Cause for Celebration in Syria

The fall of Assad’s pro-Iranian regime is a net gain for the U.S., even if what replaces it isn’t a reliable ally

After last week’s bomb blast in Damascus, which killed four top Syrian security and military officials, including President Bashar al-Assad’s brother-in-law, the momentum finally seems to be turning in favor of the rebels. Assad is not yet out, but he’s certainly down—and it’s clear that the regime’s days in Damascus are numbered. Indeed, its fate may have been sealed more than 40 years ago, when Bashar’s father Hafez first came to power.

The Assad regime is drawn from a heterodox Shia sect, the Alawites, which comprises no more than 12 percent of the population and rules over a national majority of Sunni Arabs, which make up around 60 percent of the country. This sectarian composition is a recipe for instability. Mix in the United States’ 2003 invasion of Iraq, which illuminated the confessional divisions not only in Iraq but also in Syria, as well as the 2011 Arab uprisings that toppled rulers in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya, and the writing on the wall becomes even clearer: Soon, the Sunnis will rule Syria.

What can we reasonably expect in the coming weeks and months?

Don’t expect the Obama Administration to see an opportunity in the turmoil to advance American interests. The White House has stood idly by for 16 months, offering virtually every excuse for its inaction—from fear of empowering al-Qaida, to its complaints that the opposition is not unified. Perhaps most perversely, the administration recently explained that “the CIA’s ability to operate inside Syria was hampered severely by the decision to close the U.S. Embassy” in Damascus. So, while media organizations around the world have sent journalists to report on the Syrian opposition, the well-funded American intelligence community, to hear the White House tell it, is short of resources and initiative.

