For Hamas, the Arab Spring Has Been Disastrous—But It Still Has a Stranglehold on Gaza

The group has maintained an uneasy status quo despite losing key allies in Tehran, Damascus, and Cairo

As the Arab Spring heads into its third winter, few regimes in the Middle East find themselves in a worse position than Hamas does in Gaza. The regional upheaval has been a nightmare scenario for the organization, which faces a shrinking list of allies and revenue sources—both problems of its own making, and both potentially disastrous, despite the group’s continued stranglehold on power.

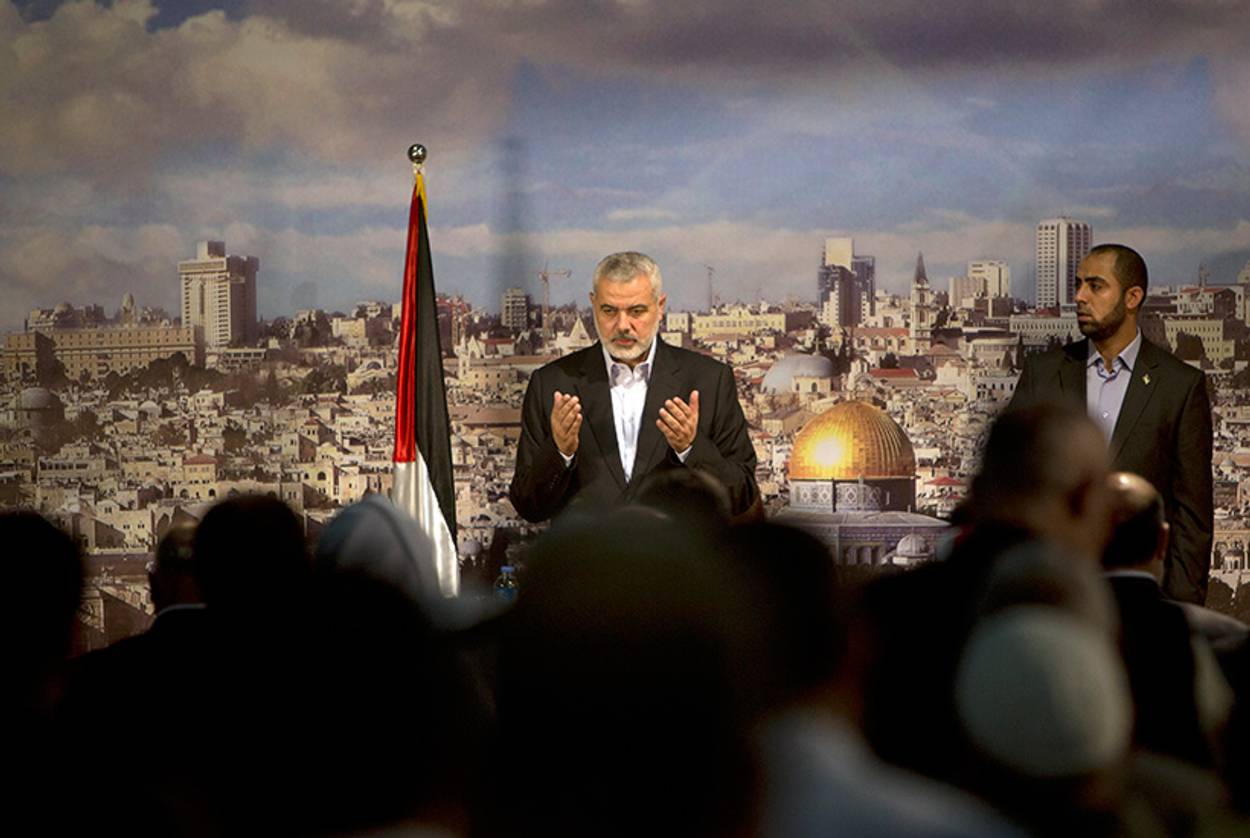

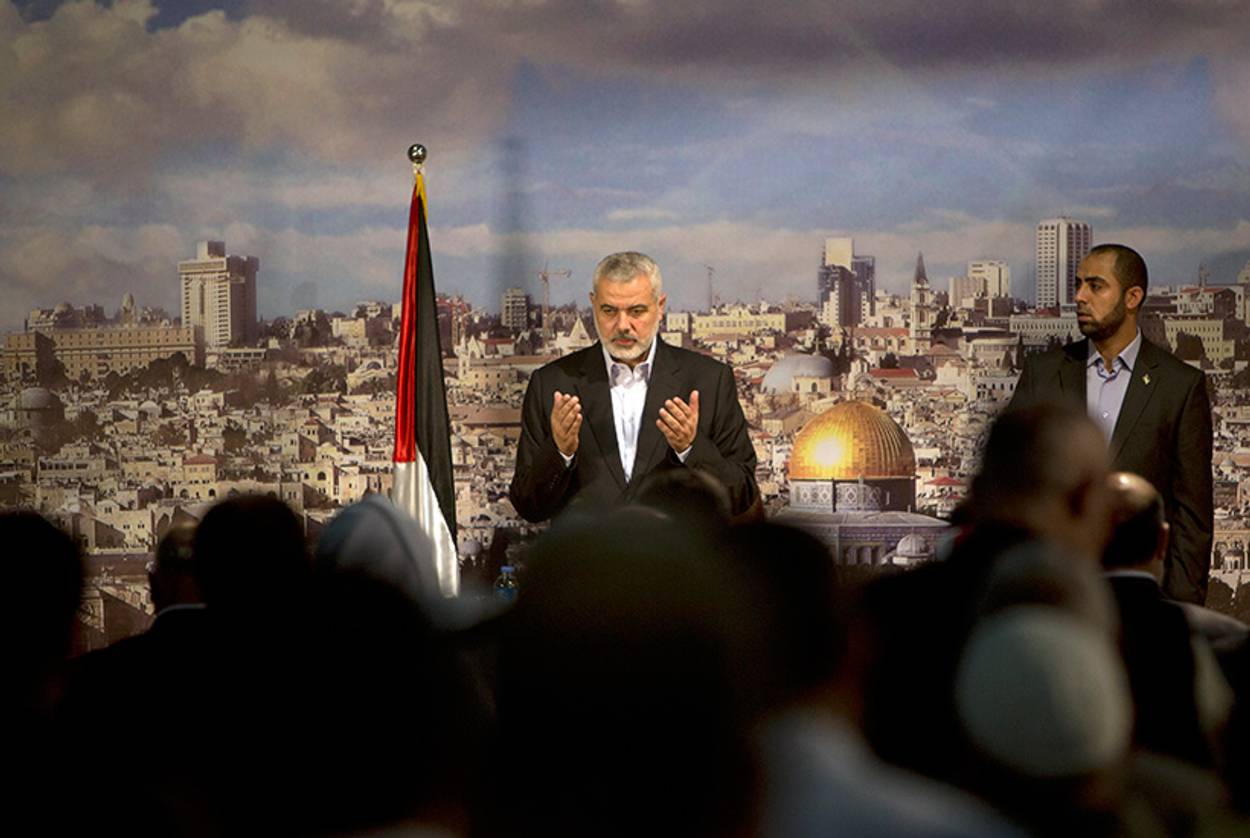

The first, and biggest, hit to Hamas has been the outbreak and steady escalation of the civil war in Syria. Hamas, a Sunni Islamist organization, has long maintained a system of mutually beneficial regional alliances with the Alawite regime of the Assad family and its Shi’ite Iranian backers in Tehran. But as the tenor of the battle in Syria turned increasingly sectarian, Hamas chose to side with the predominantly Sunni Syrian opposition and expressed support for other Arab revolutions. “I salute all people of the Arab Spring,” Ismail Haniya, Hamas’ prime minister in Gaza, said last year.

In early 2012, Hamas leadership left its longtime base in Damascus and established a new foothold in Cairo—a move that prompted Iran to drastically reduce its funding to the group. The subsequent victory by the ideologically sympathetic Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt’s elections in the summer of 2012 helped cushion the blow of the