In Plain Sight

The recent arrest of Pakistani nationals in the aftermath of Bin Laden’s death reveals that the operation was the result of internal Middle East politics—and no coup for U.S. spycraft

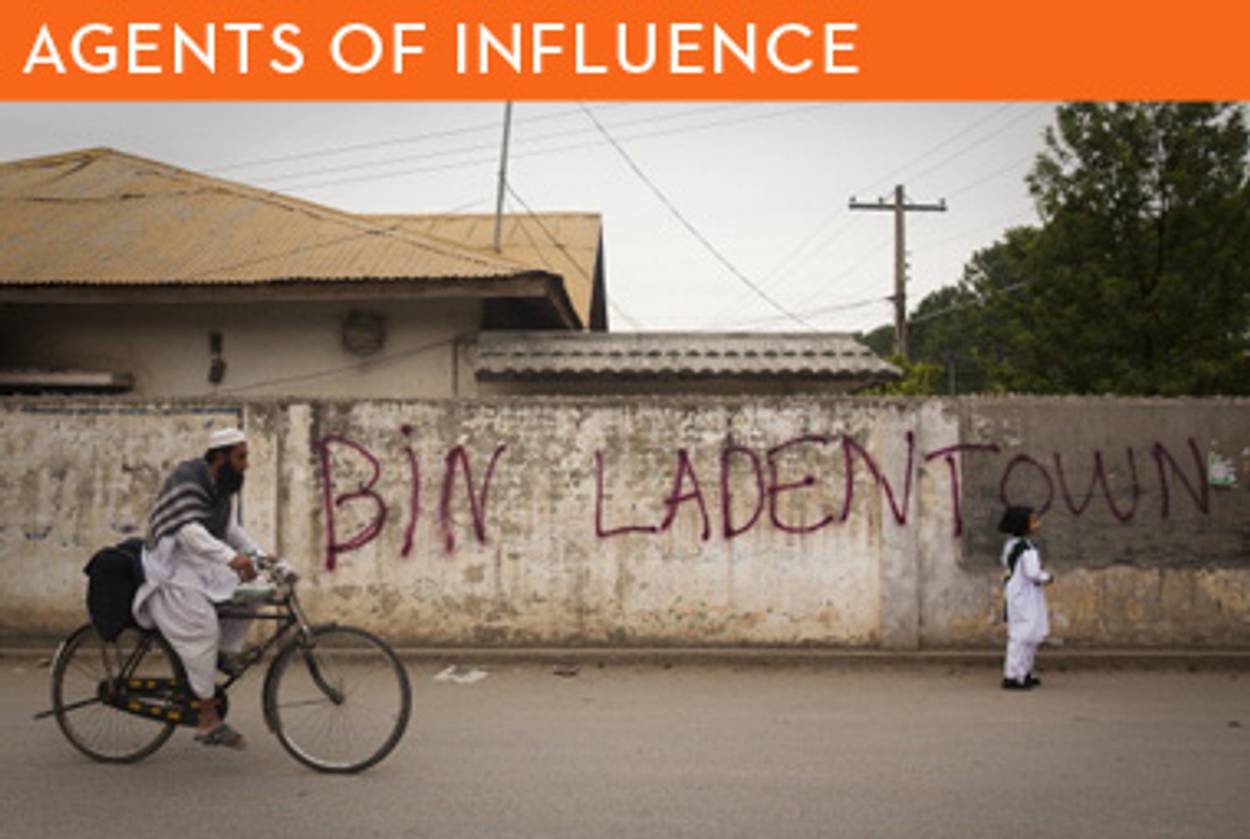

For five years, Osama Bin Laden lived in the Pakistani equivalent of West Point. He was not hiding, as many have presented it; he was being hidden. But by whom?

Well, by the kind of people who might feel comfortable custom-building a compound 100 meters from Pakistan’s leading military college to house the world’s most wanted terrorist.

