Far From Home

On the eve of the Iraqi elections, the daughter of Iraqi Jews mourns the destruction of Baghdad’s once-vibrant Jewish community

As Iraq’s March 7 election draws near, I can’t help reflecting on how far the Iraqi nation, now entrenched in factionalism, has departed from the commitment to multiculturalism so vital to its birth. “There is no meaning in the words Jews, Muslims, and Christians in the terminology of patriotism, there is simply a country called Iraq and all are Iraqis,” King Faisal proclaimed in 1921, soon after the British installed him as king. These were fine words, underscored by a constitution that granted all of Iraq’s indigenous minorities equal rights. But Faisal’s valiant experiment in diversity proved short-lived, as I know all too well—my own family was forced into exile in 1951, after the government decided to eject Iraqi Jews en masse from the country.

Actually, it would be more accurate to say my family exploded into exile, atomizing in the process. Some members landed in Israel, some in Iran, and some in North America; my immediate kin escaped first to India and then eventually to the United Kingdom. The dynamite involved was—as is ever the story with Jews—racial hatred, which played itself out in the Iraqi political arena as an inability to resolve escalating tensions between Arab Nationalism and Zionism.

My family was far from alone in being shattered. Iraq’s entire Jewish population—a community with roots in Mesopotamia that pre-date the birth of Islam by a millennium—was unceremoniously ejected from the country between 1950 and 1951. But first the Iraqi government had “denaturalized” the Jews, effectively making them refugees in their own land and rendering them defenseless against marauding gangs eager to harm Jews in a kind of skewed quid pro quo for the displacement of Palestinian Arabs.

The improved security prevailing in Iraq over the last two years has resulted more from the increased deployment of U.S. troops known as “the surge” than from any deep rapprochement between the country’s religious and ethnic factions. Once the Americans leave, the security situation may quickly deteriorate. I am thankful that I managed to make it safely into Iraq and back home to London in 2004. At the time I was researching a memoir about my grandmother’s life in Baghdad. I felt compelled to go there, driven by a determination to visit the land of my ancestors and to find out whether any ghostly traces remained of my family’s past, or of the wider Jewish community that had so hastily departed, leaving jobs, homes, community property, and business concerns to their own uncertain fate.

I knew that Saddam Hussein had gone on a series of vengeful campaigns of property destruction in the 1970s and 1980s and that numerous synagogues had been razed. (Baghdad once boasted 65 synagogues, which were obliged by law to be less conspicuous along the city skyline than Baghdad’s mosques.) I also knew that the houses and riverside villas deserted by fleeing Jews in 1950 and 1951 had long ago been repossessed, bought on the cheap at government auctions held after liquidators had completed their inventories of frozen Jewish assets. Still, I’d heard that in the Old City one could find cigarette-shaped indentations in the doorposts of houses, to which mezuzahs, long ago pilfered for their silver, had once been nailed, and Stars of David ingeniously incorporated into a building’s brickwork: empty spaces and silent traces, hinting at prior occupancy.

I was to be disappointed in my quest for concrete evidence of Jewish habitation. The Old City is shaped like a clenched fist, with narrow streets and alleyways threading round endless turns that invariably lead you back to where you started. Along with my guide, I spent a day fruitlessly exploring; the old city was protective of its secrets. Not one mezuzah tray nor Star of David was in sight. As we hunted, I cursed my ignorance of my ancestral past and chastised myself for not interrogating elderly relatives about their lives in Baghdad when opportunity allowed. Now, of course, I see each spasm of self-reproach as a reminder of history’s propensity to slip from our grasp even as we cling to preserve it.