break with Tehran, but that partnership came to a swift end this July, after the Muslim Brotherhood President Mohammed Morsi was ousted by military takeover in Cairo. Under the leadership of Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the military government in Egypt has embarked on a brutal campaign to destroy smuggling tunnels into Gaza and further isolate Hamas as part of an overall campaign against the Muslim Brotherhood and other jihadist groups. The Egyptian military claims to have destroyed 800 tunnels this year—at an estimated cost to Hamas of $230 million per month, according to Hatem Oweida, the group’s deputy minister for the economy.

In recent months, Hamas has turned back to Tehran in hopes of repairing the relationship. In September, As-Safir, a pro-Hezbollah Lebanese daily, reported that Iran had resumed funding to the organization—largesse that came at the cost of official backtracking by Hamas with regard to its position on the war in Syria, which has now been revised to express a desire to see only “peaceful means” used in the uprising. However, Tehran—unwilling to risk an international incident that could jeopardize its efforts to win sanctions relief from the West—postponed a planned visit by Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal in October. Iran’s resumption of funding to Hamas has been so limited it looks more like a half-hearted attempt to keep the channel open than any sort of legitimate desire for the resumption of a strong alliance between Tehran and Hamas, but Hamas lacks any leverage with Iran right now and will be forced to take what it can get.