It is no surprise that the recent arrests by the Pakistani government of several of its citizens for allegedly helping the CIA hunt Bin Laden is being reported as yet another sign of a growing divide between Washington and Islamabad. The New York Times reported the story straight, quoting the head of the House Intelligence Committee, Michigan Republican Rep. Mike Rogers, who accused elements of the ISI and the military of protecting Bin Laden, a fact that you probably don’t need classified access to figure out.

Yet the congressman’s understanding reflects—as does the Times story—America’s broader problem in understanding and engaging with our enemies and allies alike. The significance of the arrests is not that they show that the Pakistani military protected Bin Laden: It shows that elements of Pakistan’s military or its intelligence service, the ISI, were also responsible for Bin Laden’s death.

Until yesterday’s revelation of the arrests there was no indication that Washington had any Pakistani assistance at all in finding and killing the al-Qaida chief. The story was that U.S. intelligence had located public enemy No. 1 by tracking one of Bin Laden’s loose-lipped couriers to the Abbottabad compound. The Americans, the story goes, never said a thing to the Pakistanis for fear that it would wreck the operation. And so the United States relied on satellite surveillance until the day the president gave the go-ahead to the SEAL team that finished the job.

Presumably, the Pakistanis recognized immediately that the story the Americans were peddling was nonsense. Someone in Pakistan—in either the military-security apparatus or from the political echelons—had to have sold Bin Laden to the Americans. I think it’s safe to assume that, for the last month and a half, Pakistani officials have been working to find out who bartered their prize away—and what they got in return.

It is possible that some Pakistani police and counterintelligence officials investigating the operation are motivated by sentimental or ideological reasons: They liked and sympathized with Bin Laden. Others realized that for all the noise about the refuge and killing of Bin Laden in Pakistan being an embarrassment to the army and ISI, this was a choice opportunity to stick it to the Americans, again, and make some money in the bargain. The five CIA informants that the Pakistanis have so far arrested—including an army major and the contractor who built Bin Laden’s house—are little fish that the Pakistanis are dangling to see what the Americans will do, or pay, to protect the key Pakistani assets who gave them their orders.

Even more interesting is the American version of the story, which is helpful mainly insofar as it illuminates the current U.S. position after 10 years of war in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The American public wants to believe in a simple, heroic story of Bin Laden’s killing, if only to celebrate the hard work of our intelligence community and special operators like the SEALs. But let’s remember that for all the excellent work the CIA does—and we are right to keep in mind that the agency’s successes are secret while its failures are public—America’s intelligence record is mixed.

In the winter of 2009, the CIA was tragically caught off guard when an asset of Jordanian intelligence turned out to be a double agent: He walked into a U.S. compound in Afghanistan and killed seven agency officers in a suicide operation. The problem was not that there were seven officers all in one place, but that U.S. counterintelligence had no idea that their prize was working for al-Qaida. Faulty counterintelligence is part of the agency’s Cold War legacy, according to which some of the walk-ins, or people who voluntarily came forward to provide us with information, were apparently Soviet assets. It seems they were simply providing false information—which, when combined with good information, made it difficult to detect that they were still controlled by our adversary. The United States was incapable of knowing what was true and what was false. Some speculate that this Cold War conundrum drove James Jesus Angleton, the CIA’s legendary head of counterintelligence, to paranoia. By the end of the Cold War, one of the CIA’s leading counterintelligence officers, Aldrich Ames, was revealed to be a double agent who betrayed nearly every one of the CIA’s assets in the Soviet Union (damage that appears to have initially been blamed on Jonathan Pollard).

Of course, it’s not easy to do good counterintelligence work. Some compare it to an elaborate game of three-dimensional chess. While the analogy seems suitable enough for a middle-class American sensibility that perceives of chess as something daunting, serious, and foreign, it is truly not foreign enough by half. Good counterintelligence requires a type of mind most likely found in this country running a California drug gang. The U.S. intelligence community does not actively recruit such sociopaths into its ranks, so in the end it is often ineffective at doing counterintelligence work in countries that are run by sociopaths.

