Fifty Years of Occupation

Can anything change the status quo in the territorial dispute between Israelis and Palestinians?

Shortly after I moved to Ramallah in the spring of 2011, I began jogging in the rolling hills around the city. The hills gave way to lush valleys and wadis that made for ideal running paths. From the ridge line around the city, I could faintly see the Mediterranean Sea glimmering in the distance. Once I descended into the lush valleys and ran among the olive groves, I felt a million miles away from civilization—and certainly from the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

One evening as I was running with a fellow American journalist, an Israeli military jeep suddenly appeared on the dusty path. There was no convoy of jeeps, nor did the driver appear to be in a hurry. My friend joked that we should stop the soldiers and ask if they were lost.

In all likelihood, these soldiers were simply taking a shortcut to the nearby settlement of Beit El, which houses the headquarters of Israel’s military government. (Israel refers to it as the “Civil Administration.”) With nearby settlements such as Dolev and Halamish, soldiers and settlers working in the Civil Administration often sought shortcuts to work.

Over the last 50 years, popular shortcuts across the West Bank have had a curious way of becoming freshly upgraded roads. One day in the not-too-distant future, my friend and I noted after the jeep jolted us back to reality, our innocuous running paths around Ramallah would probably become part of Israel’s settlement infrastructure.

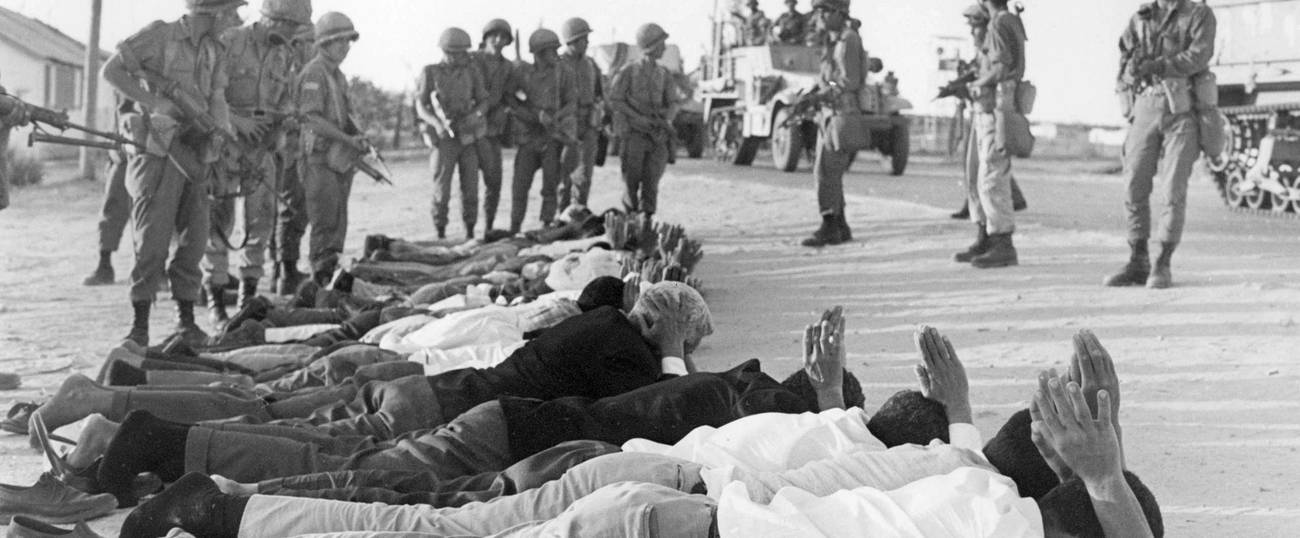

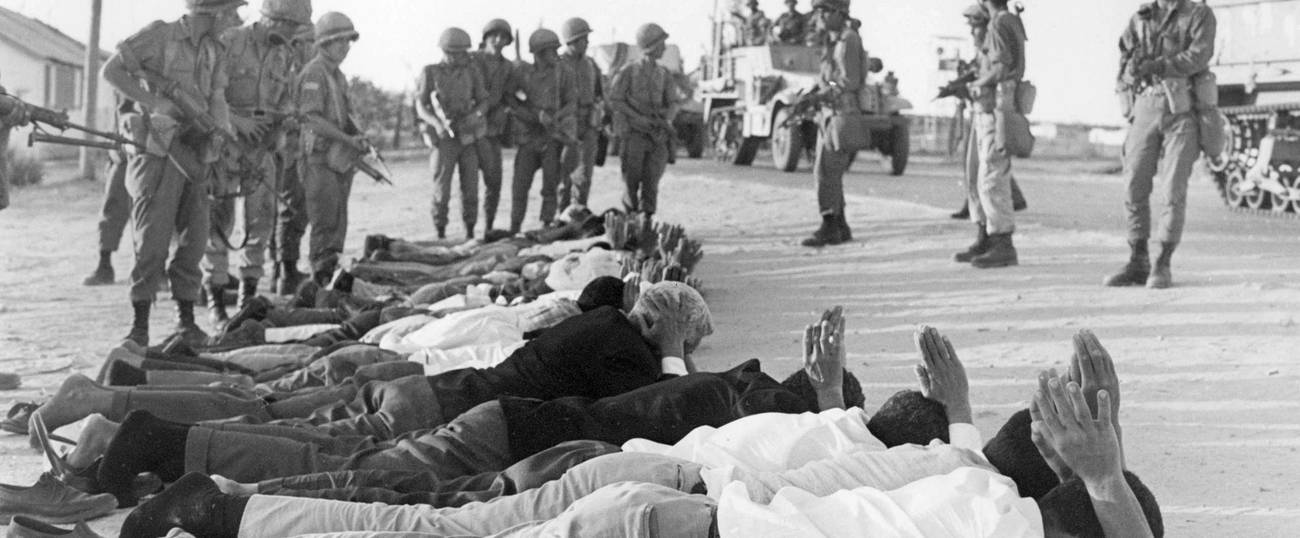

Since the beginning of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem in the aftermath of the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, Israel has used many such shortcuts around the West Bank to entrench its control over the land. This multifaceted process of land expropriation has included the creation of large settlements, infrastructure such as roads and tunnels, the extension of a special “security zone” around the perimeter of settlements that often swallow up Palestinian farmland, and the construction of a wall separating Israel from the Occupied Territories that fails to follow the 1967 armistice line.