My day in the Old City was not entirely lost, however, in that my guide managed to locate the old, and now abandoned, Jewish Community Office on River Street, offering the Muslim caretaker a little baksheesh to smooth our way inside. We found two dusty rooms, each filled with a heap of upturned office furniture resembling a bonfire in waiting. Along the walls, bookcases with smashed glass doors housed ledger books documenting community business of various kinds. I pulled out one tattered and dusty volume, bound in peeling red leather, wanting to take a closer look, whereupon my guide explained, heartbreakingly, that the carefully scripted lists I found in its pages were logs of marriages in the community. By now the caretaker was leery of our unexplained presence and insisted that we leave.

What has since become of the ledgers and marriage registers is unclear, since current reports claim that only eight Jews are left in Iraq today, and no one else could conceivably have an interest in preserving them. When I visited in 2004, the Jews numbered 22, and none of them had visited the Community Office since a Palestinian gunman let loose a hail of bullets in the mid-1990s, killing two Jews and two Muslims before escaping into the crowded streets of the Old City.

Battered by years of persecution, followed by war, then sanctions, then more war, the Jews I found surviving in Baghdad were not the kind of people to mobilize and regroup, to insist on their rights, or to call to account the powers that be. They were anxious only to keep their heads down, so as not to attract unwanted attention, and to go about their business as quietly as possible. That business—insofar as it related to their faith—was to maintain religious observations at Baghdad’s last standing synagogue, the Meir Tweg Synagogue in Betaween, and to tend the Jewish cemetery in Sadr City, which had suffered bomb and fire damage in the fighting of 2003.

I visited both the synagogue and the cemetery when I was in Iraq. The former turned out to be a stupendously grand edifice; two stories high and occupying a full housing block; it had clearly been built to hold a substantial congregation. The central chamber, containing the ark and bimah, was hung with giant chandeliers, while thick Persian rugs lay on the pews. The ark once held the sum of Baghdad’s Torahs, each encased in carved silver, but on my visit there were only 13 scrolls left. The rest had been stolen in an impromptu raid by the secret police in the 1980s and most likely ended up among the haul of Jewish artifacts found by the allies in 2003—artifacts that had been left to languish in a sewage-filled basement at secret-police headquarters.

The cemetery was where I felt most at home in Iraq, surrounded by the silent and comforting presence of my ancestors. The brick tombs were being repaired with funds that came, circuitously, from the Jewish Agency, and their Hebrew engravings, many of which had been badly eroded, were being airbrushed, chemically fixed, and preserved. I presumed that my grandfather was likely buried there, though I quickly gave up trying to find his grave after I recalled that the Jews used to bury several bodies in vertical graves. Instead, I sat down beside an anonymous grave and wondered at the miracle that allowed a fragment of my heritage to remain.

The remaining Jews of Baghdad could not be said to constitute a community. They were merely a tiny remnant of a once-great people, and they now find themselves marooned in a sea of anti-Jewish hostility—isolated, frightened, and largely forgotten. Meeting and talking with them, I found it difficult to believe that Jewish people had joyfully thrived in Iraq. Even in the middle of the last century, when their number had fallen from an historic high of several million to just 150,000, Jews still made up one-third of the population of Baghdad.

The first half of the 20th century witnessed a Golden Age for Jews in Iraq, beginning when statehood granted them full citizenship instead of second-class, or dhimmi, status. Iraq’s Jews clamored to contribute to the country’s early political and cultural flowering. They took up seats in Parliament and advised Arab ministers. They populated the officer class in the army, served in the judiciary, and were particularly active members of Baghdad’s café society. The community produced novelists and poets who wrote in Arabic, founded literary magazines, and established intellectual salons. Iraqi Jews invented the classic musical form known as the Maqaam. They formed several orchestras. One of Iraq’s most popular singers, Selima Murad, was a Jew.

