The festive signing of the Oslo Peace Accords in September 1993 found Husam Badran, a founding member of Hamas and later a director of the organization’s military wing, in Israel’s high security Nafha Prison, serving time for terror activities. His fellow security prisoners—jubilantly following the ceremony on TV—started packing their bags, expecting to be released imminently in a mass amnesty. But Badran kept his cool.

“After all they’d suffered, they felt this was real. But I told them: ‘Don’t be in such a rush. We will be freed after serving our full sentences, then we will be arrested again and again as negotiations proceed.’ And that is indeed what happened.”

Twenty-five years later, the senior Hamas leader, who was convicted of overseeing some of the most infamous bombings by the terror group, including the 2001 bombing of the Sbarro Pizza in Jerusalem which killed 15 Israeli civilians, and the bombing of the Dolphinarium Discotheque in Tel Aviv, which killed 21, feels that he has been vindicated. With President Donald Trump delivering blow after political blow to Badran’s avowed adversary Mahmoud Abbas—first cutting funds to the Palestinian Authority, then moving the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem, and now shuttering the PLO offices in Washington, D.C.—Badran is confident that he can convince his people that the now-defunct peace process was a sham all along.

“We always knew that Oslo was an illusion. Today we’ve been proven right: Oslo never bred a Palestinian State nor retrieved the rights of the Palestinian people.” These days, he added, “not one person will defend Oslo on official Palestinian TV.”

It is rare for a Hamas official to grant an extensive interview to a Jewish media outlet. But these are unusual times. My contact with Badran came through the connections of Rabbi Michael Melchior, a peace activist and former minister in Ehud Barak’s government, with members of the Islamic movement in Israel and abroad. In a two-hour interview held in a restaurant in Istanbul, and conducted in Arabic peppered with Hebrew, Badran expounded on his worldview: Yes to realistic, ad hoc understandings with Israel, no to final status agreements the likes of the Oslo Accords. He took pains to present his movement’s position as pragmatic, not dogmatic or messianic. He suggests that his organization’s beliefs are not unlike those of the ideological right in Israel.

“The entire Israeli right believes in the whole Land of Israel and we believe that all of Palestine is historically ours,” Badran explains. “But having recognized reality and the changing international situation, we’ve agreed to a Palestinian state on a part of the territory which the entire world considers occupied.”

Hamas’ top political echelon—Badran among them—is currently engaged in indirect talks with Israel in Cairo to renew the 2014 ceasefire, which both sides largely observed up until the recent flareup this summer. “If the Israelis knew the conditions for a ceasefire, they would be out on the streets protesting against the government for its hesitation,” he asserts. “We offer Israelis a ceasefire for an agreed upon time frame. They will no longer hear red alerts. No longer suffer field fires. For that, the price they would need to pay would be nothing.”

“Nothing,” according to Badran, means the permanent opening of border crossings with Gaza to people and goods. This, he explained, would alleviate the plight of the Strip’s 2 million residents, who suffer from 80 percent unemployment with rampant sickness and hunger. While Hamas continues to demand the construction of a sea port and an airport, Badran says those infrastructures are secondary to the daily needs of ordinary Gazans.

“It will take three years to construct a port. A year to rebuild the airport. But the average Palestinian doesn’t need an airplane to fly in, he needs an airplane not to bomb him. He needs medical treatment, he needs food.”

The reason for the deadlock in solving the Gaza crisis is twofold, Badran explained: Fatah’s obstructionism and Israel’s flawed decision making. Over the past two years, Mahmoud Abbas’ Palestinian Authority has upped its ante in a bid to force Hamas to hand over security control in the Gaza Strip. It has refused to pay Gaza’s electric bill to the Israel Electric Corporation; discontinued medical transfers of patients out of the Gaza Strip and shipments of medicine into it; and slashed salaries to tens of thousands of civil servants in the Hamas-held enclave. Badran also argues that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s competition with political rivals on the right ahead of the upcoming elections has prevented him from taking bold moves to end the Gaza conflict.

“Israel has a problem with decision making,” he said. “Many decisions are taken for reasons of political expediency, and it’s only getting worse. In the past, the army and the Shin Bet would call the shots. Today, it’s the politicians acting out of personal motivations, which actually makes me happy because it proves that Israeli institutions are weakening.”

Israel began talks in Cairo with a demand that Hamas stop the development and export of weapons, Badran said, a gambit that Hamas replied to with contempt. “If Israel wants to talk about weapons, I could bring up the issue of return to Lod and Jerusalem, which makes no sense,” he explained. “All we want is to return to the 2014 ceasefire deal. We don’t want a political agreement, and Netanyahu has no interest in one either.”