The result of this state project—the largest in the country’s history—is a matrix of control in which borders between Palestinian and Israeli land have been rendered meaningless. While the Oslo Accord attempted to give Palestinians limited transitional authority over their affairs and their land, the reality on the eve of the occupation’s 50th anniversary in June is that Israel is the dominant force between the Mediterranean Sea and Jordan River.

So profound is Israel’s hold on the territory that the lack of prospects for peace have failed to elicit passionate debate in the mainstream press even as the occupation enters its 50th year. The discussion about the Middle East is focused on the Syrian crisis, refugees, and the rise of extremist groups such as ISIS.

The settlement project on the West Bank continues unabated, with announcements of ramped-up building in existing settlements and plans to create an entirely new settlement—Emek Shilo—in the northern West Bank. Highlighting the gulf between rhetoric and reality on the question of Palestine, Israel’s unofficial but strong alliance with Arabian Gulf countries such as Saudi Arabia continues to strengthen over mutual distrust of Iran and its interventionist foreign policy from Yemen to Iraq and Syria.

Five years ago, when the region was in the midst of uprisings that carried the possibility of democratic change, the pitch of debate about Israel was significantly stronger. Peter Beinart had released his landmark book about the crisis of Zionism, and with it a conversation inside the American Jewish community about the unsustainability of Israel’s occupation appeared to be underway.

Protests against the Palestinian Authority and its decades of collusion with Israel swept across the West Bank. Young Palestinians inspired by the civil disobedience of the First Intifada organized marches to major Israeli checkpoints and the separation barrier on a regular basis. Just as soon as change was felt on the ground, it was extinguished.