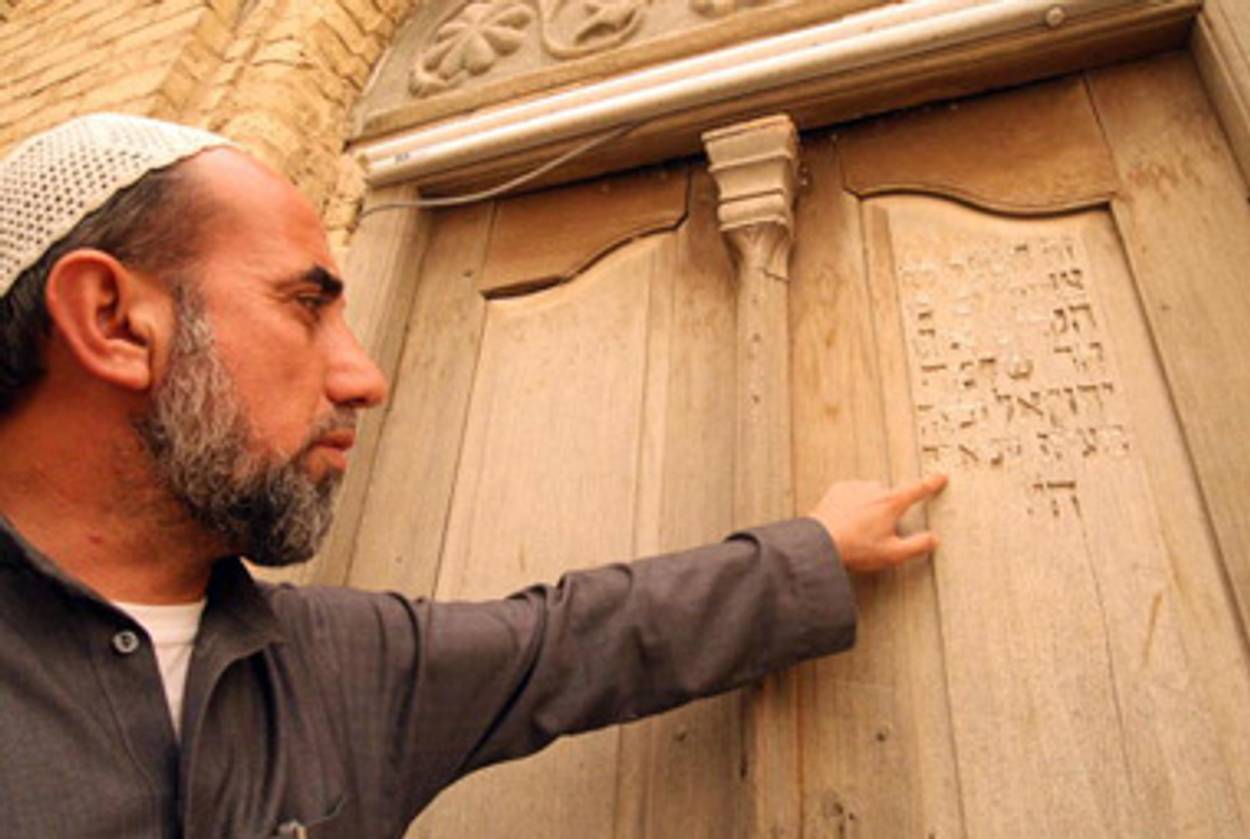

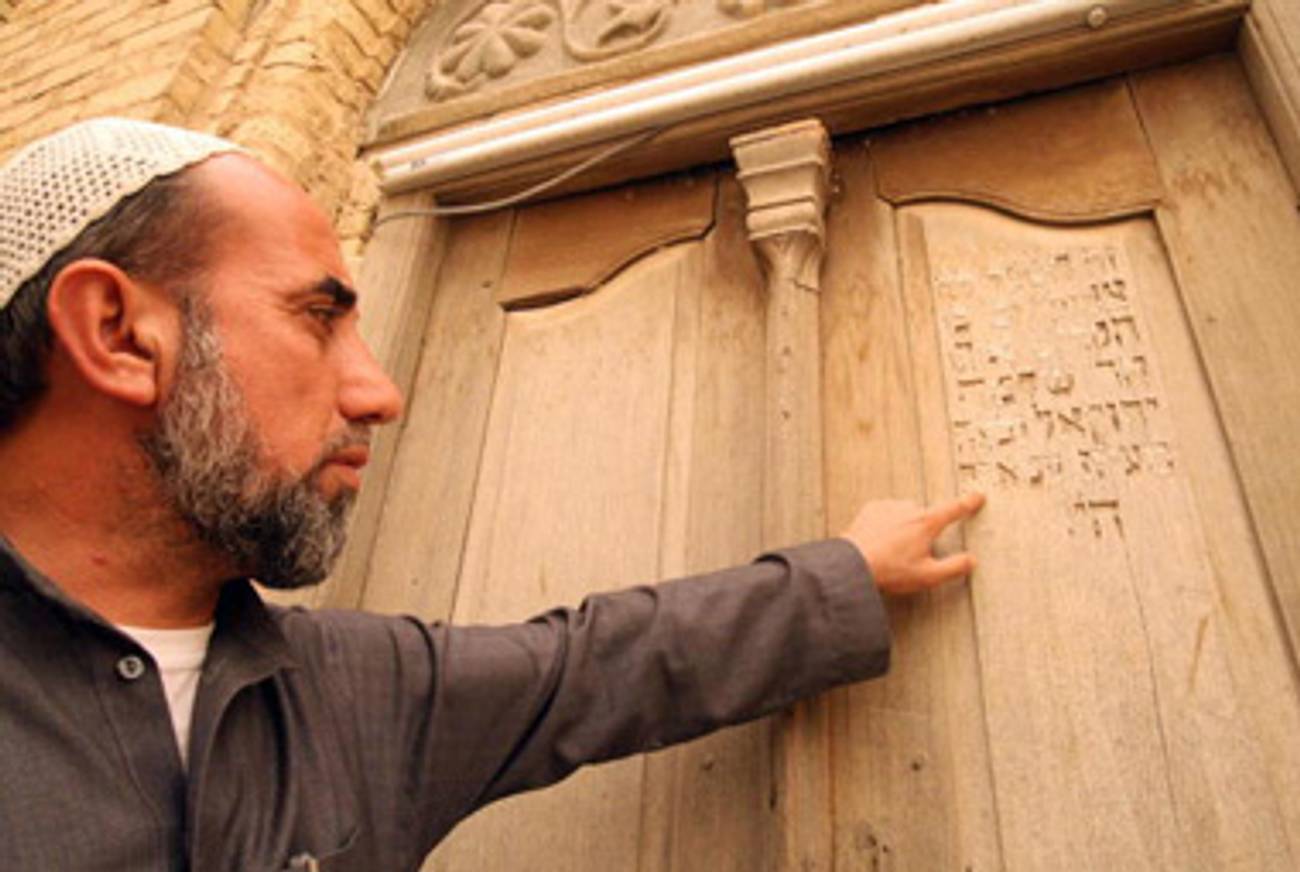

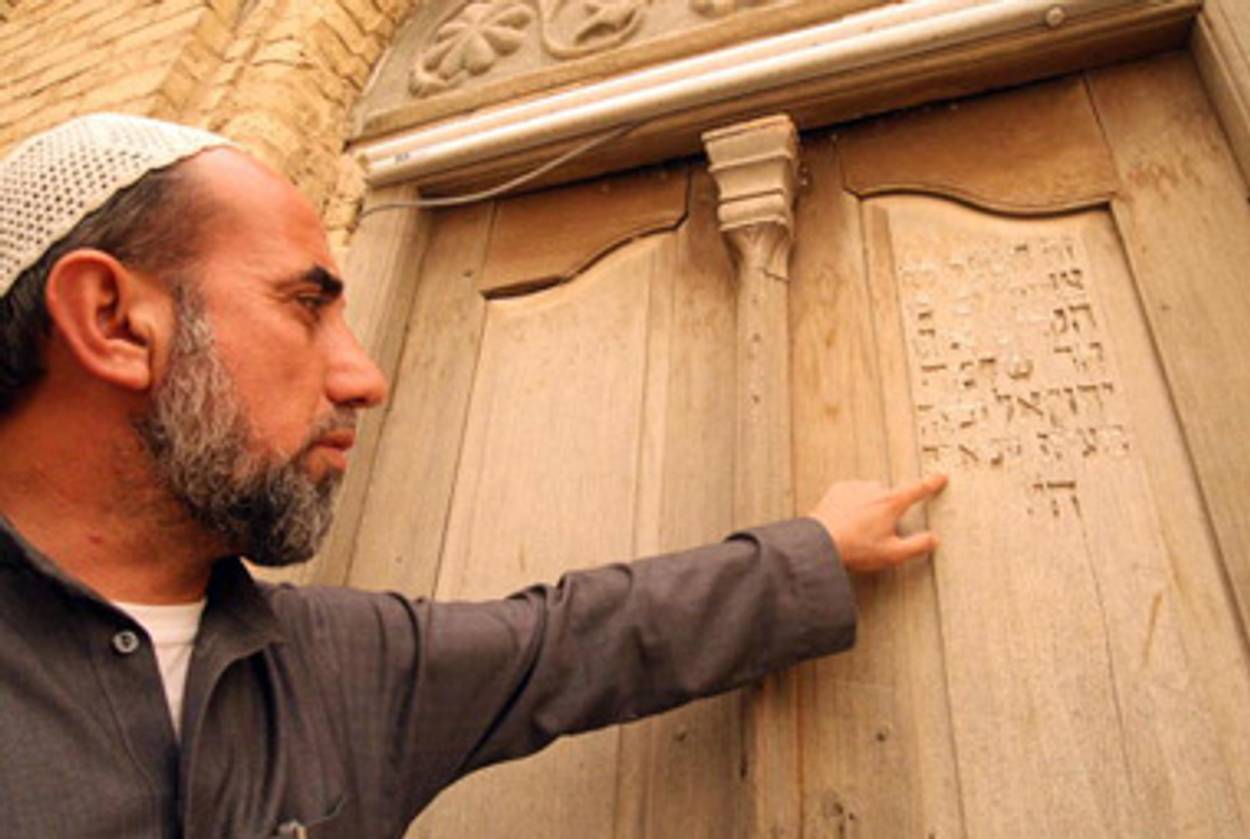

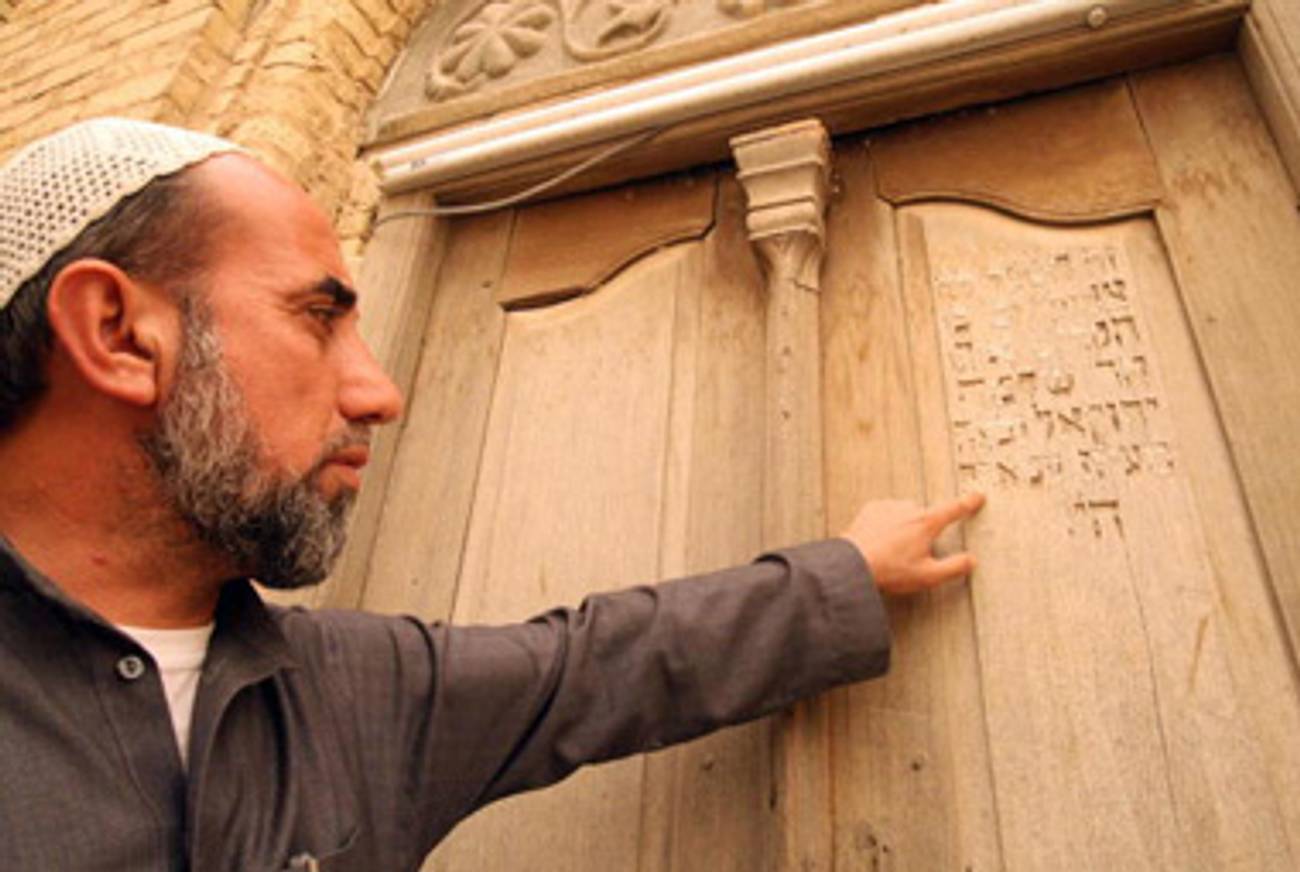

The tragedy is that, in the end, none of this history counted for anything. Up against a powerfully antagonistic political milieu, the community collapsed. The injury that compounds the tragedy is that even now Iraqis are engaged in erasing Jewish history, as if determined to pretend it never happened. Since 2003, Iraqi authorities have repeatedly promised to preserve and maintain the nation’s many Jewish shrines, including the tombs of Ezekiel, Ezra, Daniel, Nehemiah, Nahum, and Jonah. Yet nothing has been done. As for the most magnificent of these sacred sites, the carved tower that marks the tomb of Ezekiel at Al-Kifl, the Antiquities and Heritage Authority has announced that a huge mosque is to built there, and already Hebrew inscriptions and ornaments are being removed from the site as part of the “renovations.”

When I talked to Samir Shahrabani, one of Baghdad’s last Jews, he reflected soberly. “We have high tower in the desert,” he said. “Each day this tower sinks, one inch by one inch. One day we will have nothing. This is how we are.” He was talking metaphorically, of course, but in light of the plans to “renovate” the shrine of Ezekiel his words take on a sharper meaning. Today there are eight Jews left in Iraq. One day, in the not too distant future, there won’t be any.

Marina Benjamin, a journalist living in London, is the author of Last Days in Babylon, a memoir about her Iraqi grandmother and the lost Jewish community of Baghdad.

Marina Benjamin, a journalist living in London, is the author of Last Days in Babylon, a memoir about her Iraqi grandmother and the lost Jewish community of Baghdad.