Jews Without Israel

Why do American Jews imagine that the political universalism that exceptionally coheres in the United States should apply in an ethnoreligious nation?

It might be a terrifying thought for many American Jews that the price of their own survival in America might one day be to give up their support for Israel and Zionism. But to the few Jews who think this is precisely the price that must or should be paid, it has become necessary, even urgent, to steer the majority of fellow American Jews away from Zionism and Israel, supposedly for their own good. Given that most Jews still believe that both their Jewish and American identities should lead them to support Israel and Zionism, getting them to move away from this fundamental belief can only be attained by presenting an alternative vision that carefully masks the fact that it spells out the end of Israel. Presenting such a vision depends on the invention of an Israel, a Palestine, a Middle East, and for that matter, a world, that do not exist.

The survival, prosperity and thriving of Jews in America has always depended on America being the country where anyone—truly anyone—arriving on its shores could become fully and completely American. Whether in Hollywood or literature, or through their participation in the causes of civil rights, social justice, and immigration, Jews have played an important role in telling this story of the ideal America—open, welcoming, and inclusive.

This idea of the universal America is as inspiring as it is exceptional. The United States is the only country that was purposefully built on universal ideals—if not always their practice—and on the constant effort to create a nation held together by the Constitution. But while Americans might acknowledge their country’s character, they rarely wrestle with the obvious implication that among the world’s countries, theirs is the exception rather than the rule. Certainly, when it comes to the ideals of political organization, the rest of the world’s countries are not universal nations, and almost none of them aspire or even pretend to be so.

Ever since the bloody 20th-century collapse of empires, the Earth’s landmass is divided between nation-states. Those nation-states are almost all based on a single dominant national, ethnic, linguistic, or religious group, often with some other national, ethnic, linguistic, or religious minorities. Even when these nation-states are nominally secular there is rarely any question as to the dominant national religion or origin-story. In that respect, the State of Israel, as the nation-state of the Jewish people, with an Arab national, ethnic, linguistic minority, is well within the global norm. Israel makes perfect sense.

It is true that not every national, ethnic, linguistic, or religious grouping has been able to achieve independence in their own nation-state. Some have tried and failed and perhaps continue to try; some are content to live as an ethnic minority among others; and most national ethnic linguistic groups, typically being very small, have never achieved statehood. Yet, the historical and global direction has been unmistakable: From the Austro-Hungarian to the Ottoman, British, and Soviet Empires, from Indochina to Yugoslavia, and even to tiny Czechoslovakia—as empires and dictatorships collapsed, the drive has been toward smaller and smaller national-ethnic political units.

Most Americans are bewildered by the global organization into ethnic religious national states, which gathered force in the wake of two world wars. Some Americans even spew the word “ethnostate” as if to signify some terrible form of political organization—willfully ignoring and even deriding the fact that almost all states are national, ethnic, religious political creations.

The idea that peoples and nations should govern themselves rather than being the subjects of empires has frequently underpinned liberty and progress for the people in those newly created states. The ideal of equality between people in the wake of the fall of empires was achieved precisely through the equality of sovereign nations and within nation states. These are the central tenets of the post-WWI and WWII international order, the principle of the sovereign equality of all its members and of equality of citizens within their separate national states. This emerged from the understanding that the spread of democracy and the rule of law for all is facilitated by the solidarity among the members of the nation, which rests on deeper historical, cultural, ethnic, and linguistic bonds.

Israel, as the nation-state of the Jewish people, with an Arab national, ethnic, linguistic minority, is well within the global norm. Israel makes perfect sense.

Contrary to the current American tendency to pit its idealized notion of “civic nationalism” against “ethnic nationalism,” in almost all other countries these two ideas are deeply intertwined. The attainment of civic equality for individuals, almost everywhere, depend on them being members of ethnonational states. The willingness of people to share a one-person, one-vote political unit is substantially increased when members of that unit believe they have something deep that binds them together, and that they are governed by “their own” rather than by outsiders. In that, Israeli democracy is again entirely normal.

Civic equality also depends on the members of the national, ethnic, linguistic minorities being full citizens of the state—as Arab citizens of Israel are—and them being given the ability to collectively express their culture and language, as again is the case in Israel. In fact, when Israel is measured by the EU guidelines on how nation-states, which are the European norm, should treat their national, ethnic, and linguistic minorities—for example in providing schooling, government services, and road signs in the minority’s language and providing the ability to celebrate holidays—Israel emerges with strong marks. What makes this achievement especially impressive is that Israel operates in the now rare situation that its minority belongs to the dominant national ethnic linguistic majority in the region—most of which is still officially at war with it, and continues to deny the right of the Jewish people to self-determination in any borders. A fair observer might remark on the fact that the status of the Arab minority in Israel during wartime is better than that of minorities in many countries which are at peace.

