How the State of Israel Abuses Holocaust Survivors

With millions of dollars earmarked for their care, how is it possible that even in Israel some Shoah victims are living and dying with indignity?

On a warm, sunny day in March, Rosa Zuta walked out of her Tel Aviv apartment and took the most emancipating breath of fresh air she’s had since January 1945, when she was liberated from Auschwitz. It was the first time 92-year-old Zuta had left her apartment in three years. While she was fortunate enough to survive years in the Lodz ghetto, where her father and brother died of hunger and disease, followed by Auschwitz, where she watched as the Nazis sent her mother to the gas chamber, she has suffered from various medical ailments ever since. When the British came to liberate the prisoners of Auschwitz, Zuta said, “I didn’t even know my name or where I was from.”

She had arrived in Auschwitz after four years in the Lodz ghetto, after being marched by foot to Bergen-Belsen in the snow with an escort of SS officers and their dogs. “The conditions were like death,” she said.

More than 70 years later, Zuta started to cry as she recounted memories she had tried so long to bury. Recalling her mother walking to the gas chambers, she said, “The sky was red with smoke and I could smell the burning.”

When Zuta left Germany, she could have gone to London, where some of her distant relatives lived. Instead, she chose Israel, where she knew no one. “I wanted to go be with my nation,” she said. She arrived in Tel Aviv in 1947 in poverty. Still, she enlisted in the Hagana, Israel’s pre-state Jewish military, helping her new country win the 1948 war by working with special communications equipment.

Zuta now lives connected to a ventilator. The giant oxygen machine helps her with the lung problems she developed during the Holocaust, but it works only when plugged into electricity. She tried to get a mobile ventilator, but she couldn’t afford the nearly $5,000 price tag, and Israel’s government-run insurance agency refused to subsidize the cost. So, for three years, she was a prisoner in her own home.

***

Since the end of WWII, Germany has paid more than $78.4 billion in reparations and compensation for survivors of Nazi persecution, according to data from the German Finance Ministry. Forty percent of those funds, or about $31 billion, were allocated to Holocaust victims in Israel, where the majority of survivors fled after the war. Yet rather than going solely to individual Holocaust survivors, these funds have been primarily funneled through the Israeli government and the Jewish Claims Conference, an agency founded in 1951 to secure and administer payments to Holocaust victims around the world from Germany. According to the Holocaust Survivors Rights Authority, the Israeli governmental agency entrusted with the issue of Holocaust survivors, there are about 200,000 Holocaust survivors living in Israel, nearly a third of whom live below the poverty line.

Last April, Israel’s welfare minister, Haim Katz, released a scathing report revealing that more than 20,000 survivors in Israel had never received the government assistance owed to them. The undelivered rights and benefits amounted to more than $30 million. Katz’s office is now working to contact these survivors in order to ensure they receive these benefits, which include stipends for nursing care, additional hours for in-home aids, and discounts on electricity.

Katz, a member of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud party, was born in 1945 to two survivors of Auschwitz. Like Rosa Zuta, his family moved to Israel from Germany in 1947. At the press conference where he announced his findings, Katz said, “The numbers clearly show how we’ve all failed—how the bureaucracy, the indifference of officials, and the proliferation of agencies that deal with this issue have produced a situation where survivors go hungry and suffer from cold and neglect.”

In an interview, Katz told me the situation is much worse than those figures depict. After all, he said, his report took into account only those survivors who are still alive today. “If you counted the ones who’ve died and never received aid, it would be much more,” he said, noting that 45 survivors die in Israel every day. “The bureaucracy is so bad that people die before they receive help,” he said.