Mahmoud Abbas, currently in the 12th year of his four-year term as leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization, went to the United Nations partly in response to protests about the legitimacy of his rule to lobby for recognition of Palestine as a state. More spectacle than substance, the statehood recognition did nothing to sow unity among Palestinian political factions or slow the pace of Israeli settlement construction across the West Bank.

Ultimately, the uneasy status quo returned, whereby Israel administers the land in any manner it chooses while negotiating episodic bursts of Palestinian resistance. On the eve of Israel’s 50th year of occupation over the West Bank, it is the increasingly strong status quo that is driving conversation about the conflict forward.

***

Nathan Thrall, an analyst with the International Crisis Group and consummate observer of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, adds substantially to our understand of the status quo in his perfectly timed new volume The Only Language They Understand. A collection of his writings from the past five years that have appeared in the New York Review of Books and the London Review of Books, Thrall argues that compromise has only come about when the sides are forced, often through violent means. Thrall constructs a picture of the conflict in which Israel has no reason to alter its footprint in Palestine.

“As Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and East Jerusalem approached its 50th anniversary,” Thrall notes, “it was hard to defend the notion that it was unsustainable. But sustainable is not the same as cost-free. The violence of 2015 and early 2016 was a resurgence of occupation’s costs, which, though unpleasant for Israel, remained the bearable price of holding on to East Jerusalem and the West Bank.”

Thrall arrives at this conclusion after a lengthy description of 30 years of failed efforts to end the occupation that culminated in the Oslo Accord. The concessions that Israel made to the Palestinians in the past were only after significant pressure from the United States, especially from the Carter administration, along with sustained civil disobedience from Palestinians in the Occupied Territories during the First Intifada.

Using the 1982 invasion of Lebanon as one example, Thrall demonstrates that the Arab world has effectively abandoned the Palestinian issue, as Arab countries were not even able to come to the aid of sovereign Lebanon when it was under attack. Israel’s expanding but quiet military and economic relationship with Arabian Gulf countries is proof positive that Jerusalem can continue its occupation while extending its influence in the Middle East.

The strength of the status quo stems from the defeat of the Palestinian unity and organized civil disobedience codified in the 1993 Oslo Accord. As the prominent Palestinian critic of Oslo Edward Said noted in the 1990s, “For the first time in the 20th century, an anti-colonial liberation movement had … made an agreement to co-operate with a military occupation before that occupation had ended.”

The record of negotiations since Oslo, Thrall observes, shows that the Palestinians have demanded no more than what is afforded to them under international law, but Israel claims that such demands are unreasonable and there is no partner for peace. All the while Israel has further entrenched its imprint in the form of roads, settlements, security zones, military-training areas, walls, fences, surveillance towers, and checkpoints.

The consequences of these actions have thus far been manageable, in Jerusalem’s estimation. Given the fever pitch at which Israeli politicians speak about the boycott movement and other nonviolent Palestinian measures, there is a substantial fear that the movement could spiral into something as large as the anti-apartheid boycott of South Africa in the 1980s. But for the moment, Israel has no reason to change the status quo.

And yet, there is another cost military strategists and politicians might not be considering: the cost of maintaining the occupation for Israeli society. In an introspective memoir about a lifetime of crossing the green line and the relationships forged along the way, Raja Shehadeh addresses this question albeit from an unexpected starting point.

A lawyer who founded the human-rights-law organization Al Haq in the 1970s, Shehadeh has written several books on Palestine that go beyond mainstream narratives of the conflict to challenge widely held perspectives on both Israel and Palestine. Palestinian Walks, a book about walking the hills of Palestine (including the running paths I once visited on a daily basis), won the Orwell Prize in 2008.

Timed to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the occupation, his latest volume, Where The Line Is Drawn, is composed of several vignettes on subjects ranging from unlikely friendships to visiting the Jaffa home his family fled after the 1948 war. The central story revolves around his friendship with a Canadian-Jewish immigrant to Israel named Henry. When they first meet, Henry is carefree and open to diverse viewpoints on Israel.

