thus, peoplehood is flexible enough to embrace the specifically “American” People, which is of mixed ancestry, but also the virtually homogeneous Japanese People. A People can today claim to be aboriginal either in its own name or perhaps by virtue of direct succession from an immediate parent People that had itself already claimed to be the aboriginal People there. But, a specific People cannot suddenly claim to be aboriginal, solely by virtue of some recently alleged genetic descent from a culturally remote or unrelated ancient People with a different name. Today turning to antiquity to make an aboriginal claim in its own name, a distinct People needs to show not only some credible genetic roots but also a continuing socio-cultural identity that, without a break, reaches back across each century to the relevant historical time.

Among the distinct Peoples now living in a region, the one with the best claim to be aboriginal is the named People that was there first in time. Without reference to numbers, this now existing aboriginal People is distinguished from the other current local Peoples which subsequently either were formed in the land (indigenous) or came there via conquest, migration, and settlement.

For example, 1867 saw the creation of a new country called “Canada.” The founders intentionally crafted a new “political nationality” to unite several mostly settler populations with contrasting self-identifications, largely based on differences of language, religion and ancestry. But across the 20th century, Canada completed its own trajectory “from colony to nation.” According to the Supreme Court of Canada, a specifically “Canadian” People gradually emerged via a process of general self-identification. Because of home birth, this nascent Canadian People as such is certainly indigenous to Canada. Nonetheless, the North American Indian tribes there significantly remain the “First Nations.” They are still among the aboriginal Peoples of Canada, though some Indian bands now number only a few hundred individuals. Nor can their special status as “first in time” be erased, because the subsequently born “Canadian” People is also indigenous or because the First Nations are now just a small fraction of Canada’s population.

Like Canada’s First Nations, the Jewish People has the strongest claim to be the aboriginal People in its ancestral homeland, though for long centuries, Jews there were just a small percentage of the local inhabitants. Nor is this Jewish claim to be the aboriginal People there now weakened because: (i) the majority of Jews have at various times lived elsewhere; (ii) Jews are now once again the local majority; or (iii) local Arabs after 1967 generally opted to rebrand as the distinct “Palestinian” People which as such is also indigenous.

Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas denies that Jews are “a People” within the context of the doctrines of aboriginal rights and the self-determination of Peoples. Yet the rejection of Jewish people-hood requires a wholesale denial and repudiation of recorded history and physical evidence—the books of the Greeks and the Romans, the entirety of the biblical corpus including the Old and New Testament as well as large sections of the hadith of the Prophets, archaeology, basic methods of dating artifacts—stretching across millennia that shows that the Jewish People is among the oldest of the world’s Peoples.

Early sources also prove Mideast man understood the idea of people-hood, which is not a retroactive imposition by Westerners. For example, self-identified “Jews” regarded people-hood as one of the motors of world history, as in the biblical Book of Genesis, from around 600 BCE. Referring to a popular name and also to shared ancestry, territory, language and achievement, Genesis (in the story of the tower of Babel and elsewhere) describes sociologically what it means to be a distinct People alongside other named Peoples. Now, 30 years of genome research has also produced a new kind of evidence showing that most of today’s Jews are to an appreciable extent genetically interrelated and significantly descended from Jews of the ancient world.

There are also directly relevant treaties which are the highest source of public international law. To the point, declarations, resolutions, and treaties from the First World War and the subsequent peace settlement explicitly recognize the Jewish People’s historic connection to its aboriginal homeland. And, two of those treaties explicitly call for “facilitated” Jewish immigration and “close settlement by Jews on the land.” For example, the Senate-ratified 1924 Anglo-American Treaty “consents” to Jewish settlement, everywhere west of the Jordan River. With juridical precision, the 1948 Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel refers to a “natural and historic right” to “the birthplace of the Jewish People,” where “Jews strove in every successive generation to re-establish themselves.”