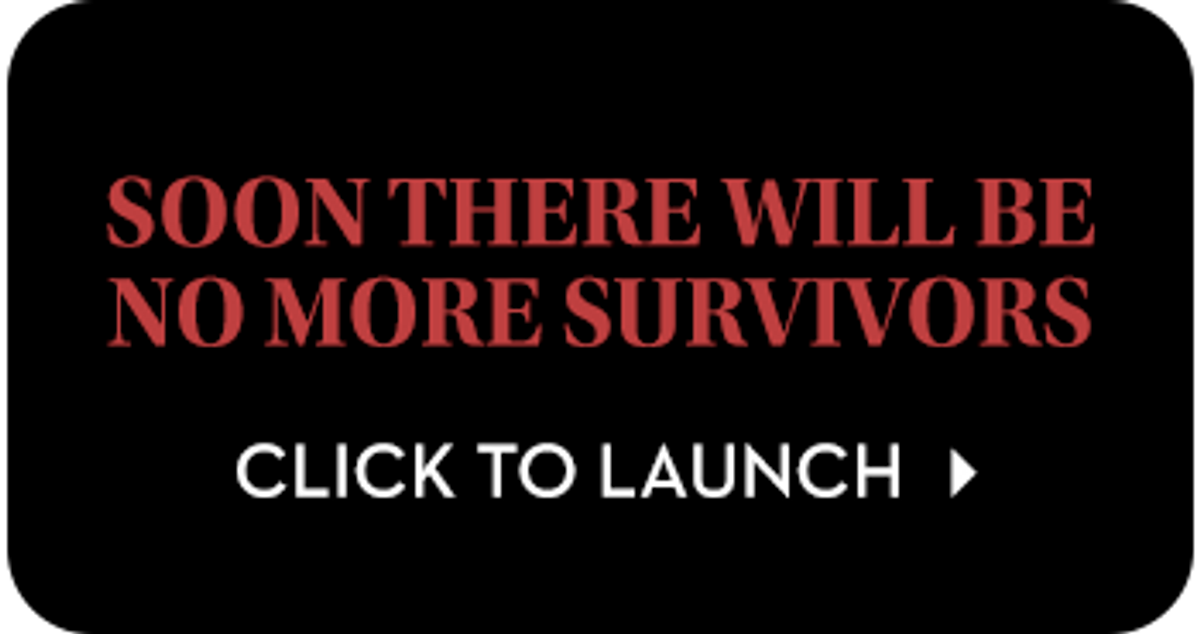

The average age of an Israeli Holocaust survivor today is 87. It’s been estimated that by 2025, all of the remaining survivors will have died. In a testament to how invisible survivors are in Israeli society, and how apathetic the public is to their plight, Katz’s report made absolutely no waves in the Israeli media. It should be news that Holocaust survivors are being left to die in poverty, all while their legacy is used as a justification for the existence of the nation that has so badly neglected them.

For Dora Roth, an 86-year-old survivor, the report was a watershed moment. This was the first time in her life that she’d heard an Israeli official claim any shred of responsibility or remorse on behalf of the government. As one of the most outspoken critics of Israel’s treatment of Holocaust survivors, Roth made headlines in 2013 when she memorably shouted down members of a committee at a hearing in the Israeli parliament.

“Ben-Gurion made a pact, promising we would receive money for the rest of our lives,” Roth demanded, in reference to Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion. “What have you done with the money?” she screamed, pointing her finger at the seemingly unfazed politicians. “Seeing a Holocaust survivor who can’t afford to heat his home in the winter and can’t afford to buy food or medicine is your disgrace. I don’t care about your committees. They mean nothing to us. I came all the way here to ask you one thing: Let us die in dignity.”

Roth was 7 years old when she entered the Warsaw ghetto. She went on to Vilna, and then to the Stutthof concentration camp, where her mother died of hunger and her sister was sent to the gas chamber. She was 15 when the war ended, and she moved to Israel alone. Echoing the accounts of other survivors, Roth said that when she arrived, Israelis treated Holocaust survivors as if what happened to them was somehow their fault. “I heard many times that we went like sheep to the slaughter,” Roth told me. Yet, she continued, the Israeli government was happy to take money from the German government for the suffering she and millions of others endured.

“In my opinion, the government hasn’t helped enough,” said Roth, pointing out the fact that the young state of Israel used this money to build the nation’s hospitals and railway stations. In 1951, when then-Israeli Prime Minister Ben-Gurion and German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer began discussing German reparations for the persecution of the Jewish people, Ben-Gurion demanded the funds go directly to the Israeli government. According to the Luxembourg Agreement, Germany was to aid in the task of “resettling so great a number of uprooted and destitute Jewish refugees.” In 1952, Germany gave Israel $1.5 billion.

“We, the victims of the Holocaust,” said Dora Roth, “should have gotten this money.”

Germany has not provided money directly to the Israeli government since 1952, but rather to the Jewish Claims Conference, the New York-based institution established in 1951 to secure and deliver compensation and reparations from Germany to Holocaust victims around the world. Since 1952, the Claims Conference has received more than $70 billion, which it claims to have paid to more than 800,000 Holocaust victims around the world. According to the organization, it aids more than 130,000 survivors in 47 countries through direct compensation, as well as assistance with home care, food, medicine, health care, transportation, winter relief, legal aid, and socialization.

Dora Roth has spent much of her life advocating for the rights of Holocaust survivors in Israel and traveling the world to share her own experience in the war. When I visited her at her home in northern Israel, she showed me the two bullet wounds on her back from when the Nazis shot the prisoners in her camp as the Russians were coming to liberate them. She weighed 18 kilos—40 pounds—when Russian soldiers found her in a pool of blood and took her to a hospital.

Roth is among the many fortunate survivors who managed, against all odds, to build a more than decent life for themselves in Israel. Her husband was a successful doctor, and together they had two children and five grandchildren. Many others were not as lucky. Some were never able to work or have children because of the mental, emotional and physical tolls the war took on them. These are the men and women who constitute more than half of the remaining survivors living in Israel today, who’ve essentially been left to fend for themselves.

“They should not be living in poverty like this,” Roth tells me. “Germany gave them the money to live the rest of their life comfortably. Where is that money?”

