Israel’s New Post-Netanyahu Government, Explained

Six essential insights about what just happened in Israel and what it means for the country’s future

UPDATE, 6/13, 1:55pm: The new Israeli government was successfully voted in, and this article has been lightly revised accordingly. Read about the implications below.

After much last-minute drama, Israel has a new government without Benjamin Netanyahu at its head for the first time in 12 years. But what will it look like? And what does it mean for Israel and the world? There has been a lot of fervent speculation on these points, often from people with agendas or poor records on prognostication on Israeli politics. Let’s sort out the signal from the noise.

1. The basics: The reason Israel has had four elections in the past two years is that the country has an anti-Netanyahu majority, but the anti-Netanyahu parties cannot agree on anything other than Netanyahu. As a result, while Netanyahu has repeatedly been unable to form a government, his opponents have been unable to overcome their differences and replace him, leaving him in power. That is, until last night. At literally the 11th hour, opposition leader Yair Lapid managed to solve the Rubik’s Cube of Israeli politics and broker an unprecedented coalition of settlers, Arabs, leftists, rightists and moderates:

If Netanyahu’s pressure campaign fails to fracture this alliance in the coming days, it will replace him.

2. This is Yair Lapid’s coalition, everyone else is just living in it. In order to sell a unity government to right-wing voters that would depose Israel’s longest-serving right-wing prime minister, the coalition needed a right-wing frontman. That man is Naftali Bennett, former Netanyahu protégé, settler leader, and head of the nationalist Yamina party. To bring him on board, Lapid offered to let Bennett go first in a prime ministerial rotation, even though Bennett got just 7 Knesset seats to Lapid’s 17. As a result, for the first two years, Bennett will be the face of the government before Lapid takes over.

But the power behind the throne will be someone else entirely. The coalition was negotiated by Lapid and will have a majority of ministers from the center and left, in deference to their greater numbers. And the government will rely on the votes of an Arab party for its continued existence. In other words, Lapid outfitted Bennett in a golden straitjacket—giving him the trappings of power without the ability to fully exercise it. Bennett is an avowed religious nationalist who advocates the annexation of the West Bank. But he cannot pass his own program in this government, as he himself has acknowledged.

Bennett took this deal because it was his only chance to be prime minister, and because it was his least-bad option. Many forget, but the first iteration of Bennett’s party did not even make the Knesset in the first of Israel’s four elections over the past two years. With the rise of extremist alternatives to his right, and the stigma of having been willing to negotiate with the left, Bennett had ample reason to fear that if he didn’t take this deal, he might not even be in the next parliament—and Lapid took advantage.

Which is why the undeniable winner here is Lapid. It was Lapid who ran the opposition electoral strategy that gave it the numbers to oust Netanyahu. It was Lapid who succeeded where others had failed and personally persuaded the disparate anti-Bibi factions to unite under one banner. And it was Lapid who spent these past two years building relationships with Israel’s Arab parties, resulting in the first-ever independent Arab party—the Islamist Ra’am—joining his coalition.

A secular liberal who founded the left-right fusionist party Yesh Atid in 2012, Lapid has been perennially underestimated in both Israeli politics and the international media, which is why many of you have probably never heard of him, despite his party’s repeatedly getting more votes than any other aside from Netanyahu’s. But when this government takes office, he will have accomplished one of the most remarkable feats in Israeli politics and solidified himself as the leader of the Israeli center and left.

3. This is a watershed moment for Arab participation in Israeli politics. Israel’s parliament has 120 seats, which means that a coalition needs 61 to govern. This new coalition has exactly 61 seats, and four of those seats belong to Ra’am, or the United Arab List, under the leadership of MK Mansour Abbas. A conservative religious pragmatist, Abbas promised his voters that he would break the taboo on cooperation with Zionist Israeli parties and deliver results for his constituents—and now he is poised to become the most powerful Arab politician in Israeli history. In recent weeks, Abbas already nabbed top committee posts from Lapid in exchange for coordinating to block Netanyahu’s maneuvers in parliament. Now, as Ra’am becomes the first Arab party to enter an Israeli coalition—where it will hold decisive votes—Abbas and his voters stand to gain more, as media reports indicate he secured major policy victories for Israel’s Arab sector in return for his cooperation.