It is actually when the political structure of a newly established state is highly incongruent with its ethnic makeup that the state is far more likely to break down into dysfunction. The high correlation between multiethnic states with at least two or three significant national ethnic groups, and civil war, poverty, and low levels of development, is no coincidence. Lebanon is but a recent cautionary and tragic tale. Typically, such states can be held together only through dictatorial rule by a Tito or a Saddam Hussein. The failed American effort to export democracy to Iraq’s multiethnic structure is a tragic case in point of American blindness to the deep connection between civic equality, democracy, and the existence of a clear dominant ethnic religious linguistic majority in a defined nation-state.

But even in the United States, the universal ideal is challenged by the longtime vision that if America is not white and Christian, it could not be properly considered America. That vision of America never went away and continues to wage its own battle for America’s soul. For much of America’s existence it was possible for it to project itself as universal while continuing to fundamentally be white and Christian. But demographics and civil rights have strained that illusion. One could even argue that post-Obama Trump’s America is in the midst of a grand struggle over this question at its very core: If forced to choose, could America truly be a universal nation of all people for all people, or is it fundamentally a white and Christian nation, whose roots are in Europe?

It seems like a no-brainer that the victory of a universal vision of America is the one that Jews should support. Unfortunately, many Jews have discovered in recent years that under the mantle of “intersectionality,” groups such as the Women’s March, Dyke March, and even large swaths of Black Lives Matter—proclaiming themselves to represent the universalist vision of America—have coalesced around a vision of America that is both identitarian and resolutely anti-Zionist.