***

Rosa Zuta’s granddaughter is a volunteer at the Association for Immediate Help for Holocaust Survivors (AIHHS), a nonprofit organization based in Tel Aviv that is run by Tamara More, who estimates that she has put nearly $250,000 of her own money into the organization. She receives no government funding, operating solely on private donations and aid from a Swiss charity. Told that she might receive more donations if she had a proper website, More replied, “Holocaust survivors are dying every day. We don’t have time to build a nice website.”

More, the daughter of Holocaust survivors, had a successful career as a business consultant with her own company until 2004, when she decided to devote every waking hour to her organization. She and a group of volunteers had been helping thousands of survivors since 1992, delivering groceries and hot meals, fixing their homes, bringing them to doctor’s appointments, giving them medicine, and even providing a house in which they could live free.

“I didn’t want to register as an association because I knew the moment I did, my life would be over,” More told me in an interview, which took weeks to arrange because of her busy schedule, which consists mostly of answering calls from survivors, and making sure they get what they need. “I tried to postpone it but every year there was a committee to examine the state of Holocaust survivors, and the conclusions of the committee were every year put into a drawer and closed. We saw the survivors we were helping dying one after the other without getting the help they should be getting from the government.”

Asked why she receives no support from the Israeli government or from the Claims Conference, More said she’s been offered this help but refused it. “We don’t want it,” she said, “because we think the money should go directly to the survivors, without anyone getting $50,000 a month as a salary.” She was referring to Gregory Schneider, the head of the Claims Conference, who, according to the organization’s 990 report for 2014, earned $613,000 that year. Avraham Pressler, who represents the Claims Conference in Israel, received a staggering $512,000—a salary that is almost unheard of in Israel outside of the high-tech industry.

More also singled out the Foundation for the Benefit of Holocaust Survivors in Israel, an Israeli organization that receives $105 million annually from the Claims Conference, in addition to millions of dollars from the Israeli government. Several executives of the organization earn more than $150,000 a year—a high salary in Israel, particularly for a nonprofit organization. Despite profits of more than $100 million, in 2012 the organization froze benefits to more than 8,000 Holocaust victims who were eligible for funds.

The day I met More, she was at a shopping center with Efraim, an elderly Holocaust survivor whom AIHHS assists regularly. He had brought with him a gold necklace that once belonged to his late mother, who died in the war. He was trying to sell it to a jeweler because he didn’t have enough money. “This is the only place I can get help,” Efraim said of More’s organization. “Anywhere else I’d have to fill out a hundred forms and maybe when I’m 95 I’d get help.”

Like most of the survivors AIHHS assists, Efraim never had children and no longer has family members to care for him. Some who have children, said More, are estranged from them because of the emotional scars they carried from the Holocaust. “They didn’t know how to treat their children and that’s why their children aren’t there for them now,” she said.

Jewish organizations have no such excuse. A scathing 2006 report released by the New York State Attorney General’s Office revealed gross financial mismanagement by Rabbi Israel Singer, president of the Claims Conference at the time. In 2013, the U.S. Attorney’s Office won a conviction against 10 Claims Conference employees, including a program director, for “the theft of $57 million dollars intended to benefit victims of the Nazi genocide,” committing $57.3 million in fraud. The Claims Conference, for its part, had alerted the FBI in 2009 when it discovered the scheme, in which its own employees had filed fraudulent applications for compensation claims.

The budget for the Holocaust Survivors Rights Authority, the Israeli government agency funded by Israeli taxpayers, was about $1 billion in 2015, representing a major increase from previous years. According to agency director Ofra Ross, 67,000 survivors in Israel receive monthly financial aid and free medical care from the Israeli government. The average monthly payment, she said, is about $700, up from about $500 in 2014. There are 130,000 additional survivors who do not receive monthly financial aid but do receive about $800 a year in free medicine.

Ross, herself the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, admits the government should be doing more but said no amount of money will erase their suffering. “We will never succeed to understand what they went through, and we’ll never succeed to give them enough,” said Ross. “The country is constantly widening the support we provide, so it could be that someday we will be able to help them more. But you can’t return to them what they lost.”

Tamara More has heard these veiled excuses and empty promises for so many years that she grows indignant when discussing them. “This is their money, and no one should be sitting on their money,” she said, the tone of her voice rising several octaves as she begins to release her frustration. “There are so many people living off the money of Holocaust survivors, while many survivors don’t have money to eat, or to take a taxi to wherever they want, and they have to travel by bus at the age of 90. They can hardly walk, and they don’t have money for someone to take care of them, help them eat, or dress, or have a shower. These survivors should get the money now. Not in bits and pieces while the organization is paying itself hundreds of millions from the survivors’ money.”

***

To read about the struggles of many Holocaust survivors in America, click here.

Yardena Schwartz is an award-winning freelance journalist and Emmy-nominated producer. Her reporting has been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Time, The New York Review of Books, and The Economist, among other publications. She is writing a book about the 1929 Hebron massacre and its reverberations today, under contract with Union Square & Co., a subsidiary of Barnes & Noble.