***

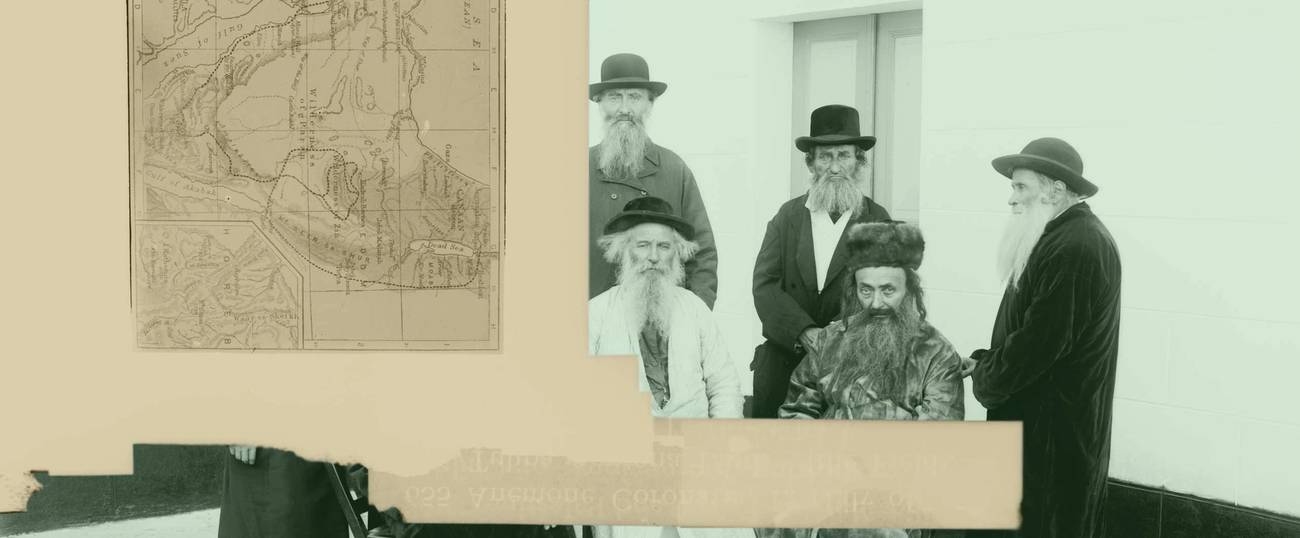

Aboriginal rights characteristically include access to and use of tribal lands, including sacred sites. Jews have always claimed rights to visit and/or dwell in their ancestral homeland. And, they have stubbornly done so for more than two millennia. Across the centuries, some self-identified “Jews” always lived in their aboriginal homeland; and some other Jews, whether from the Mideast or abroad, persistently perceived a duty and desire to join them there.

Jews were most probably the local majority throughout the Roman period. Then, several million Jews worldwide felt a religious obligation to famously make steady, annual payments for the upkeep and ceremonies of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Roman emperors repeatedly affirmed the right of Jews throughout the Empire to contribute to the Temple’s expenses. The Second Temple was also the focus of widespread Jewish pilgrimage from the Mediterranean lands and beyond.

After the 70 CE destruction of the Second Temple, Jews from near and far continued pilgrimage, but now with more focus on sacred sites like the Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron. Far-flung Jewish communities of the Roman Empire joined synagogues elsewhere in offering yearly payments in pure gold (aurum coronarium) to support their religious leaders in Palestine until the Jewish Patriarchate there was abolished in the early fifth century CE. Roman emperors explicitly confirmed this contested right of Jews to collect the aurum coronarium and send it to Palestine. This ancient practice and its imperial confirmation were key expression and recognition of organized Jewry in the Roman Empire.

For around 1,500 years after the abolition of the Palestinian Patriarchate, Jewish communities worldwide regularly contributed to the halukka (Hebrew: חלוקה), a fund to help pious and/or indigent Jews living in “the land of Israel” (Hebrew: Eretz Israel ארץ ישראל). With respect to obligations of charity, Jewish Law (Hebrew: halacha האלאכהא) exceptionally prioritized helping poor Jews of Eretz Israel over indigent Jews in the diaspora. Similarly recognized for centuries was individual and collective Jewish responsibility to give alms to support Jews traveling to Eretz Israel, whether for pilgrimage or settlement.

Reciprocal influences of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam have been perennial. But, the two later faiths generally acknowledged some significant derivation from Judaism, as evidenced by both Gospels and Koran. Especially during their respective periods of local rule—Christians and then Muslims were usually aware of a broader context, in which the Jewish People had a special connection to the land of its birth. There, Jews were subject to permanent discrimination, periodic persecution, and episodic restriction. But, across the centuries, minority status there generally did not preclude Jewish entry, sojourn, and settlement. Nor are millennial rights to such longstanding aboriginal practices diminished, because today Jews are once again the majority in their ancestral homeland.

Jews joining other Jews in Eretz Israel are therefore entirely unlike the 17th-century Pilgrim Fathers who built English settlements in America, where they had neither ancestors nor native kin. The Jewish People in its own aboriginal homeland can never be compared with Dutch Boers in South Africa or French colons in Algeria. The presence of Jews in their ancestral homeland has always been legitimately aboriginal, not an expression of colonialism or imperialism. The shared nature of this aboriginal understanding among Arabs emerges from two contrasting, early Arab responses to Zionism.

Yusuf Ziya Pasha al-Khalidi was for ten years mayor of Jerusalem, where Jews were already the local majority. As a Muslim, an Arab and an Ottoman subject, he wrote (March 1, 1899) a letter opposing Zionism to the chief rabbi of France, Zadok Khan. Yusuf Pasha detailed why he thought Zionism impossible. But at the same time, he validated the Jewish claim to be aboriginal there: “Who can contest the rights of the Jews regarding Palestine? Good Lord, historically it is really your country!”