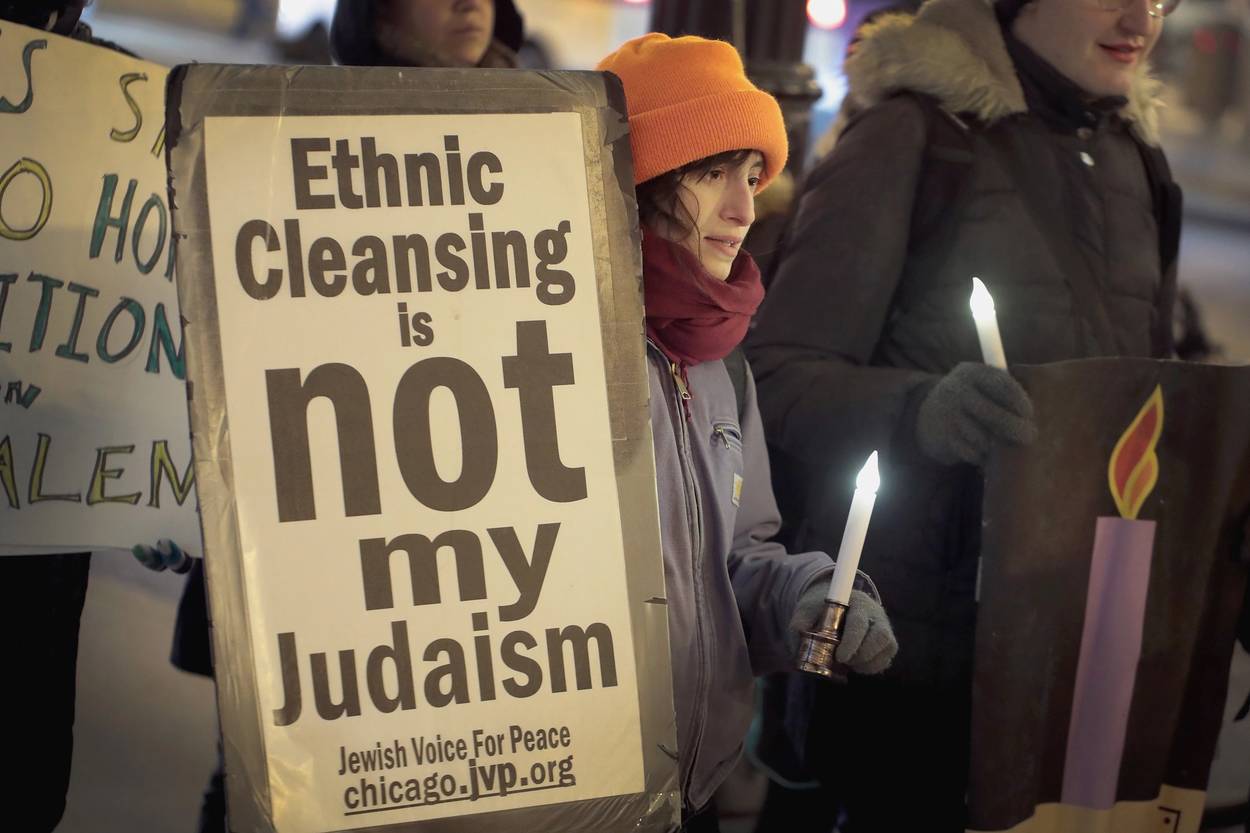

Whether you believe that anti-Zionism is not anti-Semitism, or whether you believe it has become the new shiny and respectable veneer behind which anti-Semitism hides—as we do—there is no question that professed and vocal anti-Zionism has become the price of entry of Jews into progressive spaces. Jews, who traditionally considered themselves as bulwarks of progressive movements and causes in America, have discovered that they have been excluded. As an invitation to a Juneteenth rally stated so eloquently: “Open to all, minus cops and Zionists.”

Between those two massive forces vying for America’s future, it appears that at least some Jews have become convinced that the survival of Jews in America would be better served by the success of this universalist coalition—and if the price of that be forswearing Zionism and Jewish self-determination, so be it. It has become a matter of urgency to reassure members of the self-proclaimed universalist coalition of “the left” that American Jews can be counted upon to support the universal vision across the board and not succumb to their tribal instincts when it comes to Zionism and Israel. Where the left celebrates a multiplicity of groups asserting their own identities, American Jews are required to shed their identity in order to be, perhaps, counted.

Knowing that the vast majority of Jews, including in America, are not so ready to give up their support for Israel and Zionism as the price of admission, a new “gateway vision” has been concocted that would serve to steer Jews away from Zionism. The Israel/Palestine imagined recently by Peter Beinart, for example, is designed to sound very much like the state American Jews inhabit, or believe they inhabit—one of equality, diversity, pluralism, and most importantly, the ability to live life freely and safely as a Jew in a non-Jewish majority country. That all experience from failed multiethnic states points to the fact that this Israel/Palestine country cannot exist peacefully and safely (certainly not for Jews), and that it would descend (yet again) into bloody civil war, makes no difference. The democratic deficit across the Arab world is conveniently ignored. So is the historical record of persecution and pogroms and second-class citizenry of Jewish minorities that eventually resulted in the ethnic cleansing of Jews and Jewish culture from the Arab world.

To help Jews move away from Zionism, Zionist history, Arab and Islamic history, and the contemporary politics of the region, all of these must be distorted beyond recognition. The simple fact that the overwhelming share of Zionists envisioned a state from the beginning, and only called for a more ambiguous “national home” for reasons of feasibility and attainability, especially when facing the empires that controlled the land, is also ignored. Thus, the argument that statehood is not inherent to Zionism has about the equivalent validity of arguing that voting rights are not inherent to feminism because women once were content to fight for elementary school education. Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai, whose plea to have Yavneh and its sages Beinart seeks to emulate, asked for Yavneh when Jerusalem was all but lost and destroyed. Beinart, on the other hand, calls for the effective destruction of Jewish sovereignty in order to get to an impossible Yavneh.

The Yavneh Beinart truly seeks to secure is not in Israel, but in the United States. Beinart could ignore fact, history, and evidence because his essay is not really about how to solve the conflict between Jews and Arabs in the Holy Land, but rather about how to secure the future of Jews, especially like himself, in America. To get there he would use the Jewish state as a sacrificial lamb. This is the reason why Beinart’s essay and numerous one-state essays and proposals published over the years have found no audience in Israel. Israeli Jews recognize none of their concerns in those visions of a magical one-state solution that is the product of narcissistic neocolonialism that draws borders to serve its own needs.

Ultimately, it is up to Jews in America to choose their allies, struggles, and vision for their life as individuals and as a community. It is up to them to decide whether their life in America is better secured by support of Zionism and the Jewish state or not, and whether the spirit of America is more in line with that of Zionism or anti-Zionism. Most Jews in America still believe that Zionism is deeply entwined both with their Jewish and American identities, and that Zionism incorporates both the particular and the universal, and we believe they are right on both counts. But either way—it is their choice. Jews in Israel will continue to celebrate the fact that they finally live in the sovereign nation-state of the Jewish people and can therefore walk this Earth knowing that someone has their back. Jews in Israel viscerally know exactly how fragile is this so-called privilege, that so many nations share, and have absolutely no intention of checking it at anyone else’s door.

Einat Wilf is co-author of The War of Return: How Western Indulgence of the Palestinian Dream Has Obstructed the Path to Peace, a former member of the Israeli Parliament, and served as the Goldman Visiting Professor at Georgetown University. Her Twitter feed is @EinatWilf.

Oren Gross is the Irving Younger Professor of Law at the University of Minnesota Law School.