The main sticking point in the negotiations, which Israel does not acknowledge as such, seems to be Israeli insistence that as part of any deal Hamas release Avera Mengistu and Hisham el-Sayed, two mentally unstable civilians who entered Gaza, and return the bodies of IDF soldiers Oron Shaul and Hadar Goldin, who were killed in action during Operation Protective Edge. Hamas is adamant that a prisoner swap be negotiated separately from the ceasefire agreement.

“The prisoner issue is separate. No one dreams that the siege on Gaza will be removed in return for the release of [Israeli] prisoners. Even the hungry Gazans will reject such a notion,” Badran asserted. Following Operation Protective Edge in 2014, Israel offered Hamas a prisoner swap through which the Israelis held in Gaza would be traded for 19 bodies and 18 live Hamas operatives captured in battle. Hamas rejected the Israeli offer out of hand. Badran said that his movement now insists on a new prisoner swap “no less significant than the Gilad Shalit deal,” in which the Netanyahu government in 2011 traded an Israeli corporal for 1,027 Palestinian prisoners, including Badran himself. The new deal, he said, must stipulate the release of the remaining 26 veteran security prisoners sentenced before the signing of the Oslo Accords. The swap must also include over 40 Hamas members who had been released by Israel in the Shalit deal but were rearrested following the abduction of three Israeli teenagers in the Etzion Bloc in 2014.

“By re-arresting them and reinstating their original prison sentences, Israel violated the conditions of the Shalit deal,” Badran argued. “We won’t be sold the same merchandise twice.”

While refusing to divulge any information on the wellbeing of the Israelis held in Gaza, the official argued that Hamas’ treatment of Gilad Shalit during his five years in captivity proved his movement’s humane treatment of Israeli captives.

“The Israelis tried to say that Shalit was held underground, but we released footage of him eating meat on the Gaza beach,” Badran said. “We knew it was risky, we knew Israel was monitoring us, but we are human beings. A person can’t be held in hiding for five years.”

“Our experience in the Shalit deal was successful, and the upcoming deal will be even more so,” he summarized.

For Badran, the Shalit deal was a great personal triumph. It cut in half his 18-year prison term for involvement in a series of deadly suicide attacks that left 120 Israelis dead during the Second Intifada, attacks he was convicted of masterminding in 2002 as head of Hamas’ militant al-Qassam Brigades in the northern West Bank.

“I was investigated for almost a year in total, but never spoke or confessed to anything,” he told me. After the investigation was over, I received more honor from my investigators than did the prisoners who confessed. That, he said, taught him that “those who give their services to Israel are only humiliated for it.”

Born and raised in Nablus’ Askar refugee camp—a neighborhood so crowded that “when my neighbor and I would watch the same TV channel, I would mute the sound”—Badran majored in history at An-Najah University, worked as a schoolteacher, and never thought he would become a militant. Growing up, he said, he was calm and never fought with other kids on the street.

But in late 1987, at the tender age of 21, Badran became one of the founding members of Hamas. Established as the Palestinian branch of the global Muslim Brotherhood—its symbol two swords on the backdrop of Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock—Hamas was created to thwart the first signs of normalization between the PLO and Israel. Almost immediately, Badran was appointed head of Hamas’ al-Qassam Brigades in the northern West Bank, a position he held until his arrest in April 2002, which followed a protracted standoff with an Israeli attack helicopter firing rounds at his hideout. The arrest was his fifth. By the time he was released from jail in October 2011 and promptly deported to Qatar as part of the prisoner swap, he had spent a total of 14 years behind Israeli bars. In jail, Badran taught himself Hebrew and was elected as representative of hundreds of Hamas prisoners to Israeli authorities.