More positive to Zionism was the Hashemite Prince Feisal ibn Hussein, principal Arab delegate at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. There, American Zionist representative Felix Frankfurter got from Feisal a March 3, 1919, letter saying: “We will wish the Jews a most hearty welcome home.” Referring to Zionism, Feisal acknowledged: “The Jewish movement is national and not imperialist.”

It is a fact that though some Jews always preferred staying in their homeland, others were continually moving in and out. Nor should it be presumed that this migratory pattern only pertained to Jews. Across the centuries, other ethnoreligious components of the local population (e.g., Muslim Arabs) also engaged in significant migrations. Millennial mother-to-daughter continuity was not a strong pattern in this Afro-Asian corridor. During the last thousand years, the population there occasionally dropped to remarkably low levels. Such rounds of radical depopulation were then from time to time somewhat reversed—including by repeated waves of fresh migrants drawn from various ethnoreligious groups, from adjacent regions or further afield. Not so completely different from the others, Jews maintained their local presence mostly “relay race” style, with newcomers taking the baton from existing Jewish residents. But whether coming or going, Jews always saw themselves as a distinct People with the strongest claim to be aboriginal there. This Jewish self-perception was acknowledged by non-Jews, both Muslim and Christian, as evidenced by the responses of leading Muslims to the early Zionist leadership, and, even earlier, by Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1799 proclamation inviting Jews to hasten home to rebuild Jerusalem.

Judaism’s marked territoriality was described by former U.K. Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour in 1919:

The position of the Jews is unique. For them race, religion and country are inter-related, as they are inter-related in the case of no other race, no other religion, and no other country on earth. In no other case are the believers in one of the greatest religions of the world to be found (speaking broadly) only among the members of a single small people; in the case of no other religion is its past development so intimately bound up with the long political history of a petty territory wedged in between States more powerful far than it could ever be.

***

Probably the oldest continuously-functioning legal system anywhere, Jewish Law has always insisted that the Jewish People has, at the very least, rights of entry, sojourn, and settlement in Eretz Israel. How should we approach this longstanding phenomenon? Comparative law is an option that directs attention to the role that history and civilization play in the aboriginal case law of the Supreme Court of Canada. There, in a purely secular context, anthropological data—like Judaism’s persistent emphasis on God’s gift of Eretz Israel to Abraham and his descendants—would be regarded as historical evidence of the continuing importance of that particular land in the distinct culture of that specific tribe.

The Jewish People is aboriginal to Eretz Israel just as are the First Nations to their ancestral lands in the Americas. The Jewish People claims both aboriginal and treaty rights in parts of its ancestral homeland. Aboriginal and treaty rights are also claimed by the aboriginal Peoples of Canada. They strongly believe that their sovereign rights to their tribal lands extend back to the beginning of time—long before the origins of European, international, and Canadian Law. In the same way, the age-old Jewish People’s claims in its ancestral homeland reach back to antiquity and thus antedate the post-Classical birth of Europe and the Islamic civilization.

Common Law courts began recognizing aboriginal rights in the 19th century. From 1982, the rights of the “Aboriginal Peoples of Canada” have featured in Canada’s Constitution Act. The Supreme Court of Canada has decided that, where a First Nation maintains demographic and cultural connections with the land, aboriginal rights can survive both sovereignty changes and the influx of a new majority population, resulting from foreign conquest. Dealing with claims of right on all sides, the Court seeks to juridically reconcile subsequent rights of newcomers with prior rights of a First Nation.

Today, aboriginal rights are also an important topic in Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, and now receive more attention internationally. Pertinent to the millennial phenomenon of aboriginal rights is the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007). This notably lacks a legal definition of “indigenous People.” In the same way and for the same political reasons, international law has never been able to formulate an agreed legal definition of “a People” for the doctrine of the self-determination of Peoples.