While Henry hesitates to describe himself as a Zionist, he has nonetheless chosen to live in Israel. The relationship between the two friends becomes strained as the fighting intensifies around them in Lebanon and with the First and Second Intifada. As a Palestinian living under occupation, subject to daily humiliation by an occupying army, Shehadeh is angered by Henry’s perceived inaction over the policies of his adopted government. As the conflict intensifies during the Second Intifada, their friendship strains, but it is ultimately Henry’s battle with cancer that brings the two back together.

In one anecdote that demonstrates Shehadeh’s ability to see the good in people regardless of politics, he signs up for a Hebrew immersion course at an ulpan in Jerusalem. He is taken by his Hebrew teacher, an Israeli woman with deep roots in the country. Only Hebrew is spoken in her classroom. After several days of class, Shehadeh becomes infuriated with the course material that describes Palestine as a barren land when the early Zionists arrived at the turn of the century. He gets up in front of the class and passionately tells his fellow students about his family’s life in Jaffa and how the city was a bustling center of commerce and culture. After five minutes, the teacher interrupts to tell him that he has been speaking in Hebrew the whole time. She was a great Hebrew teacher, Shehadeh notes at the end of the scene.

***

On the anniversary of Israel’s takeover of the West Bank, Shehadeh’s narrative of friendship highlights the underlying tension between Israelis and Palestinians. Israel’s ongoing control over Palestine defines relationships along the axes of occupier and occupied. This dichotomy is something that Israelis of all political stripes fail to reconcile. Beyond the discussion points of divine right and even extreme nationalism, Israel’s occupation is a constant source of tension and unease.

The fatigue of maintaining its state project in the Occupied Territories will ultimately prove too big for Israel to bear. Once that fatigue becomes too costly—given the present strength of the status quo, it could be quite some time—Israel will be forced to make compromises to create a regime that is more manageable.

It is here that the comparisons with apartheid South Africa, and specifically a new book by the academic Andy Clarno, contributes to the Israel-Palestine debate. In Neoliberal Apartheid: Palestine/Israel and South Africa After 1994, Clarno charts the rise of private security, “racial capitalism,” and separation in both places over the last 25 years.

Instead of claiming that Israel practices apartheid—and thus focusing on the similarities between South Africa of the 1980s and Israel today (itself a worthy debate)—Clarno demonstrates how South Africa shifted from constitutional apartheid to economic apartheid in the 1990s. Call it what you will, but the ground is fertile in Israel and Palestine for a similar shift in the future.

The end of apartheid in South Africa is one of the few examples of a minority power being defeated by an insurgent liberation movement but losing nothing economically. In fact, the white minority gained access to the international community as a result of the dismantling of its system of racism and intolerance. Today, the majority of the country’s wealth is centralized in white hands, and democratization has not altered the balance of power between the white minority and the black majority. Nearly 25 years after democracy, South Africa is the among the most unequal societies in the world.

This recent history is critical for charting a path out of the morass for Israel and Palestine. Israel, as the dominant power, has already taken most of the natural resources. The creation of settlements in the West Bank and the roads that connect them to Israel could be physical barriers to integration after the conflict ends—in much the same way that the urban planning of Cape Town under apartheid continues to separate blacks and whites today.

Moreover, the Oslo Accord created a donor-aid economy in the West Bank. Palestinians were given access to aid that has made a select few wealthy while handcuffing the Palestinian Authority to the whim of the international community. The effects of the donor-aid economy were visible as millions of dollars in aid money earmarked for Palestinian Authority salaries were withheld as punishment for the PA’s attempt to garner state recognition at the United Nations in 2012.

Fifty years of occupation indicate that the status quo will not end soon. There is no pressure great enough—from the Palestinians, the Arab world, or the international community—to force Israel to change its course in the short- or medium-term. At a time when Israel has more economic ties to the Arab world than at any other point in its history, not to mention an expanding economy, the occupation is simply not costly enough.

Palestinian resistance could make Israel’s state project in the Occupied Territories more costly but as similar examples of undemocratic rule have demonstrated, Israel is its own worst enemy when it comes to the long-term viability of the occupation.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Joseph Dana is a writer living in Cape Town, South Africa.