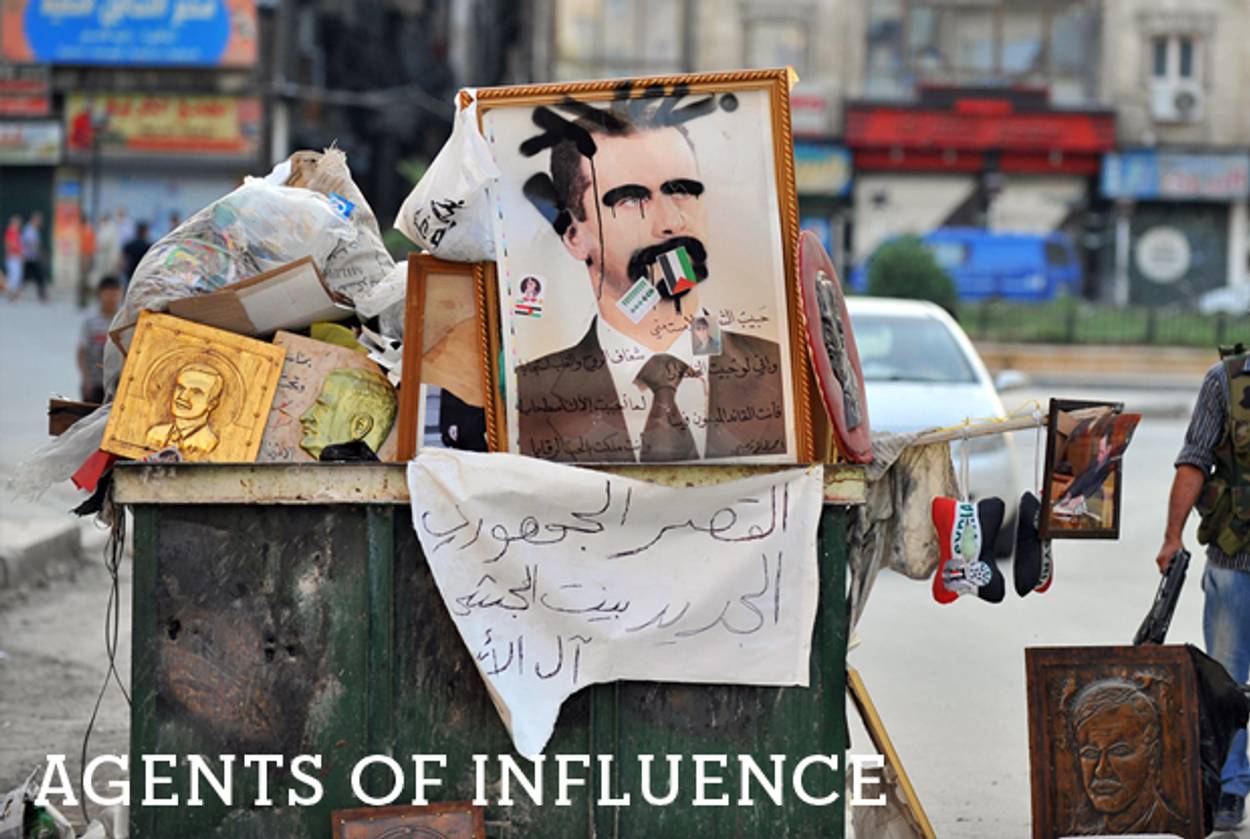

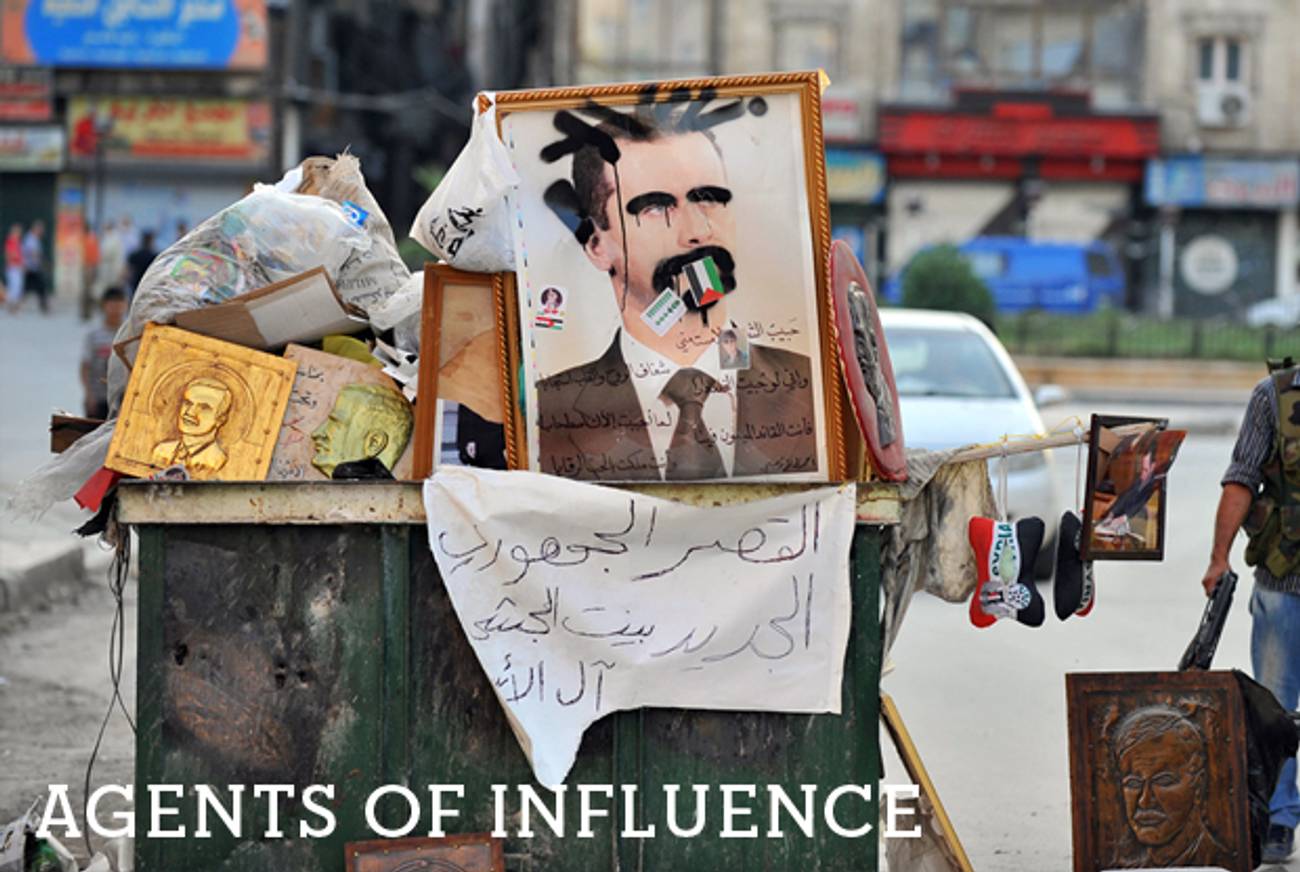

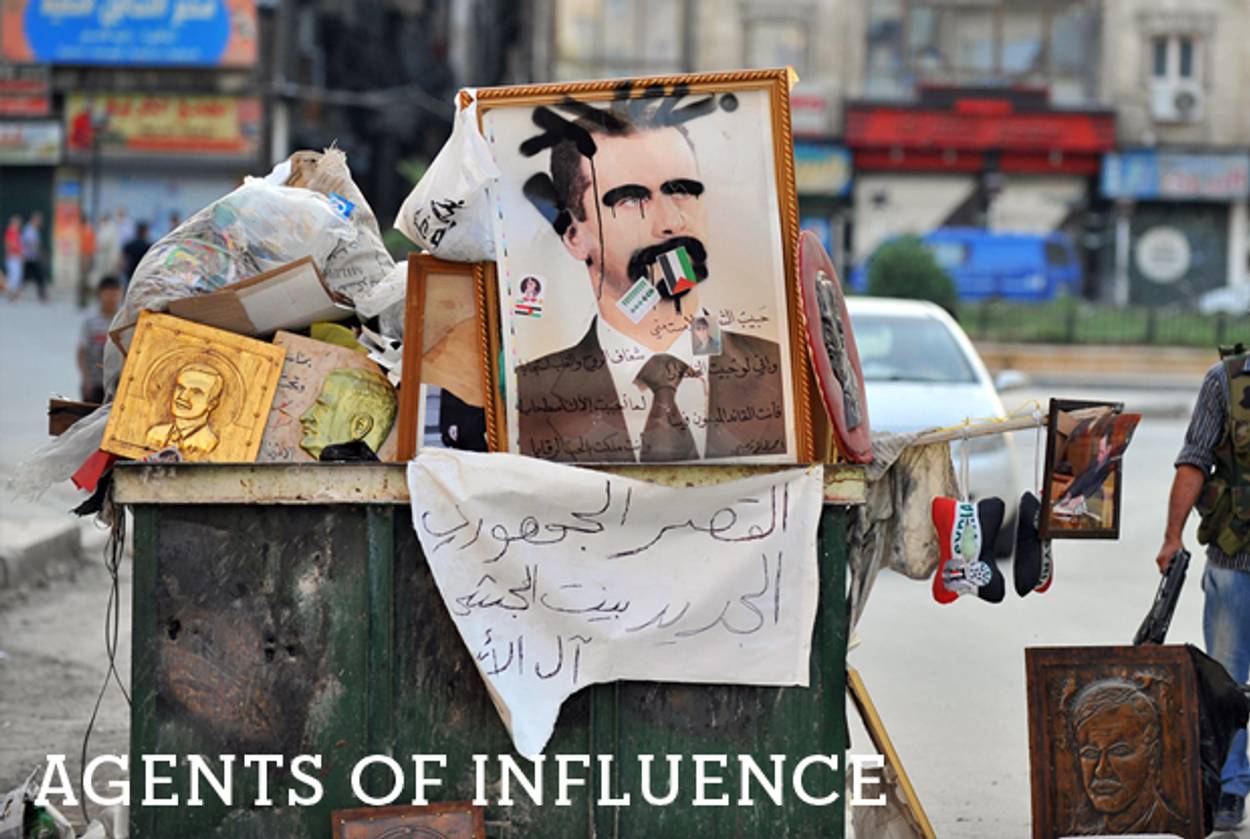

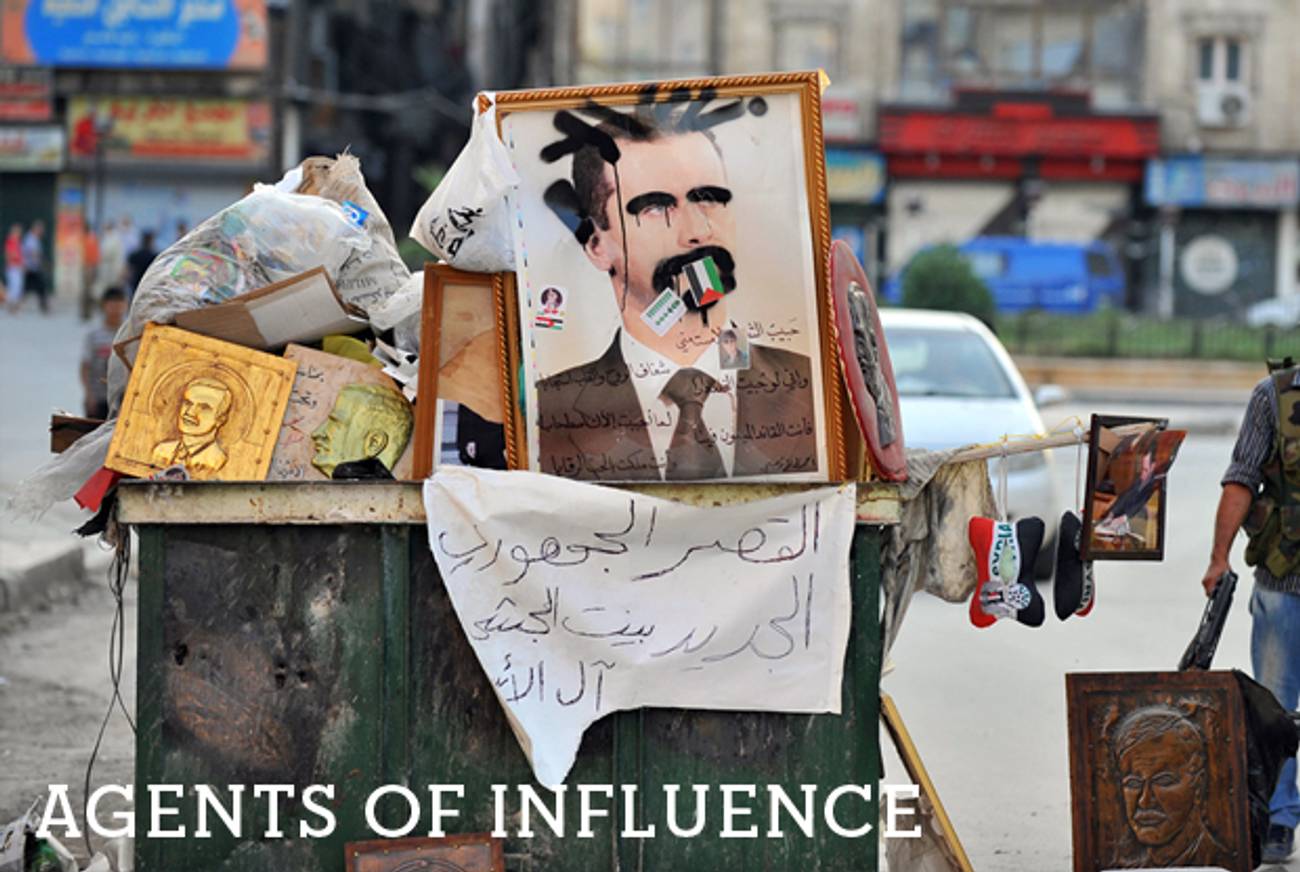

The White House says it seeks an outcome that would preserve Syria’s “state institutions.” However, outside of services like garbage disposal, traffic, and public transportation, the question of “state institutions” is irrelevant: The institutions created by authoritarian police states are meant to protect the regime, not the state and its citizens. For instance, security—one of the most significant institutions in any country—is provided in Syria not by a police force, but rather by the politicized security forces, the mukhabarat. Because the role of this institution is to oppress Syrians, the mukhabarat and other Assad forces have been targeted by the opposition. The uprising’s success can only be defined according to whether or not such institutions are destroyed once and for all. The notion of preserving them is—if not another weak attempt by the White House to pretend it is taking an active role in the conflict—simply delusional.

Indeed, Assad regime institutions have already deteriorated, as evidenced by its loss of control over wide swaths of territory, like the interior and the border areas. When the regime moved to put down the uprising in towns like Deraa, Homs, Deir al-Zawr, and others, rebel forces rose elsewhere, like a game of gory whack-a-mole that exposed Assad’s inability to quell the uprising once and for all. On the peripheries, the Free Syrian Army is fighting the regime for control of crossings on the Turkish and Iraqi borders. Perhaps most significantly, head of Israeli military intelligence Maj. Gen. Aviv Kochavi reported last week that Syrian troops had left their positions on the Golan Heights border in order to reinforce the regime’s defense of Damascus.