This matters not just for Abbas and not just for this election. It could impact the entire future of Israeli electoral politics, for two reasons. First, by breaking the taboo against Jewish-Arab political cooperation, Abbas and Lapid have opened up entire new parliamentary alignments; adding Arab parties to a left or centrist alliance makes it far more competitive against the right. This is precisely why the Israeli right’s most racist politicians were so vehemently opposed to Netanyahu’s own earlier attempt to partner with Abbas in his (failed) effort to form a government, and torpedoed his attempt to normalize Arabs as coalition partners. “The Arabs’ joining up with the Jewish left will bring decades of left-wing rule,” warned Bezalel Smotrich of the neo-Kahanist party.

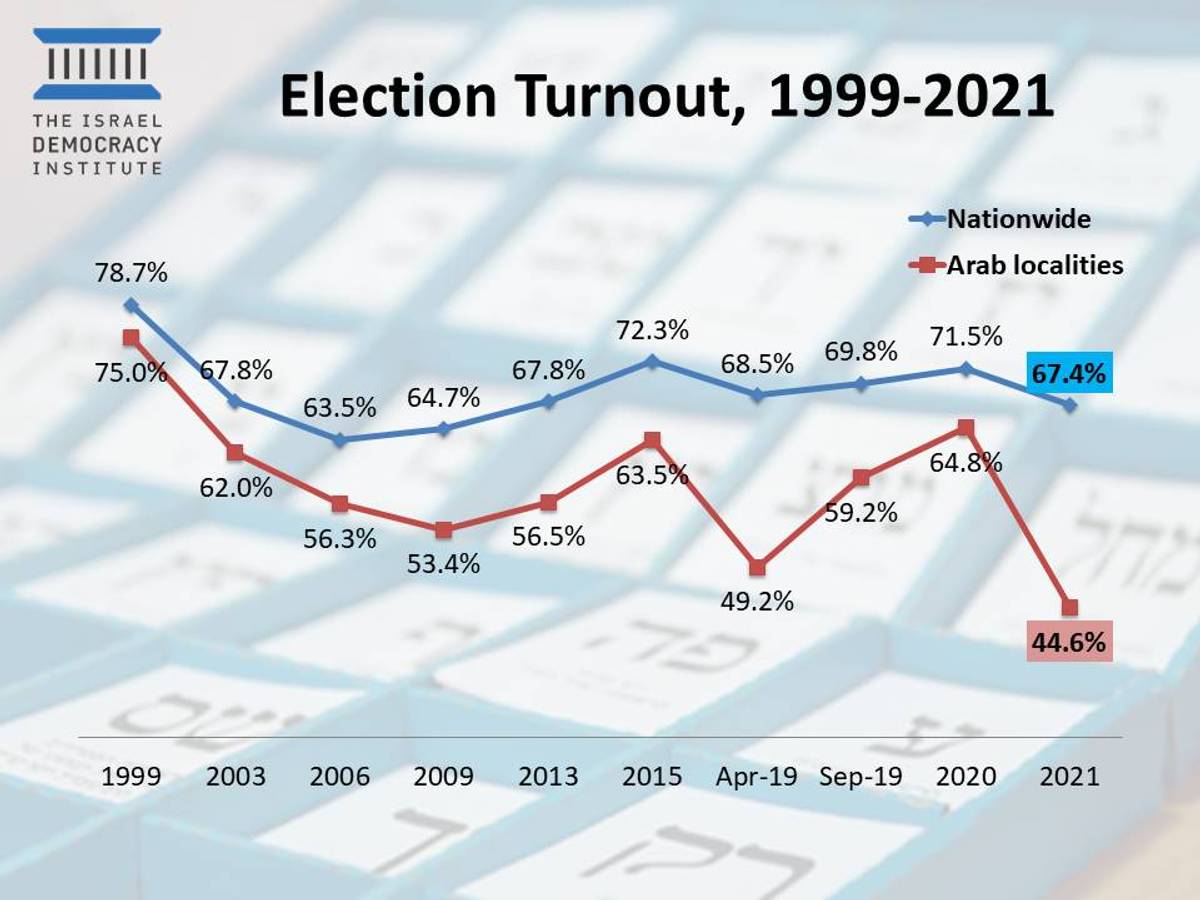

The second reason this matters is even more consequential: If an Arab politician like Abbas can deliver real world results for his Palestinian constituents, demonstrating the ability of Arab voters to affect major change, the community might start to turn out in greater numbers. For decades, Arab voter turnout has lagged the overall turnout in Israel. But if those voters started flocking to the polls in more comparable numbers to the general Jewish population, it would add multiple new Knesset seats and dramatically erode the right’s ability to win elections.

During his campaign, Lapid talked openly and explicitly about the Israeli state’s failure to serve its Arab citizens. For his nascent political alliance to take the next step, he’ll need to walk the walk now, too.

4. This is not a left-wing government, but it is a shift to the left. No government with Naftali Bennett at its head, however hobbled, can plausibly be deemed left wing. But replacing Benjamin Netanyahu and his extremist ministers with leftists, centrists, and Arabs is undeniably a progressive shift.

To put it very roughly, it’s like replacing Donald Trump with Liz Cheney, but if Cheney couldn’t pass anything without the assent of Bernie Sanders, Nancy Pelosi, Ilhan Omar, and Mitt Romney, and if she would later get replaced with Chuck Schumer. This is not necessarily a recipe for effective governance, but it’s also nothing like a right-wing government. People claiming there is no difference between this government and Netanyahu’s either don’t understand how parliamentary democracy works, or are ideologically invested in painting all Israeli parties from left to right with the same irredeemable brush. Any progressive who looks at the first government without Netanyahu in over a decade, and the first with an Arab party in decades, and does not see progress does not want to see progress—and risks missing an opportunity for greater progress.