For example, Leon Panetta, a very skilled political operator with many years of experience in Washington bureaucracies, has no idea what it takes to become chief of staff of the Pakistani army, like Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, and to hold onto that position among so many murderous rivals—like the junior officers who want to oust him for his cozy relationship with Washington. Our inability to actually think like the people we are trying to influence or defeat is ultimately a much more fundamental problem than the challenges of securing Pakistan’s nuclear weapons. Both our adversaries and our allies in the Middle East—the political and military leadership of countries like Syria and Iran and Iraq and Egypt alike—are the products of a kind of finishing school that makes Rikers Island look like Miss Porter’s prep school. What they had to do to secure power and then maintain it is beyond the imagination of any U.S. official who thinks Rahm Emanuel is a tough guy or that the West Wing of the White House is a snake pit or is stung by a slighting mention by Bob Woodward.

So, who are these people? Bashar al-Assad, for instance, has astonished the international community with his slaughter of unarmed civilians because the leaders of the Western democracies are incapable of imagining a “Westernized” ophthalmologist being capable of such violence. His Arab peers know better, which is why they are saying nothing; they’re scared of him, because he is a sociopath who tortures, maims, and kills children without blinking. NATO thought Muammar Qaddafi was a lunatic in funny robes who would fold at the first—or fifth—aerial bombardment of Tripoli. What they missed was the fact that Qaddafi is the kind of funny lunatic who held onto power for four decades while gleefully slaughtering his political opponents, manipulating Libya’s tribes, and stashing billions of dollars away for exactly the moment when the West would try to drive him from power, and who pays African mercenaries a thousand dollars a day to rape his own people.

And so we wonder why things go wrong when we try to engage the Syrians and Iranians, or to get the Pakistanis to choose a side (our side). The fact is that we don’t see the world the way they do.

But thank God for that. We want the American story about Bin Laden’s courier and the heroic SEAL team—a story that is obviously incomplete—to be true because we prize transparency, a workable chronology, understandable motives, and clear loyalties. But the American story will never be true in Pakistan or in the Middle East. Washington likes to pretend it is fighting a regular war against an enemy we can capture or kill, like Bin Laden. But it’s not. It is fighting a war where the United States cannot come down too heavily on Pakistan, even when it harbors mass murderers of Americans, because it needs Pakistan in order to fight in Afghanistan, against insurgents backed by elements of Pakistan’s military-security establishment, who might in turn gain access to Islamabad’s nuclear arsenal. Does that make sense? Not to us. Indeed, as far as the Pakistanis are concerned, the Americans are simply tourists in Afghanistan, albeit well-paying ones. But this is precisely the kind of conflict the Pakistanis are accustomed to.

Keep in mind what Afghanistan is to the Pakistanis: part of their war with India. Because Pakistan fears an invasion by its archrival, it needs strategic depth in Afghanistan where it can regroup in the event it is overwhelmed by the superior Indian forces in the early days of a prospective war. It is to that end that the Pakistanis have cultivated alliances with Afghani insurgent groups allied with al-Qaida. When the Pakistanis refuse to help us in Afghanistan, it is not because they are fighting us, but because they are preparing for war with India.

There is also a second conflict under way in Pakistan: the de facto war for control of the Pakistani state between various cliques of the country’s political and military leadership. Remember that when American officials describe support for al-Qaida and the Taliban coming from elements of the Pakistani security and military establishment, that means there are other elements, too—those with whom the pro-insurgent figures are at war.

America has little to do with either the Pakistan-India conflict or the Pakistani-Pakistani clash. To some Pakistani officials we are a nuisance, and to others we offer them a means by which to fight their internal rivals. That’s why Bin Laden was sold to the Americans by one side. Now it’s time for the other side to get their piece of the pie.

The real question Washington ought to be asking is: After five years of being hidden by elements of the Pakistani state, why was Bin Laden given up now?

Lee Smith is the author of The Consequences of Syria.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).