Assad loyalists will continue to fight for Damascus but in time will almost certainly have to abandon the Syrian capital for the Alawite enclave along the Mediterranean coast. This is the traditional Alawite heartland, which for a brief time after World War II served as an Alawite-majority state, with its capital in Lattakia. As Tony Badran, a fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, has written, the regime’s massacres in the Sunni-majority towns of Houla, al-Haffeh, and Tremseh are part of an ongoing campaign of sectarian cleansing to create a buffer zone separating the Alawites’ heartland in the coastal mountains from the Sunni interior.

Whether the Alawites are able to make their safe escape to this enclave is another question. To help them secure safe passage, the regime will likely keep its chemical weapons in tow. It is unlikely the regime would use these against Israel or other concerned neighbors like Jordan and Turkey, since they constitute Assad’s insurance policy. So long as he threatens that they might get loose in the chaos, or that he might use them in a final act of desperation, he has some amount of leverage over a White House that has shown its willingness to let Assad play for time.

A much more serious concern is that Assad might turn those chemical weapons on the rebels and their Sunni co-religionists. It’s true that Syria announced on Monday that it would never use the weapons “against its civilians” and would only use them in case of “external aggression,” but it is worth remembering that from the outset of the uprising Assad has described the Sunni opposition as foreign terrorists.

Many have noted the increasing presence of Islamists in the armed opposition and are warning that the United States might need to intervene to protect the Alawites and other minorities, like Christians, from being targeted. For instance, former CIA analyst Bruce Riedel has written that “one of the priorities of the international community after Assad falls will be to protect the Alawite community and its allies from vengeance.” Some in the Obama Administration have echoed Riedel, speaking of a “positive democratic transition that is inclusive, that is tolerant, that creates a place for all Syrians.” But that’s not going to happen right now—not after the Alawites have slaughtered thousands of Sunnis. The White House did not move a finger to save them, so why should step in to protect those who hunted them?

The idea that the Assad regime and its supporters warrant American protection simply because they are a minority group is not only strategically incoherent but immoral. During the course of four decades, the Assads have supported terrorist groups that targeted the United States and American allies in Israel, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Turkey, and the Gulf Arab states. The Assads have allied with virtually every anti-American power for 40 years, from the Soviet Union to Iran. Does anyone believe that in the aftermath of World War II it was the role of the United States to save the Nazis and their allies from the Red Army? Of course not. Political wisdom begins with being able to distinguish enemies from friends, even if those allies are only temporary.

Make no mistake: The fall of the Alawite regime is unlikely to usher in a Syrian government that the United States will be able to consider a reliable ally—and the fact that the Obama Administration has consistently sold the opposition short is not going to help matters. Nor will Sunni rule likely lead to an age of freedom and democracy. It is doubtful that Sunni-led Syria, for the time being at least, will be anything other than an autocracy, like every other Sunni Arab state in the Middle East. No doubt Islamist elements will play a role in the new ruling order, which may also in time pose a threat to American interests, and more specifically to Israel.

However, a large part of strategy is prioritizing threats, and right now the major issue in the region is Iran: Anything that weakens the Iranians is a net gain. There is time enough in the Middle East to deal with other threats, which a post-Assad Syria may well become. The most pressing concern is a scenario in which Assad is camped out on the Mediterranean coast, still allied with Iran and serving as a link to Hezbollah. An Alawite statelet is an outcome that the Obama Administration should seek to prevent.

For those—particularly Israelis—who may come to lament the fall of the Assads, it’s worth remembering that this regime was not a de facto friend that kept the Golan Heights border peaceful since 1973. It was an active enemy. It built a secret nuclear weapons facility meant to manufacture arms targeting the Jewish state, and its chemical weapons were stocked with the same intent. Through its support of countless terrorist groups, the regime killed Israelis, Palestinians, Lebanese, Iraqis, and Americans. Its reckoning and eventual flight from Damascus will be cause for celebration, however brief.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Lee Smith is the author of The Consequences of Syria.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).