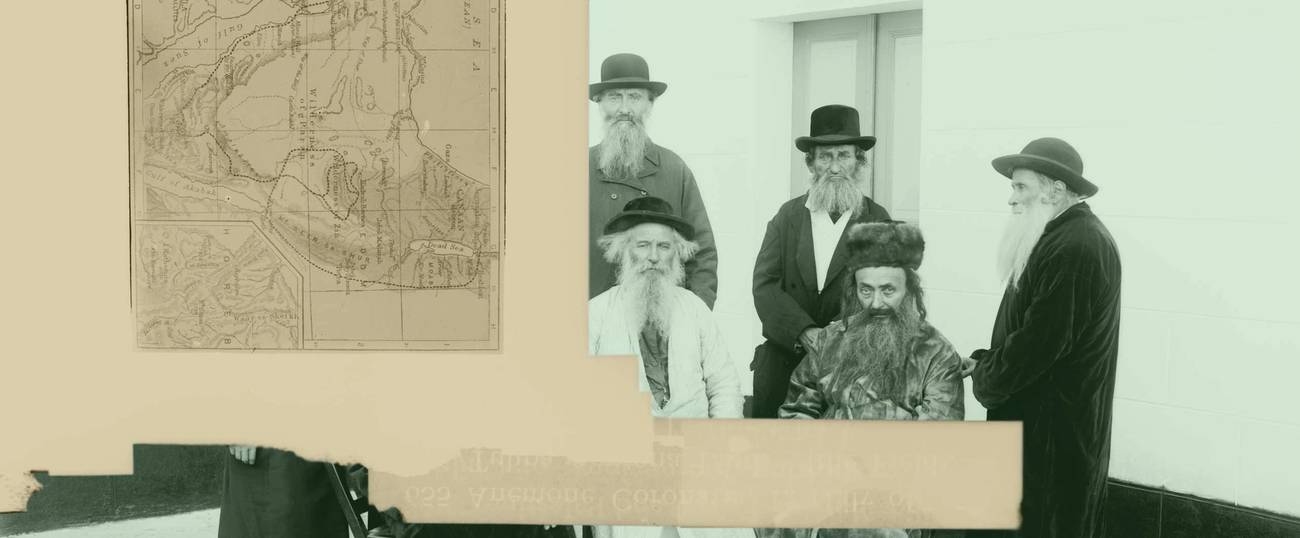

Of all extant Peoples, Jews have the strongest claim to be the aboriginal People of Eretz Israel. There, the Hebrew language (biblical Hebrew: yehudit יהודית) and Judaism gradually emerged, leading to the birth around 2,600 years ago of a distinct People that self-identified as Yehudim (יהודים). Earlier, the Holy Land was home to their immediate ancestors, including famous personalities like Kings Saul, David, and Solomon. There were also other local Peoples—like the Philistines, Phoenicians, Ammonites, Moabites, Edomites, and Samaritans. But with the exception of the few surviving Samaritans, all of those other ancient Peoples have long since vanished. Nobody today is entitled to make new claims on their behalf, including by reason of supposed genetic descent that is only recently alleged and without sound basis in either history or genome science.

What of the Arab People? The great Arab People of history is aboriginal to Arabia, not the Holy Land. Judaism, the Hebrew language, and a self-identified “Jewish” People were already in Eretz Israel about a thousand years before the ethnogenesis in Arabia (circa 600 CE) of the Arab People, the birth of which was approximately coeval with the emergence of Islam and Classical Arabic. Nor traditionally did this Arab People claim to be aboriginal to Eretz Israel. To the contrary, Arabs always knew the Koran to say that Allah had promised “the Holy Land” to the Jews, all of whom would return there by Judgment Day. Moreover, erudite Arabs were aware of their own narrative that celebrated the 7th-century Arab conquest of a Byzantine-Roman province already inhabited by Jews, Samaritans, and Greeks.

Under Muslim rule, Jews there suffered persistent discrimination and periodic persecution. But, neither the Arab People nor subsequent Muslim invaders succeeded in eradicating local Jews or bringing an end to enduring links between the great Jewish People and its aboriginal homeland. To the contrary, Jews continued to stubbornly exercise millennial rights of entry, sojourn, and settlement—and, even more so after the mid-19th century. Result? Jews legitimately became the majority in Jerusalem as early as the 1860s. And today, Jews are legitimately the majority between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.

The last 150 years have witnessed several failed attempts to curtail Jewish migration. For example, the 1939 U.K. White Paper announced British policies signaling an early end to Jewish migration to Mandate Palestine. But, Jews boldly exercised their aboriginal rights of entry and settlement in full defiance of the U.K. government, especially after the Second World War. Then, Jewish rights of entry and settlement were championed by the USSR and the United States. A glance at the diplomatic archives from 1947 and 1948 suffices to remind that the war then launched by the Arab States was as much a failed attempt to stop Jewish migration as to frustrate the partition of Mandate Palestine.

Despite all obstacles, Jews still continue to exercise their enduring rights of entry, sojourn, and settlement. Thus, the Jewish People can now draw increasing benefit from the key doctrine of the self-determination of Peoples, which normally allocates territory by the national character of the current local population. It is not easy to understand how anybody could think that the Jewish People might somehow have lost fundamental treaty rights and millennial aboriginal rights, just because the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (1948, 1967) twice volunteered to initiate armed attacks, or because the U.N. Security Council wishes to abolish existing Jewish rights by fiat, outside of governing legal definitions and structures.

Allen Z. Hertz was senior adviser in the Privy Council Office serving Canada’s Prime Minister and the federal cabinet, including with respect to aboriginal issues. He formerly worked in Canada’s Foreign Affairs Department and earlier taught history and law at universities in New York, Montreal, Toronto and Hong Kong.