5. Can it last? As noted above, this proposed coalition sits on a knife’s edge, with just 61 out of 120 seats. Even if it actually gets sworn in, between its numbers and its incoherent mix of internal ideologies, it’s easy to see how this government could fall apart under the weight of its own contradictions. At the same time, the coalition’s members have many political incentives to stick together. Bennett and his party know that they will be punished by right-wing voters if they do not deliver while in government. The same is true for Abbas, who must make good on his promises to his Arab constituents. Lapid and his allies want the government to last two years so that he will get his turn at the helm. And all the while, Benjamin Netanyahu will loom over it all as leader of the opposition, providing a constant reminder to the coalition as to why they banded together in the first place. Netanyahu himself managed to hold power for years with a 61-seat coalition, which means it’s entirely possible for his opponents to do the same, and more likely than many skeptics assume. But it won’t be easy.

6. Biden’s big opportunity: Netanyahu, with his American upbringing and unaccented English, long believed that he could run circles around American politics and politicians—and often did. This mindset led Bibi to take unprecedented partisan stances in American politics, ratchet up public tensions with President Barack Obama, openly campaign against the Iran deal in the U.S. Congress, and regularly rebuff entreaties on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

But historically, most Israeli leaders—including avowedly right-wing ones like Ariel Sharon—have not had the appetite for such confrontation, and responded to pressure from the senior partner in the U.S.-Israel relationship. Bennett, especially in this government, may find it hard to shrug off Biden’s interventions on everything from Iran to Palestinian policy in the way Netanyahu has with successive American presidents. And Lapid, the other half of this government, wants nothing more than to work closely with Biden and the Democrats to reset the U.S.-Israel relationship on a bipartisan footing. This means that a pathway for a sophisticated and serious diplomatic approach on Israel, the West Bank, Gaza, and the Iran deal just opened up where there wasn’t one yesterday. The question is whether the administration is ready to seize it.

Donald Trump, contrary to some of his critics, was quite successful in remaking much of the Middle East in his image. From his empowering of like-minded right-wing elements in Israel to his brokering of the Abraham Accords, Trump showed that American presidents have far more diplomatic ability to affect the trajectory in Israel and the region than is often assumed. That’s one lesson that Biden might learn for his own purposes.

Yair Rosenberg is a senior writer at Tablet. Subscribe to his newsletter, listen to his music, and follow him on Twitter and Facebook.