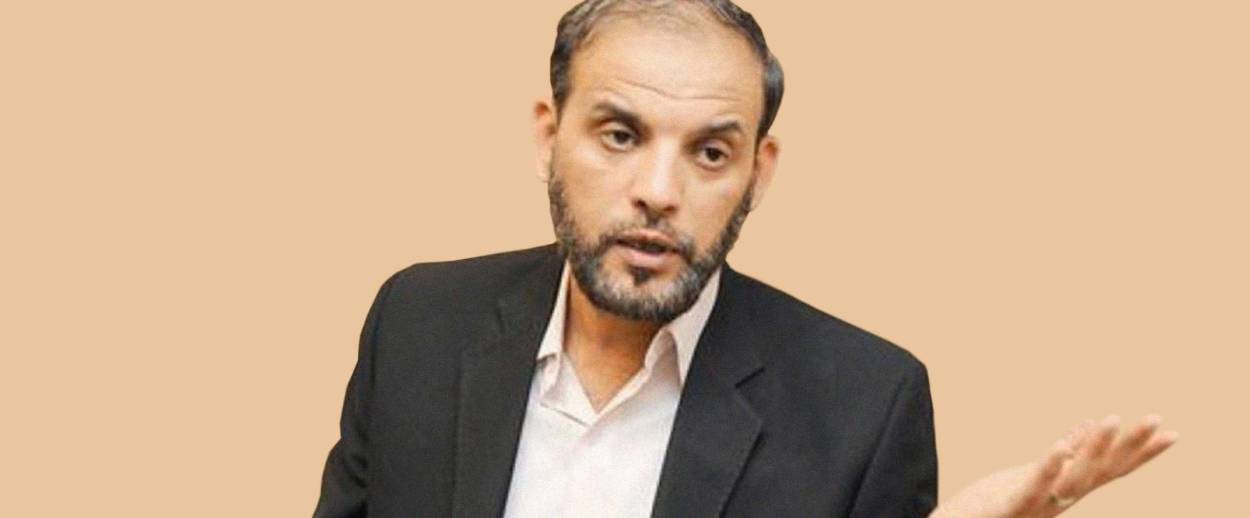

Today, at 52, Badran is a rising star in Hamas’ political leadership. After serving as his movement’s spokesman, in May 2017 he was elected to the Political Bureau, the 19-member governing body of the Islamic movement. He holds the significant National Relations portfolio, tasked with liaising between his movement and other Palestinian factions, as well as with Palestinian civil society.

While congratulating his rival Abbas for seemingly abandoning the negotiations track and focusing on diplomatic warfare against Israel, Badran nevertheless believes that terror—in his parlance, armed struggle—must remain part of his organization’s toolbox. He remains unfazed by the fact that over a decade since it took control of the Gaza Strip, Hamas is still classified as a terror group by the United States and the European Union. “The world only respects the powerful,” he recently wrote on Facebook. “Our strength as Palestinians lies firstly in our unity and secondly in holding on to the weapons of resistance.”

Unlike Mahmoud Abbas—who dubbed the Second Intifada a disaster for the Palestinian cause and helped Israel quash it—Badran sees no contradiction between diplomatic action against Israel in international forums and armed attacks against Israelis in the West Bank.

“Israel has proven both to the world and to the Palestinians that you can receive no rights through negotiations or goodwill alone,” he said. “But armed resistance alone won’t suffice either.” He is convinced that the world will accept his two-pronged approached to national liberation, just as in states “there is no contradiction between a foreign ministry and a defense ministry.”

“In the Vietnam War, the Americans negotiated with groups that were actively fighting them,” Badran told me. “They are doing so today with the Taliban in Afghanistan, which are ideologically more stringent than us, and the world accepts it. The French occupation in Algeria lasted for 130 years, ending with negotiations in Paris while fighting continued in Algeria.”

In recent months, Hamas has used limited violence to force Israel back to the 2014 ceasefire agreement, though Badran insisted that weekly protests along the border fence—coupled with the launching of flammable balloons and kites that have burned over 1,200 acres of Israeli fields—are spontaneous expressions of popular frustration rather than a media extravaganza orchestrated by Hamas. “People in such a desperate situation don’t need encouragement to go out and protest,” he insisted. However, he did concede that over the Muslim Festival of Sacrifice (Eid al-Adha) in late August, it was Hamas that reduced the “spontaneous” demonstration and launching of balloons “to zero.” The arson attacks resumed, he said, “because the Israeli minds are closed.”

In June, the IDF spokesman released footage proving that Hamas was indeed behind the cross-border arson attacks. While admitting that Hamas controls the level of flames on the border, Badran directed a tacit threat at Israeli decision makers.

“The situation on the border can erupt at any moment. Anger is mounting, and every day that goes by can be the fuse that causes the explosion. If such an explosion does occur, all previous rounds will look like an experiment. Gaza will suffer, surely, but so will Israel.”

Though Badran won’t admit it, Hamas has returned to the negotiating table with Israel out of a position of weakness. Its income dramatically reduced by the destruction of smuggling tunnels on the Egyptian border, its regional alliances also suffered a blow with the end of Mohammed Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood regime in Egypt in 2013. Yet things have started looking brighter for Hamas on the diplomatic front. Though the movement never renewed its ties with the Assad regime since abandoning its Damascus headquarters in January 2012, relations with Iran have witnessed a steady improvement and are now “very good,” Badran said, and “back to where they were before we left Syria.” Hamas leaders have also been granted license to renew their permanent presence in Cairo.

While Badran acknowledges that the economic situation in Gaza is far worse than that of the West Bank, he insists that “at least people in Gaza have their self-dignity. There is nothing worse than occupation,” he continued. “The level of humiliation in the West Bank is unprecedented. It is easier to live poor and free than rich and under occupation. At least in Gaza Palestinians sleep tight knowing that no Israeli [soldier] will come knocking at their door.”

Badran now divides his time between Doha, Istanbul, and Beirut. Asked if he regretted anything in his past, he was adamantly negative. “I would do nothing different,” he said.

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.