Hamas still maintains positive relations with both Turkey and Qatar, but neither country is interested in being a primary sponsor of the Islamist government in Gaza. Turkey’s relationship with Israel remains tense, and three years after the disastrous Mavi Marmara raid, Jerusalem continues to block Turkish access to Gaza, a position shared by Egypt’s military authorities, who in August refused Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan entrance to Gaza, as retaliation for Turkey’s support of Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood. Meanwhile, Qatar’s new leaders have chosen to make the Syrian opposition their top priority—not least because Qatar’s emir knows that support for Hamas presents image problems in the West, leaving the group with only a fair-weather friend in Doha, at best.

As bad as the external situation is, the internal situation for Hamas is not much better. The organization has no real claim to democratic rule in Gaza, despite winning electoral victory in 2006; those elections were, of course, followed by a bloody civil war with Fatah, and the unresolved split with the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority government in Ramallah has resulted in the continuing failure to hold any subsequent votes. Recent polling data by An-Najah University indicated that only 12.1 percent of Palestinians would vote for Hamas, compared to 35.6 percent for Fatah.

***

It would seem, then, that the time is right for a challenge to Hamas rule. This autumn, a new organization, Tamarod Gaza—named after the Tamarod movement in Egypt, which helped overthrow Mohammed Morsi this past summer—emerged, hoping to capitalize on general public discontent with Hamas rule. The group promised to bring a million Gazans out on Nov. 11 for a mass protest—a Palestinian Spring. But in the event, Tamarod Gaza never actually showed up: The group was forced to cancel the protest, likely due to a large-scale crackdown by Hamas, and November passed quietly. Tamarod Gaza attempted to save face by taking credit for the quiet on Gaza’s streets: “Tamarod has imposed its control over Gaza,” read a statement the group posted on Facebook.

But despite being bound by a series of poor circumstances, Hamas nevertheless remains in a temporarily stable position, in possession of sufficient strength to stay in power in Gaza and intimidate internal dissent such as Tamarod Gaza, while lacking the funds, allies, or resources to be much of a threat to anyone other than the people of Gaza. A year after Israel’s brief Pillar of Defense operation, the most news Hamas has recently made was the discovery in October of a tunnel from Gaza into Israel.

The organization has a penchant for resilience and a knack for biding its time. If anything, the upheaval in the Middle East shows just how quickly luck can turn around. While “wait and see” rarely makes for good policy, neither Hamas nor its foes seem to have much of a strategy for moving forward.

Those hoping that Hamas’ relative weakness might bring about a bold move such as recognizing Israel are likely to be disappointed. Though desperate, Hamas relies on resistance to Israel as its raison d’être. With American-brokered peace talks officially ongoing between the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority and Israel, Hamas must preserve its traditional role in the opposition to save face in Palestinian society. This is especially true given the emergence of Salafist organizations that have provided a challenge from the right, giving Meshaal a pressing internal incentive to derail any moves toward peace with a new round of rocket attacks.

And while Hamas may find itself boxed in by its alliance with Iran—which may wish to burnish its credentials as a good-faith player by reining in its junior partner—it could equally find its value to Tehran skyrocketing if the nuclear talks fall apart, as Iran seeks to quickly expand its influence and present a credible threat of counterattack to any Israeli attack on Iranian nuclear facilities.

Nevertheless, Israel is currently preoccupied with matters other than toppling the Islamist government in Gaza. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu remains committed to focusing first on Iran’s nuclear program and expending whatever remaining energy and political leverage he has on the Syrian situation and the ongoing negotiations with the Palestinian Authority.

The past year has seen Hamas move decidedly into the “Arab Spring” loser column without any significant action by either Jerusalem or Washington, but Hamas will undoubtedly seek ways to keep itself relevant, whether by undermining peace talks, or acting as a proxy for Iran. Unfortunately, the failure of Tamarod Gaza has dampened the prospect of an internal revolution and overthrow of Hamas, at least in the near future. Israel, and the United States, cannot afford to wait for Hamas to turn its fortunes around.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Josh Nason recently received his master’s degree in Middle East Studies at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

Josh Nason recently received his master’s degree in Middle East Studies at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.