The iNakba, a New Political App, Is a Terrible Idea

Available next week on your iPhone, it only deepens the divide between Israelis and Palestinians over the meaning of land

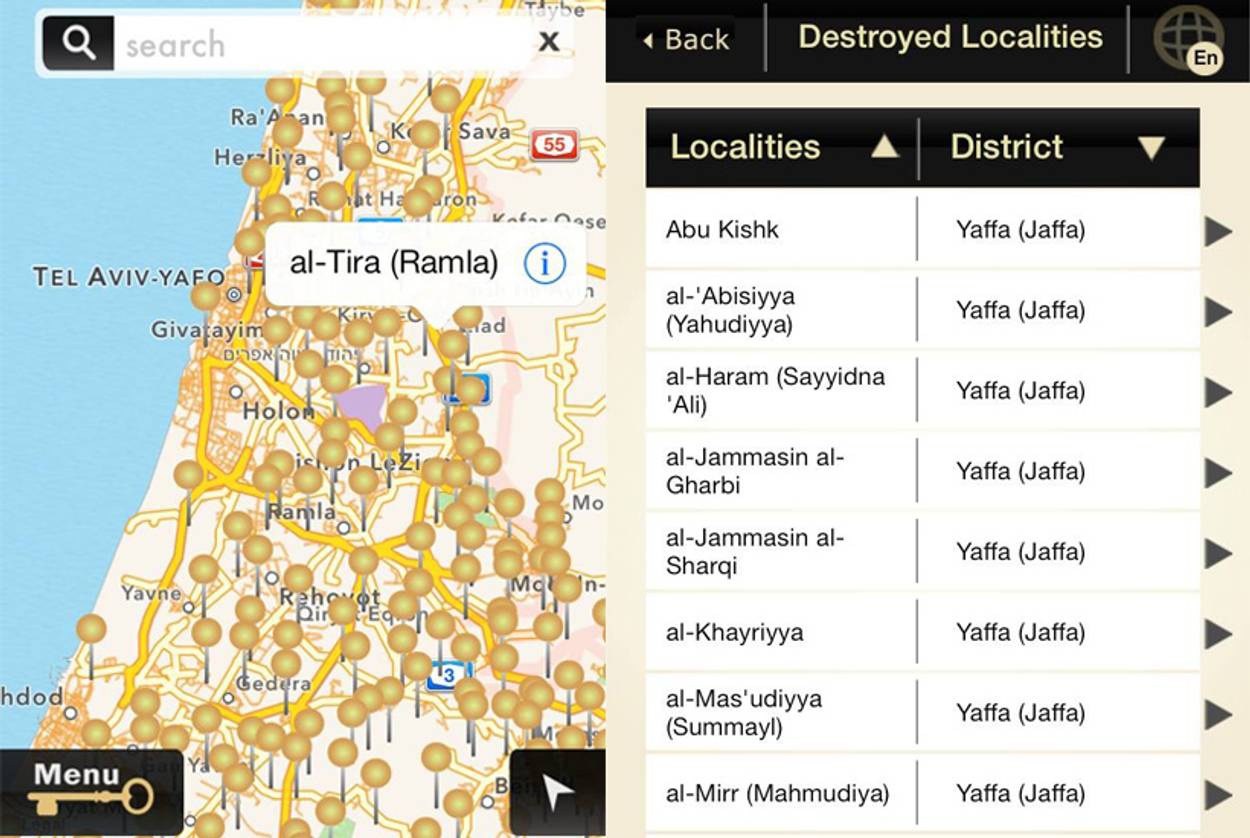

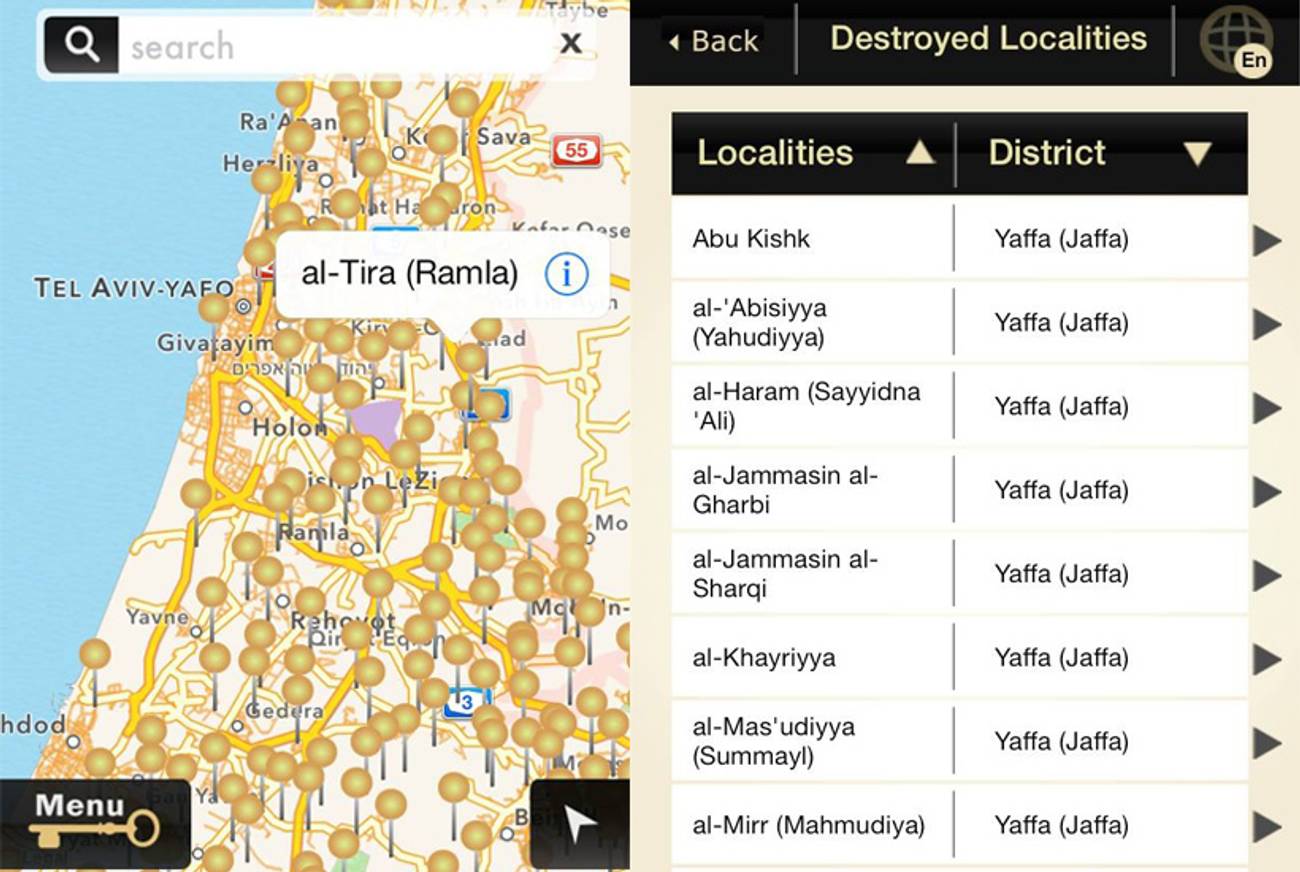

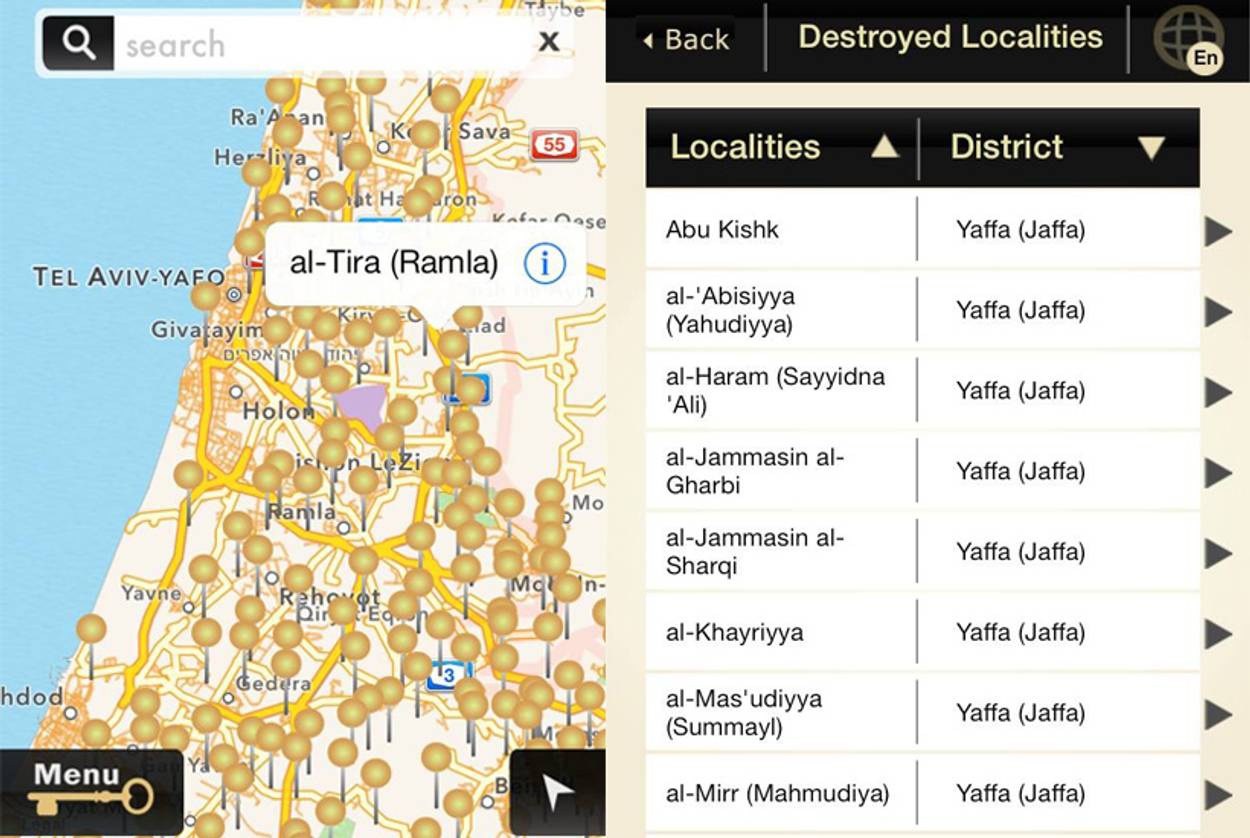

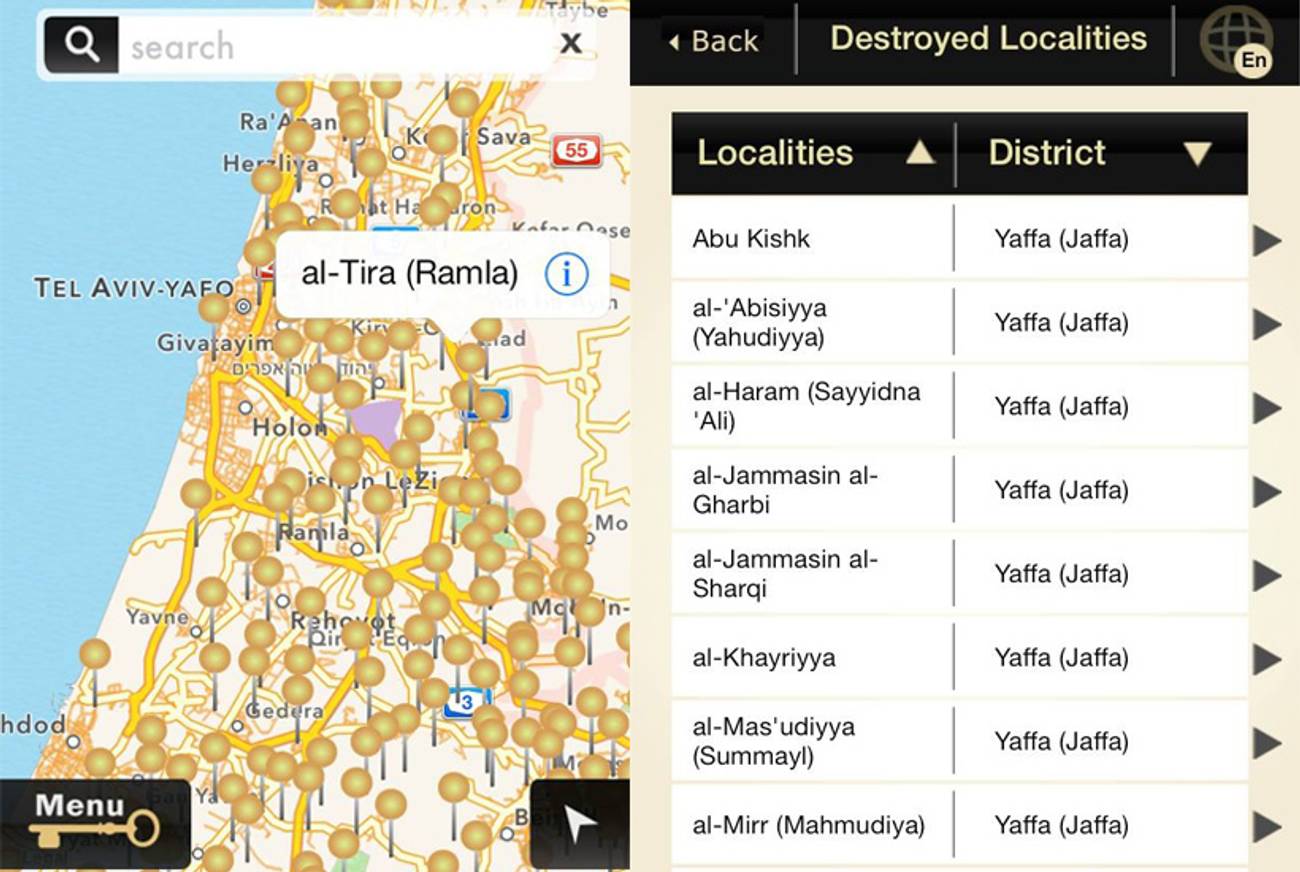

Now that Flappy Bird is no longer with us, many of you may be looking for another iPhone app that’s thorny, puzzling, and ultimately exasperating. Well, look no further: Next week, the radical left-wing Israeli nonprofit group Zochrot will launch the iNakba, a slickly designed application based on the Google Maps interface that will take users on virtual tours of the Arab villages abandoned in 1948, in what Israelis call the War of Independence and Arabs refer to as the Nakba, or the catastrophe. Not surprisingly for an app commemorating a collective trauma, the iNakba will enable users to share their photographs and accounts of life before the ascent of the Jewish state.

It’s easy to dismiss the app as a gimmick—the name itself begs it. It’s easier still to argue, correctly, that reducing any cataclysmic event to dots on a map is trivializing, and that an app, for all of its cool factor, is hardly the most suitable canvas on which to paint a historical picture that is infinitely complex. These are all worthy conversations to have, and, with some luck, once the din of controversy dies down, the iNakba will inspire a pleasant debate about the intersections of technology, memory, and nationality.

For now, however, the app has a more pressing calling: It reminds us what we too often forget, namely that Israelis and Palestinians aren’t merely locked in a fight over a narrow strip of land but engaged in a wider and more complicated discussion of what land means.

This isn’t a mere intellectual debate. As Todd Gitlin and I argued in a book about the idea of the chosen people, the first Zionists returning to the land of Israel en masse after millennia in exile soon realized that they and their new Arab neighbors were separated not only by religion but also by ontology. For the Jews, the land was an abstract notion twice over, first because it was a commodity that they could convince its owners, many of whom were absentee landlords, to sell, and then again because no piece of the land of Israel was ever just a wadi or a dune or a meadow: For the Zionists, even the fiercely secular among them, every wadi still echoed with King David’s song, and each dune was still fresh with Solomon’s footprints.

The land, then, was, first and foremost, an idea, rooted in the ancient narrative of divine promise and national rebirth. As such, it had to be not just cultivated but worshipped. It’s not for nothing that A.D. Gordon, the leading light of Labor Zionism, spoke of “the religion of work” and insisted that the hoe and the till were the tools that would permit the Jews a mystical reentry into history, once again an independent nation like all others, proud and safe in its natural homeland.

Far from marginal or extreme, the same worldview, more or less, was espoused by Herzl himself. In his 1902 utopian novel Alteneuland, Zionism’s founding father had one character explain the belief that young Jews emigrating to Palestine will succeed as farmers where generations of seasoned Arab laborers had failed and will make the desert bloom. “The sacred soil,” thunders Herzl’s young Zionist, “was unproductive for others, but for us it was a good soil. Because we fertilized it with our love.”

The Arabs were not as … romantic. Their claim on the land was rooted in continuous habitation of specific homes, in ongoing cultivation of particular fields. In their eyes, hundreds of years of residence on the same hilltop trumped both ownership deeds and ideological sentiments: A person could claim a piece of land only if he or she could trace three, four, 10 generations back to the same swath of earth.

In one of his best-known poems, Mahmoud Darwish, the most celebrated of all Palestinian poets, made this argument provocatively by writing in the voice of a young Israeli soldier. The poem was published in 1967, shortly after Israel won the Six Day War, tripled its size, and succumbed to a wave of patriotic and religious euphoria; in Darwish’s verse, the Israeli soldier is open about his ambivalence toward the land he’d just helped seize. “I don’t know it,” he says, “& I don’t feel it as skin & heartbeat.” He goes on: “Let me tell you what keeps me in this place:/ the speeches stirred me up/ they taught me to love the idea of love/ but I didn’t share the land’s heart./ The smell of grass/ putting down roots/ branches …/ that part’s a dream it’s not real.”

The iNakba adheres to the same logic. It’s all about roots and branches, however virtual. It is not interested in sweeping themes and movements of armies and causes and consequences; its focus are the homes and the yards and the smell of the grass of individual places long gone.

And this is precisely why it’s so unhelpful. The real tragic nature of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, what sets it apart and makes it so fascinating to so many people who otherwise have no allegiance to one side or another, isn’t just its sheer volume of years and casualties; it’s the collision of two unbridgeable yet equally valid narratives. The Arabs who live in Israel and east of the Green Line are correct to point out their concrete connection to the land and to bemoan the circumstances that drove them out of abodes they had occupied for centuries. The Israelis are just as correct to state their undeniable claim on the very same land, a claim based on historical presence, spiritual affiliation, and legal repatriation in the 19th and 20th centuries. And just as most Palestinians, most likely, haven’t forgotten the villages that dot the map of the iNakba, most Israelis still remember Hebron, which is of tremendous historical and religious significance and where Jews had lived and prayed from the days of Abraham on.

And yet, in any future peace treaty, should one ever materialize, the current Jewish community in Hebron would have to be uprooted. Most Israelis, as poll after poll shows, accept that as a painful but necessary condition of ending the conflict. Rather than hold on to the maps of the past, in their hearts or on their iPhone screens, Palestinians and their supporters ought to do the same.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.